Jakob Sellaoui’s “Uncomfortable Pavilion,” 2022, pays homage to the Schindler House. (Carolina A. Miranda / Los Angeles Times)

The history of Rudolph Schindler’s 1922 house is a quintessential Los Angeles story: a story of new ideas that are rapidly devised and rapidly dismissed, only to reemerge years later as pioneering and influential.

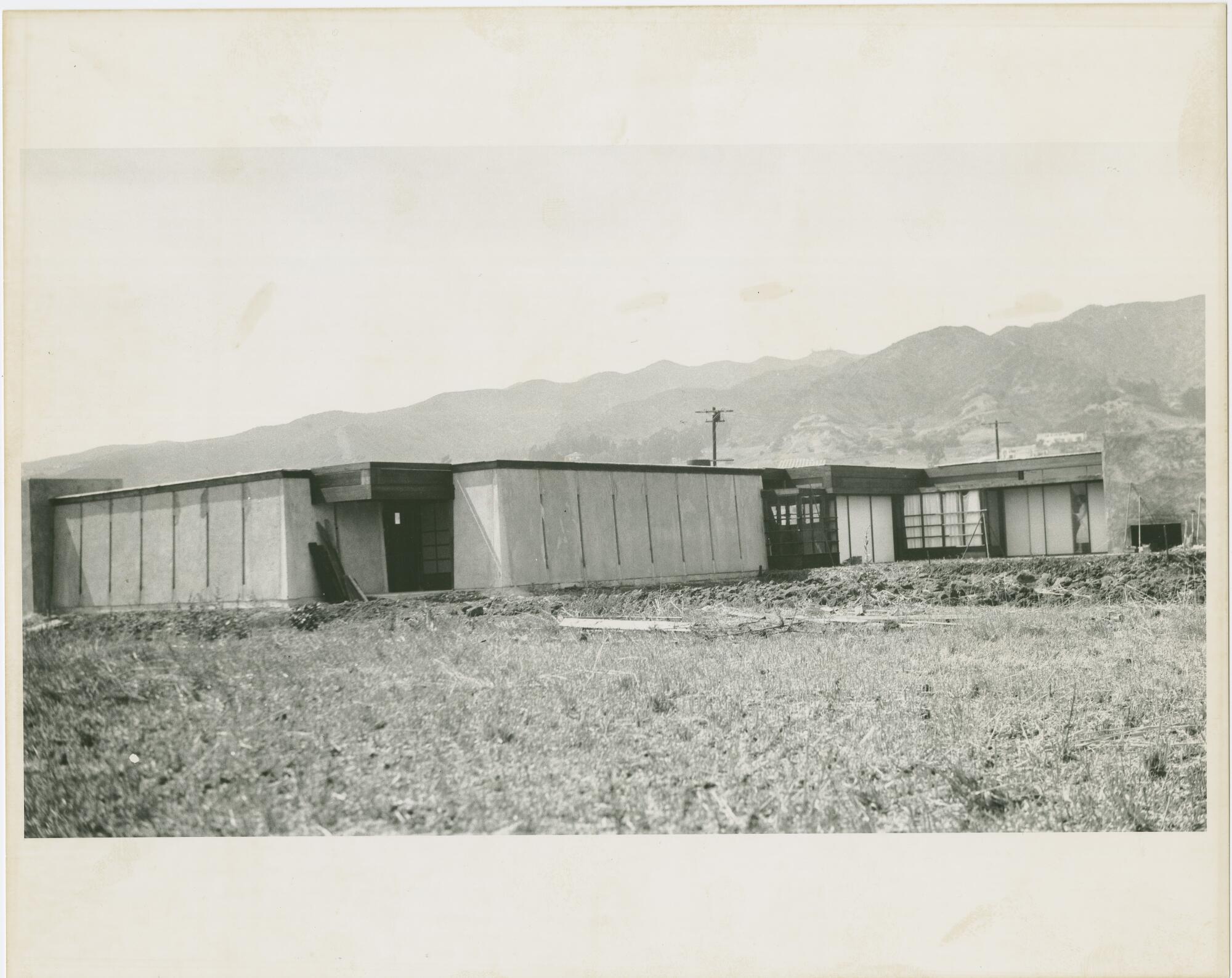

Built on an empty lot at 835 N. Kings Road in West Hollywood, then a scrubby unincorporated suburb of L.A., the Schindler House was indoor-outdoor and open plan decades before these were a thing — an intersecting sequence of multipurpose “studiorooms” that spilled into courtyards via sliding doors. The very DIY affair consisted of tilt-up concrete panels that two men could put into place with rope and a hoist. In fact, Schindler and his friend, engineer Clyde Chace, did some of the work themselves. Then, they and their wives, Pauline Gibling Schindler and Marian Chace, respectively, moved in.

The home’s innovative attributes — its rough-hewn aesthetic and attention to space — earned Schindler the admiration of fellow architects and a clutch of adventurous patrons, but it was generally ignored by the U.S. architectural establishment. For decades, the house was more cult hit than fan favorite. “Schindler is an architect’s architect,” Los Angeles critic Esther McCoy wrote in 1945.

For a time, it seemed he was destined to remain just that. When Schindler died in 1953, his (very brief) obituary in The Times made mention of the mechanical-looking beach house he’d built for wellness guru Philip Lovell in Newport Beach — but not the avant-garde home he had designed for himself.

A century later, the story has come full circle.

As David Gebhard and Robert Winter wrote of the Schindler House in the 2018 edition of “An Architectural Guidebook to Los Angeles,” “It is a classic in Modern architecture, and we use the word sparingly.”

Evoking elements of traditional Japanese design and Viennese Modernism (Schindler was born in Austria), the home — with its flat roof and sliding doors — helped point the way for domestic architecture in the United States.

Marking its centenary is a new exhibition organized by the MAK Center for Art and Architecture that features an array of public programs, including lectures, performances, audio tours, “edible” poetry and even an opera. Curated by MAK Center Director Jia Yi Gu, Gary Riichirō Fox of the Getty Research Institute and historian Sarah Hearne, “Schindler House: 100 Years in the Making” brings together, within Schindler’s home, art, artifacts and objects that speak to its legacy.

In the 1920s, when West Hollywood was an expanse of bean fields stretching between oil derricks to the south and the hills to the north, the area became a haven to an eclectic group of artists, poets and architects.

This is not an exhaustive historical survey. (For that, it’s best to locate the informative catalog for “The Architecture of R.M. Schindler,” a thorough review of Schindler’s work displayed at the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles in 2001.) The MAK show serves more as a meditation on several themes, including L.A. in the early 20th century, the home’s role as a gathering site and the way it has evolved over the years.

The exhibition follows another recent Schindler House-inspired show, “835 Kings Road,” curated by Silvia Perea at the Art, Design & Architecture Museum at UC Santa Barbara (which holds Schindler’s papers). That exhibition, which concluded in May, featured a fictional installation by artist Mona Kuhn, with a soundtrack by Boris Salchow, inspired by Schindler’s romantic life and the home’s bohemian vibe.

In its day, Schindler’s house was indeed the happening spot for L.A.’s radical set.

Much of this was thanks to Pauline, a composer and writer who used the house as a stage. There were salons, poetry recitals and dances — at least one of which, to the horror of neighbors, transpired in the nude. After the Chaces relocated to Florida in 1924, their studios were occupied by figures such as composer John Cage and collector Galka Scheyer. When fellow Austrian architect Richard Neutra moved to Los Angeles in the 1920s, his first home was the Schindler House.

Famously — or rather infamously — Schindler and Neutra were friends and collaborators until their relationship was ruptured by conflict over a commission, a years-long schism that came to an end in 1953 when the two, purely coincidentally, ended up sharing a hospital room. Neutra was recovering from a heart attack, and Schindler was being treated for the cancer that would claim his life that year.

He was 65 when he died, an age at which many architects are just getting started.

An Esther McCoy revival tells story of L.A.’s modern architecture

“Schindler House: 100 Years in the Making” opens with a large-scale reproduction of a manuscript page by McCoy that details aspects of the home’s restoration in the 1980s under the auspices of the Friends of the Schindler House, a not-for-profit group that took on the property after Pauline’s death in 1977. (Currently, the house is owned by the Friends but its programming is overseen by the MAK Center.)

McCoy, who had worked in Schindler’s studio, was key to preserving his legacy — covering his work in numerous dispatches and including him in her influential 1960 book, “Five California Architects.” Her manuscript page speaks to the ways a structure, along with its meanings, can evolve. Over its history, the Schindler House saw spaces renovated, canvas-lined doors replaced with glass and some of its walls painted pink.

Yes ... pink.

This rather infamous act of redecoration came courtesy of Pauline after she and Rudolph had split but continued to share the house.

An installation by artist Stephen Prina in the exhibition nods to this story. It consists of a shelving structure, painted a radiant pink, that emerges at a prominent angle from a corner of the studio once inhabited by Pauline. Prina originally created the piece as part of a large 2011 installation at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art that featured numerous re-creations of Schindler-designed objects painted in the same pink.

Architecture, it turns out, is never a static thing.

Review: History lurks in Stephen Prina’s sculptures at LACMA

It can be easy to wax romantic about Schindler and the ideas and artists that inspired his namesake house. He was a Viennese Modernist enamored with the allure of the Americas, where he arrived in 1914 and quickly absorbed his adoptive country’s wide-open spaces and homegrown traditions.

Schindler worked in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Chicago office before relocating to Los Angeles, where he oversaw construction of Wright’s hilltop home for heiress Aline Barnsdall (now known as the Hollyhock House). On the drive west, he made a formative detour to Indigenous pueblos around Taos, N.M., which he later described as “the only buildings [in America] which testify to the deep feeling for soil on which they stand.”

These influences are mildly evident at the Schindler House, with its concrete slab walls that gently taper at the top, evoking the tilting contours of Indigenous adobes. (The show includes photographic images taken by Schindler during his sojourn in New Mexico.)

Schindler was influenced by Wright, but he hardly treated his ideas as gospel. Where Wright was formal and rigid, Schindler was anything but — both in his designs and in his person. In photos, he is often decked out in ensembles that evoke the look of a dapper Spanish peasant: white trousers, white shirt with splayed collar and hair coiffed into a snappy pompadour.

An even more direct inspiration was a camping trip to Yosemite: The home’s design includes outdoor sleeping porches on the second story, dubbed “sleeping baskets,” that were topped only by a sheet of canvas.

These structures are beautifully evoked in an ethereal courtyard pavilion — a structure of wood and billowing gauze — that was created for the exhibition by Austrian architect Jakob Sellaoui.

MAK’s exhibition smartly recasts some of these dreamy accounts, which elide some of L.A.’s uglier historical episodes.

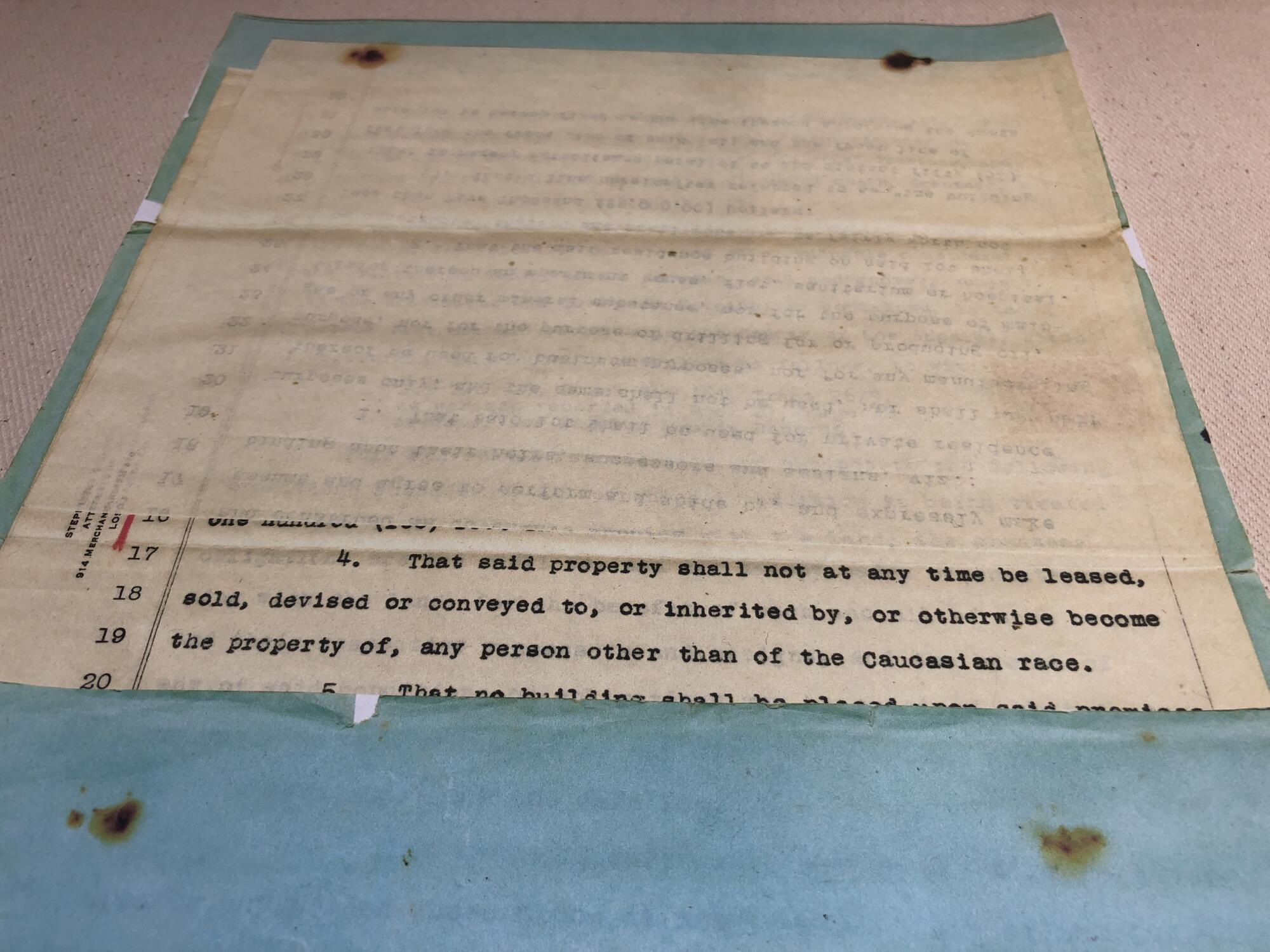

The land on which the Schindler House sits was acquired in part from a judge and real estate developer who had served in the Confederate cavalry during the Civil War and regularly hosted events for the United Daughters of the Confederacy. When the plot was sold to Schindler, the deed included a covenant that prohibited the property from being “leased, sold, devised or conveyed to, or inherited by, or otherwise becoming the property of, any person other than of the Caucasian race.”

That deed and other enlightening historical documents have been re-created by artist Kathi Hofer and displayed on the walls and in vitrines around the house.

Along with related artworks, these help rewrite the narrative around the European Modernists working in Southern California — that L.A. offered them freedom and oodles of empty space in which to work out their ideas.

The space was never empty. It was, in fact, very fraught.

The exhibition is an opportunity to consider the forces that shaped the Schindler House. It’s also a chance to revel in the home’s aesthetic pleasures. One of the more beguiling installations is a luminous architectonic piece by Andrea Lenardin Madden inspired by the home’s slender vertical windows; it gives the illusion she has added additional windows to the space.

The centennial also marks a moment to consider the home itself.

The house is showing its age, with cracks running through floors and woodwork that is decaying. (Friends of the Schindler House has launched a $1-million campaign to get repairs done, of which it has raised about $100,000.)

Despite the wrinkles, Schindler’s concept remains relevant — something to draw from as L.A. finds itself in a housing crunch.

The house was conceived as a multifamily dwelling, designed so that the Schindlers could occupy a pair of studios on the southern side of the house while those on the north were turned over to the Chaces (and their successors). Between the studios lay a kitchen and a guest apartment.

The idea was that each individual — male and female — would have space in which to live and work and that the kitchen would be shared. It’s what we today would refer to as co-housing. It was also remarkably gender-egalitarian for the era.

Ultimately, the Schindler House is deeply of its place.

“I came to live and work in California,” Schindler wrote in the year before his death. “I camped under the open sky, in the redwoods, on the beach, the foothills, and the desert. I tested its adobe, its granite, and its sky. And out of a carefully built up conception of how the human being could grow roots in this soil — unique and delightful — I built my house. And unless I failed it should be as Californian as the Parthenon is Greek and the Forum Roman.”

It could exist nowhere but California. “Schindler House: 100 Years in the Making” is a thoughtful way to get reacquainted with the icon that quietly resides in our midst.

'Schindler House: 100 Years in the Making'

Where: Schindler House, 835 N. Kings Road, West Hollywood

When: Through Sept. 25

Info: makcenter.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.