Real estate, transit, oil — how early L.A. built fortunes and bred scoundrels

Sometimes, history cold-bloodedly decrees that the difference between a crackpot and a genius comes down to the size of the bank account he winds up with. Sometimes, history gets it wrong.

Over the space of a few decades, Silicon Valley has staged its own Wilder West show, with a cast of nerdy outliers who, with both BS and brilliance, have conjured up and talked up some completely absurd notions, some unnerving ones, and, once in a while, some world-altering ideas that can bear comparison to Thomas Edison’s.

Tech fortunes can arise from spectacular failures and uneasy successes, and lately Elon Musk looks like a man who’s been doing both.

The mantra “move fast and break things” is original to Facebook, but the idea is hardly original. The vast plain of Los Angeles has had a census book’s worth of high-reward, high-risk chance-takers, visionaries and flimflammers, all plowing their renegade furrows in the land that was never theirs for the taking. But they took it anyway — and manipulated it to their will.

You already know about the pantheon of movie moguls who rose from the grubbiest of jobs — scrap collector, glove maker, soap seller — to earn more money and wield more of a certain kind of power than any American president.

You have heard, too, of the early masters of the universe of Southern California, the amassers of real estate, which was the same as power — the Huntingtons, Collis and Henry, uncle and nephew, enriched by land and commerce and transportation, and the Otis-Chandler family, dictating the rule book for the emerging L.A., directing its future into oil and aviation, and making sure that on terra firma, they and their partners, still-familiar names like Moses Sherman, the two Isaacs, Van Nuys and Lankershim, owned a beefy piece of the San Fernando Valley when civic machinations brought Owens Valley water to it.

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Even among the legions of Angelenos with a genius for real estate, Harry Culver stood out. He put little skin of his own in his first development, but he helped to persuade others to invest. As California historian Kevin Starr wrote, Culver used gimmicks and giveaways and stunts like kids’ boxcar races, raffles, parades, and, memorably, a polo game played from the running boards of Model Ts.

His genius was in insisting that his salesmen pitch buyers with the upwardly mobile notion of “home” — secure, solid, safe. Taking families out of the “dust, dirt, and smoke” of a city apartment and putting them into houses in a “fresh, pure, health-giving district” was a rise in class and station all by itself. That’s one reason Culver sold some houses complete with pictures, furniture and Victrola, lest families’ unfamiliarity with their new status betray their striving origins.

Much of his sales pitch language, like everything else at the time, was racially coded. Streetsblog LA found that in 1927, Culver approved this message: “The Los Angeles Realty Board recommends that Realtors should not sell property to other than Caucasian in territories occupied by them. Deed and Covenant Restrictions probably are the only way that the matter can be controlled; and Realty Boards should be interested. This is the general opinion of all boards in the state.”

Sharp tactics and hard sells had some salesmen using the slickest of tricks. On empty lots of unlikely desirability, they posted “SOLD” signs or dropped bricks and lumber to give the impression of industry and demand. In the real estate boom of the 1880s, there were stories — with truth at the bottom of some of them — of salesmen sticking oranges on the spikes of Joshua trees to sell high-desert land as fecund for citrus groves. Land was sold without any clear title, to eager buyers who didn’t bother to ask. Land in the bed of the L.A. River was bought readily — and some of it is still in private hands.

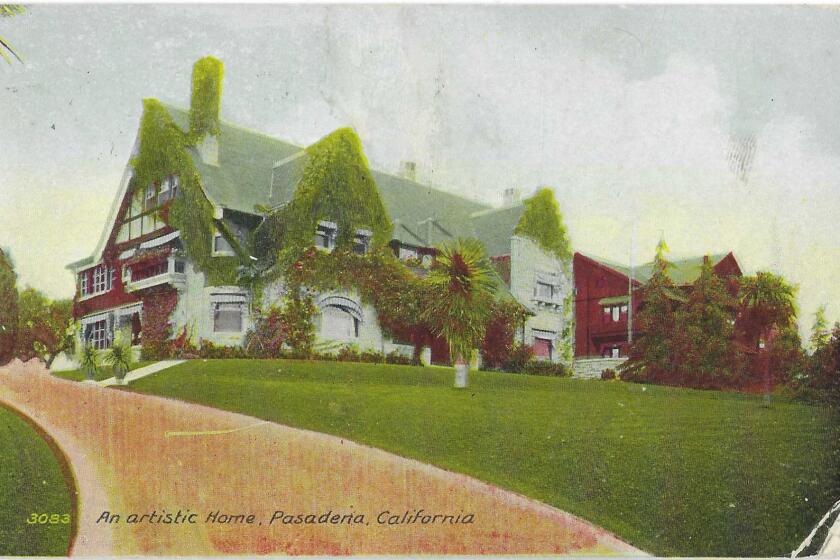

L.A.’s public beauty spots deserve a visit, by all means. But it’s the houses that surprise visitors and gratify us, even if they can only be glimpsed from a sidewalk.

Simon Homburg — whose name is so tantalizingly close to “humbug” — became what even a routine 1944 government document on rural land use was emboldened to call “one of the most unprincipled land speculators” of the 1880s.

Homburg bought two big chunks of federal land — that part was legit, at least — and started his sales spiel. The land was in the mountains in eastern L.A. County, so steep that even mountain goats might have a hard time climbing it.

He cut each acre into 12 or 14 lots, and each lot cost him about 10 cents. He flipped them to credulous buyers for as much as $250 each. He sensibly didn’t advertise here, where people might actually know the terrain, but in the East and in Europe, whence no one could eyeball the merchandise. He made himself about $50,000. He headed north in 1888 and tried a slightly different scam in Washington state, where he was caught and shipped south to San Francisco to be tried for conspiracy.

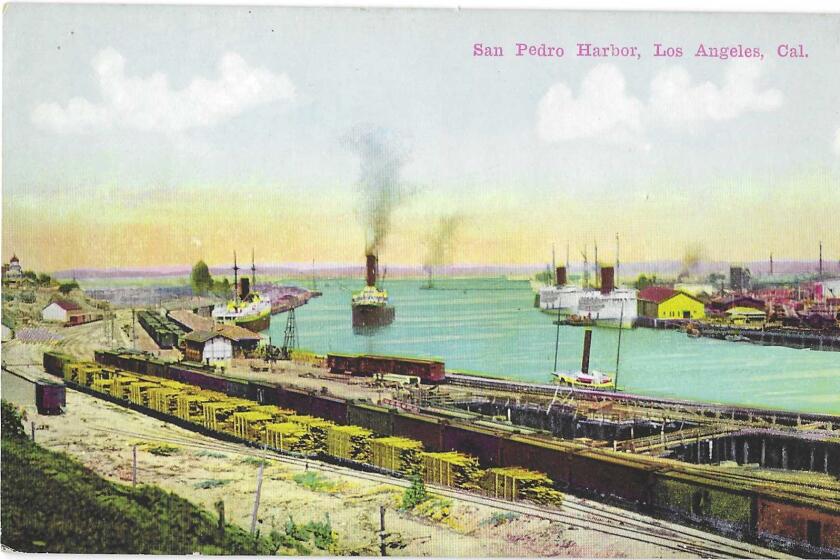

There were plenty of big-thinking and big-acting characters; Phineas Banning was a move-fast-and-break-things guy when there was nothing to break except the public’s determination to say “nope, can’t be done.”

He blew into town in 1851, one year after statehood, and over the next 30 years, he managed to do good and do well, creating the foundations of modern L.A. transportation, connecting the central pueblo to the rudimentary port in San Pedro.

When you think about it, it doesn’t make much sense for 1890s L.A. to put its port all the way in San Pedro. This is the story of how that came to be — and not the competing alternative, Santa Monica.

He was 20 years old. By the time he was 21, he had set up a wagon and coach business moving freight and passengers between San Pedro and what was then downtown L.A. It may not sound like much now, when we have freeways and Metrolink and ride-sharing, but it was an enormous thing for Angelenos to see, and they turned out to watch horsemen race the carriages, and eventually the train, into town.

In time, Banning would help to persuade Southern Pacific to make the critical decision to bring its lines to Los Angeles. He also talked Angelenos into endorsing a bond issue to build a railroad on the downtown-to-harbor route; it passed by 39 votes.

There was no mistaking who he was, and almost everyone in town recognized him on sight. Everything about him — from his voice to his belly to his ambition — was big. He disdained neckties, wore flamboyant galluses and too-short pants. When his brother-in-law was murdered, he tried to shoot the killer in court but was held back by his friends. Undeterred, he led some vigilantes a few days later to seize the man and hang him from a gate.

He made and spent money with equal gusto. His house — which, mirabile dictu, still stands, as a museum, in Wilmington — was generous in its hospitality. During the Civil War, Union officers could be sure of a Champagne welcome. When Banning was given the California militia title of brigadier general — to a regiment that existed only on paper — he could be forgiven for insisting on people calling him “General” ever after.

Banning’s was a practical vision for a city that he left a very different one from the one he found when he arrived.

Then there are the men who pursue more fanciful chimeras, the imagi-makers whose visions helped to give L.A. its reputation as a place where quirky notions can find fertile purchase.

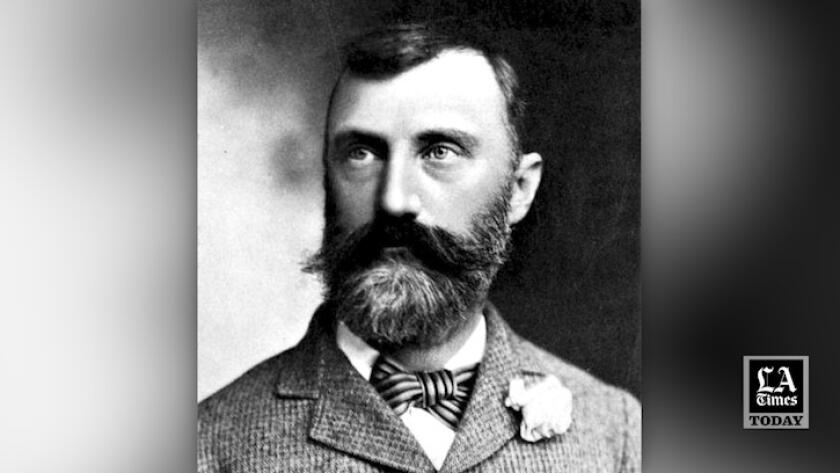

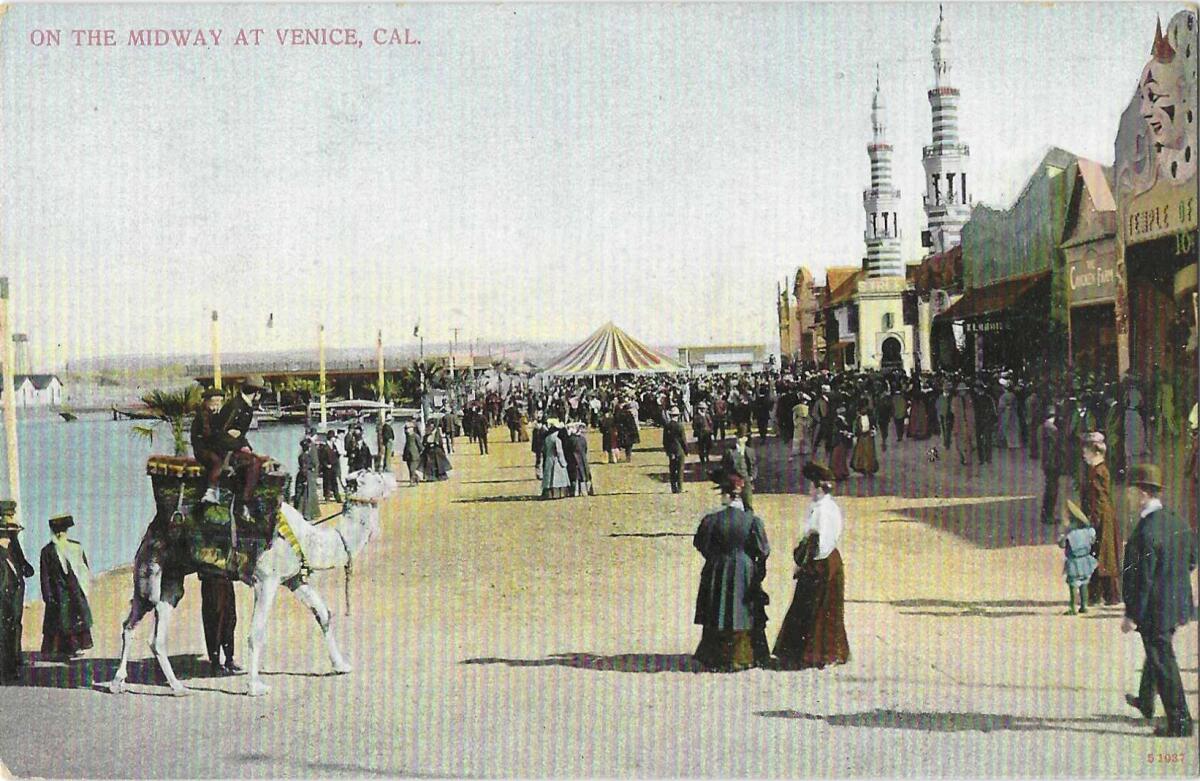

Venice, the carnivalery seaside neighborhood of L.A., you know; its father, Abbot Kinney, perhaps not so much.

He took the fortune he made from selling millions of Sweet Caporal cigarettes and came here in 1880, first creating the Ocean Park neighborhood, an everyman paradise with golf, tennis, a country club — an early version of today’s golf-course homes. And then he spent another fortune to build Venice of America, using the coastal marshland to re-create an Italian Venice. It opened July 4, 1905, and it’s a delight to imagine: arcades for strolling, canals with arched bridges, gondolas and gondoliers. A visitor from Salt Lake City that year couldn’t say enough about the beauty of the place, and about the meal at the Cabrillo Ship hotel — chicken and eggs from Venice gardens, milk and butter from Venice cows.

Kinney intended that Venice of America would be the nation’s aesthetic renaissance, copied far and wide. “I have always had a dream of building an ideal city which should be partly for study, partly for recreation, and partly for health. … I never had any idea of making this a resort for rich people. The devil can attend to the rich without assistance.”

Eventually, though, the canals were filled in, the amusement attractions waxed and waned, the housing fell into decrepitude or got plowed under for bigger and better. Venice in some ways became a place for rich people.

Kinney turned his formidable impulses elsewhere. He campaigned with an expert’s knowledge for modern forestry techniques, to the benefit of the nation’s parks, especially Yosemite, and to building free public library systems in some L.A. County towns. (At the time it was no real discredit to him — many other Americans of wealth and renown felt the same way — but it certainly is in retrospect, that he argued against Asian immigration because he thought the influx “degraded” labor, and hoped for “a legal obligation on every superior woman to breed.” I think we all have an inkling what he meant by “superior.”)

When a Times man asked him in 1907 why he hadn’t named his dream city for himself, he ruminated. “There were some pharaohs in Egypt who spent their lives building pyramids that would serve to perpetuate their memories forever. And people even forgot how to read the language in which their achievements were written. What do you think the chances are for my being remembered?” Abbot Kinney Boulevard lies inland from Venice Beach; how many people think it’s named for some kind of religious friar?

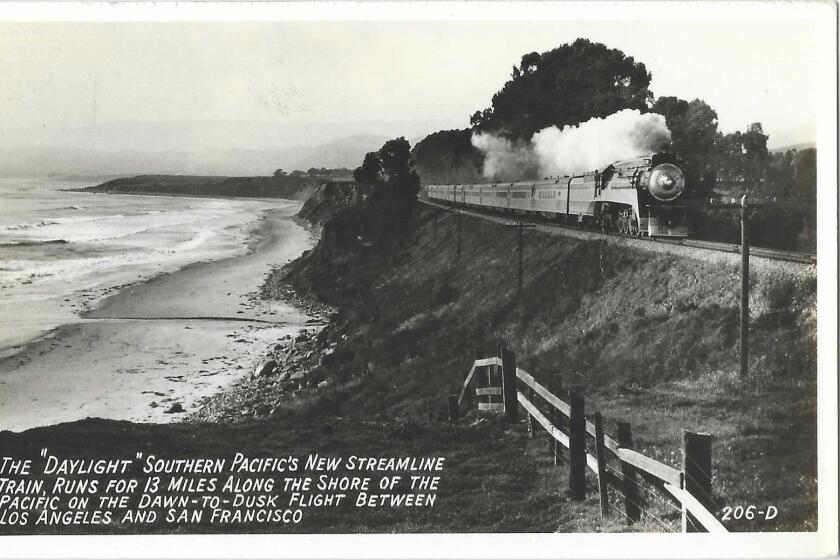

The beauty of train trips used to be a key selling point. But with the Pacific Surfliner suffering the effects of climate change, safety and reliability may trump the pretty view.

The one among these men I would most have like to have met was Thaddeus Lowe, to hear him tell his stories.

He claimed to have been the most shot-at man in the Civil War. How? Because he persuaded President Lincoln of the usefulness of aerial balloons for wartime surveillance, and he did it, as the story goes, by sending Lincoln a telegram from a hot-air balloon 500 feet above the White House: “This point of observation commands an area nearly fifty miles in diameter … I have the pleasure in sending you this first dispatch ever telegraphed from an aerial station …”

Never let it be said that Lowe was timid. Lincoln admired the idea, the Union Army Balloon Corps became a thing, and Lowe made about 3,000 sorties to survey the Confederate enemy’s positions.

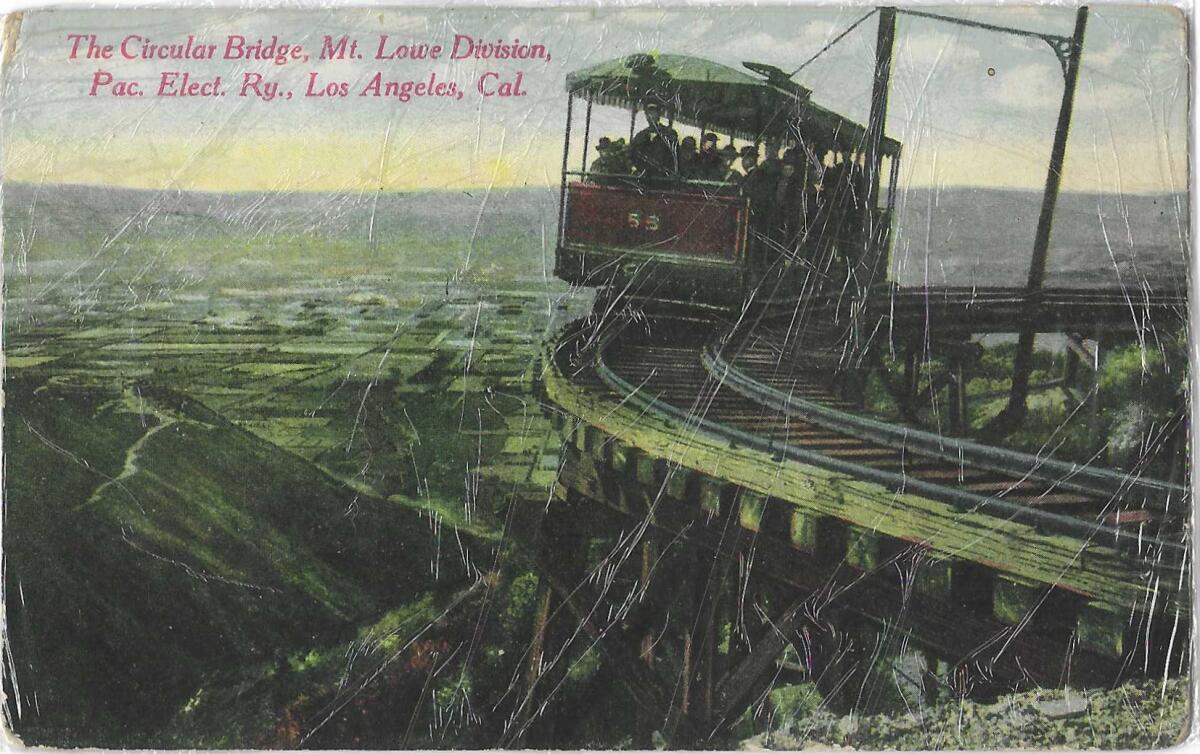

In time, Lowe made a fortune making ice more efficiently, which revolutionized how and what Americans ate, and presently, Lowe made his way west, as such men often did in those years, to Pasadena, to spend his fortune on his monumental new dream: a scenic mountain railway up to the corrugated slopes of Oak Mountain — later renamed Mt. Lowe — and Echo Mountain, where he would build an observatory.

The Mt. Lowe narrow-gauge electrical railway was a singular success, hoisting Angelenos from the valley in Altadena, up more than 3,000 feet over something more than a half-dozen miles of hair-raising hairpin curves to cool forests and a resort hotel with a bowling alley, stables, waterfall trails, tennis, and, soon, a rustic alpine tavern serving ye olde fare like baked beans, cornbread and turkey.

“Professor” Lowe’s observatory opened its eye to the skies 10 years before the Mt. Wilson observatory did the same on a nearby peak. Lowe’s survived until it was blown to bits in the late 1920s. In fact, what doomed Lowe’s brilliant, eccentric vertical, rustic Disneyland was the national Panic of 1893, the enormous costs of running the operation, Lowe’s own financial reverses, and then, before and after Lowe had lost control, the forces of nature: fires and floods.

In 1910, three years before he died, Lowe — still an ardent believer in manned flight — went to the groundbreaking Los Angeles air show in Dominguez Hills. He took along with him his 8-year-old granddaughter; you might know her as Pancho Barnes, the bold aviatrix, movie stunt pilot, and owner of the Happy Bottom Riding Club, the R&R hangout of choice for the of the most daring pilots at the Muroc/Edwards high desert air base.

Along La Cienega near Inglewood. At Beverly Hills High School. In people’s backyards in Echo Park. Atop Signal Hill. Oil wells are everywhere in and around L.A. You sure don’t see that in Paris (France).

And now we come to oil — among Los Angeles’ gifts of agriculture, aviation, real estate and movies, this was the dirty one. The lads of the private, male Uplifters Club out in the Palisades sang lustily, “Yes it’s oil, oil, oil / That makes L.A. boil!”

Two oilmen would come to grief, more or less, in the 1920s.

Back in 1892, Edward L. Doheny had taken a sharpened eucalyptus log and gone chonking into the soil of Echo Park, and struck oil. He became rich and respected but was brought to court in the Teapot Dome scandal over allegedly bribing Albert Fall, the secretary of the Interior, with $100,000 for the inside track on oil leases on federal property. Puzzlingly, the secretary was convicted of taking the bribe, but Doheny was acquitted of bribery — maybe because it was his son and his son’s valet who delivered the black satchel of dough to Fall, and the son and his valet had died in a still-murky murder-suicide in 1929.

This oilman here was not a nabob like Doheny, but his L.A. oil scandal was going on at the same time. C.C. Julian — Courtney Chauncey Julian, a name fit for a stage villain with a big mustache to twirl — came to town with a scheme that would enrich himself and a few others and bankrupt hundreds of his fellow Angelenos.

A Canadian who had worked the oil fields in Texas, he borrowed money to buy four acres of land in Santa Fe Springs, struck oil, and decided to leverage his strike into a full-service oil producing and refining company, Julian Petroleum.

So well known was he that people around town called his company by a nickname, “Julian Pete.” Julian sold $11 million worth of stock to 40,000 Angelenos, some rich and famous, some living on hope and orange juice. Julian gave them headlines. He sprawled and brawled, left monster tips, flew in his own plane and abluted in a gilded bathtub.

One night in January 1924, he slugged one of the most famous men in the world, Charlie Chaplin, at Club Petroushka on Hollywood Boulevard. Chaplin was sharing a table with Russian aristocrats and violinist Jascha Heifetz and saw Julian and his buddies kick over a lamp and generally behave like ruffians.

Chaplin asked them to stop; there were ladies present. Julian “lurched toward me,” Chaplin stated, “striking at me while I was seated at the table.” Chaplin hit him back and Chaplin’s friends — including a Russian novelist who could bend a dime in half — made sure Julian stayed down. Julian swore he was in San Francisco at the time.

Pretty soon the squeeze was on. Julian looked to be selling more than his wells could satisfy, but still taking in money from new investors to pay others — a classic pyramid operation. The big oil boys like Standard Oil, the state authorities and the newspapers pretty much locked down his activities, and in 1925, he resigned and gave control to a couple of questionable operators who forged and sold more than three million shares of fake stock. The ritziest pool of investors, which included senator Frank Flint and his brother, Motley, still got paid.

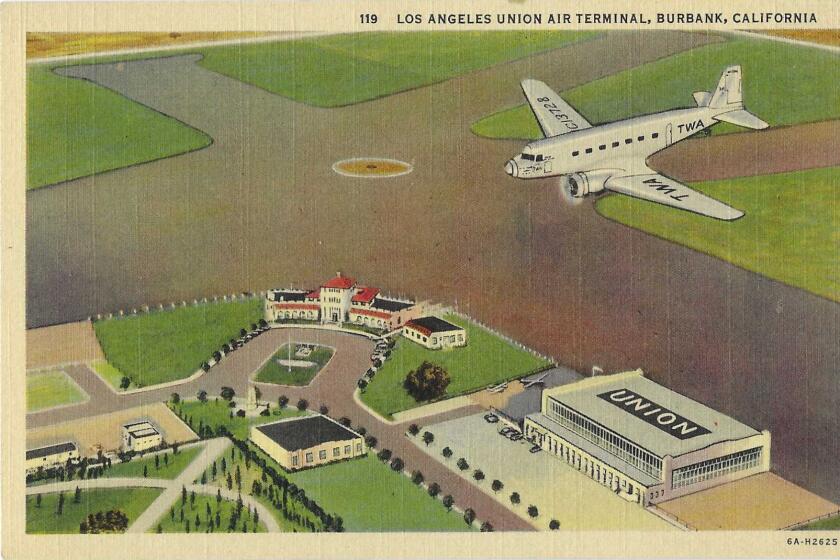

We still have lots of airfields, but gone from the landscape are the runways — near Griffith Park, near Wilshire and Western, in the Palisades — that could have challenged LAX for air superiority.

But Saturday, May 7, 1927, the roof caved in. Julian Petroleum stock was shut down. Thousands lost money and some lost everything. And so began, as historian and essayist Carey McWilliams wrote, “the long and sordid aftermath involving jury fixing, bribery, and murder.”

Julian, who flitted back into town to gin up public sentiment on his radio station, was not tried; the men who were, were acquitted. Motley Flint was shot to death in court in an unrelated case by an Inglewood real estate agent who fired three shots, threw the gun at Flint and yelled, “This fellow ruined me! He ruined me!”

It seems the only man who went to prison in the Julian Pete scandal was the Los Angeles district attorney, who’d been taking bribes from Julian and repaid him by refusing to prosecute.

But soon Julian was in hot water again, this time with the feds, for oil misdeeds in Oklahoma. He jumped bail and went on the lam to Shanghai under a fake name. Enough of the old Julian remained for him to brag that “some day, when China is peaceful, I will develop the oil fields of northwest China and then maybe I will have the last word with the Standard Oil Company.” But U.S. law was empowering fugitive citizens to be arrested abroad, and in 1930, Julian died by suicide at Shanghai’s Astor Hotel.

Writing in Sunset magazine in 1927, in an article sub-headlined “Why the Horses Laughed in Los Angeles,” Walter V. Woehlke described a master con man — not Julian — who, “whenever the authorities or his creditors go after him… made his followers believe the authorities were their enemies … got their sympathies …and made them put up the money for each new fight.” (It sounds like an early 20th century Trump playbook.)

Woehlke used that to explain why Angelenos were ripe for Julian Oil’s plucking, gullible with the “naïve credulity” that came from seeing a flourishing city rise up quickly from almost nothing. Why couldn’t the same happen to them? “That’s why Los Angeles still fervently believes in Santa Claus.”

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.