The ghosts of L.A.’s unbuilt freeways — a wide median here, a stubby endpoint there

Maybe you can hear them whispering, as your tires hiss along freeway concrete: the almost-weres, the might-have-beens, the freeway ghosts of Los Angeles, the thoroughfares dreamed up, planned for, but never built.

There are more — oh, so many more — than you might have wished or feared, even in the cloverleaf heart of Freeway L.A.

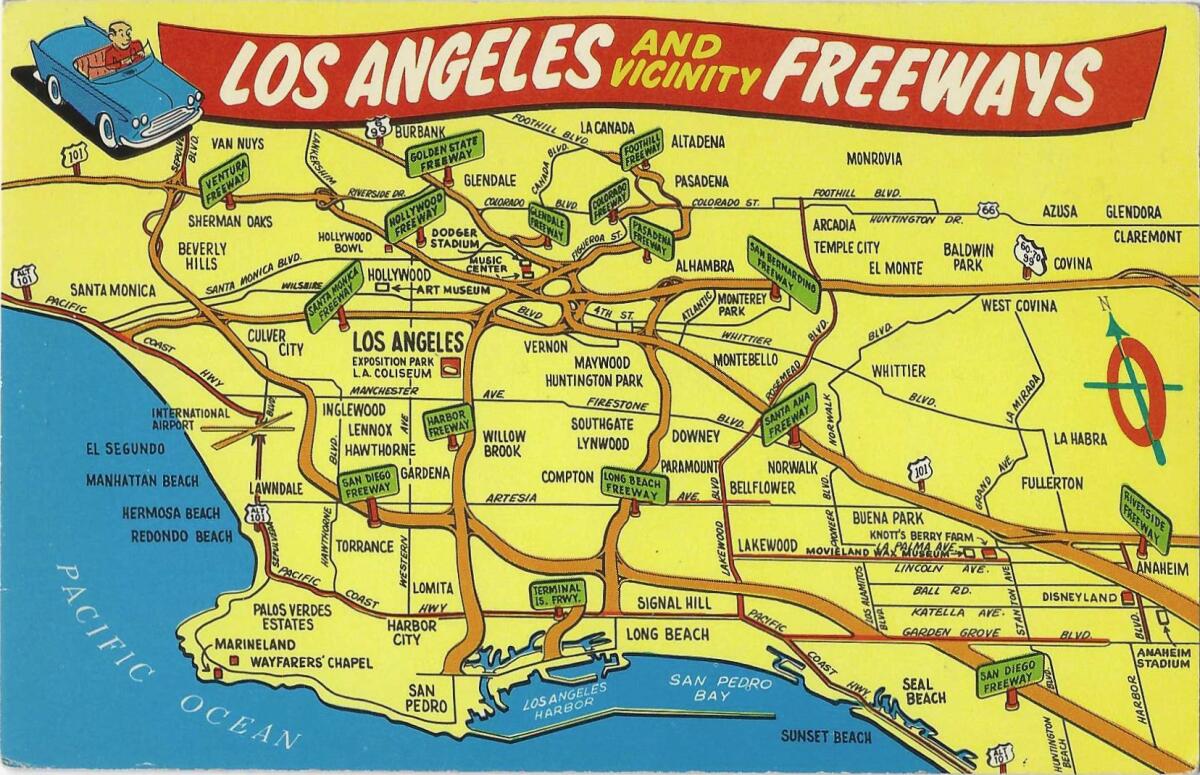

The Whitnall Freeway, the Industrial Freeway, the Temescal Freeway, the Laurel and Topanga and Malibu Canyon freeways, the Sierra Freeway, and the legendary Beverly Hills Freeway, discarded like an unproduced screenplay when such stars as Lucille Ball and Rosalind Russell gave it a big N-O.

Imagine all of them were there, with those wide, relentless rights of way that cleave cities and freeze the community blood.

To the roll-call of only partly built freeways — the Glendale Freeway, the Slauson/Nixon/Marina Freeway — you can add the Long Beach Freeway. Just last month, the county’s transportation authority threw in the trowel and gave up on widening about 20 miles of the 710 through southeast L.A. County. This happened more than two decades after a federal judge rendered the other end of the freeway DOA, sealing up the piggy bank on buying property to extend the 710 through El Sereno, South Pasadena and Pasadena to join up with the Foothill Freeway.

The great age of freeway building here lasted only a fraction of the time that the freeways themselves have: from the end of World War II to about 1970. At mid-century, the state was ready to build out an iron-waffle grid for Los Angeles that planned a freeway no more than four miles from the next one. Four miles!

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

The big “oomph” of federal dough for freeways began with President Eisenhower’s 1956 interstate highway program. It was an offer California could hardly turn down: freeways, 90% off! Buy now! The feds picked up 90% of the tab for building an interstate highway. As the years went by, the jingle from the federal piggy bank diminished, but the freeways stayed on the drawing boards and in the minds of highway project planners.

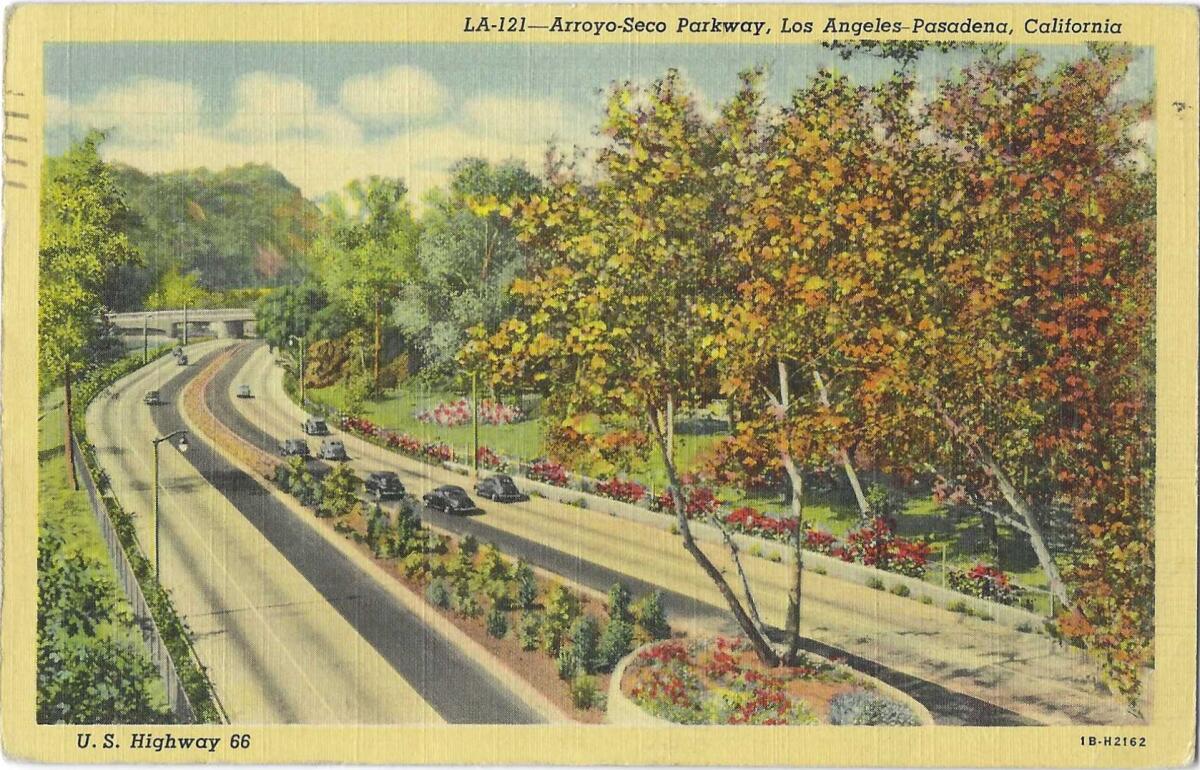

The audacious 1930 Olmsted-Bartholomew plan — commissioned and then ignored by the Chamber of Commerce, with its vision of a coherently green and pleasant L.A. — did accommodate cars into the designed civic fabric, with “parkways,” roads following natural terrain and fringed with trees and plants like a country lane. The only actual route that lived up to that was the Arroyo Seco Parkway — you know it as the Pasadena Freeway or the 110 north of downtown — which opened in segments beginning in 1940. In 1943, a city planning document showed the Ramona and Santa Monica, Harbor and Hollywood parkways still hopefully penciled in.

The language changed with the mission. “Parkway” and shared beauty surrendered to “motorway” and single-car speed. And then came “freeway,” unadorned, utilitarian, shorn of any charm but time-travel.

The California freeways’ greatest champion was Randolph Collier, a state senator from Siskiyou County, an ornery corner of the state about as far north as you can get without being Oregon. As a pro-gas-tax Republican who ran the state Senate’s transportation committee, he wielded his swift gavel like a magic wand to conjure freeways and make public transit projects disappear. He considered San Francisco’s fledgling BART system to be a “test tube,” and as for rapid transit, he called it “rabbit transit. … Whatever it is, it’s no damn good.”

Some freeways were never much more than lines on maps — sometimes just one map, before the line was redrawn or erased.

Some changed names once they were being built. The Glendale Freeway was originally the Alessandro Freeway, named for the Edendale street where L.A.’s first silent film studios, like Mack Sennett’s, were enthralling the world when Hollywood was still a prim town that barred demon rum and actors. The Glendale Freeway, so broad and steep where it joins the 210 Freeway around Descanso Gardens, dribbles into a little nub at its southern end, wide freeway lanes squeezed with black-hole-sucking intensity into little Glendale Boulevard, near where the eastern end of the Beverly Hills Freeway was to have joined the Glendale Freeway — but more about that below.

Freeway names and numbers

We mostly know them by their numbers, but Southern California freeways also have names, sometimes more than one. Here are a few.

The 2: Glendale Freeway

The 5: Golden State / Santa Ana / San Diego Freeway

The 10: Santa Monica / San Bernardino Freeway

The 90: Marina / Richard M. Nixon Freeway

The 91: Gardena / Artesia / Riverside Freeway

The 101: Hollywood / Santa Ana / Ventura Freeway

The 105: Glenn Anderson / Century Freeway

The 110: Arroyo Seco Parkway / Harbor / Pasadena Freeway

The 134: Ventura Freeway / President Barack H. Obama Highway

The 210: Foothill Freeway

The 405: San Diego Freeway

The 605: San Gabriel River Freeway

The 710: Long Beach Freeway

What is now the Santa Monica Freeway first went by the drafting-board name of Olympic Freeway, for the boulevard it would parallel. The Sepulveda Freeway, first suggested in the years before World War II as a path between Ventura and Pico Boulevards, became the San Diego Freeway. In the early 1970s, the U.S. Transportation secretary loved a plan for a freeway-paralleling “high-speed tracked air-cushioned vehicle system” to zip passengers 16.3 miles from the San Fernando Valley to the airport in 15 minutes. Well, who wouldn’t?

The Industrial Freeway concept replaced the earlier Terminal Island Freeway, also unbuilt, intended to be a zippy concrete path from the port to downtown L.A.

The Los Angeles River Freeway, from Long Beach to San Fernando, was also a line on a map in the months before the war ended, when future President Eisenhower was still Gen. Eisenhower, directing tanks and troops in Europe. With tweaks and trims, it became the 710, the Long Beach Freeway. Urban archeologists millennia hence may be puzzled by an orphan stub of it, relic of the abandoned Pasadena part of the 710, that takes a driver off the eastbound 134 Freeway a swift fraction of a mile to its end at California Boulevard.

Waiting till the last moment to merge — say, when two lanes become one in a road construction zone — actually makes traffic move faster.

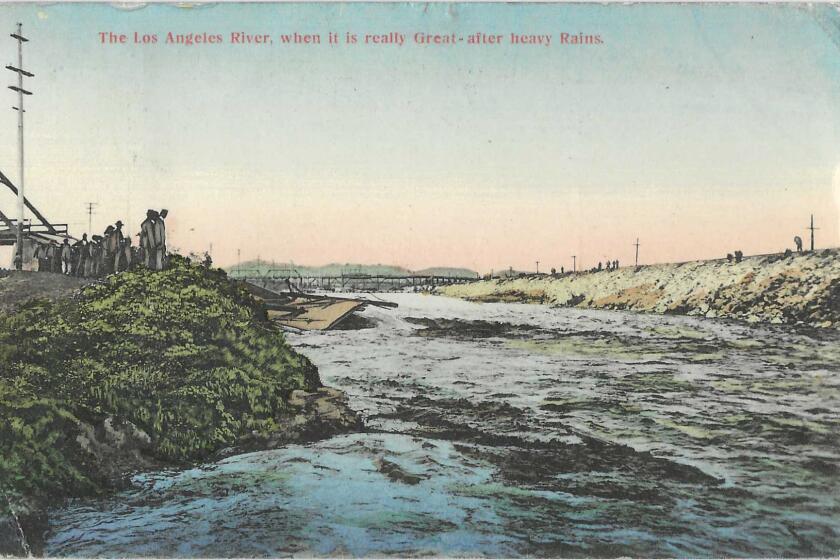

The intended Riverside Freeway had nothing at all to do with the Inland Empire city and everything to do with the fact that the freeway, like the so-named street, would run along the L.A. River, which may have more concrete in it than an equidistant piece of freeway.

In 1954, the state highway commission was still calling it the Riverside-Ventura Freeway, but even though Ventura was a distant destination, the river was so quickly effaced from memory that it soon disappeared from the double-barrelled freeway name too.

The Ramona Parkway (or freeway), planned in early 1940 from Vignes Street downtown east to the city limits, became the founding piece of the San Bernardino Freeway.

The Redondo Beach Freeway really is a freeway, except it’s called the Gardena Freeway by no one except perhaps Gardenans; everyone else calls it the 91, and, as it moves east, becomes the Artesia Freeway and then the Riverside Freeway, the one that’s not about the L.A. River.

The ones that didn’t happen, for which you may breathe a prayer of gratitude to the cosmos as you read:

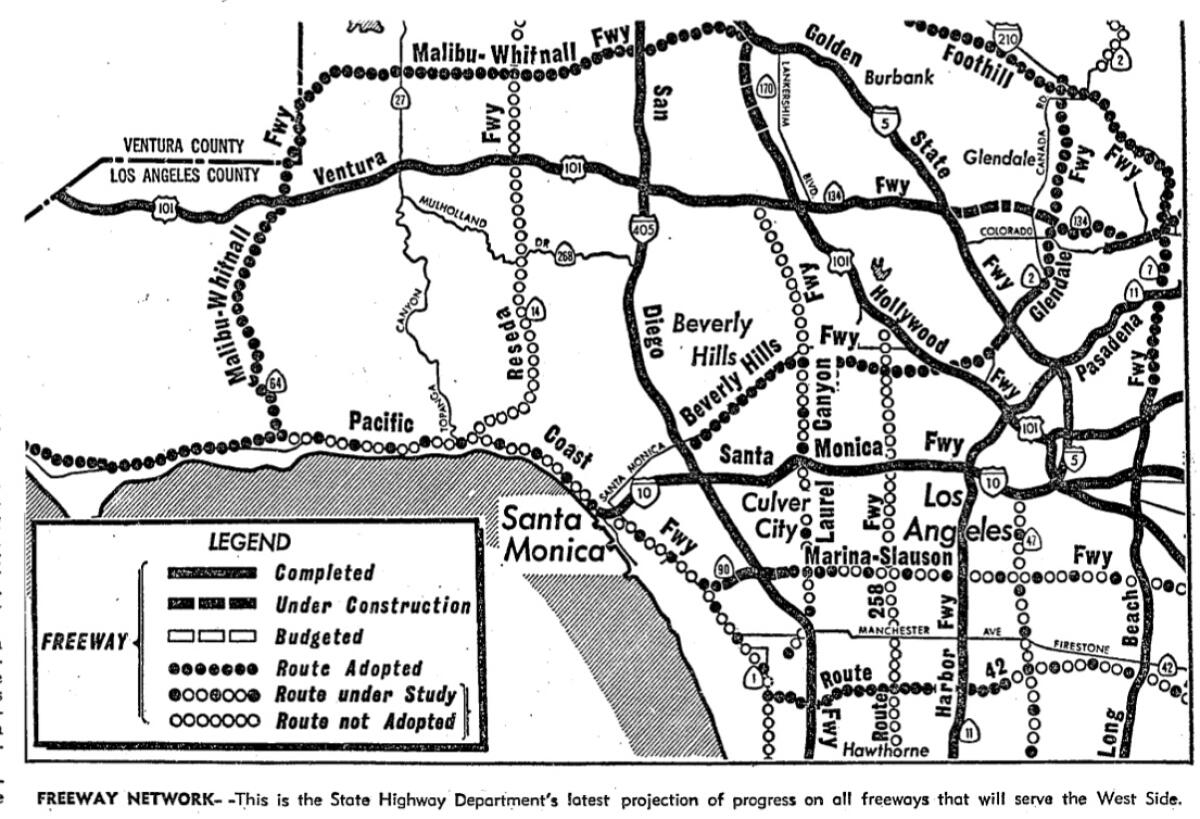

The Whitnall Freeway would have run for 27 miles, from the ocean through the Santa Monica Mountains via Malibu Canyon, up to the west end of the Valley, then turned east over the Valley floor to meet up with the Hollywood and Golden State freeways — possibly running parallel to and between the actual Ventura and 118 freeways, like the concrete in a concrete sandwich.

After one too many floods, L.A. turned its river into a concrete channel. Today and in the future, the river could be part of the answer to some of the city’s problems.

One of the several routes for the Whitnall Freeway planned for it to run underground below Mt. Lee, where the Hollywood sign now stands. Back in 1929, as the region was just getting its highway plans in order, and freeways were still some distance away, the Griffith Park Tunnel Assn. was champing at the bit to get “twin bore” drilling underway for parallel tunnels, 20 feet wide and 3,580 feet long, to connect Hollywood and the San Fernando Valley.

George Gordon Whitnall was Los Angeles’ first city planner, the son of the man who helped to create Milwaukee’s county parks. He was evidently named for the poet, George Gordon Byron, aka Lord Byron, and Whitnall’s vision for L.A. held the poetic — “Los Angeles is predestined to be the greatest city on the American continent” — coupled with the practical — “Thus far we have just ‘happened.’ We must now plan.”

The Reseda Freeway would have taken drivers from the ocean through Rustic Canyon in Pacific Palisades, over the Mulholland crest, and north paralleling Reseda Boulevard, through Porter Ranch and the Santa Susana Mountains to Newhall and beyond. The very magnitude of its ambition may have done it in.

You can see a smidge of what the Laurel Canyon Freeway was meant to be if you take the in-the-know back way to LAX, over La Cienega at Ladera Heights. There, at Slauson Avenue, a mile or two of wide, wide roadway shows where the Laurel Canyon Freeway would have been built — from LAX to a spot worryingly close to the Hollywood Bowl and over the Hollywood Hills through Laurel Canyon. Laurel Canyonians lobbied ardently to kill the plan, and by 1972, Gov. Ronald Reagan and the city of L.A. did as they asked.

The original Slauson Freeway — oh, there were big plans for this one: 40 miles, from PCH to the Riverside Freeway (the 91 one, not the L.A. River one) at Yorba Linda, birthplace of Richard Nixon. Instead, Route 90 shriveled into two rather pointless bits: about three miles of it from the San Diego Freeway to PCH at Marina del Rey, and, way, way inland, the don’t-blink-or-you’ll-miss-it Yorba Linda Freeway, now surviving just within the Yorba Linda city limits as the Richard M. Nixon Parkway.

Moviemakers, painters and authors have long opined on the quality of L.A.’s light. A Caltech scientist illuminates on why our light is so remarkable.

Paul Haddad, the author of “Freewaytopia: How Freeways Shaped Los Angeles,” figured out why so many of these sad stumps exist. Part of it had to do with “spend-it-or-lose-it” federal freeway budgets.

“You find a lot of these also-rans on freeways that were built in the 1950s or early ’60s, when they envisioned future freeways branching off of them. It was more financially expedient to simply ‘bake in’ future junctions while they were constructing, say, the Hollywood Freeway — thus, the widening of the median by Vermont [Avenue] to accommodate the future Beverly Hills Freeway. Imagine how much more costly it would be in the ’70s if they had to reconfigure the Hollywood Freeway after getting a greenlight to build the Beverly Hills Freeway.”

Haddad explained the same mystifyingly vast median space at Highland Avenue on the 101, the spectral leftovers of where the Whitnall Freeway was to have crossed the Hollywood.

In 1971, Republican state Assemblyman John Briggs finally got his wish: to name the entire planned Slauson Freeway for Nixon. He even offered to name one offramp for ex-president Lyndon Johnson, just to get the mighty Randolph Collier’s cooperation.

It was a Pyrrhic triumph. Come 1974, Watergate would obliterate that name, and the three-mile stub became the Marina Freeway. I believe ardently that the Marina Freeway is way overdue for a more fitting name. Call it the Ballona Freeway, for a living, natural feature, the Ballona Creek, where L.A. River water once flowed copiously to the sea — not for a manmade place like Marina del Rey.

The proposed Pacific Coast Freeway would have been PCH on steroids. It would have run from Newport Beach to above Malibu, and — if some bold-minded planners had had their way — it might have run entirely offshore, above the water, on a stilt highway. This plan was killed off piecemeal in the early 1970s.

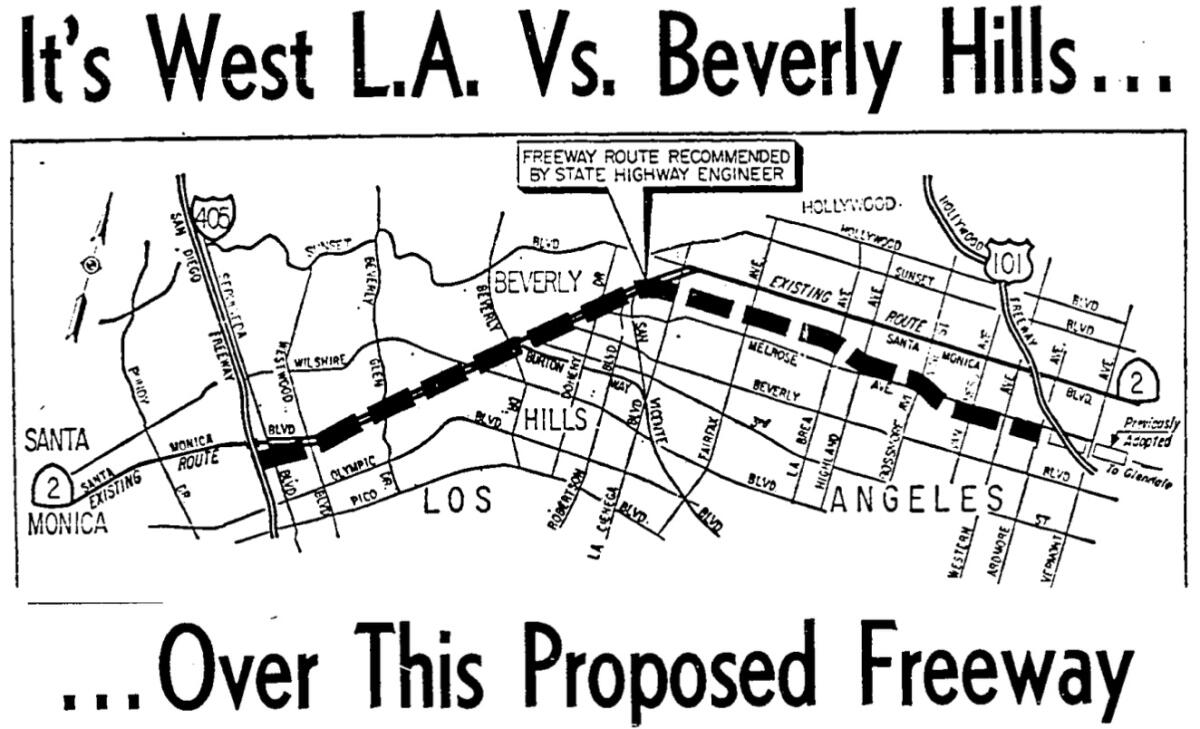

You may have noticed — and if you haven’t, you will now — that there’s an uncommonly wide bit of median land where the Hollywood Freeway crosses Vermont Avenue. That’s where the Beverly Hills Freeway was meant to intersect with the Hollywood Freeway. But it was not to be, because …

Beverly Hills.

It looked for one hot minute like there really would be a Beverly Hills Freeway, crossing town from Echo Park to the 405. Beverly Hills had agreed grudgingly and in principle to let a 10-mile, maximum 10-lane freeway run through town, so long as it was dug down at least 20 feet below ground level, its hideousness concealed from residents and real estate appraisers under a camouflaged “cut-and-cover,” and also that there would be no on- or off-ramps in BH itself. Last year, with the prospect of the Purple Line coming through — and even, oh mercy, stopping in — Beverly Hills, a Times reporter talked to Sarah, just Sarah, thank you, a Beverly Hills woman eating at Pinches Tacos in Westwood. What she said about the Purple Line sounded very much like the mutterings about the BH freeway decades before: “Crime is already on the rise, and we don’t need more access to these neighborhoods that are relatively safer. It will bring quite a lot of riff-raff.”

Gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, whose real estate stake in Beverly Hills was the home she called “The House That Fear Built,” wrote in 1963 of her fellow locals that you could “steal their girls, beat them at poker, take away their star billing, but invade their homes, and you’ve got a fight.”

The path of this freeway was a rich-versus-richer fight card. One route would have barreled through the fabled estates of Beverly Hills roughly across Sunset Boulevard, and the other would have tracked along Santa Monica Boulevard to the south. The two sides kept pushing the route line back and forth between them like a limp noodle.

As everyone knows, there is no Beverly Hills Freeway. The lobbying and lawyering and movie-starring, along with the prices for the rights-of-way, got it erased from the freeway map.

Generals and outlaws, heroes and villains: L.A.’s parks are named for a colorful cast of characters.

It was the ’60s, and then the ’70s, and by then the antiwar movement had shown people the power of protest, and they used it against freeways. Bay Area voters began a “freeway rebellion” against two freeways, and won. Under Gov. Jerry Brown, transportation money began to be doled out to “rabbit” transit projects too. The price of land rights-of-way was getting ridiculous. Angelenos had had enough with smog chuffed out from car exhausts, and from behind their own steering wheels, they weren’t seeing that more freeways made traffic better. The fact that master-planned regional freeways had to pass through cities that had to approve the routes made them vulnerable to being taken down, segment by segment. One state highway engineer mourned the public’s apparent belief that “if you get rid of freeways, you won’t have any problems.”

All of this broke like a perfect storm over what turned out to be the last real freeway to be built in L.A. County, the I-105, officially the Glenn Anderson Freeway, originally the El Segundo-Norwalk Freeway, known ever after as the Century Freeway. And yes, the joke was that it took that long to build.

In fact it was closer to a third of a century, three times longer than most other freeways. It was a gleam in planners’ eyes in the late 1950s, and it didn’t open to traffic until 1993, and only then after a stupendous battle that mustered every one of the objections above, as well as the fact that it plowed through neighborhoods and sundered cities. One class action lawsuit united the Sierra Club, the NAACP, and a South Bay town on the same no-freeway team.

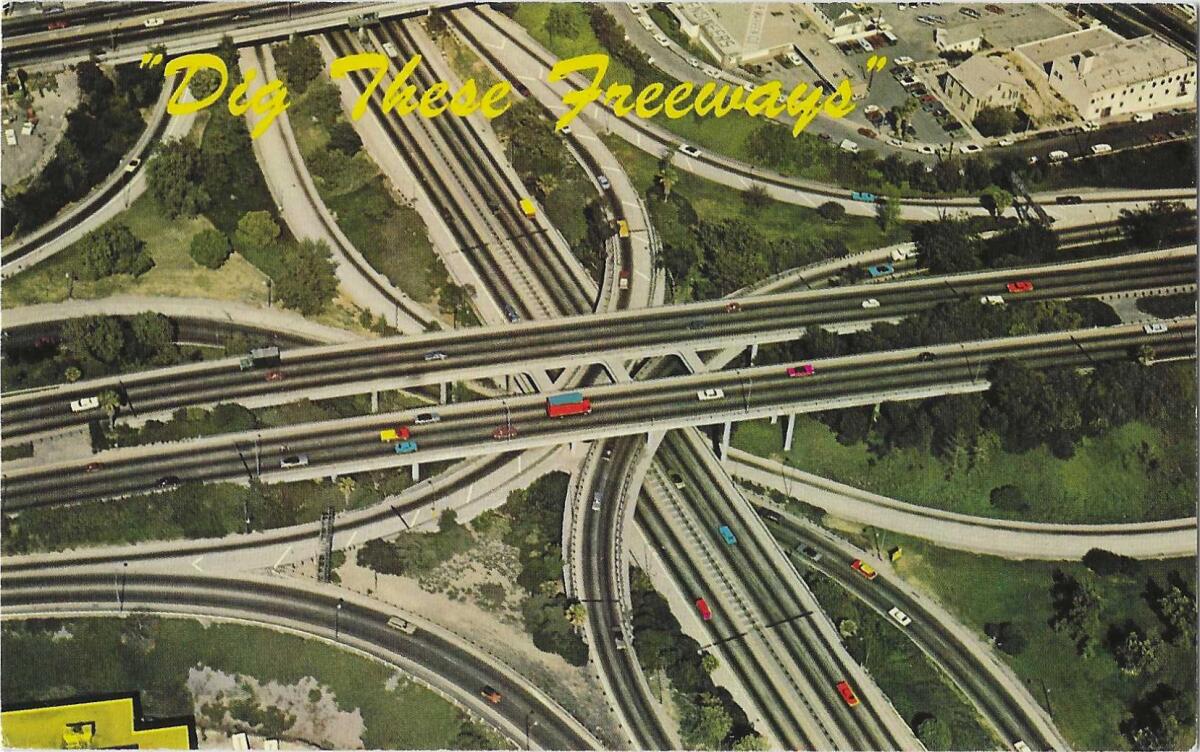

Now, you’ve probably driven it, and certainly seen it in movies like “Speed” and “La La Land”: that stupendous, almost-like-flying interchange of the 105 and the 110. It’s named for the late federal judge Harry Pregerson. In 1972, one month before what was supposed to be the freeway groundbreaking, Pregerson ordered the freeway stopped until matters that we would call social justice — pollution, housing disruption, civil rights — were resolved. Well, that changed the game for any freeway ever after. With soothsayer insight, an attorney for the class action plaintiffs decreed, “this may mark the end of the freeway era in the Los Angeles metropolitan regions.”

For the 105’s overtime grand opening, Gov. Pete Wilson cut a strand of silk poppies to open the freeway and rode down the lanes in a 1936 Auburn Boattail Speedster. He knew not how prophetically he spoke when he said, “You’re not going to see one like this again soon.”

Construction of the U.S. Interstate Highway System tore through the nation’s urban areas with freeways that, through intention and indifference, carved up Black communities

The Foothill Freeway, which flirts along the hem of the San Gabriels, took even longer than the 105, but it’s not considered the last L.A. freeway because its L.A.-area miles were completed in 1981. But its final 40 miles connecting to the 10 in Redlands weren’t road-ready until 2007. “From start to finish, it took fifty-two years to complete the Foothill Freeway — the longest timeframe in the Southland’s freeway system,” Haddad wrote.

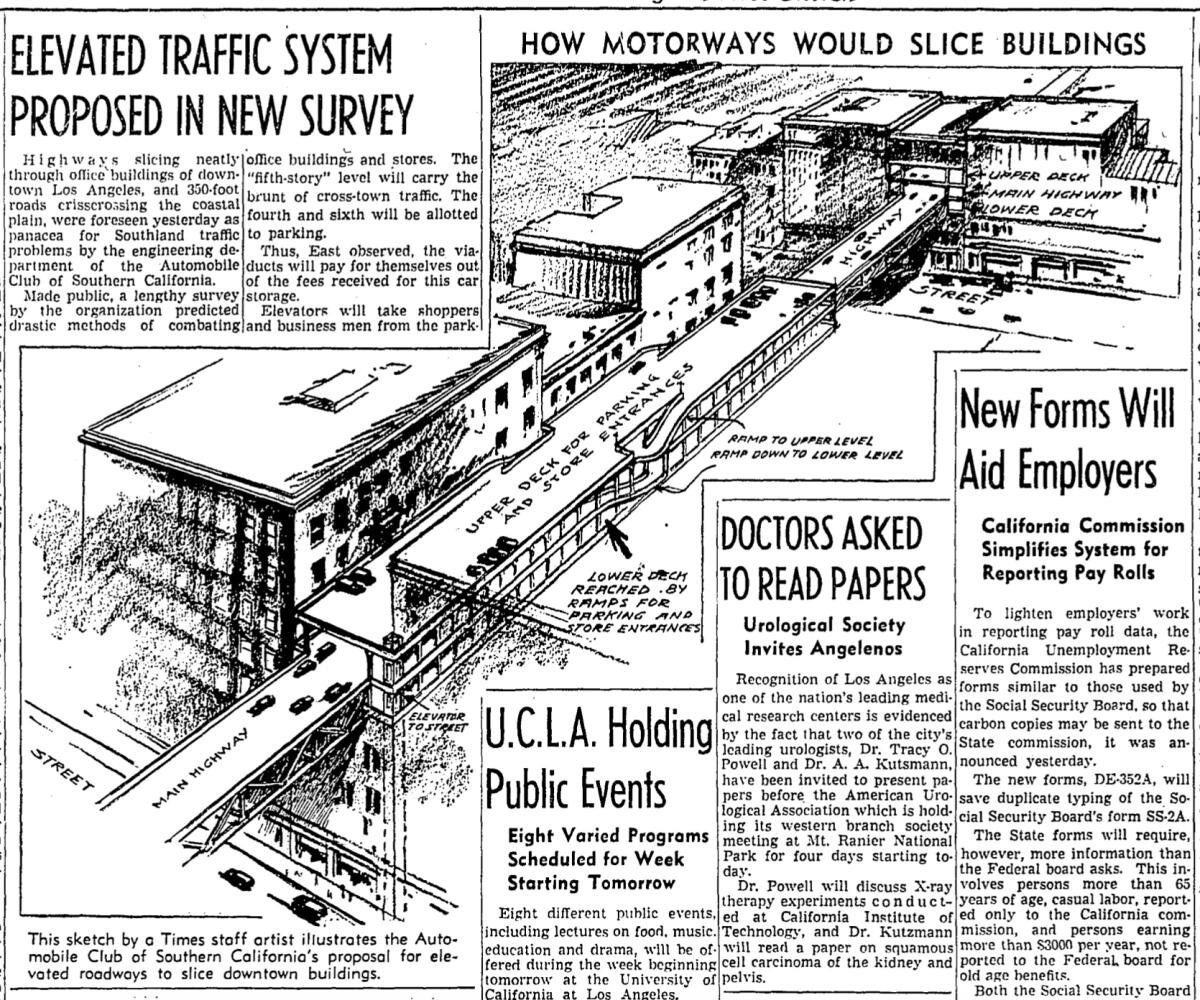

The hands-down best never-built freeway was a fantastically optimistic plan laid before Angelenos in 1938: 400 miles of elevated roadways “linking all parts of Los Angeles County with high-speed, intersection-free thoroughfares.” But the finest, most impossibly futuristic aspect of it was that, in crowded downtowns, these elevated motorways would be cut right on through buildings, at the third or fourth floor, putting freeway traffic 30 or 40 feet above the bustling sidewalks below.

It’s an ideal fit for the city of cars, the city of the future. And if they had indeed started it in 1938, it might almost be finished by now.

Who is Griffith Park named for? What about Vasquez Rocks? The Broad? Mt. Baldy? Here are the namesakes of L.A.’s best-known landmarks.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.