A half-century after being uprooted for a remote U.S. naval base, these islanders are still fighting to return

Reporting from Pointe aux Sables, Mauritius — The memories remain fresh in her mind: the fishermen tramping in from the surf with armfuls of fresh catches, the Saturday night dance parties under swaying palms, the long Sundays swimming in crystalline waters until her parents called her in for dinner.

“I will never forget those days,” said Noella Gaspard, 55, describing her childhood on the island of Diego Garcia.

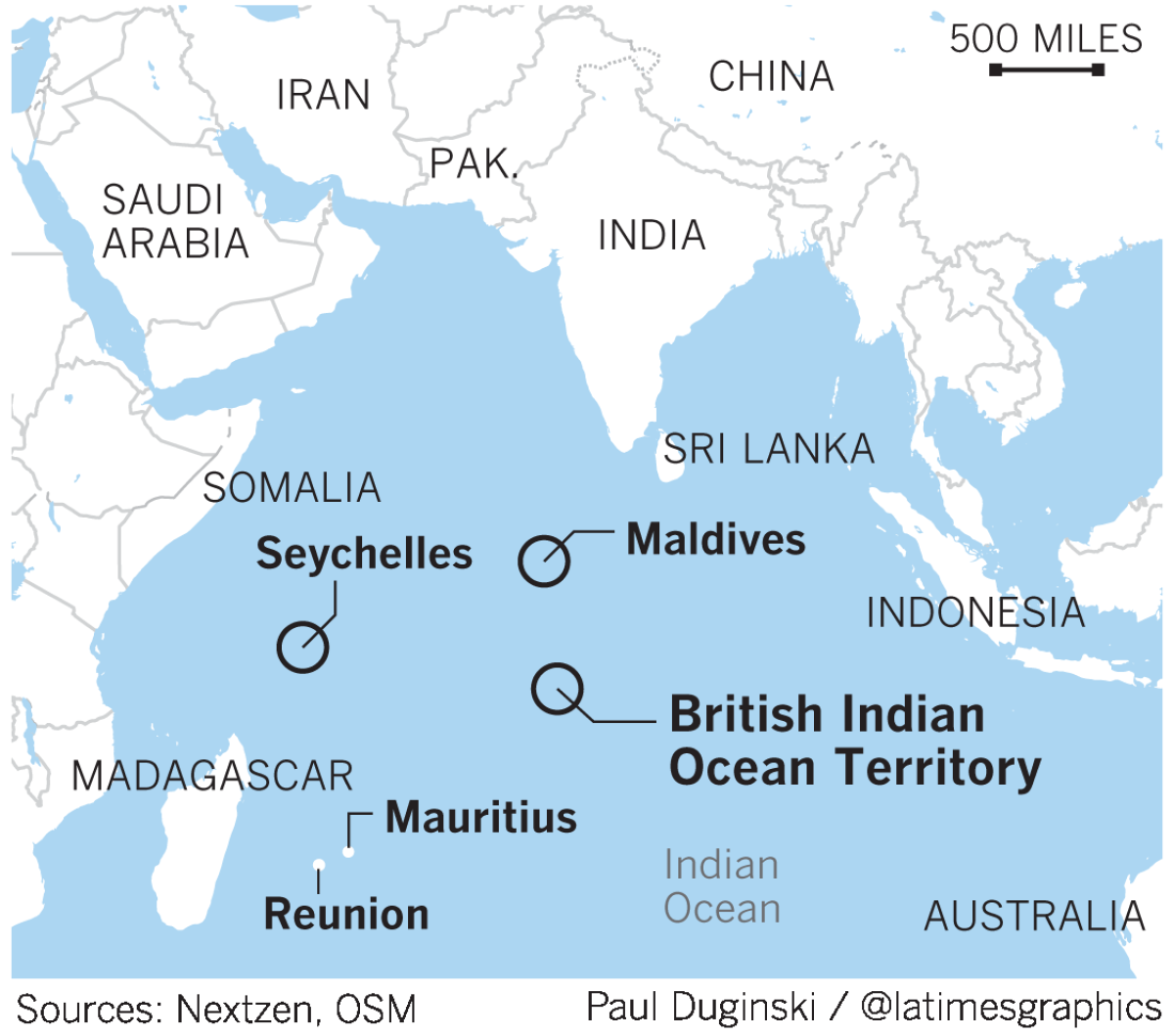

The footprint-shaped atoll lies in the middle of the Indian Ocean, at the tip of a chain of coral islands whose tropical beauty belies a difficult history.

When Gaspard was a girl, the archipelago was named Chagos. It was part of the British colony of Mauritius and home to 2,000 people who made their living on coconut plantations.

But in a 1965 military deal with the United States, Britain detached Chagos before granting independence to Mauritius three years later. Renaming the islands the British Indian Ocean Territory, Britain forcibly expelled all the inhabitants from 1968 to 1973 and leased Diego Garcia to the U.S.

There, the Pentagon went on to build one of its most important overseas bases, a launchpad for B-52s and stealth bombers into Iraq and Afghanistan — and an alleged “black site” where the CIA covertly detained terrorism suspects.

The deportees, who were dumped into poverty 1,200 miles away in Mauritius or in the equally distant Seychelles, have spent the last five decades battling the British and U.S. governments for the right to return.

Next month their struggle will land in the International Court of Justice in The Hague, which is scheduled to hear arguments in a case over whether Britain violated Mauritian sovereignty when it grabbed the islands for itself.

The court’s opinion is nonbinding. But if the 15-judge panel endorses Mauritius’ claim over the islands, it would lend support to the campaign to resettle the archipelago — which the deportees still call Chagos — and address what critics describe as one of the most shameful episodes of the end of the colonial era.

“There was a population living in peace and harmony for generations, and they just tried to discard us,” said 54-year-old Olivier Bancoult, leader of the Chagos Refugees Group, a community of exiles in Mauritius.

Only about 460 of the original exiles are still alive, he said. He was a boy in 1968, when he and his family traveled from Chagos to the main island of Mauritius to seek medical treatment for his baby sister after a cart ran over her foot. After she died, their mother went to book passage on a ship back home. But she was told: “The islands are closed.”

“My great-grandfather was born there,” he said. “Our culture and traditions are based there. All we want is the right to go home.”

The U.S. firmly opposes resettlement of any of the 60 islands in the chain — Diego Garcia being the biggest — for reasons expressed most clearly by a former American ambassador to London, Robert H. Tuttle.

In a 2006 diplomatic cable published by WikiLeaks, Tuttle wrote that U.S. officials had made it clear to Britain that “security around Diego Garcia would be difficult to ensure if resident populations were nearby.”

British authorities have complied. In 2016, following what it described as a comprehensive review of the issue, the government said it had decided against repopulating the islands. Among the reasons it cited was the presence of the base, which it called “a vital part of our defense relationship … used by us and our allies to combat some of the most difficult problems of the 21st century.”

The U.S. Naval Support Facility on Diego Garcia, which the Navy dubs the “footprint of freedom,” lies halfway between East Africa and Southeast Asia, with a 2-mile-long runway and an 80-square-mile lagoon deep enough to berth more than two dozen large ships. Its strategic value is matched only by its inaccessibility: Visitors are only allowed with permission from the military.

In the 1950s, Pentagon officials identified Diego Garcia as part of a plan to build military facilities around the world to counter the Soviet threat. The idea to dislodge the islanders came from the Navy, which pressed Britain to separate Chagos from Mauritius and demanded it be “without local inhabitants,” according to declassified documents detailed in “Island of Shame,” a 2009 book by David Vine, an anthropologist.

In exchange, Britain received a discount of $14 million on the Polaris, a U.S.-made nuclear missile, Vine wrote.

Aware of possible backlash, the allies agreed to portray the islanders as temporary workers. After the last residents had been banished, the State Department instructed officials to tell journalists that Diego Garcia “had no permanent native population.”

The base has since grown to house an estimated 1,700 military personnel and a roughly equal number of contractors. It includes all the comforts expected by today’s U.S. service member and more: a swimming pool, nine-hole golf course, spin classes, massage services, an outdoor movie theater, even windsurfing lessons.

The Navy’s website touts “unbelievable recreational facilities and exquisite natural beauty.”

::

Chagos had been continuously inhabited since the 1780s, when enslaved Africans were brought there to work on colonial coconut plantations. The French were the first to claim the islands, in the early part of that century, before losing them to Britain after the Napoleonic Wars in 1814.

After slavery was abolished, indentured laborers from India followed. By the middle of the 20th century, the islanders had grown into a small but distinct community with their own language, a French-based creole.

The plantations provided housing and weekly supplies of rice, flour and cooking oil. The islanders attended schools and churches in low, whitewashed villages that one colonial governor said were reminiscent of coastal France.

“We didn’t need refrigerators because we could go into the sea and catch fresh fish every day,” said Louis Rosemond Saminaden, an 82-year-old exile from Peros Banhos, one of several inhabited islands in the chain.

After its deal with the U.S., Britain began to restrict supplies to the islands. As deportation ships departed, some residents held out even as the plantations were dismantled and food ran low.

But in 1971, when the Navy arrived to begin clearing the beaches for construction, the evictions grew more urgent. In an apparent scare tactic, British and U.S. authorities executed the islanders’ dogs by corralling them into sheds and pumping in poisonous gas.

Two years later, a crowded cargo ship, its decks slippery with vomit, carried the last 125 deportees into port in Mauritius. The passengers refused to disembark for days until the Mauritian government agreed to provide them with housing — which turned out to be in shanties of the capital, Port Louis.

“There was no water, no toilets,” recalled Eliane Moutien, who was then a teenager. “We used gunny sacks to cover the windows because there was no glass.”

They were granted Mauritian citizenship, but the sad conditions, lack of jobs and discrimination they faced from locals — who taunted them as savages and mocked their accents — contributed to a profound longing for their homeland. The deportees call it sagren, and Bancoult believes it contributed to the deaths of his father and three of his siblings.

Some exiles fell into poverty, alcoholism, gambling and prostitution.

“To this day I don’t know how the British could behave like this — and with the complicity of the U.S.,” Bancoult said.

::

Efforts to hold American officials accountable have failed. In 2006, a federal appeals court dismissed a lawsuit Bancoult filed against former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, ruling that the U.S. government couldn’t be prosecuted for harm done to foreign nationals in another country.

That’s precisely the way the agreement with Britain was designed, according to Vine.

“The U.S. government has been very strategic in keeping their mouths shut and letting the British government take the heat,” he said in an interview. “That strategy goes back to the original idea of the base … and it has worked perfectly in the eyes of the U.S. military because they’ve had to face so little questioning.”

The exiles have had mixed success in British courts. In 2000, a British judge ruled that the expulsions were illegal and the islanders had the right to return.

Ten months later, however, came the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Robin Mardemootoo, a Mauritian lawyer who has represented the deportees, recalled the dueling emotions he felt watching the towers fall.

“I knew 9/11 was a tragedy, but I couldn’t help but telling myself that this is also the end of the Chagos litigation,” he said. “Given the importance of Diego Garcia for the U.S. military, I could not see any relaxation in the rules for resettlement now.”

In 2004, the British government passed an executive order that effectively blocked the judge’s ruling. The country’s highest court later upheld the order on national security grounds.

In recent years, voicing regret over the expulsions, Britain has offered the exiles modest cash payments, the right to claim British citizenship and occasional brief, supervised visits to the atolls. Bancoult and his mother, Rita, joined the first return visit in 2006. Landing on Diego Garcia, the mostly elderly exiles, escorted by military personnel, knelt before the gravestones of their ancestors, overgrown with moss and vegetation, and cried.

The exiles insist they have no problem with the base — they just want the opportunity to take some of the low-level contract jobs the U.S. military gives to Mauritians and Filipinos, or return to outlying islands more than 100 miles from Diego Garcia.

They believe the smaller islands have potential in tourism and fisheries, and they are due back in British court later this year to challenge the government’s contention that resettlement is economically unfeasible.

“We can’t accept that there are so many foreigners living and working in our birthplace,” Bancoult said, “and yet we have no right to go there.”

::

For now, the only path back to Chagos seems to depend on Mauritius regaining control of the islands.

After long ignoring the plight of the refugees on its soil, the Mauritian government — perhaps envisioning the islands’ economic potential — now says it views their resettlement and development as “matters of high priority.”

Last year, Britain fought in the United Nations General Assembly to keep the issue out of the international court — established to decide disputes between nations — but lost in a vote of 94 to 15. Britain’s main European allies abstained, a sign of how the Chagos episode has come to be seen, in the words of a former British diplomat, as “one of the worst violations of human rights perpetrated by the U.K. in the 20th century.”

But there is little indication that Britain would be swayed by the court, whose advisory opinions have been ignored before. In 2004, it ruled that Israel’s construction of a wall through the Palestinian territory of the West Bank was illegal — but Israel simply rejected the ruling and the wall remains.

“At best, it’s a condemnation,” Mardemootoo said. “But that is what we are hoping to achieve — that with international pressure, the U.S. and U.K. will back down.”

Britain has said it would hand the islands back to Mauritius when they were “no longer needed for defense purposes,” without suggesting a date.

The U.S. lease on Diego Garcia runs through 2036.

For many of the exiles, time is running out. Rita, Bancoult’s mother, died in 2016 at age 91. Saminaden, who said he wants to take his “last breath” in Chagos, is frail. The community now numbers nearly 10,000, with second and third generations that have never glimpsed the islands.

Gaspard, whose adult children are scattered between Mauritius and France, said Chagossians of all ages are bound by a desire to live again in their homeland.

“I hope I’ll be able to return before I close my eyes for the last time,” she said. “Even if I have to build a house of straw, I’ll go back.”

Shashank Bengali is South Asia correspondent for The Times. Follow him on Twitter at @SBengali

ALSO

The CIA closed its original ‘black site’ years ago. But its legacy of torture lives on in Thailand

The legend of the blond, blue-eyed slave: Retracing a crashed WWII pilot’s journey through China

For displaced Syrians, an offer to return home presents agonizing choices

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.