The legend of the blond, blue-eyed slave: Retracing a crashed WWII pilot’s journey through China

Almost everybody in Liangshan knows the story of the American slave.

During World War II, it went, an American aviator crash-landed near a village. The villagers had never seen a plane before, and they’d never seen a foreigner. Some believed he was an animal. But as they surrounded him and pulled his hair, rubbed his skin and heard him speak, they decided that he was, in fact, a human being.

The village elders said he was a gift, sent by the gods to become their slave. They shackled his feet and forced him to grind corn and tend livestock. He lived in the village for 10 years, until Mao Tse-tung’s Communist forces stormed the area in the mid-1950s.

For centuries, this had been one of China’s most forbidding places — an independent fiefdom the size of Maryland, so shrouded in mystery that it was marked “unexplored” on maps. The Chinese called the area Lololand, and the people Lolos, a derogatory term meaning “barbarians.” The Lolos — dark-skinned, tall and angular — maintained a caste-based, slave-owning society.

The Communists renamed Lololand the Da Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture — or Liangshan, for short. They abolished the slave system. They renamed the Lolo, calling them Yi.

And they found the American, or so the story goes, and sent him home.

I first learned of the tale of the American aviator in 2009, while traveling through southwest China on a Fulbright research grant. I was recording the folk songs of the indigenous people: sad, delicate refrains that strain upward like the area’s mountains. I followed winding roads to small villages, where I found the last remaining members of ancient family lines. I would ready my voice recorder, and they would sing.

During my stay in Liangshan, I heard the story of the pale stranger over and over, from dozens of people in dozens of villages. In Xichang, the prefecture capital, I heard it from Yi university students, government officials, accountants, waitresses and police officers. But back in Beijing, I could find nothing about the story online, nothing in Beijing’s National Library.

What began as an itch ultimately became an obsession. Over three years, I reviewed hundreds of pages of historical documents and interviewed dozens of historians, Chinese officials and former Yi clan leaders.

In spring 2014, I flew back to Xichang, now a city of 300,000 with a Pizza Hut, a KFC and several air-conditioned malls. A Yi historian had connected me with Shama Gupei, 77, a retired Yi police officer, and he agreed to meet me at a spartan government office in the city center. He had close-cropped silver hair and an air of folk wisdom.

In the 1950s, Shama told me, his superiors asked him to follow up on reports about an “American slave” in Liangshan. They were concerned the American was a spy. Shama interviewed villagers and filed a report. He found no evidence of espionage, but concluded that a tall Caucasian man, with blonde hair and blue eyes, had been kidnapped in Zhaotong — a small city in neighboring Yunnan province — then sold to one family, then another, then a third. That family lived in a village called Mayizu, deep in the mountains, near Liangshan’s far-off Jinyang County seat. He lived there for seven years.

I left for Jinyang the following day.

The city was small and congested, with muddy roads and dark, mildewed apartment blocks. Rain dripped off everything: the security cameras strung across power lines, the blackened woks of street-side food vendors, the canvas backs of motor rickshaws.

A Yi friend in Beijing had given me a number to call when I arrived, and I dialed it. Ten minutes later, an elderly man arrived. He was staggering drunk. He introduced himself as Old Bai.

“Follow me,” he said, pulling a flask from his jacket pocket. He led me to his first-floor apartment, a short walk away, then called the police.

Moments later, about 10 men arrived, all local government officials. They had crew cuts, and wore ill-fitting suits. I told them Shama Gupei’s story, and for about 10 minutes, they conferred in Yi. Then one turned to me. The slave’s name was Latie, he said in Mandarin. His master, Shama Qubi, lived in a village across the valley, about 15 miles away.

“Qubi’s wife is still alive,” he said. “She is over 80 years old. We can ask her. She should know.”

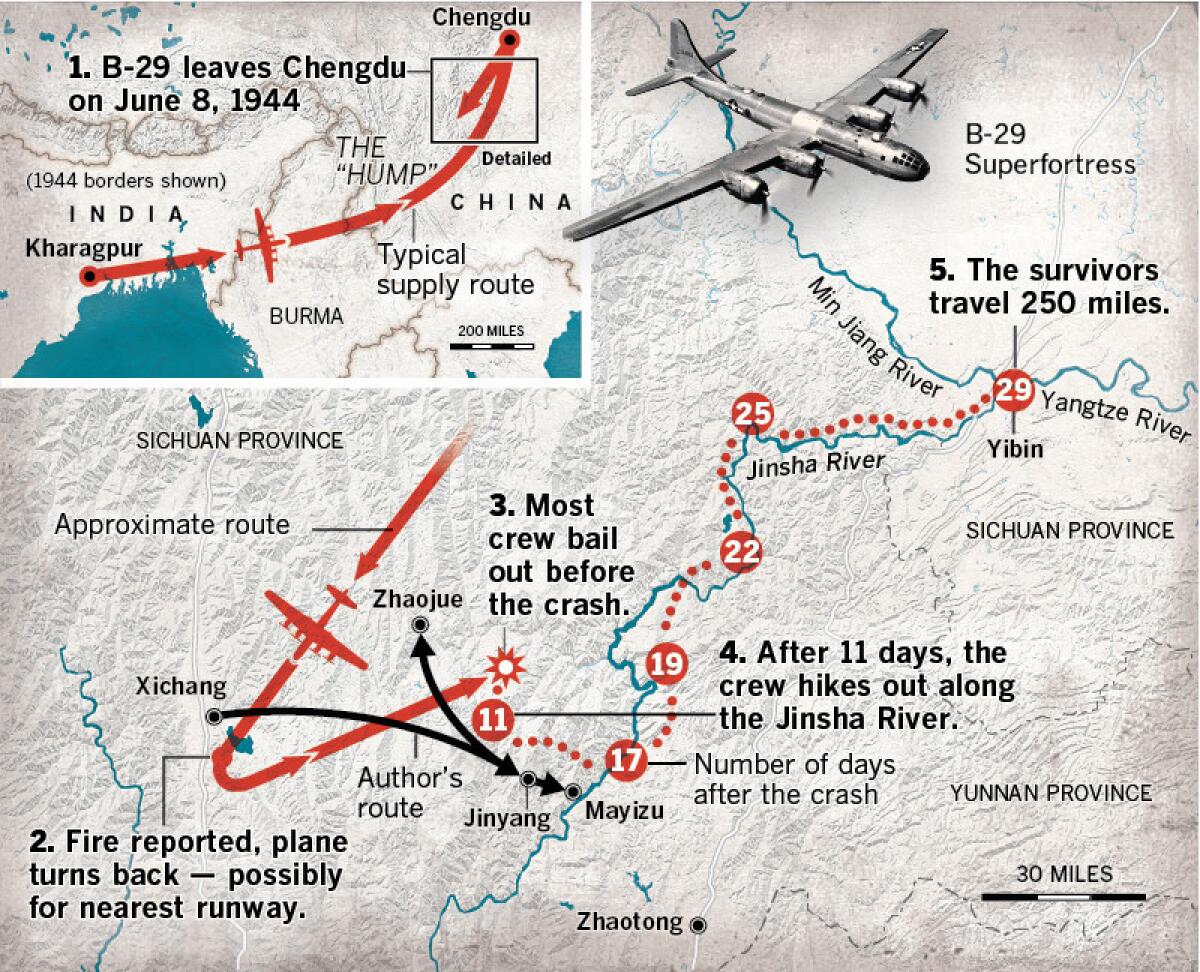

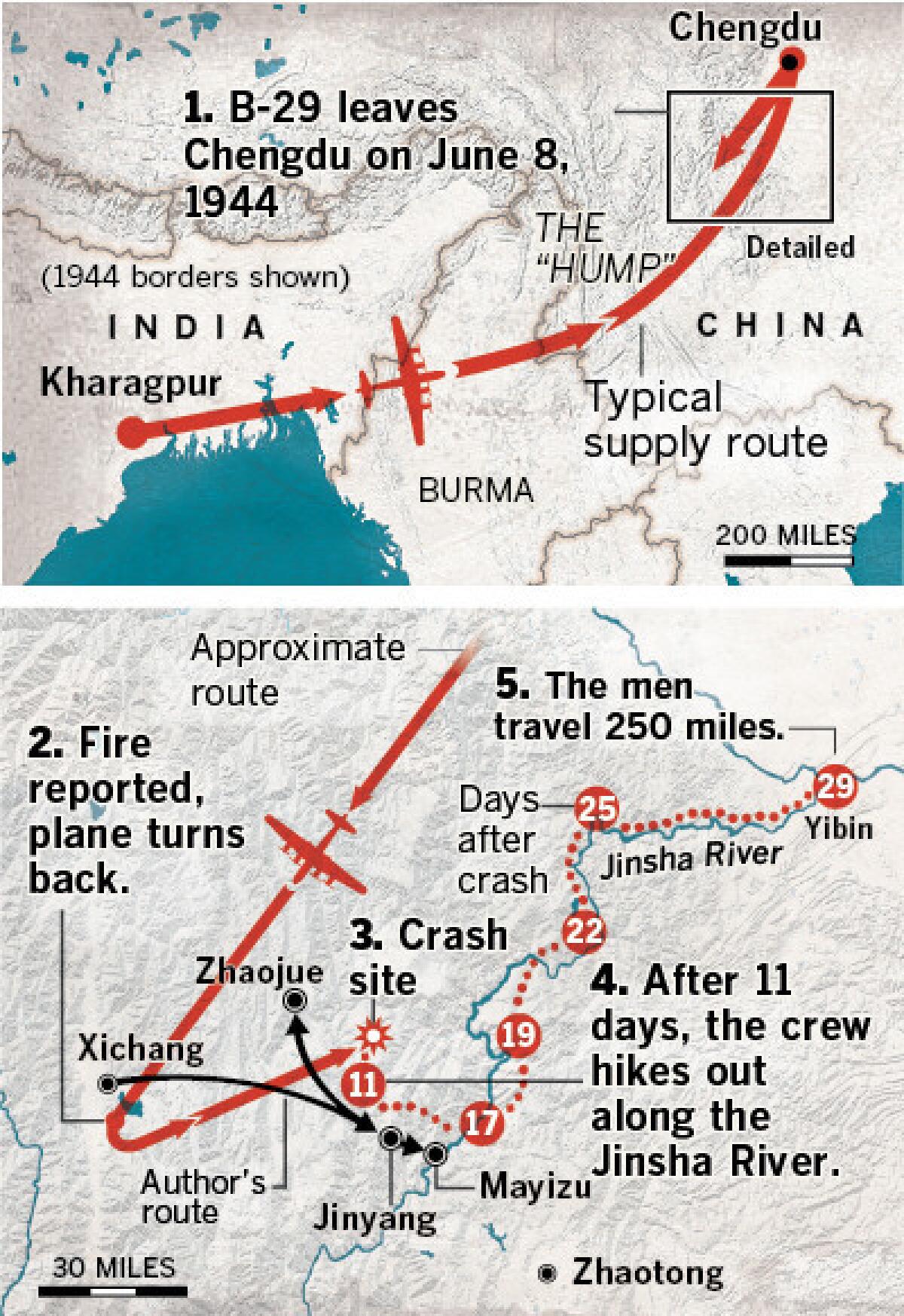

Two journeys through Lololand, 70 years apart

In 1944, Lt. Leslie Sloan and his crew bailed out over Lololand, a mysterious swath of mountains in southwest China, while flying the Hump, a World War II aviation route. In 2014, correspondent Jonathan Kaiman visited the same area, investigating rumors that a local tribe had held an American Hump pilot as a slave.

Sources: Mapzen, OpenStreetMap; Photo: US Archive. Lou Spirito / @latimesgraphics

In 1944, China teetered on the brink of failed statehood. The Japanese had occupied huge swaths of its east and northeast. China’s government — the Nationalists, led by Chiang Kai-shek — was struggling to defend major cities. The Japanese had recently occupied Burma, cutting off a key supply route, and the U.S., as a gesture of allied support, began flying cargo — food, weapons, fuel — from northern India to the southwestern Chinese cities of Chengdu and Kunming, to keep Chiang’s war effort afloat.

They called it the Hump, and it was perhaps the most treacherous aviation route in history.

During World War II, American planes were involved in 796 accidents in China, according to the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Agency, a Hawaii-based military task force that accounts for, and repatriates, Americans classified as killed or missing in foreign conflicts. Half of those accidents were catastrophic. Between 600 and 1,000 Americans went missing in the country — a full third of them in Yunnan province, which borders Liangshan.

World War II was a time of extreme upheaval, and the window for resolving its countless unsolved mysteries is closing fast. Last-remaining survivors are dying, documents fraying, plane and shipwrecks rusting away. Historians in China have it extra hard — the Communist Party, in power since 1949, is almost unparalleled in its will, and ability, to distort or suppress history that casts it in an unfavorable light. A story about a savage Chinese tribe enslaving an American pilot doesn’t fit the paradigm.

Yet a handful of Chinese academics and journalists, often living on the fringes of society, have structured their lives around cataloging such stories. Many told me that they were drawn to World War II’s ideological clarity; they considered it an escape from the banality and repression of modern Chinese life. Some had conducted research in Liangshan.

They gave me documents. And the documents traced the story’s genesis to June 8, 1944, when Garl Bud Ray’s plane fell from the sky.

On that day, Ray and the crew of his B-29 Superfortress — a silver, four-propeller plane with a wingspan nearly as wide as a football field — were soaring at 25,000 feet toward India after a successful supply run to Chengdu. Ray, the co-pilot, triggered the intercom, and in his Texas drawl, instructed the crew to check their parachutes and report back — just a precaution, he later recalled.

At 25, Ray was among the oldest of the 11 crew members. The others called him “Pappy.”

He was born in Fort Worth, in a small grocery owned by his parents. His father named him Garrell Bardin Ray, after a friend. When he was 9, he shortened it to Garl. He was affable and good-looking, with a narrow face and big, droopy eyes.

On the plane, Cpl. William Shufelt, a gunner, was shouting over the intercom.

“Lieutenant, we’ve got a fire,” he said.

Ray looked down at the instrument panel; as he did, an explosion rocked the plane. Soon, 1st Lt. Leslie Sloan, the plane’s captain, was losing control.

“What do you think?” Sloan shouted into the intercom. Ray had to think quickly. The mountains were 11,000 feet high, he estimated, and the plane was falling fast.

“We’d better get out of here while the gettin’s good,” Ray replied.

Again, he toggled the intercom: “You got your parachute on?” he asked the crew. One by one, they said they did. Sloan gave the order to bail, and they jumped.

Ray fell upside down, the wind whipping around him at 250 mph. He pulled his rip cord, but his parachute failed to open. He pulled it again. This time, the chute did open, but in doing so, it displaced his shoulder-holstered pistol, which cracked against his face, just above his left eye, knocking him unconscious.

When he came to, he could hear only the rippling of his silk chute. He felt something sandy in his mouth and realized that it was shattered teeth. Suddenly, the ground appeared. He saw cliffs and crags, peppered with scraggly trees, and he guided himself toward a level landing area. He dropped into a poppy field, surrounded by his parachute, and in a moment of quiet, he prayed.

The field was surrounded by boulders, and peeking out from above them, Ray saw faces. They were men. They were yelling. And they carried rifles.

“They were high-cheekboned, dark people,” Ray recalled. “And mostly, they wore goatskins or black silk-like stuff, and they had a topknot.” They were Lolos, and Ray would get to know them well.

The men closed in, and Ray — nose bloodied, teeth shattered — tried to fight them off but soon realized it was futile. The Lolos took the American’s weapons and vanished.

By 3 p.m. that day, nine of the plane’s crew had found each other. Ray and three others went to a nearby village, where they rested briefly. Then villagers led all of them into the mountains.

“We had to speak with sign language,” Ray recalled. “When you can’t talk somebody’s language, you don’t know what’s going on. You had to try to guess.”

They walked through the night and stopped at a mud-brick house. The owner gave them some ground wheat and allowed them to sleep on the floor. He had several slaves. Ray assumed that he was a chief.

They stayed there for 11 days. The chief’s house was a spacious, barn-like structure, windowless and filthy. The nights were freezing, the crew’s khaki uniforms thin. To amuse themselves, the men would sit around a fire singing, a brief respite from the hunger and the cold. They belted the popular country ballad “I Saw Your Face in the Moon” until the Lolo villagers could sing along.

Early on, Sloan, the captain of the plane, showed up. He’d landed in a tree, several miles northeast of the others. But one crew member — the left gunner, a red-headed boy named Francis Reed — was still missing. With the chief’s permission, two crew members, accompanied by local guides, trekked to the plane wreck. They found the big aircraft in pieces — Lolo villagers already had scavenged its scrap metal and forged it into cooking pots and machetes. They also found Reed. He’d landed in a heap of twisted metal, minus his head, arm and a leg. They buried his body in the dirt and returned to the village.

One day, a large Lolo woman arrived, a turban wrapped around her head. Ray suspected that she was there to negotiate a transaction, and he worried about what that might mean. He decided to plan an exit.

He and Sloan agreed to aim for Yibin, a small city at the junction of the Yangtze and Yellow rivers, where American soldiers operated a weather station. If they followed rivers to the northeast, they figured, they would get there eventually. On the 11th day, the crew walked out. The chief put up some resistance — there were “a lot of violent threats and things like that,” Ray recalled. But he ultimately allowed them to leave.

The next few weeks unfolded like a fever dream. They walked for 250 miles, following the river. They endured burning heat, bitter cold, exhaustion, disease and hunger. They crossed a rushing river by rope. Ray survived two gun battles with bandits. He contracted dysentery and grew so weak that others had to carry him on a makeshift stretcher — just two bamboo poles, joined by fraying ropes. Death never seemed far off.

On their 27th day in Lololand, crew members reached a village called Anpienchang, then boarded a flat-bottomed boat and drifted along the river. For two days, they floated past crowds of villagers staring stone-faced from the banks. And finally, they reached Yibin.

Ray was exuberant. Sloan tracked down a phone and called the Army base in Chengdu. A night duty officer picked up, and Sloan told him that the crew was alive.

“Where are you now?” the officer said, sleepily.

“Yibin!” Sloan cried. “When are you going to send a plane to pick us up?”

“Soon as one’s available,” the officer replied. “Probably tomorrow. Take it easy.”

They were safe.

The police in Jinyang took me to a government compound, checked me into a bare-bones hotel and posted an official in the lobby to ensure that I wouldn’t leave. They scanned my documents and warned me against independent reporting. That night, I dined with propaganda officials in silence.

Early the next day, we loaded into two jeeps, drove onto muddy, cliffside roads, crossed a deep ravine and wound up on the opposite mountainside. About two hours later, we pulled into a village and parked in the courtyard of a dilapidated school.

The officials led me down a narrow path, until we came to a mud-brick house. There, an old woman squatted on a small concrete patio. She had silver hair and squinted through cataracts. She waved for us to come inside. Smoked meat hung from the ceiling, and chickens preened beneath her bed. The officials sat down on overturned beer crates and whispered among themselves.

The woman spoke in almost inaudible Yi, which her son, Bai Qugang, translated into Mandarin. Her name was Jiaba Yiniu, and she was 83 years old. Long ago, she said, a blue-eyed, blond-haired stranger wandered over the hills from neighboring Yunnan province. Her father, Shama Qubi — not her husband, as the officials had told me — took the stranger in. He stayed for seven years, grinding corn and looking after the village children. They called him “Latie”— a Yi word meaning brave. He didn’t speak much. Whenever planes passed, he’d look up at the sky. Gradually, he learned bits and pieces of their language, like “potato” and “Have you eaten?” When the Communists arrived in 1956, they took Latie away.

“His clothes were torn, so I made him new ones,” Jiaba said. “He liked me the best.”

Jiaba had no more information. She had no names, no photographs, nothing he’d left behind. Bai, her son, said that a white man traveled to the village in the early 1980s to thank Jiaba for looking after his father. But who was he? Nobody seemed to know.

Later, Bai changed his story. He said that he did not actually witness the meeting; he’d heard about it from a relative.

I realized that the story arose from a confluence of hearsay, like a decades-long game of telephone. Americans did fall from the sky. Yi villagers did surround them and wonder who (or what) they were. In a society with strong storytelling traditions but no written vernacular, the grapevine has extraordinary power.

Did Jiaba’s “slave,” in fact, exist? Six American planes crashed in Liangshan between 1944 and 1945, with 36 U.S. pilots onboard, according to local historians. One died — the B-29’s red-headed tail gunner, Reed — and the rest made it out safely.

But perhaps Jiaba’s slave crashed in Yunnan. Perhaps he was not an aviator, but one of the countless other Americans — mercenaries, bureaucrats, merchants — in southwest China during World War II. Perhaps he was British or Russian, or an albino member of China’s dominant ethnicity, the Han.

After meeting Jiaba, I interviewed two former high-ranking Jinyang officials, Qiu Qupo and Yang Hongqing. They grew up in the county, they said, and met Latie several times. They told his story the same way: He was kidnapped in Zhaotong, the small city in Yunnan province, bordering Liangshan. He was sold to a family clan called Shama. He had blond hair and blue eyes and learned to speak some Yi.

But their story ended differently. Soon after the People’s Liberation Army stormed Liangshan in the 1950s, it conducted a crude census. The soldiers tallied Liangshan’s aristocrats, its commoners, its slaves, its Lolos, its Han. One man, they discovered, was a challenge to categorize. He had light skin and spoke neither Lolo nor Chinese. They did not know what to do with him. They contacted the investigator, Shama Gupei.

The odds were not in the man’s favor. In the mid-1950s, the Communist Party — its memories of the Korean War still fresh — considered the U.S. an enemy. Authorities quickly determined that the man was an American spy and sent him to the Wupo iron mine, a high-altitude “reeducation through labor” camp in Liangshan’s Zhaojue County, which bordered Jinyang. The “spy” likely died there a few years later, according to Qiu, Yang and Shama.

After leaving Jinyang, I went to see an official in Zhaojue, and he drove me to the village of Wupo, a few miles from the county seat.

The official introduced me to the Wupo village chief, a gruff man in his mid-50s, and the chief led us into a dim concrete house. In the back, on a dusty bed, lay his 81-year-old father, Qumu Ali. I asked Qumu if he remembered the Wupo iron mine. He sat up. In the late ’50s, he said, the Communists built the prison mine in the village, behind a high wall. In 1963, officials relocated it, and he never saw it again.

“A lot of things were confidential,” he said. “Ordinary people wouldn’t know.”

The official smiled. “I told you there was nothing to see here,” he said.

My mind raced, but I had no reply. Perhaps I had reached a dead end: a lost pilot, an old woman’s story and a memory of a high wall. Or perhaps I had only scratched the surface.

In 1982, Garl Bud Ray’s daughter, Linda Potter, interviewed her father about his experience and recorded the conversation. Ray died on Feb. 5, 2011, at 92.

“This experience he had during the war was not just the highlight of his life,” Potter told me. “It was the only thing.”

In 2014, on a cool evening in Xichang, a Yi academic, Ma Linying, took me to dinner with two elderly Yi men and introduced them as the sons of late Yi clan leaders. We sat in a small garden, where the sun came down in slats through the latticework, and ate a dinner of potatoes, leafy greens and boiled chicken. Once, she explained, the two men were heirs to powerful family lines; then, during the Mao era, their fathers were killed or jailed, and their families cast into irrelevance.

One of the heirs told me that after the Americans bailed out over Liangshan, the Yi fashioned their parachutes into shirts. His uncle wore one for decades. They “thought that they came from the heavens, that they were magical,” he said. As he spoke, his eyes went wide, and the creases on his face deepened. “They thought that it was a gift from the gods.”

“You see how many Yi people have memories left from that crashed plane,” Ma told me. “Everyone knows about it.” The other heir nodded. He said that he met a foreigner when he was a small child in Jinyang. The foreigner visited many homes in the village, he said.

And the heir remembered one other thing: “He sang a song.”

Special correspondent Tommy Yang contributed to this report.

For more news from Asia, follow @JRKaiman on Twitter

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.