The CIA closed its original ‘black site’ years ago. But its legacy of torture lives on in Thailand

In February 2015, security forces in southern Thailand hauled in a 26-year-old Muslim man and demanded he confess to participating in a violent separatist insurgency. Officers tied him to a chair, covered his face with a shirt and poured water into his mouth until he choked.

It was one of dozens of torture cases documented by human rights groups in which Thais have been subjected to mock executions, held in painful “stress positions,” deprived of sleep or waterboarded.

The methods were introduced here in 2002 — by the CIA.

Thailand was home to the agency’s first secret prison, or “black site,” after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. There, American officers repeatedly waterboarded at least two high-profile detainees, part of the so-called enhanced interrogation techniques that much of the world would later describe as torture.

In all, 10 CIA prisoners were arrested or held on Thai soil before being transferred without due process to the U.S. military prison at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba or to other countries, according to a 2013 report by the Open Society Justice Initiative, which has studied the detention program.

That dark chapter in CIA history has reemerged with President Trump’s nomination of a new director, Gina Haspel, a career undercover officer who oversaw the Thai black site in late 2002. At her confirmation hearing, which is scheduled for May 9, Haspel will face sharp questions from senators who argue that the tactics failed to extract useful intelligence and damaged U.S. standing in the world.

But in Thailand, collaboration with the CIA ushered in an era of impunity for security forces, according to rights advocates, who accuse the army and police of adopting the agency’s most extreme methods to punish Muslim separatists and other dissidents.

“The legacy of the CIA secret prison is a daily reality in Thailand today,” said Sunai Phasuk, a Bangkok-based researcher with Human Rights Watch.

“Every week we have a new case of torture, and the tactics are very similar to what we learned about what the CIA did. These are seen as effective tools. We had never heard of waterboarding before — it was only after 2004 or 2005 that it’s been used here.”

The legacy of the CIA secret prison is a daily reality in Thailand today.

— Sunai Phasuk, Human Rights Watch

There has never been an investigation into the Thai officials or agencies involved in the CIA’s covert detentions, which continued until at least 2004 and probably violated national laws.

Successive Thai governments have denied there was a black site. The military leadership that has ruled the country since 2014 includes generals who might have known about or signed off on it, while the political opposition includes supporters of the prime minister at the time, Thaksin Shinawatra, who now lives in exile.

“The existence of a U.S. black site is one of Thailand’s worst kept secrets,” said Andrea Giorgetta, Asia director for the International Federation for Human Rights, in Paris. “It is unlikely to be an issue that will resurface here because nobody would benefit from bringing it up.”

Thailand is far from alone in failing to examine its role in the CIA program, which allowed terrorism suspects to be interrogated without any of the standard U.S. legal protections. Of 54 countries that Open Society identified as having captured, held, questioned, tortured or helped transport CIA detainees, fewer than half have opened domestic inquiries or heard court cases challenging their involvement.

Panitan Wattanayagorn, a political scientist and advisor to Thailand’s deputy prime minister on security affairs, said that many Thais endorsed the army’s tough measures, particularly against insurgents, and that officials who would have been aware of the black site had faded from public view.

“It has been a long time,” he said. “The case doesn’t intrigue the public anymore unless there is new evidence — and that would have to come from the United States.”

::

Even the prison’s location remains cloaked in mystery.

Many experts believe it was situated at a former U.S. intelligence post in the remote northeastern province of Udon Thani. Some say it was at an air base southeast of Bangkok that U.S. forces have used as a refueling hub for flights into Afghanistan. Still others point to a section of Bangkok’s Don Mueang International Airport controlled by the Thai air force.

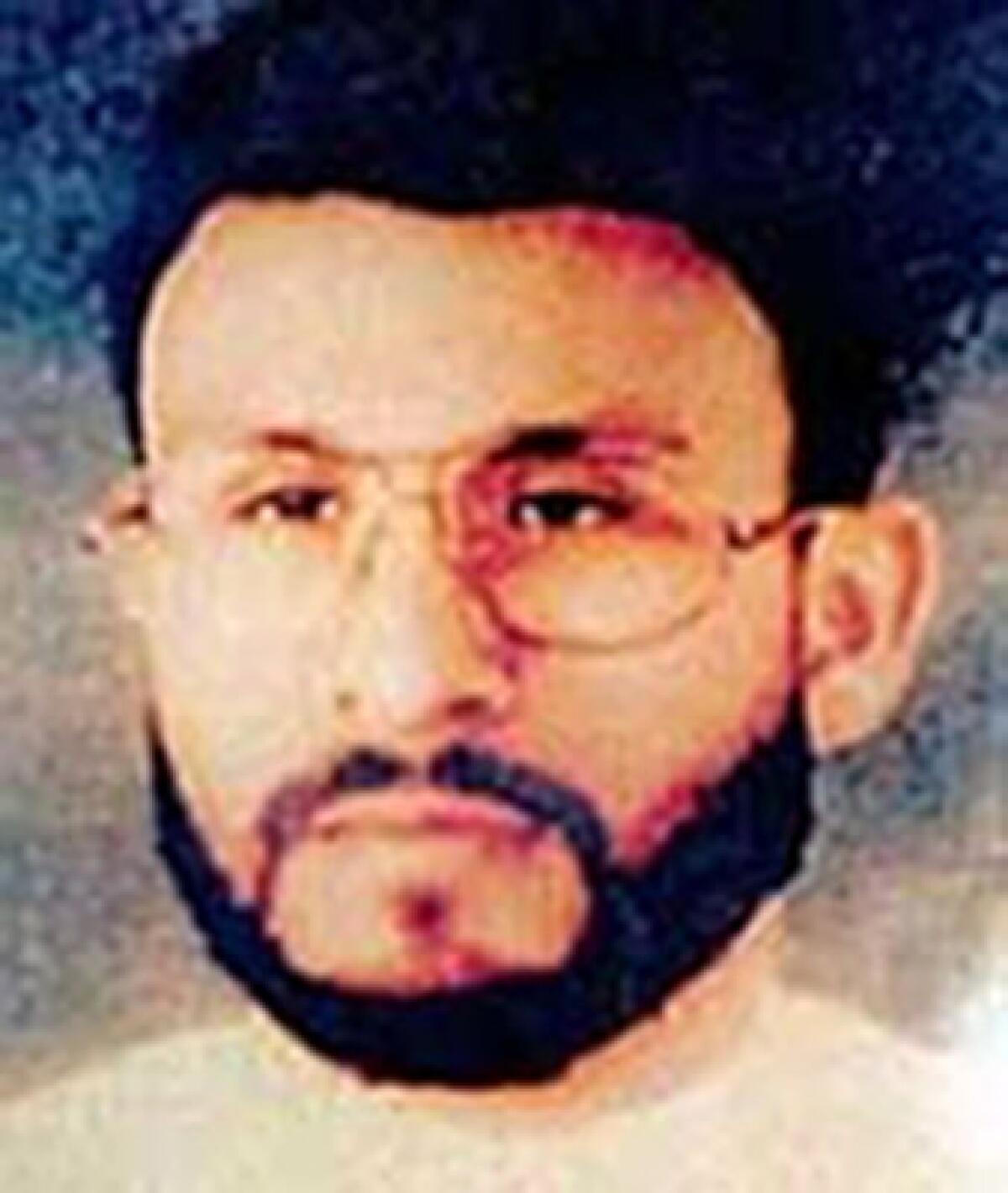

What is known is that the black site was established to hold Abu Zubaydah, a Palestinian who was considered an Al Qaeda suspect when he was captured in Pakistan in March 2002.

The agency wanted a facility where “the comings and goings of agency officers and their ‘guests’ would not easily attract attention,” wrote Jose Rodriguez, who ran the counter-terrorism center at CIA headquarters and detailed some of the history of black sites in a 2012 book, “Hard Measures.”

Thailand, which was already operating a joint intelligence center with the U.S., agreed to help.

“To our potential hosts we promised three things: our gratitude, a sizable amount of money and our assurances that we would do everything in our power to keep their support secret,” wrote Rodriguez, who didn’t identify the country in his book.

At a facility code-named Detention Site Green, Abu Zubaydah was kept in a white, windowless cell illuminated by four halogen lamps, according to a 499-page, partially redacted summary of the detention program that the Senate Intelligence Committee released in 2014. He was typically interrogated while naked and shackled to a chair after being kept awake for hours.

The first CIA prisoner to undergo the enhanced measures, he was slammed against a wall, stuffed into a coffin-like box and waterboarded — strapped to a gurney as water was poured over his face to simulate drowning — 83 times, often to the point of vomiting, the report said.

“Thailand was the test case,” said Benjamin Zawacki, author of a recent book on U.S.-Thai relations. “It was the first place where the CIA applied their techniques without constraints on a foreign national.”

The Senate report concluded that the techniques didn’t elicit any useful information from Abu Zubaydah. He was eventually transferred to Guantanamo Bay, where he remains.

But at the time, his interrogators judged “the aggressive phase” in Thailand a success, the Senate report found. They wrote to CIA headquarters that it “should be used as a template for future interrogation of high-value captives.”

::

Haspel reportedly arrived in Thailand after Abu Zubaydah’s interrogations and ran the site during the questioning of another Al Qaeda suspect, Abd al Rahim al Nashiri, a Saudi national thought to be involved in the 2000 bombing of the U.S. destroyer Cole.

Nashiri was imprisoned in Thailand for about a month and waterboarded at least three times, the Senate report said. James Mitchell, one of the psychologists who helped develop the interrogation program, recalled that Nashiri’s small frame made it difficult to keep him strapped down.

“When the guards stood the gurney up on end so that he could clear his sinuses, Nashiri would slide down, and his arms and hands would almost slip out from under the wide Velcro bands designed to hold him in place,” Mitchell wrote in his 2016 book, “Enhanced Interrogation.”

When CIA officials worried the location of the black site had leaked to U.S. media — and that too many Thai officials were also in on the secret — they closed it down in December 2002. Nashiri was moved to a CIA facility in another country and is currently awaiting military trial at Guantanamo Bay.

Three years later, at the urging of Haspel and others, the agency destroyed 92 tapes of the interrogations that were stored at the CIA station in Bangkok.

Amid the renewed controversy over Haspel’s background, her colleagues are gearing up to defend her record. On Friday, the CIA released a declassified 2011 memo saying the agency found "no fault" in Haspel's role in the destruction of the tapes.

“Through the confirmation process, the American public will get to know Ms. Haspel for the first time,” said Jonathan Liu, a CIA spokesman. “When they do, we are confident America will be proud to have her as the next CIA director.”

::

It is unclear when Thailand’s prime minister learned of the prison. In November 2005, when the Washington Post broke the story, Thaksin issued heated denials and briefly threatened to sue the newspaper, according to a leaked State Department cable.

He and his aides continue to deny prior knowledge of the black site. But for several years, the telecommunications-tycoon-turned-politician secured concessions from President George W. Bush for supporting the U.S.-declared war on terrorism.

In June 2003, just before he traveled to Washington to meet Bush, Thaksin signed an agreement not to extradite Americans accused of war crimes to the International Criminal Court. His government also granted itself sweeping powers to detain terrorism suspects in what critics likened to a Thai version of the USA Patriot Act.

Shortly afterward, U.S. and Thai personnel captured Riduan Isamuddin, an Indonesian Al Qaeda suspect better known as Hambali, outside Bangkok. Over several days, CIA officers kept Hambali naked, held him in stress positions and deprived him of solid food, according to the Open Society report. He is currently imprisoned at Guantanamo Bay.

That October, when Bush was in Bangkok for a regional summit, he praised Thai forces for “ending [Hambali’s] lethal career.”

Two months later, the Bush administration upgraded Thailand to the status of a major non-NATO ally, allowing the Thai military to purchase U.S. weapons at reduced prices.

In return, the U.S. offered only muted criticism as Thaksin amassed power, unleashed a bloody drug war that left thousands dead and imposed a state of emergency to quell separatist unrest. The army overthrew Thaksin in 2006, accusing him of corruption, but has continued to use harsh tactics against civilians in the south under military leader Prayuth Chan-ocha.

“We are living with the effects of the U.S. cooperation,” said Pornpen Khongkachonkiet, director of the Cross Cultural Foundation, an advocacy group that produced a 2016 report on torture by soldiers and paramilitary groups in southern Thailand.

The report documented 54 torture cases, many of which included intense psychological abuse that seemed designed to create a sense of helplessness. Although it’s unclear whether any Thai personnel were present during CIA interrogations, Pornpen said local interrogators appear to have adopted some of the severest U.S. tactics.

A 41-year-old man said he was made to stand naked on one leg in extremely low temperatures. A 36-year-old was force-fed water until he passed out. Several detainees said they were prevented from sleeping and warned they would be killed if they didn’t confess to crimes.

Instead of investigating the claims, the army filed a criminal defamation suit against Pornpen and two colleagues. The charges were later dropped, but Pornpen said threats of official retaliation keep victims from speaking out.

The fears appear to be well founded. In 2004, Somchai Neelapaijit, a human rights lawyer representing five men who said police tortured them into falsely confessing to an attack, went missing and was never found.

Five police officers accused in Somchai’s disappearance were acquitted. In 2011, one of his clients was convicted of making false statements about his alleged torture and sentenced to two years in prison.

::

Few Thais have attempted to pierce the secrecy surrounding the CIA detentions.

Sunai, the human rights researcher, was working as a legislative aide when the black site was disclosed and recalled that opposition lawmakers filed a parliamentary motion to force Thaksin and senior Cabinet members to answer questions.

“They refused to respond and that was it,” Sunai said. “There’s no penalty to refuse. And it was the only time anyone tried to start an inquiry.”

Some time later, Kraisak Choonhavan, then the chairman of the Thai Senate’s foreign affairs committee, was approached by American lawyers representing a Libyan couple who were detained in Bangkok in 2004. The woman, who was six months pregnant, “was bound, gagged and photographed naked as several American intelligence officers watched,” according to a letter that Sen. John McCain sent to Haspel last month posing questions about her role in the detentions.

Kraisak relayed questions to contacts in the Thai intelligence community.

“Nobody knew anything,” he said. “That meant to me that it was strictly a CIA operation.”

Now 70 and ailing from throat cancer, Kraisak said Haspel’s nomination probably represents his last chance to learn more about what the CIA did in Thailand.

“For most people, this is a non-issue. Why? Because in Thailand, torture by officers is common,” he said. “But I am truly ashamed at my country for allowing this to happen.”

Bengali reported from Bangkok and Megerian from Washington.

Shashank Bengali is The Times’ South Asia correspondent. Follow him on Twitter at @SBengali

Twitter: @ChrisMegerian

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.