PALMAS ALTAS, Mexico — Like many Mexicans in the United States, María Avila worked for decades north of the border with a simple dream: to one day return home.

She toiled at a Palm Springs country club by day, served meals to wealthy clients at night and cleaned houses and mended clothes on the weekend, slowly saving to build a home of her own back in Juanchorrey, the wind-swept pueblo high in the mountains in Zacatecas state where she grew up.

With five bedrooms, a Jacuzzi and a grand entryway capped by a cupola, the hacienda stood out from the crumbling adobe buildings nearby. Avila, 60, and her husband filled the yard with blooming fruit trees. After a lifetime of labor, they were finally making plans to retire there.

Then in 2020, narcos invaded Juanchorrey.

Within months, the sleepy rancho famous for its fluffy tortillas and a long history of sending migrants to the U.S. had been overtaken by gangs who robbed, killed and kidnapped with abandon.

When a horrific act of violence touched a member of Avila’s own family, her children begged her not to return.

“For me, that’s a no,” her youngest daughter, Andy Preciado, 34, told her mother. “I’m terrified of you going.”

Avila longed for Mexico — for the predawn crow of roosters, the salty taste of local cheeses, the languid afternoons in the plaza with friends. But as she wrote impassioned letters to Mexican leaders pleading for the military to intervene in Juanchorrey, she and her husband, Abraham, began contemplating a very different future.

With some $350,000 tied up in the house in Mexico, retiring in California would be tricky. The couple was still paying off their home in Cathedral City, a working-class suburb of Palm Springs, and figured they’d probably have to sell it and move into a trailer.

As violence engulfs large swaths of Mexico, similar calculations are playing out across the United States, where some 39 million people of Mexican origin reside.

Migrants from particularly dangerous regions are being forced to reevaluate their ties to their home country, with some deciding that returning is not worth the risk.

Los Ángeles Azules have been making music for four decades. The Mexican band’s songs bring people together.

It’s a phenomenon that experts say could have profound economic and cultural consequences — reducing the flow of dollars into parts of Mexico that have long depended on them and straining connections between migrants and their homelands.

For Avila, who helps lead a federation of Zacatecan migrant groups that over decades has raised tens of millions of dollars for public work projects back home, the whole thing stung of betrayal. She had given so much to Mexico — and this was how she was being repaid?

“I’ve cried, I’ve prayed, what else can I do?” she said. “My dreams have been thwarted.”

::

For many years, Zacatecas was poor — but peaceful.

As a kid, Avila would roam the countryside with her friends, exploring hidden caves and swimming in icy rivers. At night, cicadas buzzed and fireflies lit up the sky.

But when drought hit, and the cornfields dried up, people went hungry. Many left in search of work, including Avila’s father, who moved to California to pick produce as part of the Bracero migrant labor program in the early 1960s. At 18, Avila followed him north and eventually settled in the rapidly growing Coachella Valley.

Leaving felt like the only way to get ahead, she said. “If you stayed, you could work your whole life and never make enough to buy land, much less build a house.”

In California, Avila and her first husband worked so much that their children complained they barely saw them. The kids would catch up with their mother when they could, telling her about their days as she changed clothes before running out for a second or third shift.

But in the summers, when the heat arrived and work slowed, Avila and her family would caravan 25 hours by car down to Juanchorrey, often towing a trailer stuffed with construction materials for their dream home.

A third of all people born in Zacatecas live in the U.S., according to the Mexican government, with California the center of the diaspora. But as long as migrants had been leaving the state, they had also been coming back.

During holidays — such as the famed Easter celebration in Jerez, a colonial-era city near Juanchorrey — migrants would flood the streets, easily distinguishable in their new jeans and shiny boots, spending big on food and drink and mariachis.

Column: In Mexico stands a lonely monument for a fallen L.A. politician: ‘el licenciado Jose Huizar’

José Huizar was once held up in political circles as a bootstrap success story. He now serves as a cautionary tale about the perils of power.

The migrants raised money in the U.S. to pave roads, repair churches and build baseball fields in their hometowns. They opened corner stores and car dealerships and built sprawling homes with gabled roofs, ornate columns and other architectural touches imported from north of the border. They bought so much land that real estate prices began to be set in dollars.

In Juanchorrey, Avila’s kids — all born in the U.S. — spent their summers getting to know their relatives and local foods. With no cellphone service, they entertained themselves, organizing footraces and dances. To celebrate Andy’s quinceañera, the family slaughtered a cow and eight pigs and fed more than 3,000 guests.

“I used to feel safer out there than I did here,” said Avila’s youngest son, José Preciado, 35. “We never locked the doors — the only thing we closed was the gate to keep the cows out of the yard.”

“That doesn’t exist anymore,” his mother said. “There aren’t even any cows left. There’s nobody left to take care of them.”

::

There was once life in these hills.

That’s what Benjamín Carrillo thought as he cut across an empty landscape near the little town of Palmas Altas, his old Jeep a speck of white inching across a vast expanse of yellow grass.

Up until a few years ago, children played in yards here and farm animals grazed in the fields. Peaches ripened on orderly rows of trees.

But now Palmas Altas, like Juanchorrey, about 40 miles south, felt like a ghost town.

As a young man, Carrillo, 44, worked construction in the U.S. to save up money to open a mechanic shop back home. He was at the shop two years ago when a group of strange men showed up.

As Carrillo changed the tires on their trucks, the men told him that they were engineers who had come to repair a nearby road. But soon it was clear that they were gang members who had come to seize control of the land.

It’s not just drugs. Mexico’s cartels are fighting over avocados.

For years, the Sinaloa cartel claimed the drug routes that pass through Zacatecas. Its members largely kept to themselves — and seemed to keep the peace. Zacatecas was long considered one of the safest states in central Mexico.

But then the Zeta gang and later the Jalisco New Generation cartel started muscling in. The new groups had a different modus operandi: They had no qualms about kidnapping residents or extorting money from shop keepers.

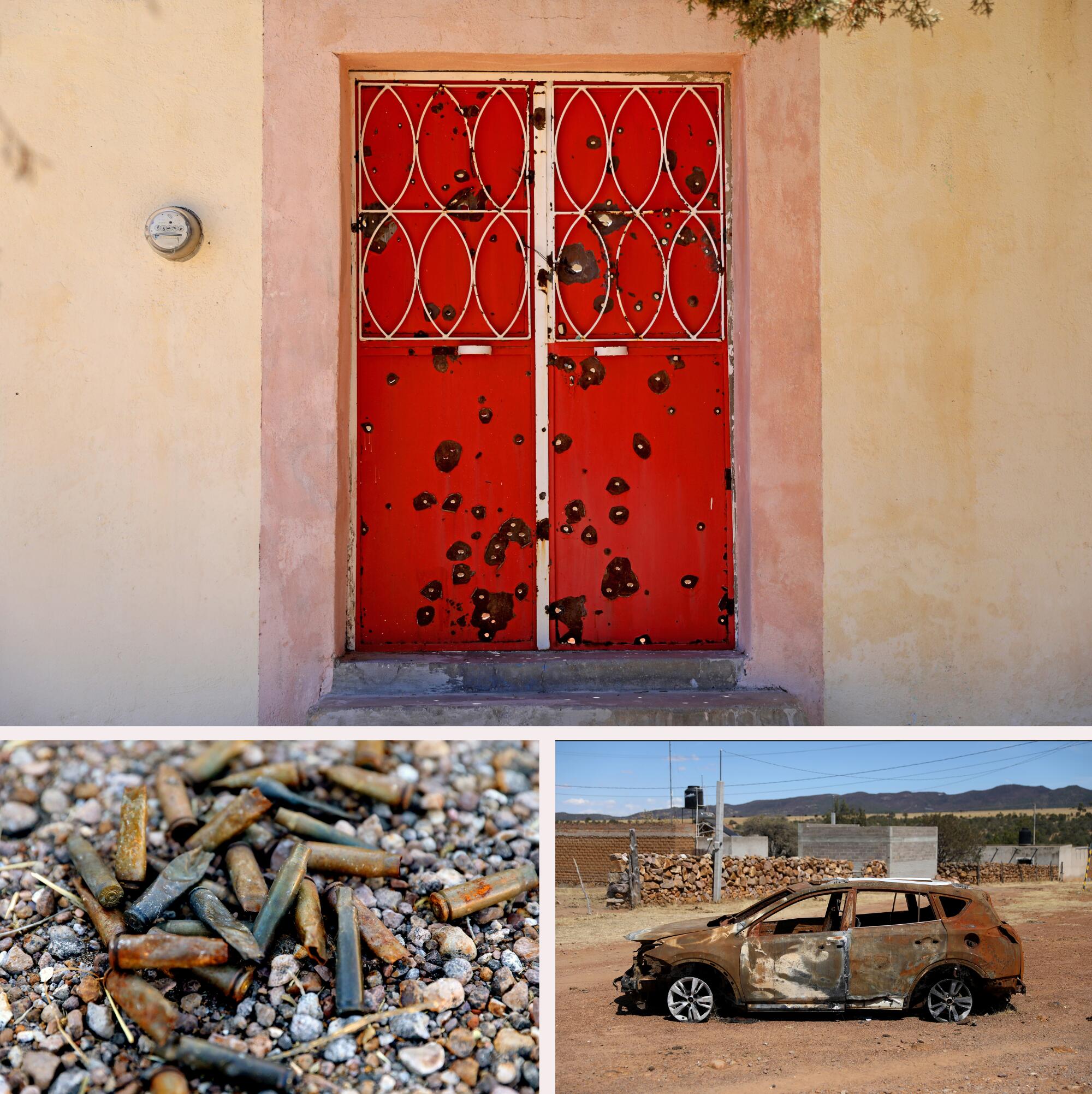

As the two groups battled, violence exploded across the state, with homicides soaring 323% between 2015 and 2022.

In Palmas Altas, young men began disappearing, forcibly recruited for cartel warfare. Gang members broke into houses and stole everything of value. When several neighbors were hauled away at gunpoint, Carrillo, his wife and their two young children fled.

They joined his wife’s family in Fremont, Calif., where Carrillo, who has a tourist visa but not a work permit, washed dishes at a restaurant for under-the-table pay. They monitored the situation back home via WhatsApp groups, where the region’s few remaining residents reported gun battles in the streets and even in the local cemetery.

Over the strong objections of his family members, most of whom live in Texas, Carrillo decided to come back late last year. Federal troops had entered Palmas Altas, setting up a temporary base at a local school, and many gang members had fled. Carrillo knew it was risky — but also knew he wasn’t cut out for washing dishes.

He and his family are among about 100 residents who live in the town now, down from 350 before the gang takeover. There is little work for a mechanic, so Carrillo spends much of his time in the countryside, growing beans, corn and peaches and keeping watch over the homes of people who live in the U.S.

In a village called Juana González, he parked his Jeep in front of a recently constructed house and pushed open the broken front door.

Elegant chandeliers hung from the arched ceiling and pretty blue tiles covered the kitchen. But beer cans and food scraps littered the floor. Drawers hung open, cleared of valuables except for a handful of family snapshots and Christmas cards. The stove, the refrigerator and several televisions had been ripped from the walls and hauled away.

At the home next door it was a nearly identical scene, with one exception. “They didn’t ransack this one quite as hard,” Carrillo said, his boots crunching through broken glass. “At least they left the mattresses.”

The owners of the homes are two brothers who grew up in Juana González and left when they were young to find work in California. They intended to retire here. But the men haven’t returned since cartel members moved into the houses, scrawled gang affiliations on the furniture and last year killed a third brother who lived across the street. The brothers agreed for their stories to be shared but asked not to be named out of fear.

“How can they come back?” Carrillo asked. “Their dream has disappeared.”

::

In Juanchorrey, things were just as bad.

Gang members seized homes and vehicles. They imposed a curfew and patrolled the streets in bullet-proof trucks.

Locals seemed left with one choice, Avila said: “You run. And if you don’t, they kill you.”

But a few people held out. One of them was the brother of Avila’s husband.

He was staying at the couple’s hacienda last fall when an intruder dressed in a ski mask attacked him with a crowbar, tied him up with a cable and stole a safe filled with money and important documents.

In California, the family felt anguish — and impotence.

“There’s no one to protect you,” said Avila’s husband. “We’re like sheep. The wolves come and slaughter us, and there’s nothing you can do about it.”

American tourists and remote workers are gentrifying some of Mexico City’s most treasured neighborhoods. Backlash is growing.

At birthdays, weddings and other gatherings north of the border, migrants discussed the situation back home in hushed voices, trading news of other atrocities in Zacatecas that had touched people with ties to the U.S.

In January, authorities in Jerez found the body of a 36-year-old Ohio architect who had disappeared along with his fiancée on Christmas Day.

In May, a 20-year-old Oklahoma man was abducted, tortured and killed while on a trip to visit his grandparents in the municipality of Valparaíso.

Last year, a 57-year-old Mexican American woman was killed when gang members robbed the house where she was staying in southern Zacatecas.

“Today practically no one wants to come back,” said Rodolfo García Zamora, an economist who has studied migration for three decades at the Autonomous University of Zacatecas. Most of García’s own relatives in the U.S. who used to return to Zacatecas during holidays now prefer to stay in California or Texas, he said.

He doesn’t blame the migrants, whose public cries for help about violence in their home communities have largely gone unanswered.

“The government appears to have no interest and no capacity to confront this tragic situation,” García said. “The message that these communities and our family members are receiving is: The future is in the United States.”

It’s not just drugs. Mexico’s cartels are fighting over avocados.

The bloodshed is emptying out rural Mexican towns that had already been drained by migration, he said, and it threatens to cut off a critical source of the state’s economy. Last year, migrants sent $1.7 billion in remittances to the state — almost as much as the entire Zacatecas annual budget.

The violence is also threatening investments migrants have already made.

Four decades ago, California migrant groups pioneered a program in which local, state and federal governments in Mexico matched donations raised by migrants in the U.S. for their home communities. But those projects have mostly stalled, in part because Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador cut federal funding for the program, and in part because of violence.

“In order for there to be development we need to feel safe,” said Lupe Gómez, who leads a federation of civic groups in Southern California that funds development projects in Zacatecas. Avila is the group’s secretary.

Gomez, who was 14 when he left Mexico to pick celery in Seal Beach, still goes back to Zacatecas to visit his 92-year-old mother near the town of Jalpa. But he makes a point to not drive a flashy car or build additions to his family’s house that might attract unwanted attention.

“It’s like you’re inviting the bad guys to kidnap you,” he said. “You can’t shine in Mexico.”

Goméz isn’t only worried about the development his state will miss out on if migrants choose not to return. He’s also worried about lost connections between migrants, their families and their heritage.

“I worry about people not wanting to bring their children here,” he said on a recent hot morning as he walked the streets of his hometown, greeting the few neighbors who remained. “I worry about the kids of migrants not knowing their roots.”

::

On Mother’s Day, Avila’s home in a quiet Cathedral City subdivision filled with the smell of sizzling chiles rellenos. She had cooked them using some of the cheese that she had brought back frozen in a cooler the last time she visited Juanchorrey, in 2019.

As her children arrived, bearing champagne for mimosas and a platter of fresh-cut fruit, Avila greeted them with kisses and heaping plates of food.

The kids have built busy lives in the U.S.

Karina Quintanilla, 44, is the mayor pro tempore of the nearby town of Palm Desert. Armando Preciado, 38, is a mechanic for Tesla. José works as a contractor with the Department of Homeland Security. Andy is a nurse.

Yet at gatherings like these, where the kids often speak in English and their mother answers them in Spanish, conversations often veer back to Mexico.

As they ate, they passed around a video circulating online that showed cartel members toting semiautomatic rifles on the streets of Juanchorrey, and another that appeared to show a group of narcos celebrating with town officials during the annual Easter celebration in Jerez.

“They’re just kids,” Avila remarked, of the gang members. There was a part of her that could empathize with the young men, she said. She too knew what it meant to grow up poor in a place with few opportunities.

A few weeks earlier, there had been hopeful news out of Juanchorrey.

“Thanks to our pressure, the army showed up,” Avila said. “Now some people are returning.”

“That’s great!” said Karina.

“Oh, they come every now and then,” said Avila’s husband.

“But then they disappear,” Avila said.

Even with the army’s presence, violence is common. This month, the tortured bodies of four men were dumped along a highway not far from Juanchorrey.

Still, Avila held out hope that at some point she could return for a short visit just to check on the house and salvage a few prized possessions.

Her daughter Andy hated the idea. Her son Armando was more open. “If that’s your happy place, I can’t tell you not to go,” he said.

Despite strict gun laws, Mexico is in the grips of an arms race.

José, a former U.S. soldier who deployed to Afghanistan and dreams of an American military intervention in Mexico to stop the drug violence, said he didn’t want his mom going back without him. “If I’m going to go, it’s not for vacation,” he said. “I’m going to go on alert. I’m gonna be on guard protecting her.”

“Let’s do it,” Avila said with a conspiratorial laugh. “Let’s go right now!”

The kids recalled long, happy summers in Juanchorrey. They remembered how the adobe buildings smelled sweet after monsoon rains. How the fireflies lit up the night. How you could wander into the home of a friend or relative and always be invited for a meal.

Andy said she worried that she was forgetting the flavor of the rancho’s famous mole. She worried that she was losing her Spanish slang too. And she worried that her young son might never get to know where his grandmother came from.

She sees herself as both Mexican and American, and said the recent violence had stirred new conflicts inside. “It makes me sad that I can’t go to my mom’s country because of American guns and American drug consumption,” she said.

“It makes me sad to see that my mom’s retirement plan is gone,” she said. “All of her blood, sweat and tears — all of her lost time with her kids on Christmas and birthdays — it was for nothing?”

Avila doesn’t know how her story will end. She dreams of being buried in Juanchorrey, but knows that she might have to go with the backup plan that Karina devised: Be cremated, with her ashes placed in an urn that would rotate among her children throughout the year.

She said she had learned throughout this difficult process that nothing — no house, no future plan — mattered more than her family’s safety.

“I would rather think that we lost everything we built than lose our lives,” she said.

Cecilia Sánchez Vidal in The Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.