How Palm Springs ran out Black and Latino families to build a fantasy for rich, white people

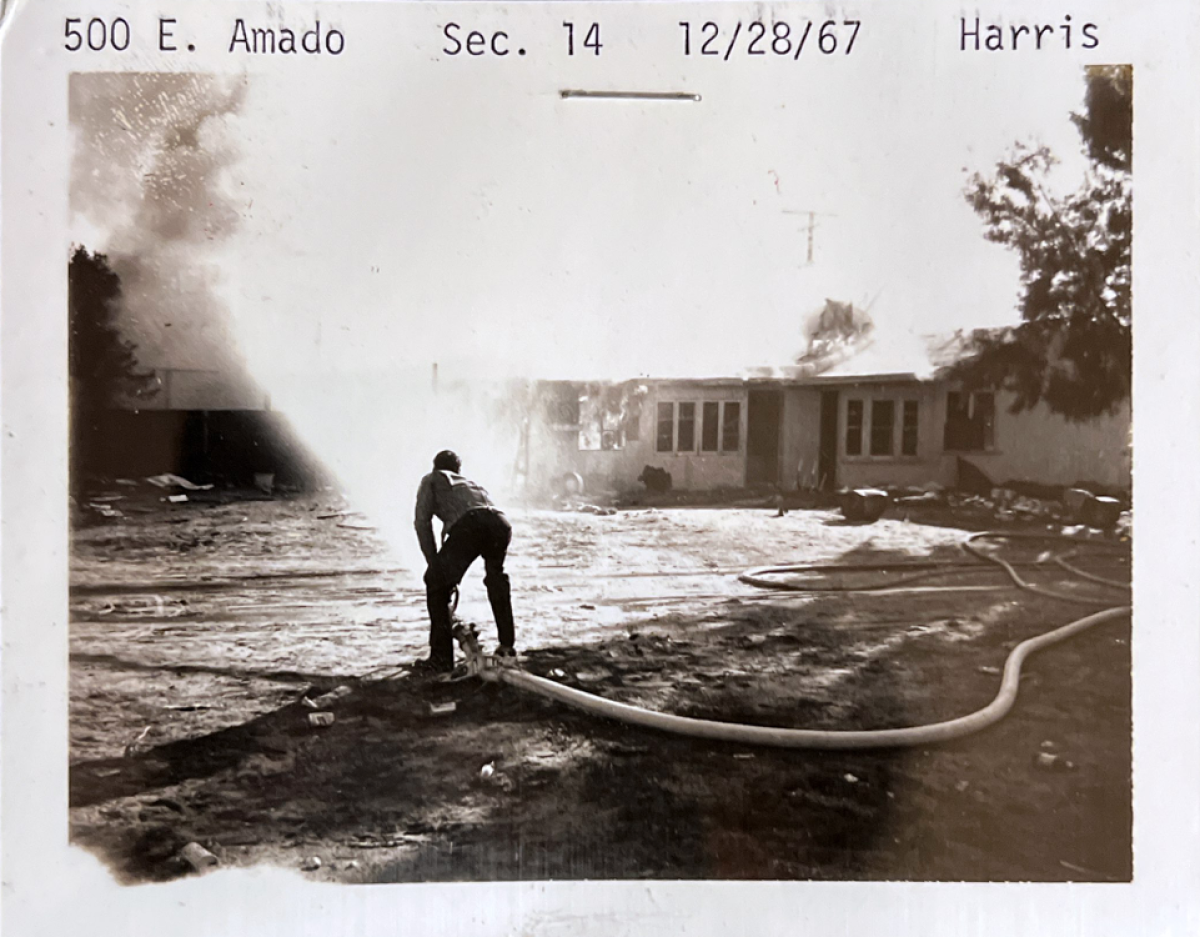

At first, Joe Abner would come home from school and find a single house on fire. A vacant house, toppled by a bulldozer and set ablaze by Palm Springs city firemen.

Then two houses would be burning.

”Then it got to the point when you saw smoke, you were pretty well freaked out because you didn’t know if it was your house or one of your neighbors’ houses,” Abner said. “They were tearing houses down right in front of your face.”

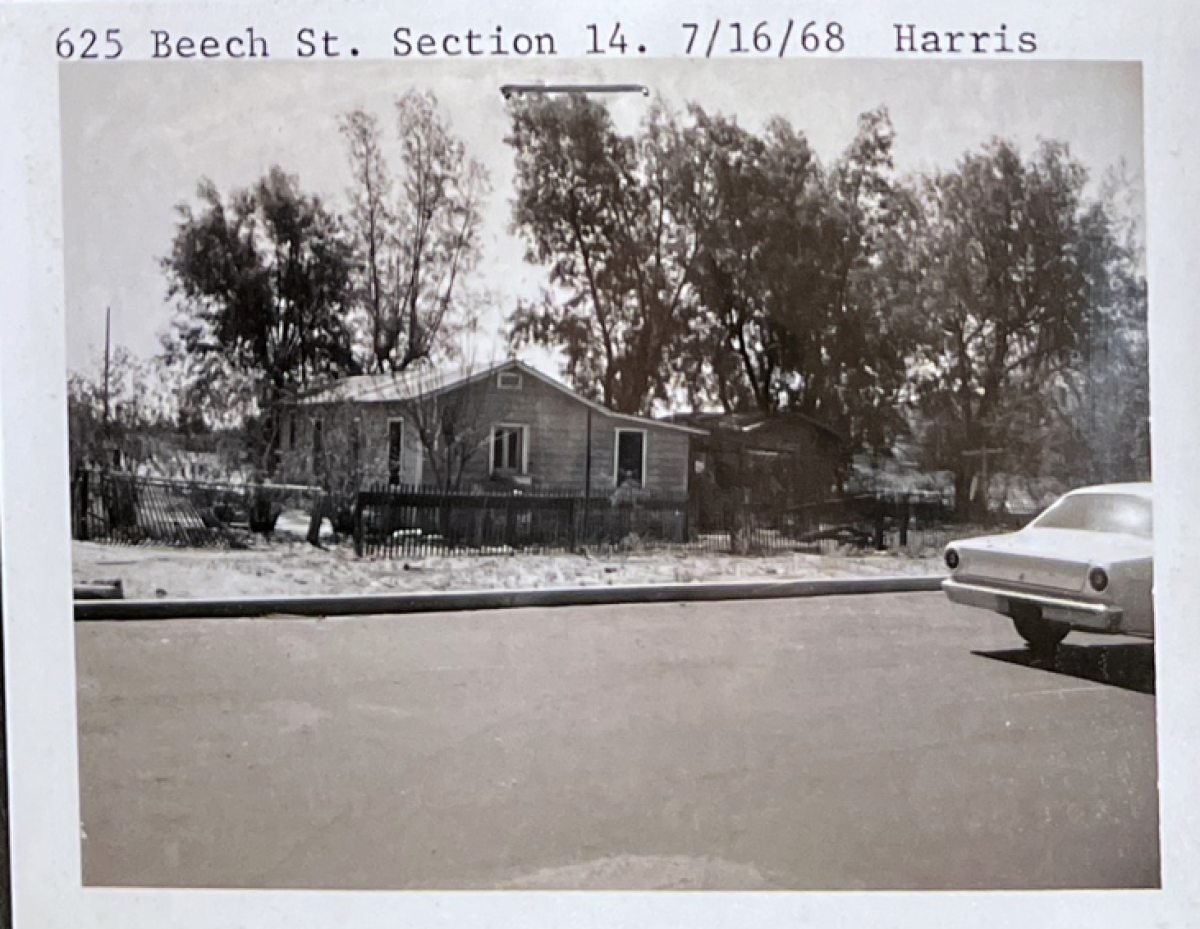

Now 72, Abner was 13 when his family fled Section 14 in Palm Springs, leaving the home his father had largely built by hand to be razed and turned to soot. In the name of “slum clearance,” officials in the 1950s and 1960s ran Black families like Abner’s as well as Latinos out of prime downtown land, without proper notice or relocation aid, and burned down their homes to clear a path for hotels and shops.

Palm Springs was being sold as a fantasy playground for the rich and famous, but as former Section 14 resident Pearl Devers points out, “We were not part of the vision.”

A 1968 state investigation concluded that the clearance was a “city-engineered holocaust.”

The razing of a multiethnic community may strike some as a relic of a time when Black, Latino and Asian people throughout California and the nation faced systematic housing discrimination. But the displaced Palm Springs families say the racism that drove the burnouts lingers, and they are fighting for reparations from the city.

Beneath Palm Springs’ mystique lie layers of troubled history, stacked up to form a segregated geography that survives today.

The families are still sifting through that buried strata, through the memories and what-ifs.

Delia Ruiz Taylor, 71, sat on a cracked concrete slab, remnants of a Section 14 structure, and pointed across the sand and creosote bushes to where her family had lived, where she and friends had played stickball, dodgeball and tag.

“We used to go to the Village Theatre and sit on the balcony,” she said. “We kids loved it.”

She later learned why they sat upstairs: The floor seats were for whites only.

“Do you know how hurtful that is to hear?” she asked.

Every payday, Ruiz’s father would bring home construction supplies from the store where he worked to build their three-bedroom home.

The family’s presence on Section 14 stemmed from a historical quirk when the railroads crossed the frontier. The federal government divided land that the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians had used for hundreds of years into square-mile tracts. Even-numbered sections went to the tribe and odd ones to the railroad, which sold them to lure workers and settlers West.

The Agua Caliente Band and its members owned 6,700 acres in Palm Springs, but none so potentially valuable as Section 14, just east of the city’s glittering “village” center. Through the first half of the 20th century, the federal government, which held the Indian land in trust, barred tribal members from issuing leases of more than five years. This stymied major development.

Into the breach came working-class families — Latino, Black, Indigenous, Filipino and white — that rented small plots on Section 14, one of the few areas where nonwhite people could afford or were allowed to live. They put up shacks, wood-frame and concrete-block houses, churches, a cafe and a driving range, and worked in Palm Springs as gardeners, bricklayers, hotel maids and housekeepers.

In 1959, when the federal government began allowing longer leases, eventually up to 99 years, developers came calling. Section 14 residents, most of them barred from living in much of the city by racial deed restrictions and lending discrimination, were forced to scatter to desolate housing tracts on its outskirts, or make long commutes from decidedly less glamorous towns — Indio, Beaumont, West Garnet.

Ruiz and her family lost their home in the burnings and moved to Cathedral City, where children spat racist taunts at her and the white family next door refused to talk to them.

“We were the second or third Mexican family there,” Ruiz said. “Within a year or two there were no more white people there.”

Ruiz’s husband, Alvin Taylor, sat quietly next to her as she spoke; he can’t spend much time in Section 14 without crying.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Like many former residents, Taylor, 70, remembers it as a quiet, close-knit community that they knew as the Reservation, where kids dashed in and out of one another’s homes or roamed the desert for adventure.

Taylor was 8 when his family fled the burnouts. He, his two siblings and their mother doubled up with another Section 14 family, then skipped from place to place.

“We moved to the next place and the next place, five, six or seven times,” said Devers, his sister. “We were running from getting burned out.”

Their father, a carpenter, music promoter and local National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People leader, had stayed behind, frantically searching for land or a loan so he could move his house, to no avail.

Fortune came calling a few years later for the younger Taylor, who played drums. While working as a busboy at the Palm Springs Biltmore, he was invited to sit in for the hotel band’s drummer, who’d had too much to drink.

Little Richard, who walked in with Frank Sinatra and Sammy Davis Jr., said he hadn’t heard drumming like Taylor’s since his childhood in Georgia. Taylor was only 14, but Little Richard persuaded his mom to let him go on tour.

Taylor would move to Los Angeles and perform, record and produce music with other icons such as Elton John, George Harrison and Bill Withers.

Dozens of gold and platinum records later, he returned to the desert and married Ruiz, a childhood acquaintance. Then, the pain of expulsion from the Reservation bubbled back up.

“I’ll never forget the cowardice of the act of our family being displaced, herded off like cattle and sheep, having to move from house to house,” Taylor said.

Devers, 72, who married another Section 14 resident, moved to Sherman Oaks and worked her way up from a secretary at ABC to production coordinator before leaving to oversee the red carpet and media at the Oscars. After escorting Rosa Parks to one of the ceremonies, she went to work for the civil rights icon, and eventually produced “The Rosa Parks Story,” a CBS movie starring Angela Bassett.

Devers’ house is full of entertainment and Oscar memorabilia, including a photo of her late husband walking the red carpet, against her explicit instructions. She’s done well. But she knows that other people, including her father, were shattered by the bulldozings and burnouts.

“He just drank himself to death,” she said. “He was a real hard worker, a good provider. It was just really hard to watch him go down like that because he couldn’t provide for his family.”

Other families fled Palm Springs before they were cornered.

“I remember my mom saying, ‘We’ve got to get out of here,’” said Patricia Henderson, 75.

A bank about 25 miles west in Banning, unlike those in Palm Springs, would lend Black people money, and financed her family building a home there. The family would return to Section 14 on Sundays to worship at New Bethel Church of God in Christ.

Later, she said, the church “had to get up and get out too. ”

Living in Section 14 was “the best time of my life,” Henderson said. “We had a bond with people that lasted until we died.”

Joe Abner remembers Section 14 as a magical idyll of hiking with friends into the San Jacinto Mountains or damming up the wash to play in the water.

Abner’s father, a plasterer, built much of their home. His grandmother ran a rooming house, his uncle a wrecking yard. People hustled to get by. A Mr. Wilson sold homemade gingerbread loaves out of the back of his station wagon.

“People were making a living on Section 14,” Abner said.

Miss Frances’ home was the place to be for animal lovers: She had goats, spider monkeys and an orangutan named Clyde. If you left your keys in the car — people did in those days — Minnie the monkey would shinny up a branch and hide them.

“Minnie was holding a baby one time and the baby’s mother came in and she started to scream,” Abner remembered. The monkey was bottle-feeding the baby. “My grandmother told her to shut up: ‘The monkey was doing what you should have been doing.’”

As far back as the 1940s, Palm Springs had been drawing up plans to develop Section 14.

When the lease limits were extended, Congress declared that Agua Caliente landowners were incompetent to handle their own business affairs. So, working with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Superior Court in Indio dipped into the good ol’ boy network to name conservators and guardians, ostensibly to prevent tribal members from being fleeced. The appointees included the chief of police, real estate agents, a moonlighting judge and Mayor Frank Bogert.

Some conservators were accused of double-billing tribal members, charging exorbitant fees of 25% and selling off land without their knowledge to cover their bills.

Dieter Crawford, a descendant of Section 14 residents on both sides of his family, said conservators “colluded” with the city, sending people to knock on doors when they knew everyone was at school or work. If no one answered, they called in the bulldozers and Fire Department.

Those who didn’t flee Section 14 went through more than a decade of watching their neighborhood being torn apart bit by bit, Michael Hammond, former executive director of the Agua Caliente Cultural Museum, told the Desert Sun.

“We have oral histories ... people got up, went to work, and when they came home, there was no home,” Hammond said in a video for the museum’s 2014 exhibition on Section 14, which later traveled to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian.

The show included a 1961 entry from a Fire Department anniversary book, reflective of the city’s dismissive mentality at the time:

“Several old buildings on Section 14 seemed to suffer from ‘spontaneous’ ignition at different times throughout the year. … These were no-loss fires, the only losses being in the form of firemen’s sleep and part of the city’s water supply.”

Mayor Bogert would later tell the media he had worried that Section 14 could tarnish the city’s allure.

“I was scared to death that someone from Life magazine was going to come out,” he said, according to a Times story in 2001, “and see the poverty, cardboard houses, and do a story about the poor people and horrible conditions in Palm Springs just half a mile from the Desert Inn, our high-class property.”

After congressional hearings, then-U.S. Interior Secretary Stewart Udall declared the conservatorship program “intolerably costly to the Indians in both human and economic terms,” and in 1969 the program was dismantled.

After that, the burnouts bubbled under Palm Springs’ glossy image for the next 50 years. Then they burst out in the racial reckoning following George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police in 2020.

Late last year, a group of former Section 14 residents and their descendants, including those interviewed in this story, filed a reparations claim seeking upwards of $2 billion from the city.

Former residents and their descendants say the city of Palm Springs owes them up to $2 billion in damages for the forcible removal in the 1950s and ‘60s of cooks, chauffeurs and builders who helped turn the desert town into a playground for the stars.

Among other things, the money could go toward cash payments, college funds, infrastructure improvements, a Section 14 memorial park and even a Section 14 Day, attorney Areva Martin said at a community meeting Sunday; the last suggestion was widely applauded. Martin distributed a survey to gauge what form survivors want reparations to take.

The claimants, Palm Springs Section 14 Survivors, say the burnouts drove as many as 2,000 families out of the city, robbing them of political power and generational wealth.

The City Council has apologized for its role in the banishment and is seeking a reparations consultant. Martin, the plaintiffs’ attorney, plans to negotiate a settlement.

The city’s human rights commission called a bronze statue of Bogert on horseback in front of City Hall a painful reminder of the Section 14 removals, and in July the City Council had it removed.

Black and Latino families met at United Methodist Church in Palm Springs on Sunday to discuss upwards of $2 billion in reparations claims against the city of Palm Springs.

The move angered the late mayor’s supporters. Norm King, former Palm Springs city manager, said that the area was a slum and that the Riverside County health department had called for “abatement,” with evictions carried out by the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs, tribal members or their representatives.

“Sadly, the Palm Springs City Council has refused to defend the reputation of the city when it has been falsely accused of improper actions,” said King, adding that Bogert was one of the few who tried to soften the expulsions — fighting hard, if unsuccessfully, for affordable housing when the families were ousted.

Martin said the Reservation living conditions were substandard because the city had refused to provide services, and called efforts to shift blame for the burnouts to tribal members ridiculous.

“They were the only people in the city that would allow Blacks and browns to live on the reservation,” Martin said. “They opened their doors to the residents when the city said, ‘You can’t build over there. You can’t live with the white people’ ... And we are grateful.”

Nowadays the Agua Caliente Band marks Section 14’s transformation as a milestone in tribal sovereignty, the restoration of dominion over ancestral lands. A tribal casino, hotels, a convention center, condos and apartment buildings now sit on Section 14 land, and the Spa at Séc-he opened there this month.

The tribe has steered clear of taking a public stand on reparations, and its chairman and media spokeswoman did not return phone messages seeking comment. Tribal members had lived side by side with Black and Latino residents on their land in Section 14, and also were removed.

Palm Springs today is different from the conservative bastion Bogert once led. It’s now a proud LGBTQ tourist destination with a strong queer community and a reliably Democratic voter base.

But it’s still a small town in some respects, and its history is personal for many.

Bogert’s widow, who is Latina, lives in town, and was appalled by attempts to link him to racism, friends said. Dieter Crawford was friends in high school with Bogert’s granddaughter, a member of Friends of Bogert.

Crawford, 40, is a public health advocate who runs Urban Palm Springs, a digital platform for activism, government affairs advocacy and nonprofit groups that includes its own tour business. Crawford took a Times reporter on a tour of the neighborhoods to which Section 14 families had fled.

He started at Desert Highland, on the city’s north end. The neighborhood had no street lights, no sidewalks and no paved roads when the refugees arrived.

“We’re here to stay”: Black Californians put down roots in the desert

The Gateway Estates tract was built in front of it. Crawford said Gateway was on the sewer system and had gas; Desert Highland was on kerosene and septic tanks. When Black families started buying houses in Gateway, white people left, the fence between them came down and the neighborhoods merged into Desert Highland Gateway Estates, where Crawford grew up.

Today it is the hub of the local Black community — and still lacks investment and infrastructure. Crawford pointed out marijuana grow houses and auto shops that he said foul the air. There are convenience stores, but no supermarket, pharmacy or bank in walking distance.

“I can buy cannabis, tobacco and alcohol to poison myself,” he said. “But I can’t buy a piece of kale.”

Crawford headed to the southern side of Palm Springs and came to the Crossley Tract, named for Lawrence Crossley, a Black trumpet player from New Orleans and a serial entrepreneur who had fingers in pies all over the Coachella Valley. He chauffeured for pioneering Palm Springs developer Prescott T. Stevens, designed the city’s first golf course, and marketed a health tea from a recipe his friends in the Agua Caliente Band gave him.

Crossley relocated Army barracks from a wartime field hospital to his 77-acre site and opened them to Black families, then began to develop single-family housing for his community. The first home was completed in 1958, and the city annexed the area the next year. Crossley, who also managed a water district, became a millionaire.

In 2018, homeowners in the tract protested that a row of 60-foot tamarisk trees on its western border blocked their views of the city-owned golf course and the San Jacinto Mountains, major amenities in Palm Springs real estate. Residents said the billowing “racist trees” were planted to hide Black people.

“The city wasn’t too fond of seeing African American children playing right across from the golf course,” Crawford said.

The city eventually apologized and yanked the trees out.

These days, racism in Palm Springs and its environs is not as stark as a racial covenant, but it’s there, former Section 14 residents say.

Recently, a car wash owner who misunderstood what Taylor’s wife was saying told her not to give Taylor any change.

“He thought I was some Black bum,” Taylor said.

Crawford said that when a white construction supervisor ordered him to leave a public street in Cathedral City, he was angry but not surprised.

“That is what I have to deal with as an African American male in Palm Springs on a daily basis,” he said. “Prejudice at its finest.”

Back in Desert Highland Gateway Estates, pandemic remote workers and California’s housing shortage have pushed property values into the high six figures. Investors are snapping up homes, pricing out younger Black and Latino buyers and changing the neighborhood’s character, Crawford said.

But there is an upside: Some residents are finally reaping some of the generational wealth they lost in the burnouts.

“Imagine how big we could be now,” Crawford said, “if we had been able to purchase homes in downtown Palm Springs.”

As for the former Section 14 residents, reparations might make amends — officially — but they can’t erase the trauma.

Abner still can’t shake dreadful images of the burnouts.

“This dog came running across the street and went up under a house, and the dog was on fire and the house burned up too,” he said.

“I remember like it happened right now.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.