Black and Latino residents burned out of Palm Springs seek city reparations

Pearl Devers was too young to understand why her mother was bundling her and her brothers up and fleeing their family home on tribal land in Palm Springs.

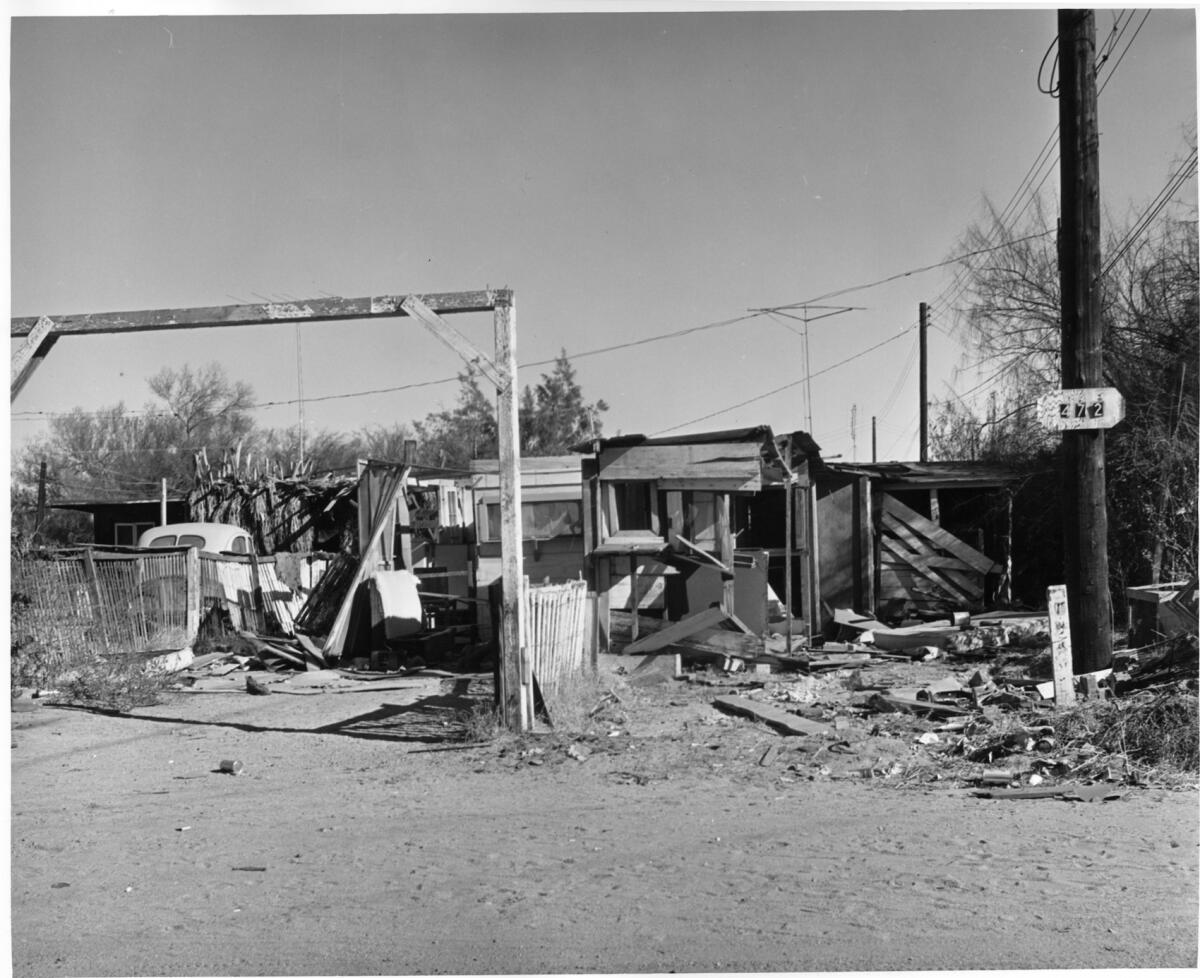

Devers’ father, who built the house with his own hands, stayed behind to make a stand against the brutal 1950s urban renewal project that was seizing their prime downtown land for nothing — no legal process, no compensation, no relocation aid.

In the years after city employees and the Fire Department razed and burned down the houses in the area known as Section 14, Devers said her father, a community spokesperson and devoted family man, fell into alcoholism and never recovered.

“It tore apart my family,” Devers said before a Los Angeles news conference on an amended reparation claim filed Tuesday against the city for what a state official called a “city-engineered holocaust.”

Speakers at the conference in Leimert Park ranked the Section 14 burnout with other historic racial atrocities, including the 1921 Tulsa race massacre in Oklahoma that destroyed a neighborhood called the “Black Wall Street,” and the Rosewood massacre, which wiped out a Black town in Florida in 1923. And they saw their claim as part of the broader reparations movement for Black Americans that recently included compensation for the descendants of the owners of Bruce’s Beach, who were displaced by the city of Manhattan Beach in 1924.

Gov. Gavin Newsom has authorized the return of property known as Bruce’s Beach to the descendants of a Black couple that had been run out of Manhattan Beach almost a century ago. Catch up on The Times’ coverage.

The city of Palm Springs apologized in 2021 for the Section 14 razing and fires, which happened in the 1950s and 1960s. But advocates say there has been no action in 14 months.

In the amended claim filed to the city clerk, former residents and their descendants say the city owes them up to $2 billion in damages for the forcible removals, which took place with little or no notice, and sometimes destroyed houses with personal belongings inside.

The claim identifies 250 survivors and 100 descendants, but advocates expect the final list of claimants to climb. Speakers on Tuesday described the damage estimate of $400 million to $2 billion, developed by their economic consultant, as an opening gambit in what is expected to be complex negotiations with the city.

“Don’t tell me that Palm Springs can’t afford it,” said economist Julianne Malveaux, dean of the Cal State Los Angeles’ College of Ethnic Studies, who developed the $2-billion estimate. “This could be done over a course of five, 10, 20 years. But there must be a possibility of reversing this harm.”

Section 14, 646 acres of downtown property, was owned by the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians and is now the site of a casino, convention center and hotels, although some land remains undeveloped. Known to residents as the reservation, the land was restricted by the federal government to short-term leases until the 1950s.

The tribe leased plots to Black and Latino workers excluded from much of the rest of the city by racist real estate covenants and lending practices. At its peak, activists said, at least 1,000 domestics, chauffeurs, builders and others lived in Section 14, working to turn the desert town into a playground for the wealthy and Hollywood stars like Lucille Ball and Frank Sinatra.

When a prank by Palm Springs High School seniors turned vicious, the principal meted out his own punishment. The outcome satisfied no one in a city with a bitter, divided history.

“They turned this one square mile into a thriving community,” lawyer Areva Martin, who filed the claim on behalf of six Black and Latino claimants, said Tuesday. “A community that had churches and businesses ... where Blacks and Browns lived next door to each other.”

When federal legislators in the mid-to late-1950s eased tribal land restrictions, allowing 99-year leases, the city saw a “huge financial opportunity,” not only to develop luxury properties but to get working-class homes out of sight of tourists and white homeowners, the claim said.

Then-Mayor Frank Bogert, a prime player in the removals, told the Los Angeles Times in 2001, “I was scared to death that someone from Life magazine was going to come out and see the poverty, the cardboard houses, and do a story about the poor people and horrible conditions in Palm Springs,” the claim said.

The city’s razing and burning not only took Black and Latino people’s homes without legal process but robbed them of a chance to build wealth and destabilized their families for generations, speakers said Tuesday.

Devers said her family, unable to obtain a loan or move to many parts of the city, had to jump from place to place, staying at times with friends. Delia Ruiz Taylor, the daughter of Mexican immigrants, said her family moved to a racist neighborhood where kids shouted racial slurs and shot her with a BB gun.

In an 1885 expulsion, the city of Eureka, Calif., put its Chinese residents on two ships and kept them out for seven decades. Now, the Eureka Chinatown Project tells the story.

“We were disrupted and uprooted from our homes; happiness turned to bitterness,” said Ruiz Taylor, who began crying as she recounted her cousin watching her house burn down.

The city of Palm Springs removed a statue of Bogert from in front of City Hall, and is looking for a consultant to help officials set just compensation for Section 14 claimants. However, Mayor Lisa Middleton, in a brief phone interview Tuesday, said the city does not necessarily agree it is liable for all the damages that residents suffered.

“The Palm Springs City Council is committed to trying to fix those damages that we caused. This is a very complex situation and there were many actors involved,” she said. “What we know from history is the city of Palm Springs employees were involved in bulldozing and burning of homes.”

The former head of the Agua Caliente Band has made it clear the tribe “did not believe this was a matter that involved the tribal council,” Middleton said, adding that the city has not and will not try to pull anyone else into the reparations negotiations.

Kate Anderson, director of public relations at the Agua Caliente Band, did not immediately return a phone call for comment.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.