Column: In Mexico stands a lonely monument for a fallen L.A. politician: ‘el licenciado Jose Huizar’

High up in the mountains of the Mexican state of Zacatecas, in the desolate village of Los Morales, a monument stands to former Los Angeles Councilman José Huizar.

Yes, that guy.

The very same who’s currently facing federal criminal charges of racketeering, money laundering and bribery. The same José Huizar once held up in Southern California political circles as a bootstrap success story, but who now serves as a cautionary tale about the perils of power.

At least they still love him in Los Morales, the rancho where he was born.

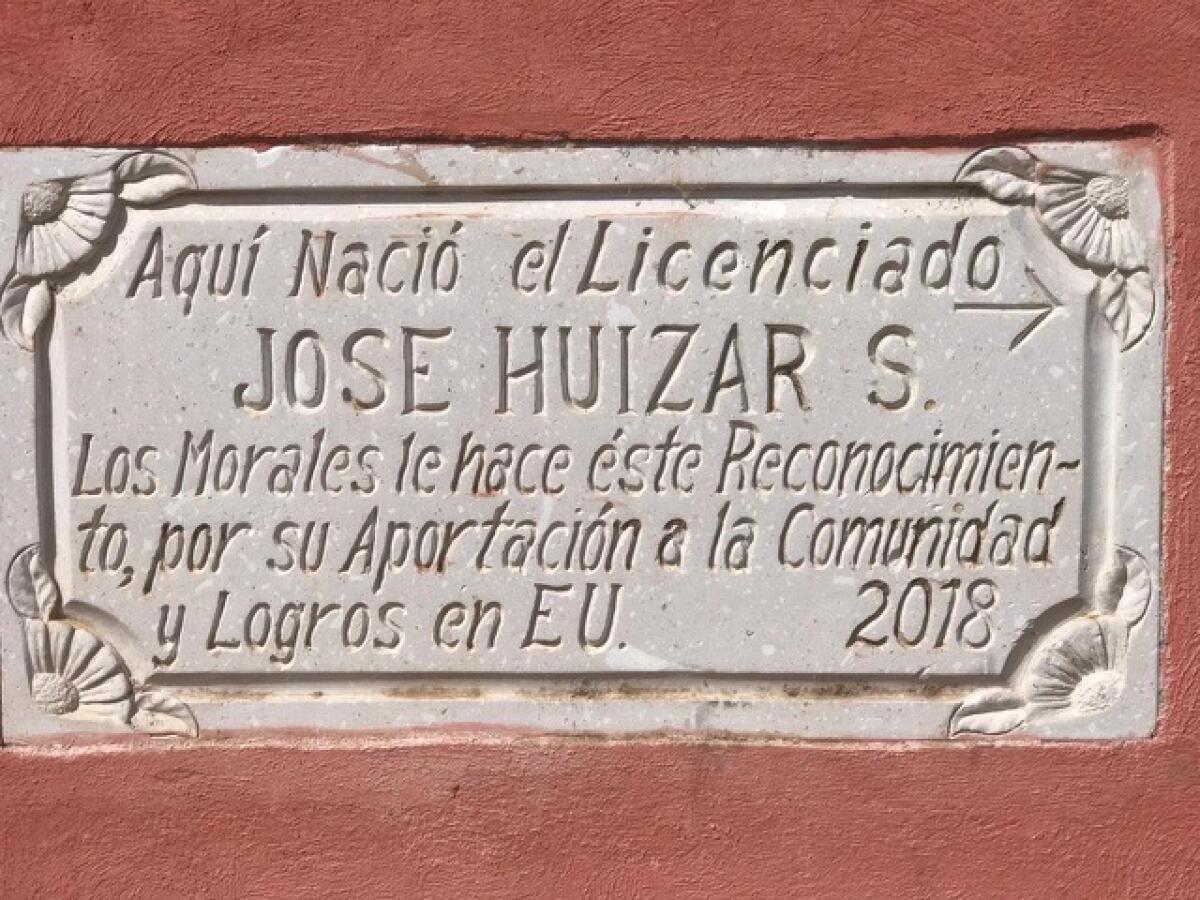

The monument is a simple concrete marker set on a sandstone-colored pillar just outside his family’s home.

“Here was born el licenciado Jose Huizar,” it reads, using the Mexican-Spanish honorific for a lawyer but also a term used for anyone perceived to be a professional.

The inscription further states that Los Morales erected this “recognition” to its native son in 2018 for “his contributions to the community and accomplishments in the United States.”

I know Los Morales well. It’s in between the ancestral villages of my parents (El Cargadero for my mami, Jomulquillo for my papi), which I haven’t visited since college but whose comings and goings are part of my daily life. They’re all part of the galaxy of ranchos around the city of Jerez that has sent tens of thousands of its residents to Southern California over the last 120 years.

The chisme from the ranchos is like a real-life Lake Wobegon — who married whom, which village made the best cheese this year, what cousin wants to move up to the United States permanently to escape the cartel violence that has sadly gripped the region. The jerezano circle is close enough that I’m still Facebook and Instagram friends with Huizar, although he hasn’t commented on my stuff ever since the FBI arrested him in the summer of 2020.

Southern California’s boy king of saints, the Santo Niño de Atocha, gets dragged into political scandal

That’s why I was surprised that I didn’t hear about Huizar’s monument until a couple of weeks ago, when my dad randomly told me about it. He and my mother knew Huizar’s parents well enough that my dad refers to Huizar’s late father as Don Simón, and José’s mother as Chila, the Mexican-Spanish nickname for any Mexican woman named Isidra. My dad said he even saw Huizar’s brother a couple of weeks ago at a rodeo in Perris.

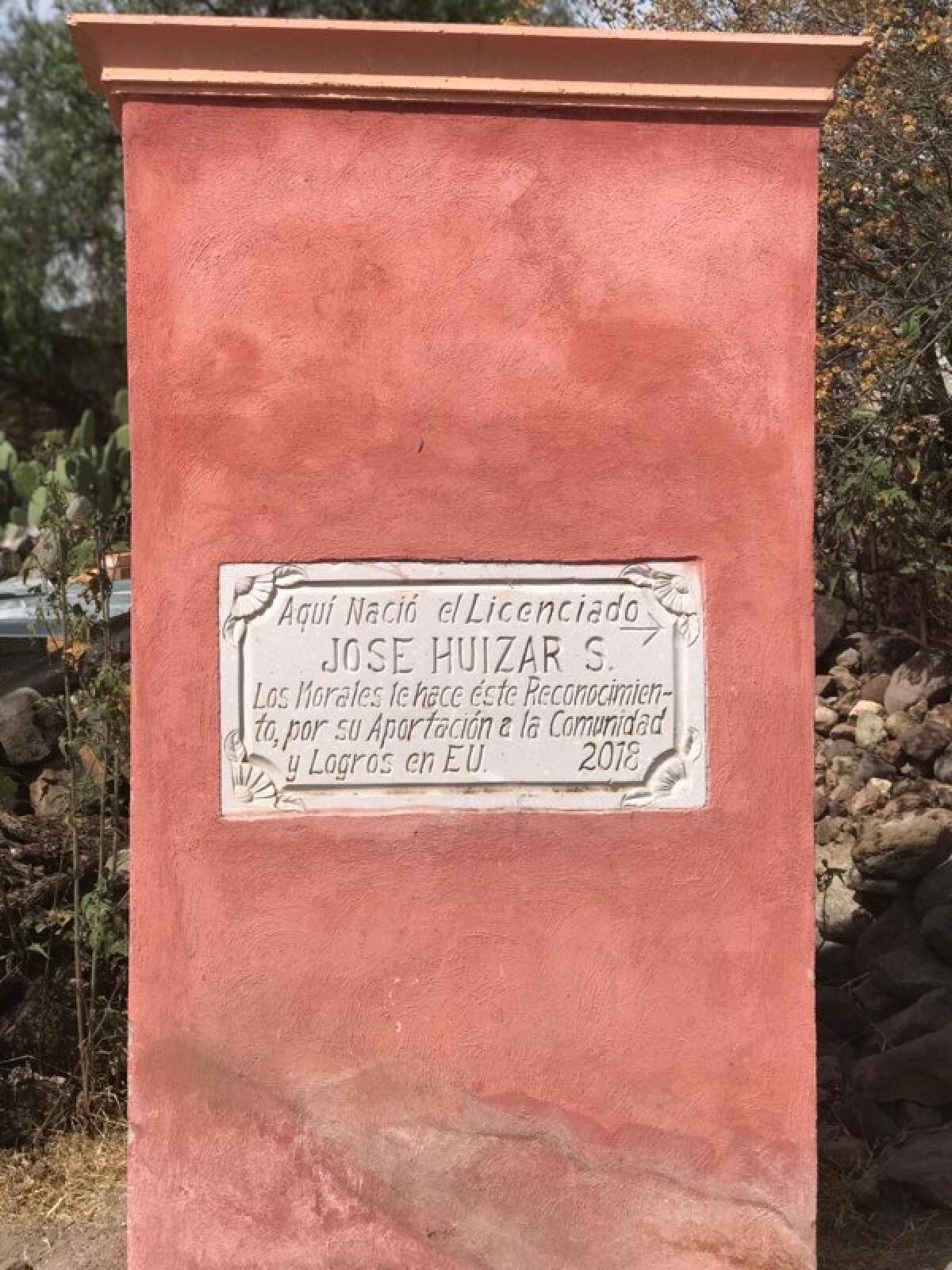

Papi first said that Huizar’s monument was a statue, then said it was a pillar, then said a plaque (rancho gossip, I’m telling you). So I had a friend who still lives in Jerez visit Los Morales to take a photo, which I showed to my dad.

He and his compadres long maintained that Huizar was innocent of all charges, with no proof whatsoever. But when I showed him the picture of Huizar’s plaque, Papi was more philosophical. “He deserves it, because he did do good at first,” he responded. “I just hope he’s praying to God to forgive his sins.”

We erect monuments to celebrate heroes or victories, not commemorate villains and defeats. That’s why so many of them have come down in the last couple of years, as Americans have reassessed who from the past continues to deserve lionization, and who deserves a literal trip to the scrap heap.

Huizar, despite his sins, deserves the former. So I hope the people in Los Morales leave his marker no matter what happens to their hometown hero. And I hope that the multiple markers across Los Angeles that bear Huizar’s name — even though they have nothing to do with him, really — are also left alone.

His name is on a bronze plaque at El Sereno Middle School to honor the 50th anniversary of the Chicano Blowouts. On the base of the bracero statue in downtown Los Angeles, and the one of ranchera icon and fellow zacatecano Antonio Aguilar off Olvera Street. “Jose Huizar” is on a marker in a median on Eagle Park Boulevard commissioned by the Glassell Park Improvement Assn. to thank Huizar and other council members “for their ongoing support.”

And the ex-council member’s name is also on a monument in front of Farmdale Elementary School in El Sereno that honors a longtime volunteer, with Huizar’s name as big as that of the honoree.

We should all remember who Huizar was, and who he became. Seeing his name should inspire a Pavlovian reaction to straighten up and act right. No one feels this more than Huizar’s fellow SoCal jerezanos. We had so much hope for him — one time, I even invited him to be a judge at a taco tournament — and now must bear the stain of his name.

UC Riverside ethnic studies professor Adrián Félix saw Huizar multiple times at the annual banquets of the Federación de Clubes Zacatecanos del Sur de California, whose members organize fundraisers for their home ranchos.

“He was a celebrity to everyone there,” said the professor. “He was working his crowd, but there was a pride to everyone because he was one of them.”

Félix admitted to being “really disappointed” when news of Huizar’s arrest broke. “Now, in some ways, I see it as kind of predictable. But his ascendancy to power was important, and hopefully we have more people like that who don’t fall down to that same turn.”

One of those people is Maywood Mayor Heber Marquez, who was born in Jerez. He actually never heard of Huizar until the high school teacher ran for City Council in 2018. The shady zacatecano politician for him was former Maywood Mayor Ramon Medina, who’s also charged with multiple felonies for alleged civic corruption.

“When I ran, and people found out where I was from, they’d say, ‘Oh, you’re from Zacatecas — how’s that going to turn out?’” said the 36-year-old with a bitter laugh. “That’s when I thought, ‘Do I see myself continuing in this path? Should I stop now?’”

Marquez was appointed Maywood’s mayor this year, and he hopes to use his position to bring pride back to zacatecanos in the Southland.

“Jerez is much more than Huizar,” he said. “Our people represent much more, and deserve much more. We shouldn’t see ourselves in him.”

Which takes me back to Huizar’s monument in Los Morales. The photo that my friend took shows that a crack formed at the bottom of the pillar that someone tried to patch up. We cannot erase what Huizar did, nor should we.

But we can look on as his legacy continues to crumble, and accept the lessons.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.