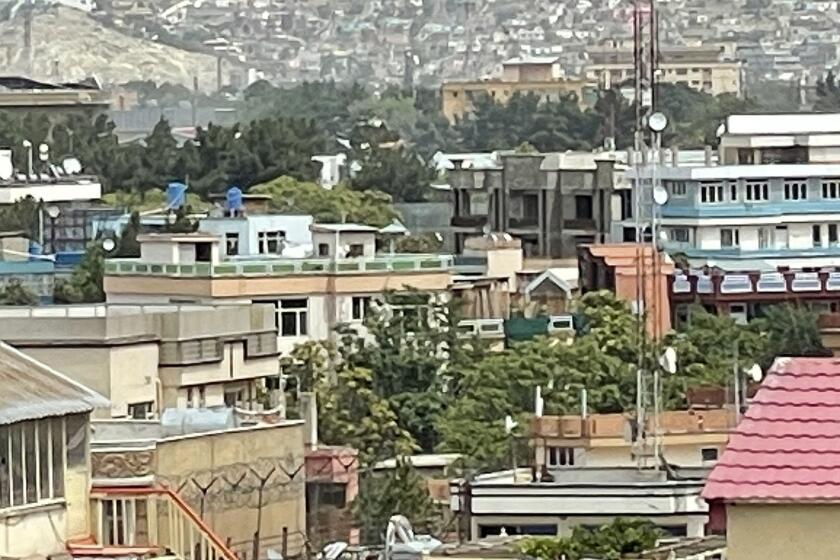

‘I want to leave more than ever’: A year after U.S. pullout, Kabul is a city in despair

KABUL — Standing on the side of a mud-crusted street by a sewage canal, Shafiullah heaved a 110-pound bag of flour into the trunk of his battered Toyota Corolla and sighed. Beside him, a shambolic queue of residents of this once-affluent neighborhood, all waiting for their monthly U.N.-supplied assistance package, stretched to the end of the block and around two corners, then wrapped around the corner twice more, a physical representation of the five-hour wait Shafiullah had just finished.

“This is like begging. Sometimes you wait all day for this bag of flour,” the former member of Afghanistan’s vanquished U.S.-backed army said bitterly. The aid package will last him, his wife, his sister and his mother for a month, he said; after that, he doesn’t know what he’ll do.

“Before, I made enough money I could help other poor people,” said Shafiullah, 27, who gave only his first name for privacy reasons. “Now I’m the one who needs help.”

On the other side of Kabul, past dilapidated houses and drug addicts clustered in a graveyard, worshipers held their collective breath as they met for Friday prayers on the upper floor of the Abu Bakr Al-Siddique Mosque. Praying downstairs was impossible: Days earlier, an Islamic State bomb ripped through the ground floor with enough strength to blow out the door and shatter the windows of nearby houses, killing 21 people.

Now, the congregants pray under the watchful eyes of eight Kalashnikov-toting Taliban fighters, with a Humvee and machine-gun-equipped truck nearby for extra security.

A year after the Taliban’s stunningly swift takeover and the U.S.-backed government’s disintegration, Kabul, the Afghan capital, is a city bereft. Of economic spark, as jobs vanish, shops and restaurants shut and an ever-increasing number of beggars camp outside bakeries hoping for a morsel of bread. Of safety, as destitution fuels a crime wave even as terrorist attacks — though reduced — continue to kill and maim. Of opportunity, especially for women and girls. Of hope.

About 94,000 Afghanistan evacuees have arrived as part of the U.S. effort to resettle vulnerable refugees, including those who worked for the U.S.

The slashing of foreign aid, along with U.S. sanctions and the seizure of the Afghan central bank’s assets, has shrunk the nation’s economy by a third, plunging all but 3% of Afghanistan’s 40 million people below the poverty line, aid groups say. Despite relief that the 20-year war between the Taliban and occupying Western forces has ended — especially in the countryside, where the fight was at its most intense — the unanimous complaint among Kabul residents, even those inclined to think well of the Taliban, is that there is no money and no prospects for meaningful employment.

They refer to the Afghan republic’s destruction as the “suqoot,” the fall, less with rage at the betrayal by their former leaders — though there is that — than with the resignation of a people who believe they’ve missed their chance. They express frustration that their new rulers in the now-renamed Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan refuse to take any steps to unblock the international restrictions that have paralyzed the financial system and all but eviscerated the economy.

There’s a palpable sense among many Kabulis of giving up on their country. Conversations inevitably turn to ways to get out.

“I can’t go to university for the work I want to do. I can’t find a job,” said Anita Husseini, 21, a student who speaks crisp English from years of study to be a teacher. “I didn’t want to stay before, but now I want to leave more than ever.”

Walking with her teenage sister by a bridge over the nearby Paghman River on her way home, Husseini dismissed the Taliban as a “disaster” who left no room for anyone — men or women — to do anything. “She can’t go to school,” Husseini said, gesturing at her sister, who stood silently by her side.

Even the Taliban’s often-repeated assertion that its return to power would herald an era of peace and security hasn’t been fulfilled, at least not in Kabul, she said, with Islamic State suicide bombers, rocket salvos and assassinations a regular threat.

Particularly vulnerable — and uneasy — are ethnic minority Hazaras like Husseini. Most are Shiite Muslims, making them a prime target for attacks by Sunni-dominated Islamic State. Three such attacks took place earlier this month, adding to the at least 68 recorded incidents of explosive weapons being used in Afghanistan so far this year, which have killed more than 300 people and injured twice that many, according to the British-based nonprofit organization Action on Armed Violence.

A year after Taliban fighters entered Kabul, here are the stories of four Afghan refugees and the objects they took with them.

“Even safety isn’t there. Yes, there are less intihaari bombings because the Taliban themselves were the intihaaris and they’re now in charge,” Husseini said, using the Dari word for “suicide bomber.”

Suicide attacks were a frequent tactic employed by the Taliban during its insurgency against Afghanistan’s U.S.-backed government. Taliban officials insist that safety has improved overall but concede that stopping suicide bombers is difficult.

Of greater concern to Husseini are the burglaries that she said are now a commonplace occurrence in the Kart-e-Say neighborhood where she and her family live. She noted that, before the suqoot, people used to walk around the neighborhood till 9 p.m. with little fear, despite the wartime threats; now, even the banana cart owner who has sold his produce for 20 years from this corner of the bridge leaves by 7 p.m.

“The danger is from normal people because of lack of work, lack of money,” Husseini said.

President Biden will sign an executive order calling for frozen Afghan funds to be split between 9/11 victims and humanitarian relief in Afghanistan.

As she spoke, she glanced at the river’s edge, where a pair of emaciated, dirt-streaked men stared into the distance.

“Drug addicts,” a passerby explained as Husseini and her sister looked away. “Opium.”

One of the men, who gave his name as Turjan, stood up and resumed collecting pieces of plastic that he stuffed into a large bag. Later, he would be able to sell the refuse for 50 afghanis — a little more than 55 cents.

“This is all I can manage,” he said, his voice as slight as his frame. His friend, a sharp-featured man in his 20s named Ali Reza, joined the conversation, railing against the Taliban’s treatment of him and his friends.

“They don’t care about us. They treat us like garbage,” Reza said, his movements turning manic as his anger mounted. Although his family is in Iran, he showed no interest in joining them nor in submitting to treatment for his addiction. “This is my place. If I go to the hospital, it’s the worst place ever,” he said. “I prefer to live under the bridge rather than go back there.”

On the surface at least, some things in Kabul remain unchanged.

The Green Zone, the fortified enclave that was once home to foreign diplomats and the Afghans who grew rich from the Western invasion, remains in place, but now with high-ranking Taliban officials — and Al Qaeda leader Ayman Zawahiri, who was killed in a U.S. drone strike in the posh Sherpur district last month — occupying the garish mansions instead of local warlords. Checkpoints still snarl traffic.

Taliban patrols roam the streets in Ford Ranger pickups commandeered from the previous government. Some haven’t even bothered to remove the old Afghan army’s tricolor insignia.

Experts say Ayman Zawahiri’s death won’t affect Al Qaeda’s operations, but it raises questions about the group’s links to the Taliban.

Yet no matter how effective the security may be, it’s virtually meaningless for 35-year-old Ahmadullah Safi. Like Shafiullah, Safi had been waiting near the United Nations aid distribution site since just after dawn prayers.

Unlike Shafiullah, Safi stood in a parallel queue of porters with wheelbarrows helping ferry recipients’ aid packages to vehicles or homes for 30 afghani, about 34 cents. On his best days, he clears little more than $3; usually it’s half that. In any case, it barely covers the needs of his wife and three children, ages 7, 6 and 3.

“I’m hungry. What do you want me to do with security? How can I eat it?” he said.

His rent has increased by 500 afghani — almost $6 — in the last few months.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“How can I afford anything? All prices are up,” he said. “I’ve been helping people move bags of flour and I don’t even have a kilo of flour at home.”

Despite the desperation, deprivation and decreasing opportunities, some Kabulis have tried to preserve some vestige of their pre-Islamic Emirate existence and forge some kind of modus vivendi with the Taliban.

A few blocks up from the bridge over the Paghman River, 28-year-old Froozan Hotami descended the stairs of a shopping center to join a smattering of women already gathered for what seems almost like an illicit activity these days: the opening of a women-only library, called “Zan,” the word for “woman” in Dari. Nearby was a cosmetics shop and a couple of bodybuilding supply stores featuring photos of men with impossibly large biceps and jars of whey protein powder.

The library opening, attended by around two dozen women, had the frisson one would expect to feel at a speakeasy, with people milling around shelves lined with copies of Michelle Obama’s “Becoming” and a wall of posters of important female figures from Afghanistan’s past, including Kubra Noorzai, the country’s first female government minister.

As a co-founder of the library, Hotami, who had worked in one of the republic’s ministries — she demurred from saying which — sees Zan as a way to fight being treated as a second-class citizen by the Taliban, especially after being all but forgotten by the international community, she said.

She cited the Taliban repeatedly delaying the reopening of secondary schools for girls, on the vague grounds of needing to provide a safe learning environment without actually defining what that is, and their barring of women from most professions. The moves flout the Taliban’s promises that it would allow girls to resume secondary schooling in March and that men and women would have equal rights.

“We all know women’s situation here. It’s disappointing, heartbreaking,” Hotami said. “Despite all the Taliban’s efforts, women continue working, continue doing. We all must be responsible. The international community must be responsible.”

The burqa order confirms the worst fears of rights activists and is sure to complicate the Taliban’s dealings with the international community.

Also soldiering on are Kabul’s wedding halls, though in diminished form. Before the Taliban came to the capital, weddings were big business, with gargantuan, gaudy halls like the one in the upscale Shahr-e-Naw neighborhood hosting parties 1,000 people strong, featuring musicians, dancers and magicians.

Much of that is all but outlawed now, said Hamid Qazikhil, one of the wedding hall’s managers, and a number of compromises are required to adhere to the Taliban’s more austere interpretation of moral behavior, including the complete segregation of men and women.

“No dancers or magicians, of course. We can’t use musicians so we have DJs now, though only in the women’s section,” Qazikhil said.

Qazikhil walked toward one of the ballrooms in the hall, showing the polished white partitions stacked on the side that would be set up to separate men and women. That particular ballroom, he said, had been renovated just five days before the Taliban entered the capital Aug. 15, 2021. It had been a massive waste, he said with a wan smile, adding that, with the general lack of money, few weddings exceed 200 or 300 people now and business has shrunk from 60 weddings a month, with the hall booked day and night, to almost half that number.

Charity foundations, street names and a mural are among the tributes to the fallen, most of whom were based at Camp Pendleton.

“These weddings now, there’s not too much enjoyment. Just coming, eating and then leaving,” he said. “It’s all sort of less fun, really.”

Daud Sultanzoy was Kabul’s last mayor under the republic and is one of the few officials who stayed on after the Taliban takeover to help with the transition. He left the country a few months ago but hopes to return.

Though he was initially hopeful that the war’s end would bring benefits, a year of Taliban control has yielded few of them. And even if the new regime could offer physical security, it would not know how to capitalize on it, he said.

“Security is more than the absence of bombs and bullets. It’s not an end. It’s a means to use as a springboard to do other things, it’s a condition, and if it’s there, then it should produce something,” he said. But all that the Taliban’s leaders have produced so far is a monopolistic grip on power, because that is the one thing they know how to do, he said.

“Now that they have produced this, then the burden is on them, and the international community that put Afghanistan in this situation, to look at the 40 million people, their aspirations and needs — just basic needs of human beings in the 21st century, to not become a burden on the rest of the world.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.