KABUL — The capital’s morning rush hour is a discordant backdrop for the workshop of Izzatullah Neamat. But walk down an alley, sidestep a sewage canal, and there he is: ensconced in the rabble among dozens of rubabs — an ancient instrument that resembles a lute — that have become his life’s work and family legacy.

Here on the outskirts of Kharabat, the city’s oldest quarter and the onetime home of its musicians and artists, the 40-year-old Neamat is a keeper of an Afghan tradition that was all but stamped out in the chaos of war and the harsh rule of religious extremists who — hearing sin instead of song — outlawed music and threatened with death its practitioners.

And it’s set to happen again. U.S. and NATO forces plan to depart the country in as little as a few weeks, leaving behind an Afghan state that few believe can withstand a Taliban onslaught. In recent days, the group has overrun dozens of districts, while its spokesmen discuss controlling and imposing its harsh religious vision on the country with an air of inevitability.

Among the many losers of such a takeover are instrument makers like Neamat, as well as the musicians he serves. For them, there appears to be one solution:

“Faraar,” said Neamat. Escape.

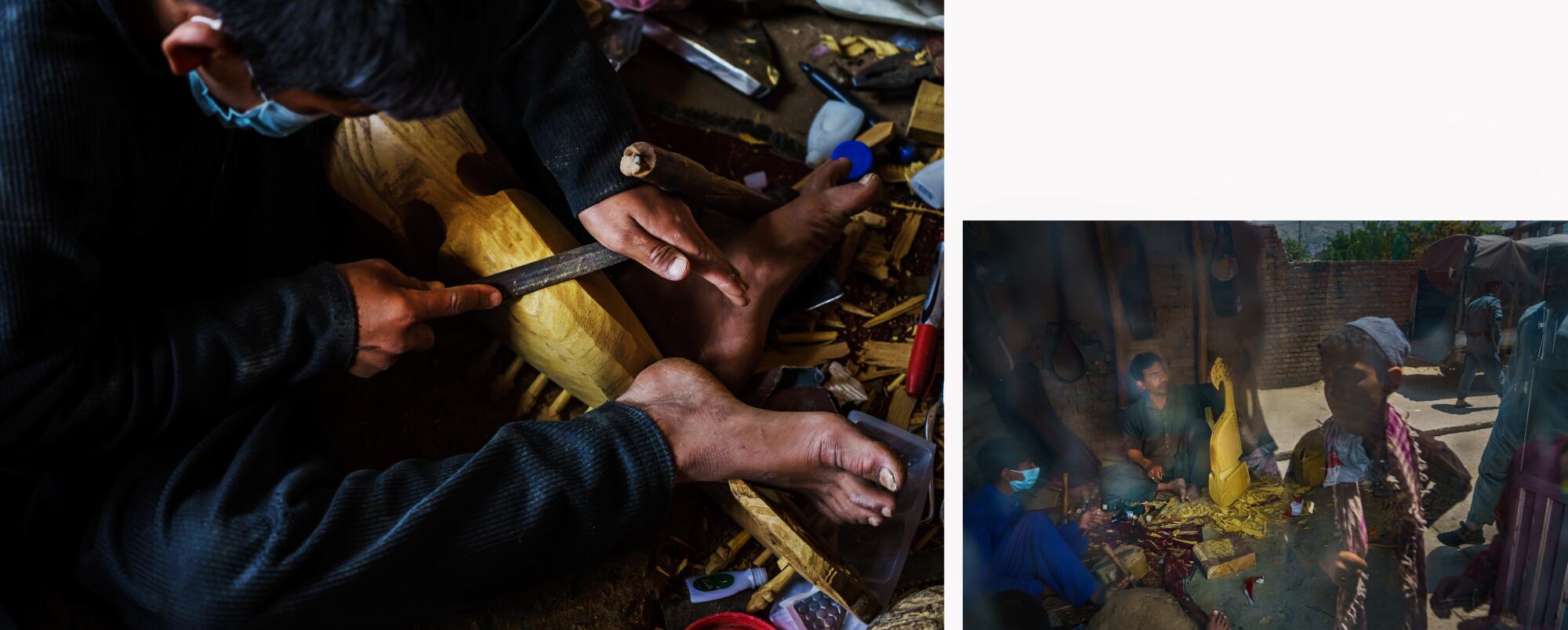

He sat on the floor, wedged the end of a half-finished rubab into the ball of his foot and set to work with a knife on the intricate filigree near the scroll. Watching him was Ramin Saqizada, a famed 32-year-old rubab virtuoso and teacher in Kabul. Like other rubab players, Saqizada often comes to hang out in Neamat’s tiny one-room workshop, where their voices mingle with outside traffic and the rat-tat-tat of men who cut and hammer metal for a living. The discussion — as it has of late —veered to what would happen when the Taliban comes.

“All of the musicians in Afghanistan will stop. We’re just praying to God for us to have peace,” Saqizada said. “If the Taliban leave us alone it would be fine. But they won’t.”

Beside him was rubab player Mohammad Kabir, 38, who nodded and said he had already bid farewell to a friend three weeks ago who escaped to Iran.

“The Afghan government can’t protect us,” he said.

In many ways, their story was a refrain of an earlier generation’s woes, before the U.S. invaded and upended the Taliban in 2001.

Saqizada’s father Mohammad, also a rubab player, had fled Kabul with the family to Pakistan’s Peshawar in 1992, when the mujahedin, Islamist Afghan guerrilla factions, toppled the Soviet-backed communist government. Musicians and artists became easy targets for those looking to burnish their religious zeal. In the civil war that followed, Kharabat was destroyed, female singers were banned and music was restricted. When Taliban fighters entered Kabul in 1996, they brought a measure of stability but also their fundamentalist rule, which outlawed all music as well as radios and TVs.

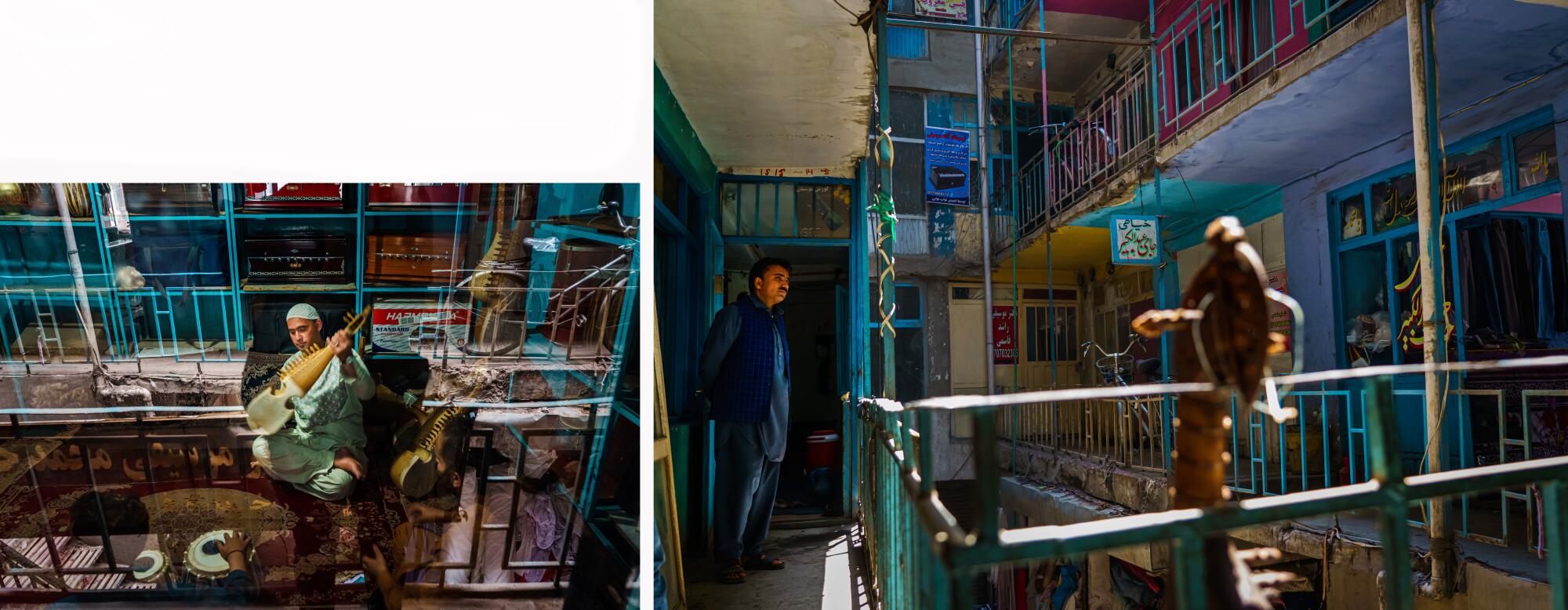

After the Sept. 11 attacks and the U.S. invasion removed the Taliban from power, Saqizada’s family returned as part of a fragile artist community working to restore Afghanistan’s classic music. It’s an art where the rubab plays a defining role — Afghans call it “the lion of instruments.” Its picking and strumming can mirror the ebbs and flows of ghazal song poems, or if it’s heard solo, its strings resonate across the spectrum of a virtuoso’s improvisations.

Over the years, Saqizada had taken his artistry to packed audiences in Germany and Denmark. Though he could have stayed abroad, the 32-year-old insisted on playing and teaching in Kabul “because my father’s name should stay alive.” With colleagues, he formed the “Safar” project, which aims to preserve Afghanistan’s music, and worked in the country’s national music institute.

A dark-haired man with serious eyes, he spoke in rapid-fire Dari. He held an ornate light-colored rubab, his fingers flitting across the fingerboard, his face moving as a ventriloquist would, as if he were channeling his voice through the instrument. To leave Afghanistan would mean a life away from his family, but to stay under the Taliban’s harsh edicts meant nothing less than the loss of his identity.

“With the rubab, I’m Ustad Ramin,” he said, referring to himself with the honorific given to master musicians.

“Without it, I’m not an Ustad. I don’t know what I will become.”

Neamat, though, had already made peace with the idea that he would leave.

“I’m not about mullah or Talib. Just music. If something is coming to all people, I have to accept it,” he said, adding that he planned to go to Pakistan, where his family had weathered the Afghan-Soviet war and the conflicts that followed before returning to Kabul in 2004.

“Many of my friends are already there,” he said, “and they’re telling me I could open a workshop.”

Like his father and grandfather before him, Neamat first learned the craft of making a rubab as a child, whittling down small pieces of wood to make the intricately shaped tuning pegs. That job was now relegated to his son, 11-year-old Hidayat, and his 17-year-old nephew, Jawad Waseli; both were sitting cross-legged near Neamat, a pile of curled wood shavings growing between them.

Neamat brandished an adz and hacked the sharp corners of a piece of a mulberry tree trunk into the rounded outline of the rubab it would become in 10 days. It was rough work, but once satisfied, he switched to a chisel and hammer to hollow out the rubab’s badanah, or sound box, to a thickness of less than an inch. Toward the end, he’ll cover it with animal skin, place tiny bone supports on its side and install three main playing strings, two drone strings and more than a dozen sympathetic strings.

If the customer asked, he would decorate the neck or the body with intricate mother-of-pearl inlays; for others, the brown of the unvarnished mulberry wood — its espresso-crema shade grows a deeper brown with the years — was decoration enough.

The finest of his instruments, Neamat said, were abroad in Pakistan, Germany or the U.S. with artists such as Homayoun Sakhi, a rubab master who since 2002 has lived in Fremont, Calif. (The area is known as “Little Kabul.”)

At home, you could hear Neamat’s rubabs in the hands of traditional wedding performers all over Afghanistan, especially among those in nearby Shor Bazaar, a ramshackle neighborhood whose cheap rents had made it an alternative home to artists after Kharabat’s destruction.

But you heard them less these days. With Taliban fighters advancing to the edge of Afghanistan’s major cities and controlling the nation’s highways, musicians were reluctant to perform in weddings outside of Kabul. Pandemic lockdowns also kept them from traveling, but even when restrictions were lifted, some had already glimpsed what awaited them in a Taliban takeover.

“The other day we left a wedding party and the Taliban shot 16 bullets at our car,” said Nawab Nawabi, a harmonia player in the Ghos al Din building in Shor Bazaar.

“We went to the police and they said ‘Don’t worry about it because no one can catch the Taliban. They’ll kill you and us.”

It was little better inside the capital, said Sheer Agha Mumen Khan, a rubab teacher. In years past, he would perform at parties every night. But as security worsened, so did his work schedule, which dwindled to roughly two events a month. Finally he was forced to give up performing altogether and dedicate himself to teaching from his two-room music school in the Ghos al Din building.

“There’s no security. After a wedding, we come back at midnight and it’s just too unsafe with thieves,” he said.

A slight 41-year-old man, he glanced at the row of rubabs hanging on his wall, his eyes setting on a particularly aged instrument that he said belonged to his grandfather, who had first inspired him to become a musician. He didn’t understand why the Taliban would consider such a thing haram, or forbidden.

“They say it’s like drinking alcohol. But you make people happy with music. What’s the problem? It’s just music,” he said, recounting how he had seen Taliban recoil at the first sound of notes playing as he picked up his grandfather’s instrument and gave a few cautious strums to test its tuning.

“The musician works with his hands. If someone takes this from him what can he do?” he said, looking down at the rubab. “What can I do?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.