Al Qaeda leader’s death raises concerns over Taliban links, Afghanistan’s future

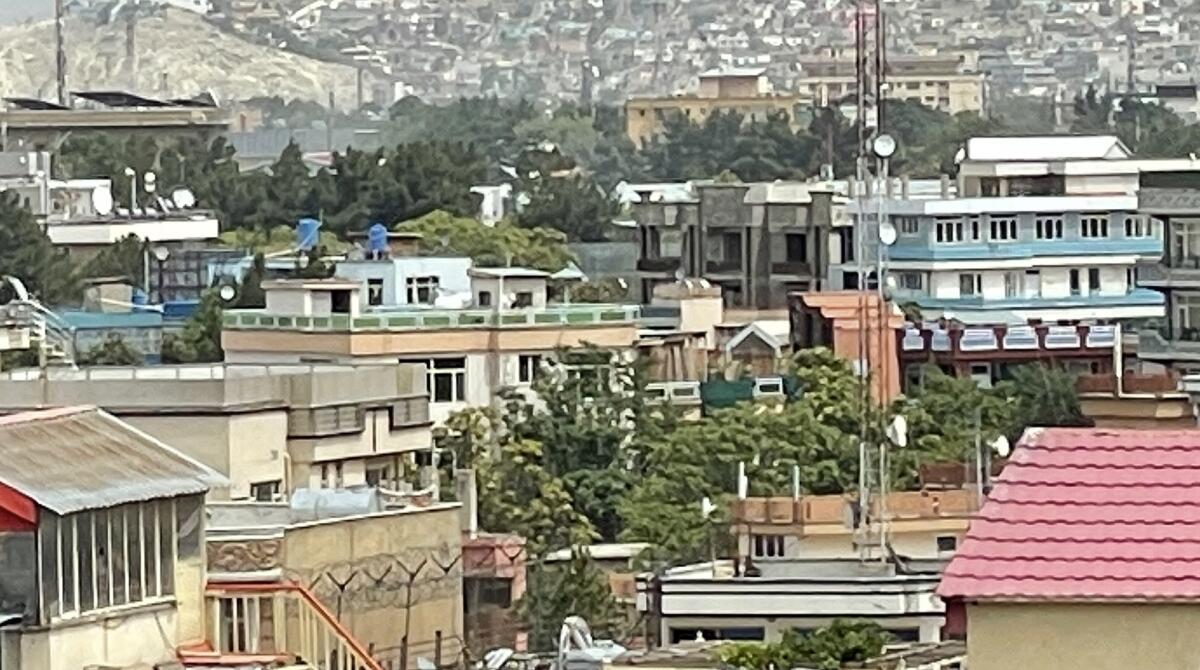

BEIRUT — By the time two U.S. Hellfire missiles slammed into the balcony of a house in downtown Kabul early Sunday morning and killed Ayman Zawahiri, the 71-year-old Al Qaeda leader had become increasingly irrelevant to the organization he had once helped shape into one of the world’s most dangerous jihadi groups.

For his role as a chief architect of the attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, Washington had placed a $25-million bounty on his head. It persisted in a frustratingly long manhunt that, after 21 years of false leads and near-misses, zeroed in on a house in the Shirpur district, one of the Afghan capital’s more upscale neighborhoods about a mile from the former American Embassy compound.

President Biden said Zawahiri’s killing delivered justice to “a vicious and determined killer.” Analysts, however, say his death constitutes little more than a symbolic blow to an Al Qaeda that has changed much since he helped orchestrate the strike that killed 2,977 people — the deadliest foreign attack on American soil. The greatest impact from Zawahiri’s demise may resonate in Afghanistan, which he drew into a destructive war with the U.S., and which now could suffer anew amid Western concerns over Al Qaeda’s entrenchment in the country and its close ties with the ruling Taliban.

“We shouldn’t underplay the element of justice, but Zawahiri [at his time of death] was not the heavy hitter he once was,” said Tallha Abdulrazaq, a researcher at the University of Exeter’s Strategy and Security Institute. “He was a figurehead, but his reach was very limited.”

Much of that was due to a relentless two-decades-long campaign by the U.S. to disrupt Al Qaeda and hunt down the terrorist network’s leaders. It succeeded in getting Osama bin Laden, Zawahiri’s friend and predecessor at Al Qaeda’s helm, who was killed in May 2011 when a Navy SEAL team stormed his compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan.

But it also forced a decentralization that saw Al Qaeda’s main leadership cede control to more active affiliates, such as its Yemeni branch, Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula; Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, which operates in the Sahel region; and Somalia’s Shabab.

Though those groups’ so-called emirs, or commanders, pledged fealty to Zawahiri, it was unclear how much tactical or strategic input he had on their operations. And his influence as a jihadi inspiration waned further when he failed to rein in the leaders of other one-time affiliates, including Abu Bakr Baghdadi, whose group, Islamic State, waged a brutal campaign that saw it establish a so-called caliphate over a third of Syria and Iraq, and, for a time, eclipse Al Qaeda.

In contrast to Bin Laden, a charismatic speaker whose video appearances would galvanize the group’s followers worldwide, Zawahiri instead often came off as a ponderously boring uncle, engaging in hours-long sermons that did little to endear him to a new generation of jihadis raised in an era of branding and social media.

“A lot of people thought he was already dead. Strategically and operationally for Al Qaeda he was no longer that important,” said Ashley Jackson, co-director of the Center for the Study of Armed Groups. She added that Al Qaeda had become more focused on victories in its affiliates’ local conflicts rather than attacking the United States.

The killing of one of America’s top adversaries provides a much-needed boost for Biden ahead of the midterm elections, but it has also renewed concerns over his administration’s decision to withdraw from Afghanistan last year, in effect allowing the Taliban to seize the country. That Zawahiri was killed in Kabul was another unsettling indication of Washington’s failure to scour Al Qaeda from Afghanistan even after nearly 20 years of occupation.

Since the U.S. withdrawal, according to a report by a monitoring group that was submitted to the United Nations Security Council in July, Al Qaeda has “enjoyed greater freedom in Afghanistan under Taliban rule.” Still, Al Qaeda was not viewed as posing an immediate international threat from a haven in Afghanistan, the report says, because the group lacked “an external operational capability and does not currently wish to cause the Taliban international difficulty or embarrassment.” Meanwhile, Zawahiri’s apparent increased comfort and ability to communicate “coincided with the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan and the consolidation of power of key Al Qaeda allies within their de facto administration.”

Undergirding Biden’s withdrawal decision was the 2020 Doha agreement, which the Taliban leaders signed with the Trump administration and which stipulated the Taliban would not host or cooperate with Al Qaeda and any other group threatening the U.S. or its allies, or allow them to launch attacks from Afghan territory. Biden also insisted at the time that the U.S. would be able to conduct “over-the-horizon” operations (in other words, drone strikes) to deal with any terrorist threat in Afghanistan — a pledge that on Monday he said was fulfilled with the Zawahiri operation.

“When I ended our military mission in Afghanistan almost a year ago, I made the decision that after 20 years of war, the United States no longer needed thousands of boots on the ground in Afghanistan to protect America from terrorists who seek to do us harm,” he said.

“And I made a promise to the American people that we’d continue to conduct effective counterterrorism operations in Afghanistan and beyond. We’ve done just that.”

But a thornier question is the extent of the Taliban’s involvement with Zawahiri and what it means for the group’s efforts to gain international legitimacy and restore billions of dollars in acutely needed Western aid. Afghanistan’s economy has tanked in the wake of the U.S. pullout, with sanctions, frozen reserves, COVID-19 and, now, the war in Ukraine pushing millions to face a winter without enough food, the U.N. says.

That the increasingly isolated Taliban knew of his presence in the Afghan capital does not appear to be in doubt: A senior administration official said that members of the Haqqani network, which enjoys a particularly close relationship with Al Qaeda and is a major part of the Taliban government, had evacuated Zawahiri’s relatives from the Shirpur house shortly after the strike in a bid to hide their presence. The official added that the Taliban’s hosting of Zawahiri amounted to a violation of the Doha agreement.

The Taliban, meanwhile, said it was the U.S. attack that violated the Doha accord.

“Such actions are a repetition of the failed experiences of the past 20 years and are against the interests of the USA, Afghanistan and the region,” said Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid in a curt statement Monday. He did not mention Zawahiri’s name but added that “repeating such actions will damage the existing opportunities.”

The fracas comes at a delicate time: In late July, Taliban and U.S. delegations met in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, to discuss releasing half of about $7 billion in legal Afghan central bank reserves, which the U.S. had seized in the wake of its withdrawal.

The Zawahiri attack could strengthen more radical elements within the Taliban leadership, especially those who disagreed with the accord with the U.S. in the first place, said Hasan Abu Haniyeh, a Jordan-based expert on jihadi groups.

“There are those who will say the U.S. is already not adhering to the agreement, that the conversation has already been problematic because the U.S. doesn’t recognize the Taliban, and holds the government’s funds,” Abu Haniyeh said.

“There may be consequences for this view in the long term.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.