DALLAS — Rayenieshia Cole did not want another child. She couldn’t afford it.

A single mother who made her living dancing at a strip club, she had few relatives in Texas to help raise her three boys.

When Cole learned she was pregnant last fall, she visited an abortion clinic, where she passed an ultrasound screening — Texas had just enacted a law prohibiting abortion after about six weeks — and made an appointment to return the next day to end her pregnancy.

As Cole was leaving the clinic, several antiabortion activists approached. They directed her to a nonprofit a couple of hundred yards away called Birth Choice, which they said could help her financially — if she chose to keep the baby.

Cole had never heard of a pregnancy center. Curious, she walked over and was struck by how the staff did not judge her.

The Future of Abortion

This is one in a series of occasional stories about the state of abortion as Roe vs. Wade faces its most serious challenge.

“They were really willing to help. They had a lot of resources,” said Cole, 27. “Housing resources, helping you get a job resources.”

In March, she gave birth to a son, Kanye, three months premature. Birth Choice provided a car seat, stroller and other items and promised continuing support for three years.

Pregnancy centers vary in what they offer and their religious affiliations, but they have the same goal: persuading “abortion-minded” women to reconsider and supporting those who continue their pregnancies.

If Roe vs. Wade falls, low-income women will suffer most. Texas offers a preview.

Abortion rights advocates accuse the facilities — which they often refer to as crisis pregnancy centers — of deceiving women by setting up shop next to abortion clinics and dressing staff in doctors’ coats and surgical scrubs despite being exempt from medical standards of care and monitoring.

“The state calls them pregnancy resource centers,” said Dr. Bhavik Kumar, staff physician at the Planned Parenthood Center for Choice in Houston. “I call them state-funded fake clinics.”

He said the centers don’t provide enough financial support or address the many other reasons that women seek abortions.

“Simply providing diapers and baby clothes is not going to make this go away,” Kumar said. “This is years of caring for people and probably the children they have at home.”

The first center opened in 1967 in a home in Hawaii as the movement to legalize abortion was gaining momentum. Today they operate as nonprofits in every state, with more than 2,500 centers nationwide — about triple the number of abortion clinics. Most belong to one of four Christian antiabortion networks.

The Associated Press recently found that 13 states have spent $495 million since 2010 to help fund the centers — including at least $89 million this fiscal year.

That is expected to grow if the U.S. Supreme Court overturns Roe vs. Wade, a ruling expected this month that could lead to abortion in effect being banned in 26 states.

“We pray for an end to abortion. We hope that day will come,” said Ronda Kay Moreland, chair of Birth Choice’s board. “But that won’t put an end to the need for what we do. We’re going to be inundated, and if anything, we’ll need to grow our services.”

As tensions build over the looming court decision, pregnancy centers are finding themselves facing backlash.

Since a draft opinion overturning Roe was leaked last month, centers in New York, Maryland, Ohio, Washington, Wisconsin, the District of Columbia and a Dallas suburb have had windows smashed and been set on fire and splashed with red paint.

They were also tagged with messages that included “Forced birth is murder” and “If abortion isn’t safe, you aren’t either” — a signature slogan of an abortion rights group called Jane’s Revenge.

Moreland said Birth Choice has consulted with local police and increased security ahead of the Roe ruling.

“Anyone associated with the pro-life movement needs to practice good safety measures now more than ever,” she said.

::

Texas has about 200 pregnancy centers — more than any other state — and over this year and the next will spend $100 million on them, a total that includes some federal welfare dollars.

Birth Choice received $116,000 in state funding this year.

“We’re blessed to live in a state that does have an active approach,” Moreland said. “I mean, the state of Texas is giving, providing financial support and resources.”

The rest of the center’s budget — roughly $500,000 — comes from private donations and grants.

Moreland, executive producer of a local conservative talk radio show, said she supports Birth Choice because she was adopted in the fall of 1974, less than a year after Roe.

“My birth mother could have chosen to have me aborted,” she said. “I had a really good life, so I do this to give back.”

“We pray for an end to abortion. We hope that day will come. But that won’t put an end to the need for what we do.”

— Ronda Kay Moreland, chair of Birth Choice’s board

Started by a local Catholic activist, Birth Choice opened in 2009 in the same office complex as a new abortion clinic, the Southwestern Women’s Surgery Center. Moreland said the goal was “to have a last line of support next door.”

Some of the regular protesters in the parking lot handing out antiabortion pamphlets and rosaries belong to the Catholic Diocese of Dallas. While they don’t have a formal affiliation with Birth Choice, staffers call them “sidewalk counselors.”

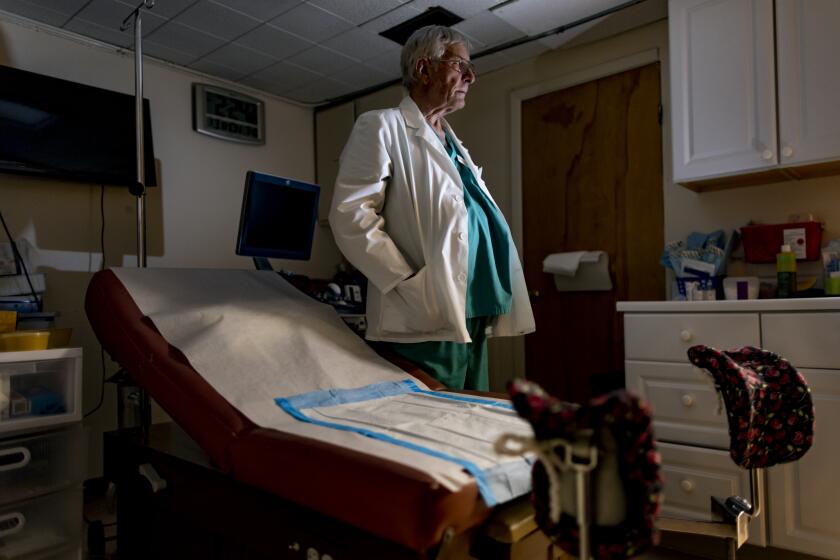

Located in a second-floor office near an accountant and a spa in a sprawling middle-class neighborhood, the center has nine employees, including two nurses. It offers counseling, pregnancy tests, ultrasounds and other services aimed at helping women through pregnancy and early motherhood.

Some assistance comes without strings, but the women they help can get more by using “baby bucks” they earn by attending classes.

Moreland said the center sees about 1,000 women a year and over the last dozen years has prevented at least 2,000 abortions.

Ahead of an expected Supreme Court decision on Roe vs. Wade, medication abortions have surged — and drawn the interest of opposition groups.

The center belongs to Heartbeat International, a nonprofit founded in 1971 that describes itself as an “interdenominational Christian association” that aims “to reach and rescue as many lives as possible, around the world, through an effective network of life-affirming pregnancy help.” It claims more than 3,100 affiliated centers in 80 countries.

In a recent speech at the group’s annual conference this spring, the group’s general counsel, Danielle White, spoke proudly of a brief she filed in the abortion case now before the Supreme Court.

“I had the distinct honor and opportunity to tell the court women don’t need abortion,” she said. “Because I know what we know here in the pregnancy help movement: That we are here for them.”

It’s unclear how many women have been denied access to abortion because of the new Texas law banning the procedure after detection of fetal cardiac activity — usually at about six weeks of pregnancy. But some have ended up at Birth Choice.

Last fall, after an ultrasound showed one 27-year-old was too far along for an abortion under the new law, she was directed to clinics in New Mexico, more than 700 miles away.

She didn’t have a car and had never traveled out of state.

“I’m thinking, how am I going to go to New Mexico?” said the mother of three, who had fled domestic violence and spoke on condition that she not be identified. “I couldn’t hold back my tears.”

She was leaving the clinic with her sister when one of the Catholic “sidewalk counselors” approached with a message: “You are not alone.”

Birth Choice connected the woman with Blue Haven Ranch, a maternity home opened last year by an evangelical couple in a Dallas exurb. They gave her and four other women — and their children — their own apartments for free during their pregnancies and as they recover after giving birth.

“Imagine the feeling of being somewhere safe,” said the woman, who is studying online to become a certified bookkeeper.

Her baby, a boy she plans to name Cason, is due Wednesday. The family can stay at the ranch for up to 18 months after she delivers.

Aubrey Schlackman, who runs the ranch with her husband, recently threw her a baby shower and is raising money to get her a used van.

For Schlackman, being “pro-life” is about not only banning abortion but also helping mothers.

“If Roe vs. Wade really is overturned, every state is going to have to deal with that same issue,” she said. “There’s going to be a lot of need, and a lot of people looking for options.”

::

In 2018, public health researchers at the University of Georgia launched a project to track and map crisis pregnancy centers.

“It’s a very critical time to be looking at what CPCs are doing, where and how they may change as the policy landscape changes,” said Andrea Swartzendruber, an epidemiologist who leads the initiative.

Among her biggest concerns is that many centers have been changing their names to include the words “medical” or “clinic,” creating the impression they are medical professionals when that is often not the case.

“As states provide restrictions or bans, they’ll fund crisis pregnancy centers,” she said. “It worries me that they’re looking like medical services, and that could slow people down or delay them from care.”

While about 77% of the centers offered free ultrasounds last year — up from 66% in 2018 — Swartzendruber said she fears nonmedical staff may not properly interpret or explain the results.

Pregnancy centers are also expanding services that she said are not backed by science, most notably the idea that medication abortions can be reversed using the hormone progesterone — a strategy that has been discredited by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Robin Sikes, a counselor at the abortion clinic in the same office complex as Birth Choice, said she has seen patients who had received inaccurate ultrasounds there.

Others who visited the center relayed to her that they were told — falsely — that abortion could lead to death, cause infertility or increase the risk of breast cancer.

She also finds it hard to accept the way the center’s name plays on “pro-choice,” which she sees as a deliberate attempt to lure women seeking abortions, with the activists on the sidewalk “intentionally trying to mislead and misdirect them.”

Despite all that, Sikes described the relationship between the abortion clinic and the pregnancy center as “cordial.” Their staffs rarely interact except when they accidentally receive each

other’s mail.

Aaron Fowler, the executive director of Birth Choice, said that the ultrasounds it performs are accurate and that the center doesn’t pose as a clinic or try to manipulate or misinform women: “Under no circumstances does my board, my staff, myself or volunteers misrepresent to clients what the opportunities are here.”

::

While some pregnancy centers provide only short-term support, Birth Choice prides itself on helping women for up to three years after they give birth.

Tequila Brown, 33, who has lupus and is bipolar, is still receiving support two years after the birth of her second son, Levi.

Brown discovered Birth Choice when she was pregnant with her first child — 4-year-old Ezekiel — and working as a call center supervisor.

“My company was really good to me until I got pregnant,” she said. “The first day of my third trimester, I got fired.”

She also lost her health insurance. So Brown researched pregnancy centers online, came to Birth Choice for an ultrasound and returned for parenting classes, supplies and counseling.

“Like family, they embraced me,” Brown said. “Their objective is to uplift single mothers, women that are pregnant, and just make sure that their self-esteem stays intact, their spirituality stays intact.”

After each consultation with a client, some employees pray at the center’s chapel before an altar surrounded by portraits of the Virgin of Guadalupe, Pope John Paul II and Gianna Beretta Molla, an Italian saint who died in childbirth.

Others are drawn to the chapel by the daily tolling of a bell, signaling afternoon prayer.

A dozen staff members knelt in chapel pews one day last month as a colleague led them in a prayer “for the courts and for the protection of the unborn.”

“We pray that our laws will protect their right to life, and that the decisions of our courts will uphold those laws and preserve that protection,” she said.

More from 'The Future of Abortion'

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.