HOLLAND, Mich. — Growing up in this small town near the western edge of Michigan, Christy Berghoef learned to live by a simple rule.

“To be Christian is to be Republican is to be ‘pro-life,’” she said recently, sitting in a renovated shed-turned-office behind her house on the 40-acre farm of willows and gladiolus where she was raised. “All else makes you a ‘baby killer.’”

Berghoef abided those harsh judgments. As a child, she prayed for abortions to end. In her teens, she marched in antiabortion vigils and carried signs at protests. After college, she found a job on Capitol Hill for her Republican congressman, where she was recruited to be a legislative aide on antiabortion law.

Her politics eventually shifted even as her faith stayed firm. She switched her voter registration to Democratic. Her definition of “pro-life” expanded to tightening gun control and protecting the rights of immigrants. She now believes — in what is considered sacrilege in the wood church where she was raised in the Midwest — that abortions should never be outlawed, though she’d rather see fewer of them.

In a city of 33,000 that’s home to nearly 200 churches and where “Pray for the unborn” billboards are as common as campaign signs in a presidential election year, Berghoef, a worship leader at a liberal church where her husband pastors, is part of a new, if disconcerting, breed of Christians challenging the teachings of their elders.

The Republican Party, evangelical Christianity and the antiabortion movement have been inextricably joined in a battle that for the last five decades has shaped the contours and passions of American politics. The powerful alliance is a major reason President Trump was elected and able to shift the Supreme Court rightward.

As the nation awaits the court’s opinion in a case that could dismantle Roe vs. Wade, the ruling that guaranteed the right to abortion, Berghoef is among an increasingly vocal minority of former conservatives who have been condemned by many in their faith as supporting a grave sin.

“I wish someone had told me back when I threw all my energy into this ‘pro-life’ movement that it’s not about saving the lives of the little babies in the pictures,” said Berghoef, a 47-year-old mother of four. “It’s about politics and being on the ‘right’ side of your community.”

Americans’ views on abortion have remained relatively the same in recent years. About 59% believe it should be legal in all or most cases, according to the Pew Research Center. Conversely, roughly 39% want it to be illegal in all or most circumstances. Opposition is strongest among white evangelicals, among whom 77% oppose abortion in nearly all cases.

In the town of Holland, that percentage can feel even higher. “Abortion is morally wrong in any case!!! No argument!!” one person commented on Facebook in reply to one of Berghoef’s many postings touching on the subject. It’s a tone she’s become accustomed to.

The Future of Abortion

One in an occasional series of stories about the state of abortion as Roe vs. Wade faces its most serious challenge.

As a regular contributor to the local newspaper, she’s learned that describing her stance as “broadly pro-life” will get a reaction. “The way people fight for abortion shows they are very ‘pro-abortion,’” said one letter to the editor criticizing her.

Private messages from conservative Christians have been harsher, calling her a “murderer.”

Berghoef, who grew up in the Christian Reformed Church, is in a corner of a traditionally conservative community taking a different stance. As a former Republican activist, she also believes she can be a bridge between bitterly opposing sides as the nation anticipates the possibility of a post-Roe landscape that could further divide Americans and outlaw abortion in as many as 26 states.

“One of the most frustrating things for me on this issue of abortion is that it’s described as if ‘It’s my body, my choice and I can do whatever I want,’ or you are seen as ‘murdering babies’ if you are ‘pro-choice,’” Berghoef said. “Those are your two options. I reject both.”

Raised on a farm and transformed by city life, Berghoef, whose elongated vowels thread an upper Midwestern accent, at once fits in with the culture of Holland and stands out. She often sports Ugg boots over jeans with a sweater and scarf. She carries a carpenter’s tools. She recently finished gutting and renovating her kitchen with concrete countertops and wooden shelves. In her backyard, she’s rebuilt a small Civil War-era shed she found on Craigslist, turning it into an office and reading space.

Berghoef descends from Dutch immigrants who moved to the Dakotas in the 19th century and later relocated to this Michigan town. The conservative Dutch faithful came to the frigid Midwest in search of religious freedom. Today, the Holland area is dominated by the Christian Reformed Church and its cousin, the Reformed Church in America. Streets and cities are named after Dutch originals. Downtown, a park with a Dutch windmill and tulips attracts tourists each spring.

Ottawa County, where Bible verses mingle with talk radio and Trump won with 60% of the vote in 2020, is one of the most reliably Republican counties in the state. It’s also among the least diverse — 83% of the population is white. While the Southern Baptist Church dominates the Bible Belt and is the largest evangelical denomination in the nation, Reformed churches — those in western Michigan in particular — have long been a powerhouse of conservative Christian thought and politics.

It’s the world where Berghoef attended a Christian school, signed a “pro-life pledge” and went to church each week. On Sundays, stores were closed for the Sabbath and bike rides were discouraged. At services, Berghoef remembers politics rarely coming up, she said, “except that we absolutely would never support abortion and would vote ‘pro-life.’”

To a young Berghoef, the hand of God was intrinsic to everyday existence. But one had to be ever watchful for acts of evil.

Conservative statehouses are dropping rape exceptions from abortion bans as they look ahead to the Supreme Court’s expected decision in a major abortion case.

“If a woman had an abortion, we called her a murderer,” she said. “Doctors who performed abortions were murderers with no respect for life.”

It was an uncompromising world, she said, “with little room for nuance.” For a child, the “simplicity was easy to embrace.”

Her passion for stopping abortions led her to study political science at Calvin University in nearby Grand Rapids. After graduating in 1999, at a time when more states were moving to restrict abortions, she joined the office of Republican Rep. Peter Hoekstra in Washington, D.C.

“I wanted to push these laws that would make abortion illegal because I wanted to protect the unborn,” Berghoef said.

But in the nation’s capital, she saw homelessness and poverty on her walks to work. She reflected on the parables and teachings of her youth and wondered how her focus on abortion was helping those whom Jesus described as “the least of these.” In conversations with members of Congress, she said, she was shocked to hear talk of abortion as a political issue instead of a moral one. While responding to constituent letters, Berghoef researched data on abortion.

She felt herself changing. She wondered whether she had been naive in believing that her fight saved souls and lives. Such questions were a challenge to her faith and identity.

“I started to realize that the thing that’s actually going to bring down this abortion rate is all these things that my party, the Republicans, were working against: affordable healthcare, access to contraceptives, expanded availability of child care and better educational opportunities for women.”

“I felt like I could no longer be a Republican. I didn’t want to be a Democrat,” Berghoef said, remembering that pivotal moment years before casting her first vote as the latter. “I became a political nomad.”

She returned to Michigan and enrolled at Calvin Theological Seminary in Grand Rapids, where she met her now-husband, Bryan, an aspiring pastor on a similar journey.

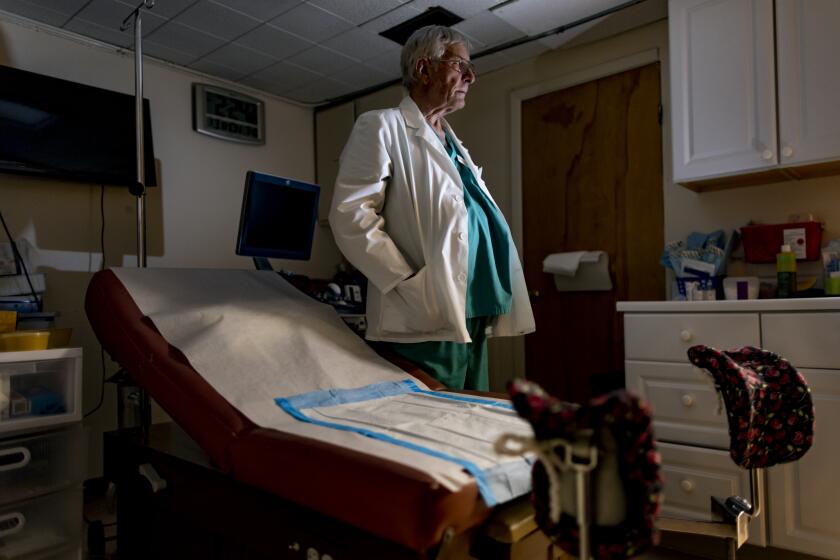

With the Supreme Court expected to rule on Roe vs. Wade in the coming months, a Colorado abortion provider has recommitted himself to what he says is his life’s work: helping women.

Over two decades, they launched small churches in Traverse City, Mich., and Washington. She found a part-time job at the Faith and Politics Institute, a group whose mission is to bring together politicians on both sides of the aisle.

Her spirituality remained the same. Her politics veered leftward.

But something felt off. D.C. wasn’t home. Being progressive church planters was difficult in a big, liberal city, where for many, picking a house of worship seemed like shopping at a department store. It also wasn’t easy to support a family of six on part-time jobs while running a new church. The lease to their house was running out. And their son, who had severe dyslexia, wasn’t getting the care he needed in school — something that was readily available back home in Michigan.

God was telling the family it was time to go.

The return to the Midwest was a delicate one. The family moved to Holland in 2014, settling in a small house on the same plot where Berghoef grew up. Her dad, who remains a conservative, antiabortion Christian, still lived on the property, where he tended to his flower farm. The old bonds of love were as strong as the new divides of politics.

“Like us, they’re passionate about following Jesus,” she said. “But we have very different experiences in the world. Some of my family members have just lived here their whole life. They’ve never left. This is the world they know.”

More settled in her liberal views, Berghoef made waves in the tightknit community with her Facebook postings and articles in church journals and the local paper.

“At the risk of angering my friends who lean progressive, I will admit I personally consider myself broadly pro-life (from the womb to the tomb),” she wrote in one piece. “At the risk of confounding my friends who lean conservative, the evidence does not reveal that the most effective way to reduce abortion in this country is to simply overturn Roe vs. Wade, but rather to examine who is having abortions and why, and work at those things.”

Her middle-of-the-road statement and other opinions — such as her stance against Trump’s first presidential campaign — were radical for Holland. Old high school friends blocked her on Facebook and refused to speak to her, describing her as supporting “baby killers.” Others reached out to her to share their secrets of undergoing abortions and hiding them out of fear of being ostracized.

A small Bible study started meeting at the Berghoef home. A community within a community began to grow. By the weekend after the 2016 election, it was a church with its own rented hall. Christy and Bryan had left their denomination for the more liberal United Church of Christ.

Today, Holland UCC, as it’s called, attracts a variety of ex-conservative Christians and a few agnostics. One of the few local churches open to LGBTQ Christians, its members have also marched in Black Lives Matter demonstrations. The logo on the church‘s website is a white comma over a rainbow circle, a reminder to never “put a period where God has placed a comma, because God is still speaking.”

But abortion remains a most potent subject, one millions of conservative Christians see as indivisible from their faith.

“I don’t think many in our community would support making it illegal, but we come in with different views,” said Bryan Berghoef, who lost a Democratic bid for Congress in 2020 and was mocked by other Christians for not being “pro-life” enough. Some in Holland questioned how a man could be both a pastor and a Democrat.

“We welcome people in however they are and whatever they believe, wherever they are on their journey,” he said, thinking of the long road to where he is today.

Over the years, the church has led the annual Women’s March in Holland. But last year, after the Texas Legislature passed a law allowing civil lawsuits against people who indirectly aid in abortions — such as Uber drivers — Holland UCC decided to not officially take part in the protest march formed in response.

The gathering, in the hundreds, was large for Holland, though nowhere close to the size of the crowds at antiabortion events. A church member who was a survivor of rape was among the organizers. The Berghoefs, who were not in town at the time, said they would have joined as long as they were not representing the church.

In the spruced-up shed in their backyard, the couple have created an informal community space for likeminded individuals to come together over craft beers and Michigan wines. During the waves of the pandemic when the church met only online, it’s where he broadcasted sermons and she played guitar to lead worship songs with titles such as “I Want Jesus to Walk With Me” and “Change My Heart Oh God.”

On a recent chilly spring evening, a few church members and fellow Christians had come to the shed to swap stories with Christy Berghoef over what it meant to be “pro-life” and “pro-choice.” Some were Holland UCC members. Others were part of more traditional faith communities.

Judy and Scott Vander Zwaag had joined the church several years ago after spending much of their adult lives in a conservative Holland congregation. Former Republicans, they had crossed political aisles — and denominations — later in life.

“I feel bad about how I treated others in the past and the things I said or did when it came to being ‘pro-life’ or ‘pro-choice,’” Scott Vander Zwaag said. He had spent years as an elder in his former church. His duties included determining who wasn’t following church teachings on sex and marriage.

The group spoke of how abortion wasn’t always a Republican issue. Up through the 1960s, conservative Christians advocated for the right to abortion as a matter of separation of church and state. Then, in response to the civil rights movement, which fractured old Democratic alliances, evangelical leaders launched the “pro-life” movement as a political strategy to unite voters.

They also discussed how Michigan was one of the states where a law banning abortion in nearly all cases was already on the books, dating to 1931. If Roe were overturned, the legislation may apply once again.

Kris and Vern Swieringa, who were still members of the Christian Reformed church — Vern pastored one about 30 minutes away — were also in the shed.

“Personally, I’m against abortion,” Kris Swieringa said. “But making a law won’t make something go away. I look at these groups against abortion and they don’t care about rape or incest or when a mother is in danger. They just want to make abortion illegal. Republicans are so much about a child before it’s born. But what laws do they pass to help a child after it’s born?”

A close friend, she said, had recently had an ectopic pregnancy — where the fertilized egg implants outside the uterus, usually in one of the fallopian tubes — and required an abortion.

Berghoef guided the conversation, at once speaking like a counselor, friend and pastor.

“The things we grew up with in the church are the same things that make us question some of its positions now,” she said. “We were taught to be loving, truthful, serve our communities and seek justice the same way Jesus did.”

Each had lost friends and at times family for speaking out on abortion or politics. To them, it was the right thing to do. The Christian thing to do.

More from 'The Future of Abortion'

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.