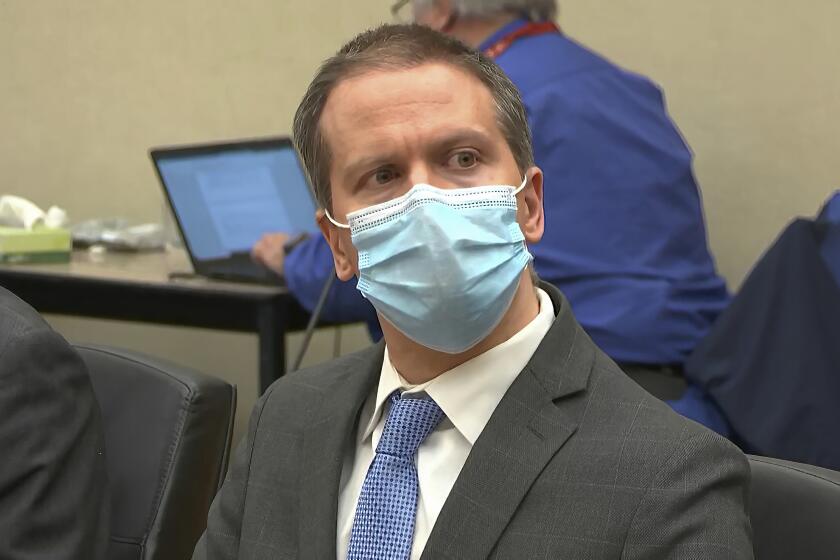

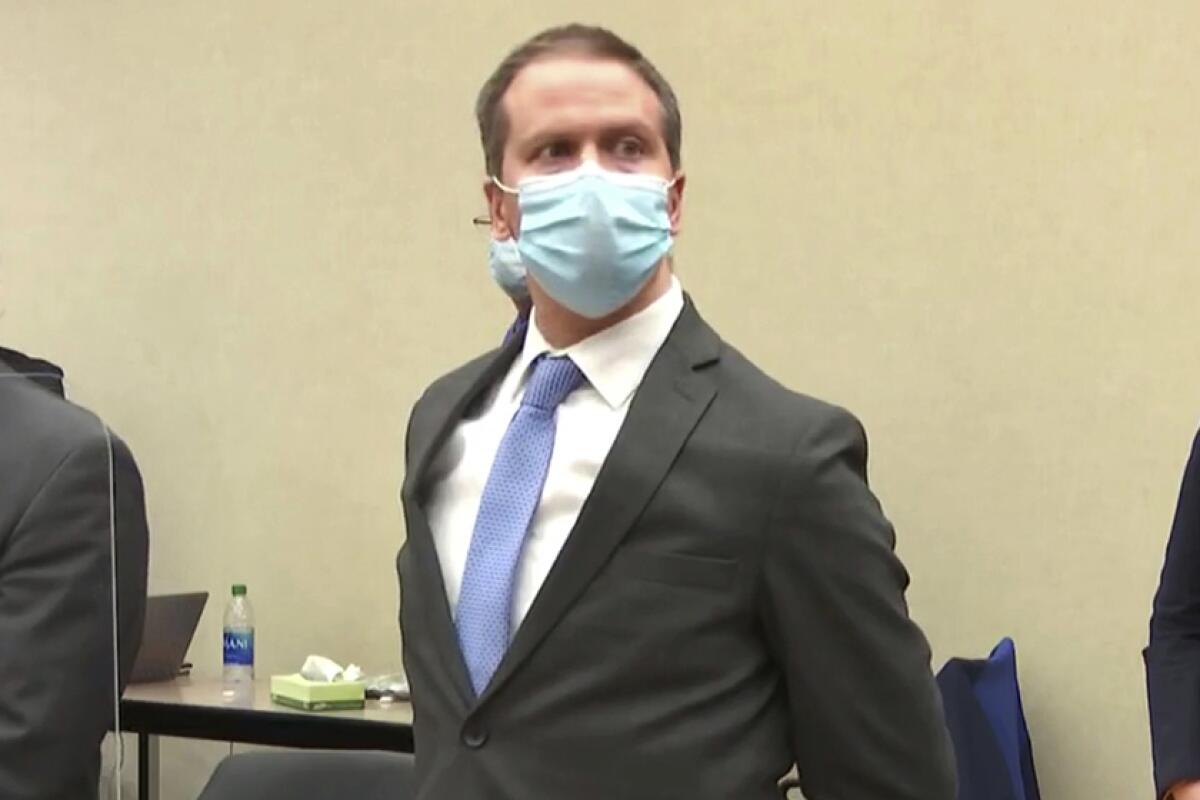

Derek Chauvin faces sentencing for the murder of George Floyd

MINNEAPOLIS — Former Minneapolis police Officer Derek Chauvin learns his sentence Friday for murder in George Floyd’s death, closing a chapter in a case that sparked global outrage and a reckoning on racial disparities in America.

Chauvin, 45, faces decades in prison, with several legal experts predicting a sentence of 20 to 25 years. Though Chauvin is widely expected to appeal, he also still faces trial on federal civil rights charges, along with three other fired officers who have yet to have their state trials.

The concrete barricades, razor wire and National Guard patrols that shrouded the county courthouse for Chauvin’s three-week trial are gone, and so is most of the tension in the city as it awaited a verdict in April. Still, there’s a recognition that Chauvin’s sentencing will be another major step forward for a city that has been on edge since Floyd’s death on May 25, 2020.

“Between the incident, the video, the riots, the trial — this is the pinnacle of it,” said Mike Brandt, a local defense attorney who has closely followed Chauvin’s case. “The verdict was huge too, but this is where the justice comes down.”

Chauvin was convicted of second-degree unintentional murder, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter for pressing his knee against Floyd’s neck for about 9½ minutes. Floyd, who was Black, said he couldn’t breathe and went limp. Bystander video of Floyd’s arrest for suspicion of passing a counterfeit $20 bill prompted protests around the world and a nationwide reckoning on race and police brutality.

The former Minneapolis police officer, 45, could receive up to 30 years in prison, experts say.

Under Minnesota statutes, Chauvin will be sentenced only on the most serious charge, which has a maximum sentence of 40 years. But case law dictates that a 30-year sentence would be the practical maximum sentence Judge Peter Cahill could impose without risk of being overturned on appeal.

Prosecutors asked for 30 years, saying Chauvin’s actions were egregious and “shocked the nation’s conscience.” Defense attorney Eric Nelson requested probation, saying Chauvin was the product of a “broken” system and “believed he was doing his job.”

Cahill has already found that aggravating factors in Floyd’s death warrant going higher than the 12½-year sentence recommended by the state’s sentencing guidelines. The judge found Chauvin abused his position of authority, treated Floyd with particular cruelty, and that the crime was seen by several children. He also wrote that Chauvin knew the restraint of Floyd was dangerous.

“The prolonged use of this technique was particularly egregious in that George Floyd made it clear he was unable to breathe and expressed the view that he was dying as a result of the officers’ restraint,” Cahill wrote last month.

Attorneys on both sides are expected to make brief arguments Friday, and victims or family members of victims can make statements. No family members have said publicly that they will speak.

Chauvin can also make a statement, but it’s not clear if he will. Experts say it could be tricky for Chauvin to talk without implicating himself in the pending federal case accusing him of violating Floyd’s civil rights.

Chauvin chose not to testify at his trial. The only explanation the public has heard from him came from body-camera footage in which he told a bystander at the scene: “We got to control this guy ’cause he’s a sizable guy ... and it looks like he’s probably on something.”

Several experts said they doubted Chauvin would take the risk and speak, but Brandt thought he would. He said Chauvin could say a few words without getting himself into legal trouble.

Retributive justice must play a role in the former Minneapolis police office’s sentence for murder. But it should not play the only role.

“I think it’s his chance to tell the world, ‘I didn’t intend to kill him,’” Brandt said. “If I was him, I think I would want to try and let people know that I’m not a monster.”

Several people interviewed in Minneapolis days before Chauvin’s sentencing said they want to see a tough sentence.

Thirty years “doesn’t seem like long enough to me,” said Andrew Harer, a retail worker who is white. “I would be fine if he was in jail for the rest of his life.”

Joseph Allen, 31, who is Black, said he thinks Chauvin should receive “at least” 30 years, and said he’d prefer a life sentence. He cited nearly 20 complaints filed against the now-fired officer during his career.

Allen said he hopes other police officers can learn “not to do what Derek Chauvin did.”

Nekima Levy Armstrong, a civil rights attorney and activist, called for Chauvin to be sentenced “to the fullest extent of the law.” She called Floyd’s death “a modern-day lynching” and predicted community outrage if Chauvin is sentenced lightly.

When asked if she would like to hear Chauvin speak, Levy Armstrong said: “For me as a Black woman living in this community, there’s really nothing that he could say that would alleviate the pain and trauma that he caused ... I think that if he spoke it would be disingenuous and could cause more trauma.”

George Floyd died in police custody on May 25, 2020, in Minneapolis. His death led to the trial and conviction of former officer Derek Chauvin.

No matter what sentence Chauvin gets, he’s likely to serve only about two-thirds behind bars presuming good behavior. The rest would be on supervised release.

He’s been held since his conviction at the state’s only maximum security prison, in Oak Park Heights. The former officer is held away from the general population for his safety, in a 10-by-10-foot cell, with meals brought to his room. He is allowed out for solitary exercise for an hour a day.

It’s not clear if Chauvin will remain there. State prisons officials said that decision wouldn’t be made until after Cahill’s formal sentencing order.

Chauvin and the three other officers involved in Floyd’s arrest are awaiting trial in federal court on charges of violating Floyd’s civil rights. No trial date has been set.

The three other officers are also scheduled for trial in March on state charges of aiding and abetting both murder and manslaughter.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.