Editorial: Don’t measure justice for George Floyd by the length of Derek Chauvin’s sentence

As a society, we demand justice for murder victims, but we can never deliver. Their lives are gone, and we are powerless to restore to them even the slimmest fraction of what they have lost. When the criminal justice system prosecutes and punishes killers, it does so not to deliver justice to victims, but to try to deliver it to the rest of society. We lock up perpetrators to protect ourselves from their further crimes, and to warn others against committing similar acts. We do it to change the killers’ attitudes and behavior, when it’s possible to do so.

But we also imprison people to impose retribution: Punishment for the sake of punishment. Retributive justice fills a need deep within the human psyche.

That need is ancient. Sacred texts and ancient myths are rich with pronouncements about the role of retributive justice — and, importantly, about its limitations. The slide into bizarrely excessive punishment is all too easy. So convicted drug trafficker Larry D. Kiel was sentenced to prison for 2,501 years (Oklahoma, 1992). Triple murderer Rigoberto Vazquez Hernandez for 7,000 years (Texas, 2013). Child rapist Charles Scott Robinson — 30,000 years (Oklahoma, 1994). That’s 300 centuries in prison, in a nation that has existed for just under two and a half.

These gratuitous sentences and others like them have nothing to do with society’s legitimate desire for safety, order or even justice. Those convicted criminals were each sentenced to multiple lifetimes in prison as an expression of our hatred and fear.

A sentence of a single lifetime in prison, obviously, would have been enough.

But for most killers, is even that too much? A growing body of evidence suggests that people convicted of murder acted in the spur of the moment and are extremely unlikely to commit that crime again, or any other (while people convicted of petty crimes are most likely to recidivate). And if that’s the case, why keep them behind bars?

We have come to measure justice for victims in the number of years their killers spend behind bars. But, again, prison sentences are not mostly about the victims. We should measure justice instead in public safety, plus a modest measure of retribution, tempered by mercy.

There is an ongoing debate among criminal justice reformers about the appropriate maximum length of a prison sentence, even for murder. Many reject life in prison and argue for 20 years, maximum. Others for 15.

It is generally the reformers, liberal and conservative alike, who press to shorten sentences and who must be reminded of society’s need for some measure, however modest, of retributive justice. And it is usually the tough-on-crime advocates — again, both liberal and conservative — who decry reforms and push for the longest obtainable sentences.

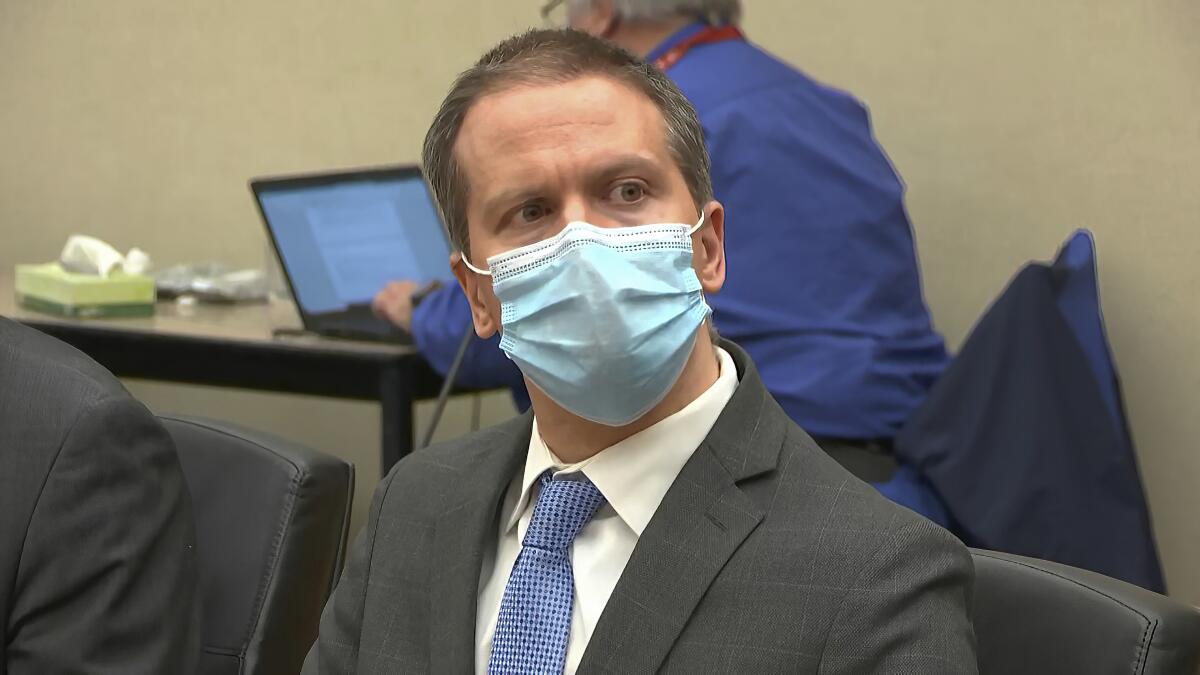

Now we face a counterintuitive test case. Former Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin, convicted April 20 of last year’s murder of George Floyd, is due to be sentenced Friday.

Chauvin, 45, could get 40 years. Prosecutors have asked for 30. Defense lawyers want probation.

The nation breathed a sigh of relief when the jury convicted Chauvin because the crime, caught on video and replayed countless times, was so evident and so brutal: He crushed Floyd’s life out by kneeling on his neck for nine and a half minutes. Failure to convict would have been an indictment of the American system of justice. The intensity of anger, and its manner of expression, would have been hard to predict (although it’s essential to remember that the only legitimate reason to convict him was his guilt, not fear of the public reaction had he been acquitted).

Chauvin is no longer a police officer and will never again be in a position to arrest a suspect with deadly force under color of authority. Do we really need to keep him locked up until he is 75? 85? Is it justice to use the remainder of his life as a warning to other officers?

Nor can we simply set Chauvin free, even if he is no danger to the rest of us, and no inspiration for other officers. He committed murder, and did it in our names, on our behalf, in violation of our laws. Some measure of retribution is in order. But how much?

If 30,000 years in prison is comically excessive, then 40 years may be tragically so, for any person whose crimes are unlikely to be repeated. That’s true of the elderly men sitting in prison today for brutal crimes they committed in their teens or early 20s, when they were young and callous. It’s true, too, for killer cops. There must be justice. There need not be unremitting, lifelong vengeance.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.