What’s possible, what’s realistic: Here’s what to know about Chauvin sentencing

MINNEAPOLIS — Former Minneapolis police Officer Derek Chauvin faces sentencing Friday for murdering George Floyd, with a judge weighing a prison term that experts say could be as much as 30 years.

Chauvin, 45, was convicted in April of second-degree unintentional murder, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter for pressing his knee against Floyd’s neck for about 9 ½ minutes. Floyd, who was Black, repeatedly said he couldn’t breathe. It was an act captured on bystander video, which prompted protests around the world.

Here’s what to watch for in a hearing that could run as long as two hours:

What’s possible?

Under Minnesota statutes, Chauvin will be sentenced only on the most serious charge of second-degree murder. That’s because all the charges against him stem from one act, with one victim.

The max for that charge is 40 years, but legal experts have said there’s no way he’ll get that much. Case law dictates the practical maximum Chauvin could face is 30 years — double what the high end of state sentencing guidelines suggest. Anything above that risks being overturned on appeal.

George Floyd died in police custody on May 25, 2020, in Minneapolis. His death led to the trial and conviction of former officer Derek Chauvin.

Of course, Judge Peter Cahill could sentence Chauvin to much less. Prosecutors have asked for 30 years, while defense attorney Eric Nelson is seeking probation.

Mark Osler, a professor at University of St. Thomas School of Law, said both sides have staked out extreme positions.

The “gulf is huge between them,” he said. “I don’t think that either side is going to end up getting what they want.”

What’s realistic?

Minnesota has sentencing guidelines that were created to establish consistent sentences that don’t consider factors such as race or gender. For second-degree unintentional murder, the guideline range for someone with no criminal record goes from 10 years and eight months to up to 15 years. The presumptive sentence is in the middle, at 12 ½ years.

Cahill last month agreed with prosecutors that aggravating factors in Floyd’s death warrant going higher than the guidelines. The judge found that Chauvin abused his position of authority, treated Floyd with particular cruelty, and that the crime was seen by several children. He also wrote that Chauvin knew the restraint of Floyd was dangerous.

“The prolonged use of this technique was particularly egregious in that George Floyd made it clear he was unable to breathe and expressed the view that he was dying as a result of the officers’ restraint,” Cahill wrote last month.

Osler said Cahill’s finding of aggravating factors showed his willingness to go above the guidelines. But he said those guidelines still function like a tether, and the further Cahill moves from the guidelines, the more the tether stretches. He said a 20- or 25-year sentence is more likely than 30.

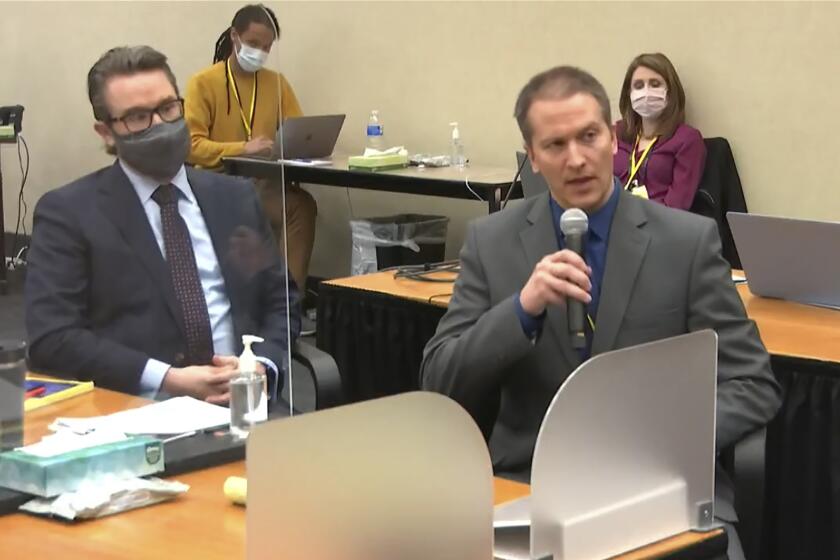

Prosecutors are seeking a 30-year sentence for the former Minneapolis police officer convicted of murder in the death of George Floyd, but a defense attorney is asking that Derek Chauvin be sentenced to probation and time already served.

Joe Friedberg, a Minneapolis defense attorney who has been watching the case, agreed. He cited a U.S. Supreme Court case, Koon vs. United States, in which the court said a judge could consider that a former police officer would probably spend much of his sentence in isolation for his own safety. Cahill might take the harder time into consideration to give Chauvin a little less, Friedberg said.

What’s happened before?

Minnesota sentencing data for the five years through 2019 show that of 112 people sentenced for the same conviction as Chauvin, only two got maximum 40-year sentences. Both cases involved children who died due to abuse; both defendants had prior criminal records and struck plea deals.

The longest sentence during that time period for someone with no criminal history like Chauvin was 36 years, in another case involving the death of a child due to abuse. The sentence was appealed but upheld, with an appellate court finding it “was not excessive when a 13-month-old child was beaten to death.”

What’s expected at the hearing?

Attorneys on both sides are expected to make brief arguments. Victims or their family members can also make statements about how they’ve been affected, but none have said publicly that they will.

Chauvin can talk if he wants, but it’s not clear if he will. Experts say it could be tricky for Chauvin to talk without implicating himself in a pending federal case accusing him of violating Floyd’s civil rights.

Mike Brandt, a defense attorney watching the case, said he thinks Chauvin will speak, and that he can say a few words without getting himself into legal trouble.

“If I was him, I think I would want to try and let people know that I’m not a monster,” Brandt said.

Community members can submit impact statements online, which may become part of the public record.

What will Cahill consider?

Cahill will look at arguments submitted by both sides, as well as victim impact statements, community impact statements, a pre-sentence investigation into Chauvin’s past, and any statement Chauvin might make.

When judges hear from defendants, they are typically looking to see if the person takes responsibility for the crime or shows remorse. Friedberg, the defense attorney, said he doubts that any statement from Chauvin would affect Cahill’s sentence.

“In state court sentencing in Minnesota, it just doesn’t seem to matter to the judges what anybody says at the time of sentencing,” Friedberg said. “When they come out on the bench they will have already decided what the sentence will be.”

How long actually behind bars?

No matter what sentence Chauvin gets, in Minnesota it’s presumed that a defendant with good behavior will serve two-thirds in prison and the rest on supervised release, commonly known as parole.

That means if Chauvin is sentenced to 30 years, he would probably serve 20 behind bars, as long as he causes no problems in prison. Once on supervised release, he could be sent back to prison if he violates conditions of his parole.

Since his April conviction, Chauvin has been held at the state’s only maximum security prison, in Oak Park Heights. That’s unusual — people don’t typically go to a prison while waiting for sentencing — but Chauvin is there for security reasons.

He has been on “administrative segregation” for his safety and has been in a 10 foot-by-10 foot cell, away from the general population. He has meals brought to his room and is allowed out for solitary exercise for an average of one hour a day.

It wasn’t immediately clear where he would serve his time after he is sentenced. The Department of Corrections will place Chauvin after Cahill’s formal sentencing order commits Chauvin to its custody.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.