Kenneth Kaunda, founding president of Zambia and foe of colonial rule, dies at 97

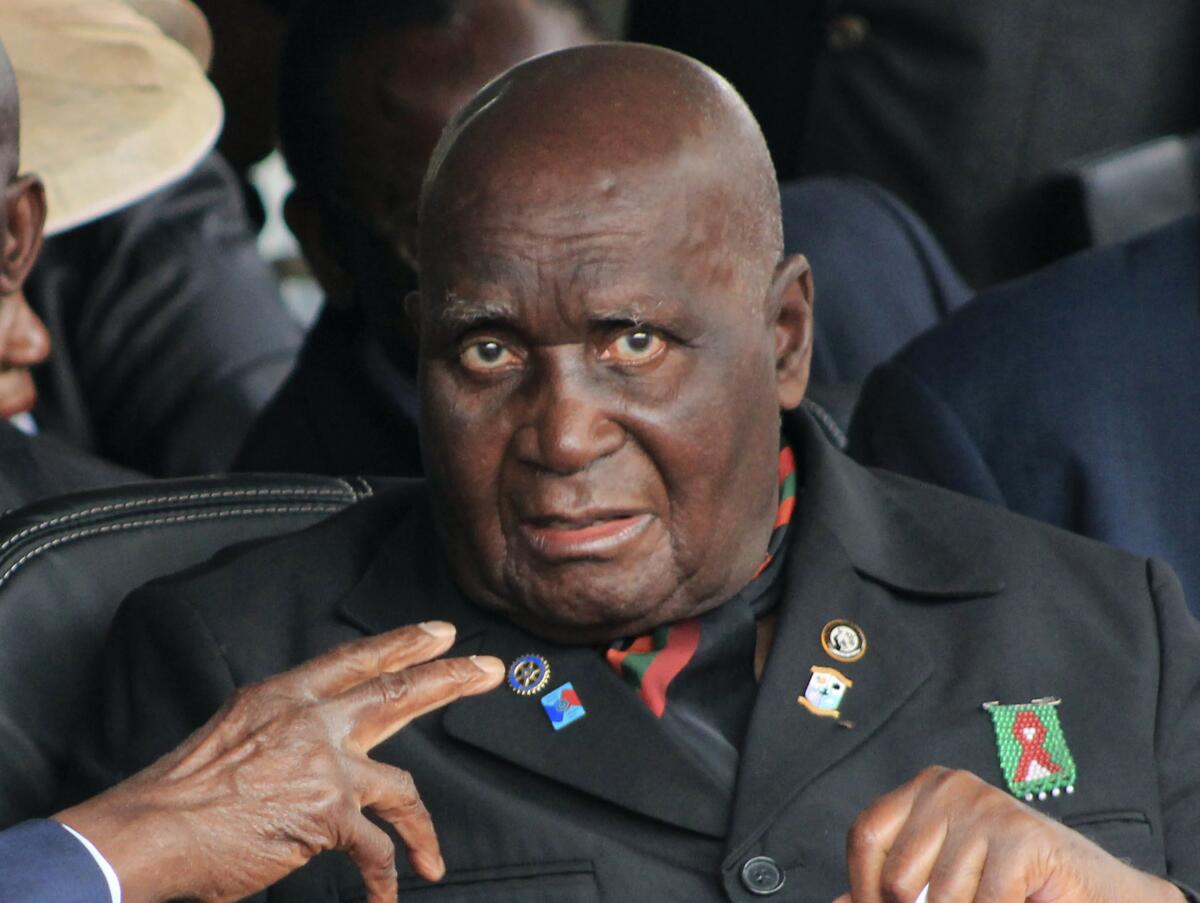

LUSAKA, Zambia — Kenneth Kaunda, Zambia’s founding president and a champion of African nationalism who spearheaded the fights to end white minority rule across southern Africa, has died. He was 97.

Kaunda’s death was announced Thursday evening by Zambian President Edgar Lungu on his Facebook page. Zambia will hold 21 days of national mourning, Lungu said.

“On behalf of the entire nation and on my own behalf, I pray that the entire Kaunda family is comforted as we mourn our first president and true African icon,” wrote Lungu.

Kaunda’s son Kamarange also gave the news of the statesman’s death on Facebook.

“I am sad to inform we have lost Mzee,” Kaunda’s son wrote, using a Swahili term of respect for an elder. “Let’s pray for him.”

Kaunda had been admitted to the hospital Monday, and officials later said he was being treated for pneumonia.

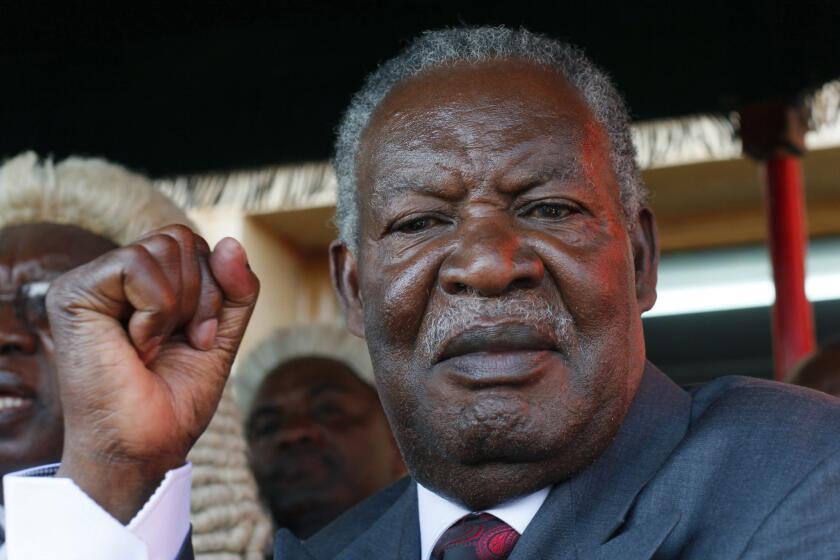

After reportedly concealing a long illness, Zambian President Michael Sata died Tuesday in a London hospital, the country’s second leader to die in office in a foreign hospital.

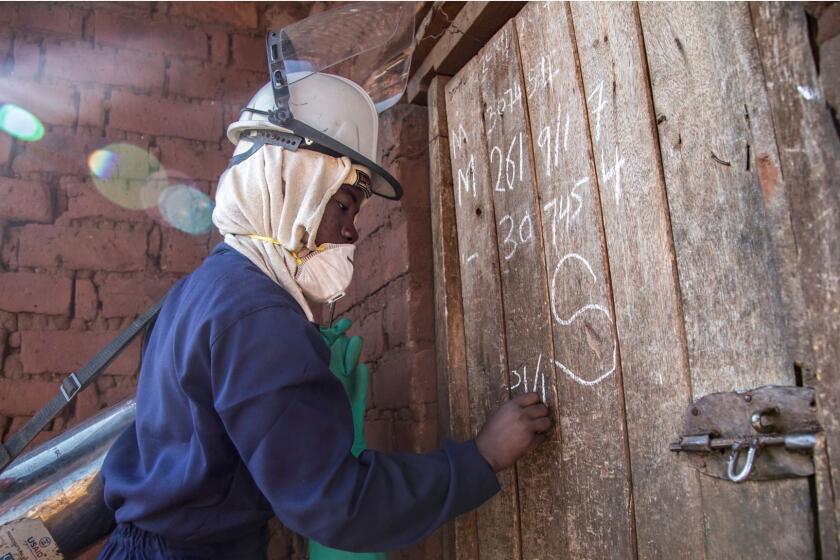

The southern African country is currently battling a surge in COVID-19 cases. Kaunda was admitted to Maina Soko Medical Center, a military hospital that is a center for treating the disease in the capital, Lusaka.

Kaunda came to prominence as a leader of the campaign to end British colonial rule of his country, then known as Northern Rhodesia, and was elected the first president of Zambia in 1964.

During his 27-year rule, he gave critical support to armed African nationalist groups that won independence for neighboring countries, including Angola, Mozambique, Namibia and Zimbabwe.

Kaunda also allowed the African National Congress, outlawed in South Africa, to base its headquarters in Lusaka while the organization waged an often-violent struggle within South Africa against apartheid.

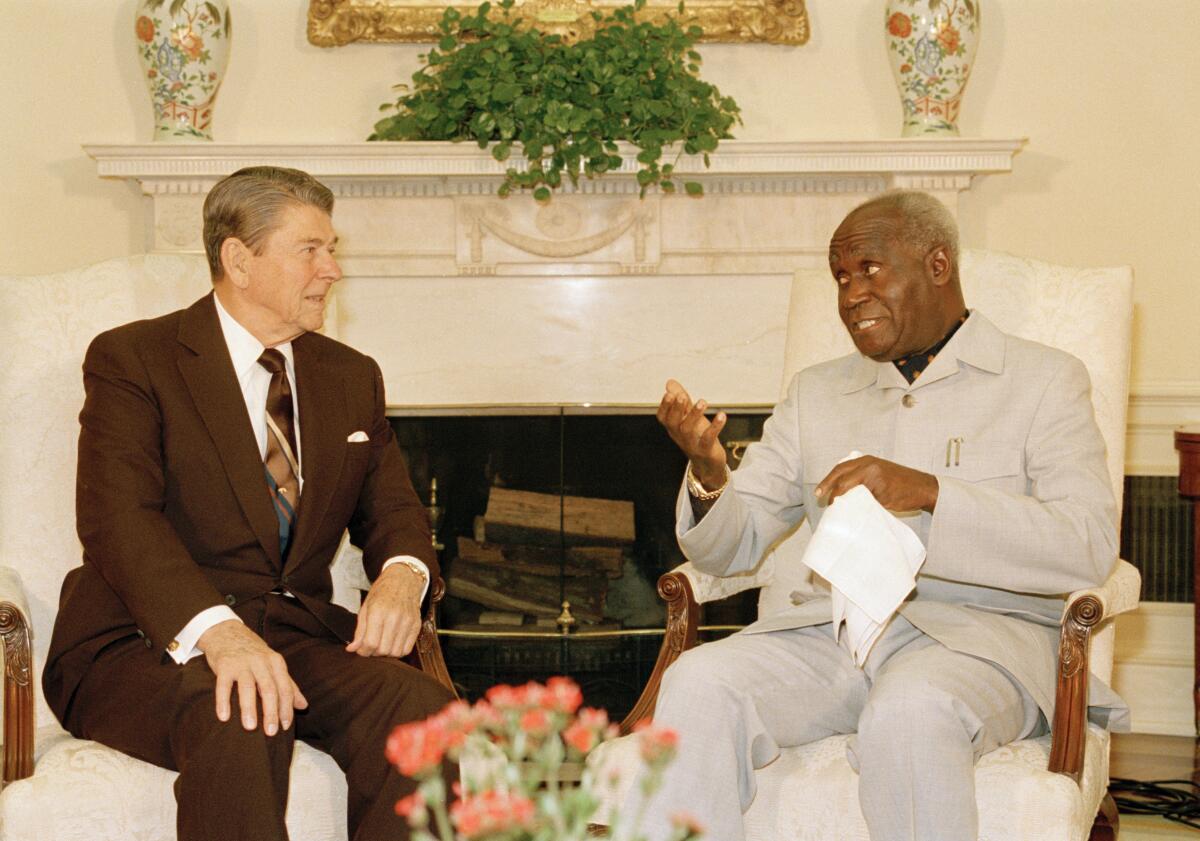

Outgoing and ebullient, Kaunda lobbied Western leaders to support majority rule in southern Africa. Famously, he danced with then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher of Britain at a Commonwealth summit in Zambia in 1979. Although he implored her to impose sanctions on apartheid South Africa, Thatcher remained a steadfast opponent of those restrictions.

Kaunda was a schoolteacher who became a fiery African nationalist. Although he eventually ruled over a one-party state and became authoritarian, Kaunda agreed to return Zambia to multiparty politics and peacefully stepped down from power when he lost elections in 1991.

In Zambia’s heady first years of independence, Kaunda rapidly expanded the country’s education system, establishing primary schools in urban and rural areas and providing all students with books and meals. His government established a university and medical school. Kaunda also expanded Zambia’s health system to serve the Black majority.

Genial and persuasive, Kaunda gained respect as a negotiator pressing the case for African nationalism with Western leaders.

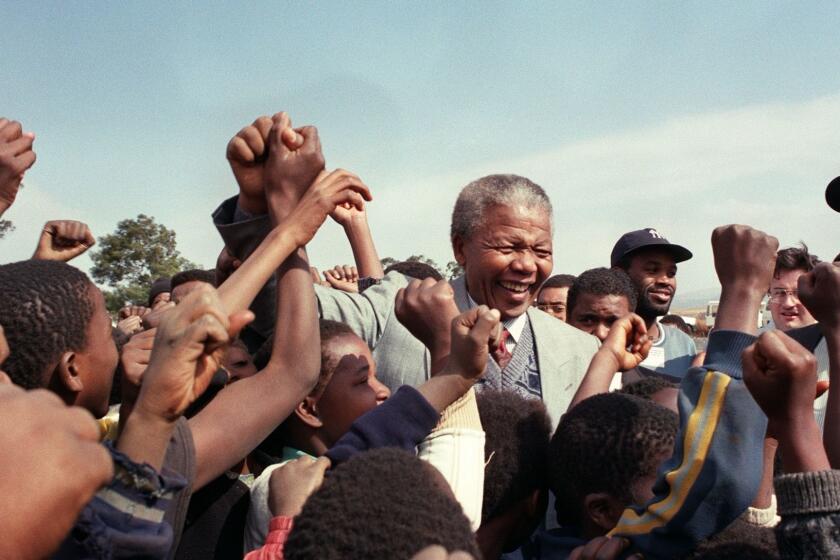

Despite domestic opposition, Kaunda ultimately conducted negotiations with the South African government that were credited with helping spur the apartheid regime to release Nelson Mandela and to allow the ANC to operate legally.

He remained lifelong friends with Mandela after the anti-apartheid leader’s release from prison, quipping that they shared the same bond of 27 years — him as Zambia’s president and Mandela as a prisoner.

Even though Zambia was not spared occasionally violent political strife, Kaunda managed to foster peaceful coexistence between its 73 ethnic groups.

Kaunda was born in April 1924, the youngest of eight children to a Church of Scotland missionary and teacher. He followed his father’s footsteps into teaching and cut his political teeth in the early 1950s with the Northern Rhodesian African National Congress.

As a Times correspondent in South Africa during the final violent spasms of the apartheid regime and the jubilant election of the country’s first black president in 1994, I noticed something odd about Nelson Mandela’s speeches.

He was imprisoned briefly in 1955 and again in 1959, and upon his release became president of the newly formed United National Independence Party. When Northern Rhodesia became independent from Britain, Kaunda won the first general election in 1964 and became the first president of renamed Zambia.

Kaunda imposed a one-party state in 1973, gradually developed a personality cult and clamped down on opposition. He said the one-party state was the only option for Zambia as it faced attacks and subterfuge from white-led South Africa and Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe).

Ruling at the height of the Cold War, Kaunda was a leading member of the Non-Aligned Movement.

Kaunda’s popularity waned as the once-thriving Zambian economy collapsed when the price of copper, its main export, plummeted in the 1970s. Corruption, mismanagement and the nationalization of foreign-owned companies and mines also contributed to the economic decline. Unemployment soared and the standard of living sank during the 1980s, making Zambia one of the world’s poorest countries.

The World Health Organization says the continent of 1.3 billion people is facing a severe shortage of vaccine as a new wave of infections is rising.

The imposition of austerity measures proposed by the International Monetary Fund and Western creditors, with whom Kaunda had a prickly relationship, led to riots over price hikes and shortages in basic commodities such as maize meal.

Kaunda eventually gave way to domestic protests and international pressure in 1990 and agreed to multiparty elections. He lost the 1991 poll to Frederick Chiluba, and the two men became bitter rivals, with Kaunda dismissing Chiluba and his allies as “little men with little brains.”

Chiluba sought to ban Kaunda, whose parents had been born in neighboring Malawi, from running again in 1996 by a constitutional amendment barring first-generation Zambians from running for president. He also used a 1997 failed coup attempt to place Kaunda under house arrest, despite the latter’s protestations of innocence. Kaunda said he comforted himself while in confinement through music and poetry, and thoughts of Britain’s late Princess Diana, who was killed in a Paris car crash in 1997.

Despite his anti-colonialist struggles, Kaunda was a self-professed admirer of Queen Elizabeth II and the British royal family. He was also an avid ballroom dancer and loved to play the guitar.

Kaunda was shot and wounded by government forces during a demonstration in 1997 and in 1999 escaped an assassination attempt. He blamed Chiluba’s allies for the November 1999 killing of his son and heir apparent, Wezi. He lost another son, Masyzyo, to AIDS in 1986.

After his retirement from politics, Kaunda campaigned against AIDS, becoming one of the few African leaders to speak up on a continent where it is often taboo. He set up the Kenneth Kaunda Children of Africa Foundation in 2000 and became actively involved in AIDS charity work. He took an AIDS test at the age of 78 in a bid to persuade others to do likewise in a country ravaged by the virus.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.