Nelson Mandela’s letters detail his 27 years as the world’s most famous political prisoner

As a Times correspondent in South Africa during the final violent spasms of the apartheid regime and the jubilant election of the country’s first black president in 1994, I noticed something odd about Nelson Mandela’s speeches.

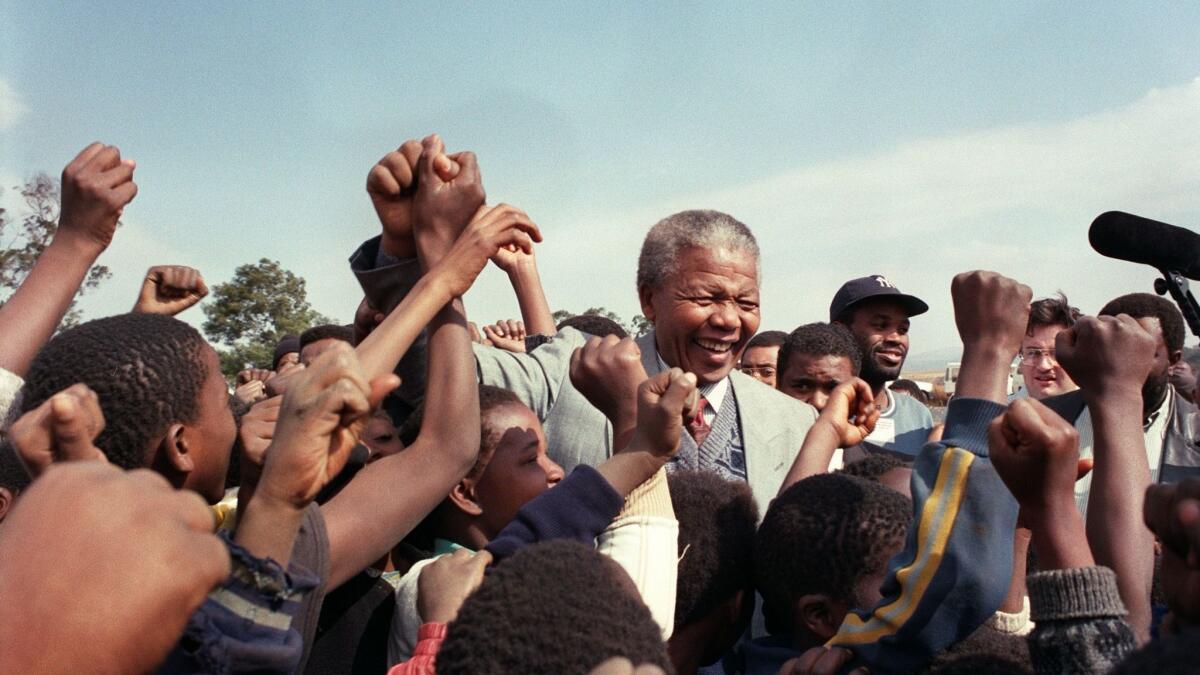

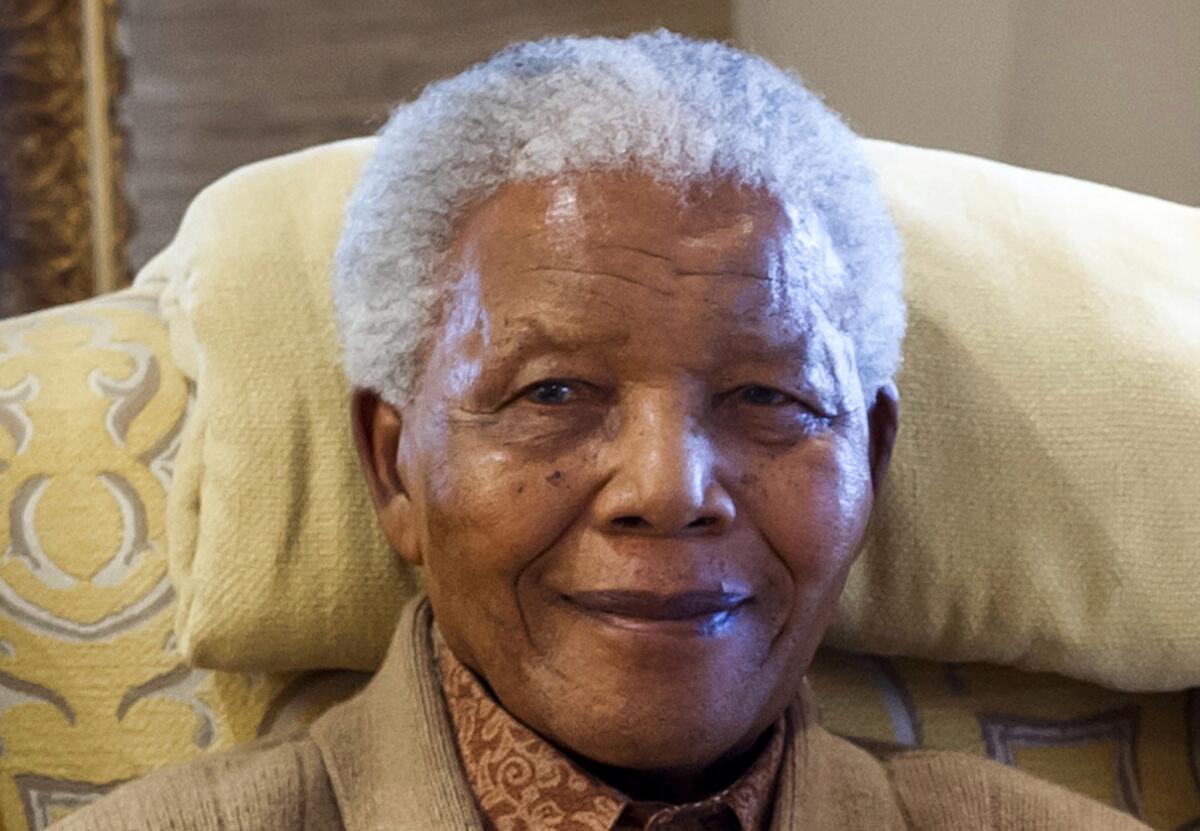

Mandela would get thunderous cheers when he took the stage. Even from a distance, the world’s most famous former political prisoner was instantly recognizable: taller and broader than most Africans, beaming his 1,000-watt smile, and always sporting one of the flamboyant “madiba” shirts designed especially for him.

But the crowd would grow restless after Mandela began to speak. He had a stilted, droning cadence that could turn an eloquent address into a reading from the telephone book. He invariably got more applause at the start than at the end. His personal and political courage was never in doubt, and his place in history — somewhere between Gandhi and Lincoln — was rock solid. But his oratory was flat.

So it was with considerable delight and relief that I read “The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela,” an astonishing outpouring from his 27 years in prison — 10,052 days to be exact. Many of the 255 letters chosen and annotated here have never been published, and because they articulate his thinking and feelings in real time, they provide a new lens to view his personal and political growth. Most of all, they help explain how Mandela survived his grueling incarceration with his passions and integrity intact.

Almost from the day he was arrested in 1962, Mandela took pen to pad and in cramped cursive wrote heart-rending missives to his wife and five children (and later numerous grandchildren), defiant letters to prison authorities and government ministers, anguished condolences to the families of fallen freedom fighters, explorations of African and colonial history, even a wistful letter about amasi, a traditional fermented milk that he desperately missed.

Underlying them all was his unfaltering optimism in the inevitability and righteousness of his cause — the end of white supremacy and democratic self-rule for the black African majority.

”Our cause is just. It is a fight for human dignity & for an honorable life,” he wrote his wife, Winnie, making clear he would never back down. Indeed, he repeatedly warned the apartheid government through the decades that it must relent, not him. Ultimately it did.

Never once did he express self-pity or regret about his plight. Instead he engaged in a drawn-out legal battle to block the government from disbarring him as an attorney (he won), pleaded for permission to attend the funerals of his mother and then his eldest son (denied both times), tried desperately — mostly in vain — to protect his wife from persecution, and advocated relentlessly for his fellow prisoners on Robben Island, South Africa’s Alcatraz, and three other prisons where he was kept.

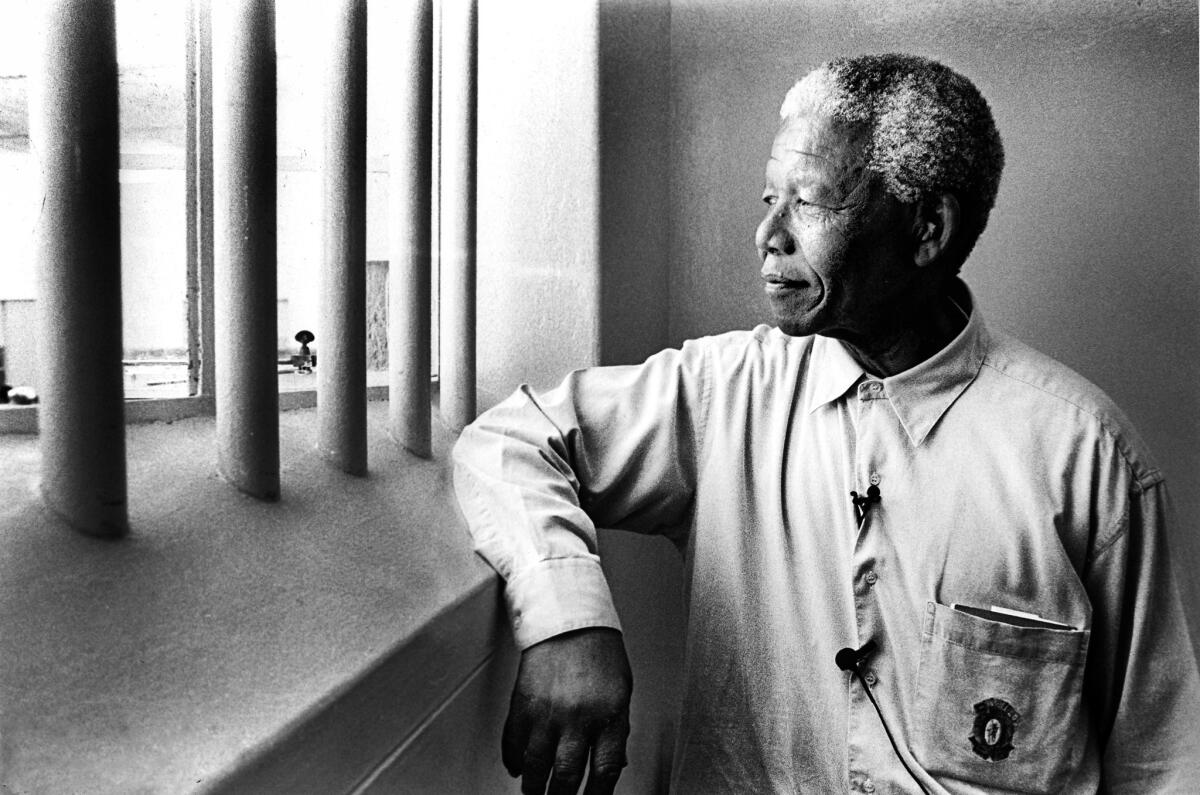

“For 13 years I have slept naked on a cement floor that becomes damp and cold during the rainy season,” Mandela noted in a 1976 letter seeking the pajamas routinely issued to white prisoners. Until the 1980s, black prisoners also were denied hot water, newspapers, radios, proper food, simple medicines and other basic amenities. “Let him blow bubbles,” an administrator scrawled derisively on one of his appeals.

For the first decade, he and other black prisoners were allowed only one family visitor every six months (children were barred until they were 16), and could send and receive only one letter of 500 words every six months. After 1973, he was allowed to write more frequently and his correspondence turned into a torrent. He also drew solace from his incoming mail, telling one friend that the messages “cut through massive iron doors and grim stone walls, bringing into the cell the splendor and warmth of springtime.”

But authorities at Robben Island maliciously censored many letters beyond recognition, or arbitrarily withheld mail and photographs. Some were found in government files decades later. Many more, perhaps hundreds, disappeared forever.

The most painful letters are those to his wife and children. In 1969, after Winnie was also arrested and jailed, he warned his two youngest daughters, Zenani and Zindzi, in unsparing terms about the hardships ahead.

“It may be many months or even years before you see her again,” he wrote. “For long you may live like orphans without your own home and parents, without the natural love, affection and protection Mummy used to give you. Now you will get no birthday or Christmas parties, no presents or new dresses, no shoes or toys.” It goes on like that for several pages.

Mandela was famously loath to speak of himself in interviews. His letters, often filled with sadness, fill out some of those details.

“I am neither brave nor bold” and have “no desire to play the role of martyr,” but am “ready to do so” if need be, he wrote. He added, almost in passing, that nearly every letter he wrote over the previous seven months had failed to reach its destination. Knowing censors would read this letter as well, he appealed to their “considerations of fair play & sportsmanship to give me a break & let this one through.” Apparently it worked.

In prison, he was always seeking to learn, taking correspondence courses and ultimately earning an advanced law degree despite a decades-long struggle to get the textbooks. But he viewed his own work with a critical eye. “I must be frank & tell you that when I look back at some of my early writings & speeches I am appalled by their pedantry, artificiality and lack of originality,” he admitted to his wife in 1970.

Locked in a cell so tiny his head touched one wall and his feet the other at night, he found ample room to praise his monk-like isolation in 1975, calling it “an ideal place to learn to know yourself, to search realistically and regularly the process of your own mind and feelings.” The deprivation, he added, “gives you the opportunity to look daily into your entire conduct, to overcome the bad and develop whatever is good in you.”

But he also escaped his dank cell by dreaming he was anywhere else. ”I never really live on this island,” he revealed in another letter that year. “My thoughts are ever traveling up & down the country, remembering the places I’ve visited.” He called a well-thumbed Oxford Atlas “one of my greatest companions.”

Perhaps the most remarkable letter is one Mandela wrote in 1976 to the commissioner of prisons. More than 20 pages long, it reads as an impassioned indictment of the rampant corruption, physical abuse and cruel indignities that black prisoners faced on Robben Island. “It is a mean type of cowardice to wreak vengeance on defenseless men who cannot hit back,” he wrote.

“It is futile to think that any form of persecution will ever change our views,” he added. “I detest white supremacy and will fight it with every weapon in my hands.”

Yet Mandela felt compelled to hold out an olive branch, one that ultimately defined his legacy.

“Even when the clash between you and me has taken the most extreme form, I should like us to fight over principles and ideas and without personal hatred, so that at the end of the battle, whatever the results might be, I can proudly shake hands with you because I felt I have fought an upright and worthy opponent who has observed the whole code of honour and decency,” he wrote.

After his release in 1990, Mandela demonstrated that grace — and his ability to forgive — by befriending several of his former Robben Island guards. His calls for reconciliation drowned out those for revenge after decades of brutal racial segregation.

Five years later, President Mandela and more than 1,000 other former political prisoners returned to Robben Island, this time as free men in a free society. I was there, and this time, Mandela’s words rang clear as a bell, clear as the letters he had penned from a bleak rocky island in the churning seas off Capetown.

“We have come to say these are the men and women who have liberated South Africa,” Mandela said. “We have come to celebrate the human spirit.”

Moments later, he trudged across the lime pit where he had done hard labor and picked up a hammer and chisel to pound a rock into shards. Other former prisoners rushed forward with hammers and pickaxes, and soon the air rang with a baritone call-and-response spiritual of freedom that wafted into the endless sky.

Drogin was the Los Angeles Times bureau chief in South Africa from 1993 to ’97.

::

“The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela”

Sahm Venter, editor

Liveright: 640 pp., $35

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.