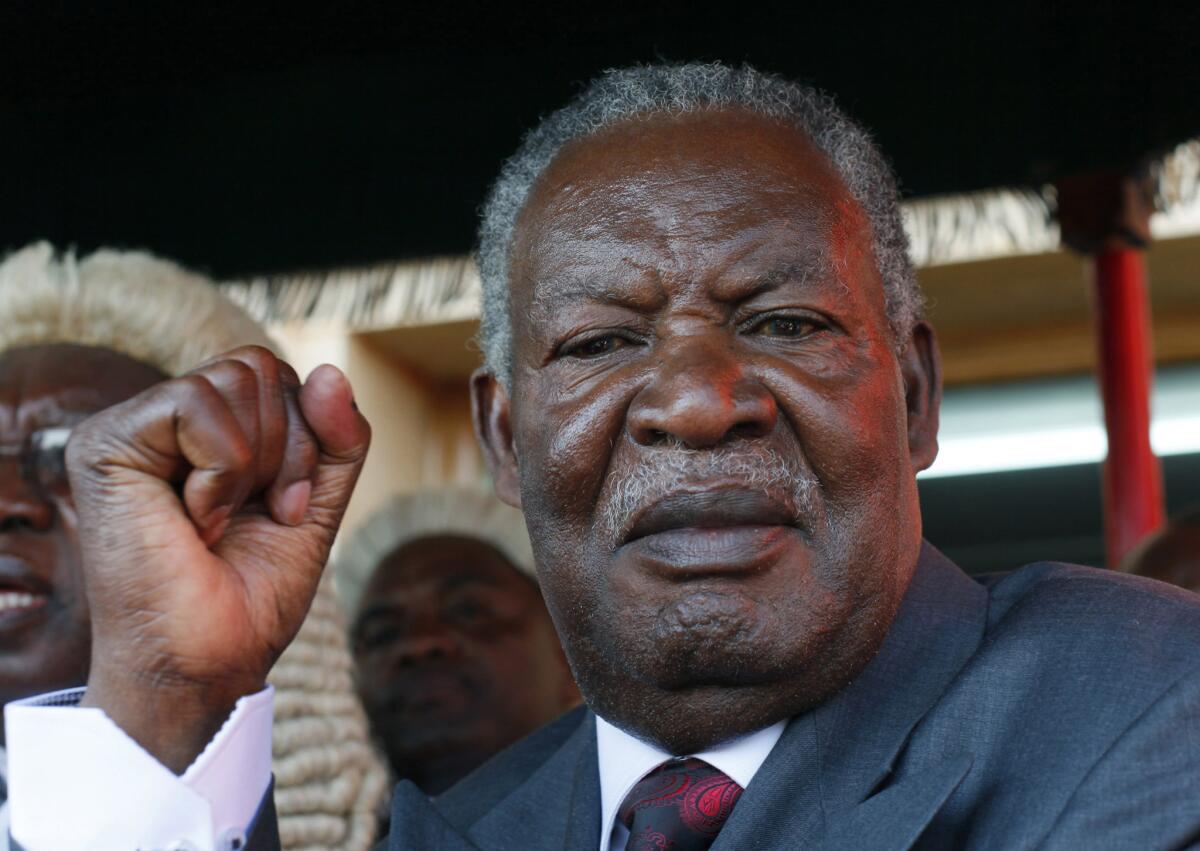

Zambian President Michael Sata dies in London after concealing illness

Reporting from Johannesburg, South Africa — After reportedly concealing a long illness, Zambian President Michael Sata died Tuesday in a London hospital, the country’s second leader to die in office in a foreign hospital.

Six years ago, then-President Levy Mwanawasa died in a Paris hospital after suffering several strokes.

The death of Sata, 77, in King Edward VII Hospital late Tuesday was confirmed by Zambia’s Cabinet secretary, Roland Msiska.

“It is with a heavy heart that I announce the passing on of our beloved president,” he said Wednesday, after media reports saying Sata was dead had surfaced.

Vice President Guy Scott was named acting president Wednesday, becoming sub-Saharan Africa’s only current white head of state.

Sata had appointed Defense Minister Edgar Lungu as acting president before departing for medical treatment in Britain. But the Zambian constitution states that when a president dies in office, the vice president becomes acting president and must call an election within 90 days.

Sata won power in the copper-producing nation in 2011, when his Patriotic Front defeated the governing Movement for Multiparty Democracy that had been in power for two decades. In one of the continent’s relatively rare peaceful and uncontested elections of an opposition presidential candidate, Sata was swept into office after campaigning heavily against Chinese abuses in the country’s copper mines.

Scott insisted last month that Sata was in perfect health, but the president had been largely out of view since May and had recently missed several important public engagements, including a scheduled address to the United Nations last month and ceremonies last week marking the 50th anniversary of Zambia’s independence.

As speculation about the president’s failing health mounted in recent months, the subject became a taboo topic for the government. Staffers last week explained his absence from the independence celebrations by saying he was undergoing a “medical checkup.” The statement announcing the health check did not indicate which country he had flown to.

He was last seen in public last month, at the opening of Zambia’s parliament, where he struggled to finish his prepared speech and abandoned it halfway through. He reportedly joked, “I am not dead.”

Lungu took his place during the independence day celebrations.

In recent weeks, a group of nongovernment organizations had called on Sata to take leave because “something is not right.” They also called on the government to come clean about his health.

In August, a group of lawyers, the Coalition for the Defense of Democratic Rights, warned that if Sata was incapable of opening parliament, that would “signify the end of the Sata presidency.”

The group said Zambians were “entitled to a president who is capable of fulfilling the duties of office according to law.” It also argued that if Sata appointed an acting president other than Scott, the government would be obliged to call a presidential by-election within 90 days.

Scott often stood in for Sata when he was absent from his duties, but questions have been raised about his eligibility to succeed Sata because of a constitutional clause stating that a president’s parents must be Zambian.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

Oct. 29, 9:35 a.m.: An earlier version of this article stated that Guy Scott was Scottish born. He was born in what was then known as Northern Rhodesia.

------------

Scott was born in Livingstone, when the country was still Northern Rhodesia, the son of a Scotsman and an English woman.

But Zambia’s Supreme Court has found in previous rulings that people who lived in Northern Rhodesia and became citizens at independence were eligible to be president because there was no Zambia their parents could have lived in before 1964.

For news from Africa, follow @RobynDixon_LAT on Twitter

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.