They escaped the worst of COVID-19. Now Cambodians face a debt crisis

PHNOM PENH, Cambodia — Phal Sokhun Sambath has not worked since mid-March, when the garment factory where she labored for $1 an hour was shuttered to help prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

Last December, she had put up the title to her parents’ house to borrow $5,000 from a bank for a family health emergency. Then came the pandemic, which wiped out her and her partner’s incomes and forced them to take out loans from their landlord, another bank, a pawnshop and a neighbor who charges 20% monthly interest.

“Every time we take out a new loan, it’s instantly more pressure,” the 36-year-old Sambath said. “It hangs over us every day.”

Cambodia, which has so far withstood the worst of the pandemic’s health effects, is at risk of financial meltdown due to millions of smallish loans like Sambath’s, which are ballooning into insurmountable debt as schools, factories and businesses remain closed.

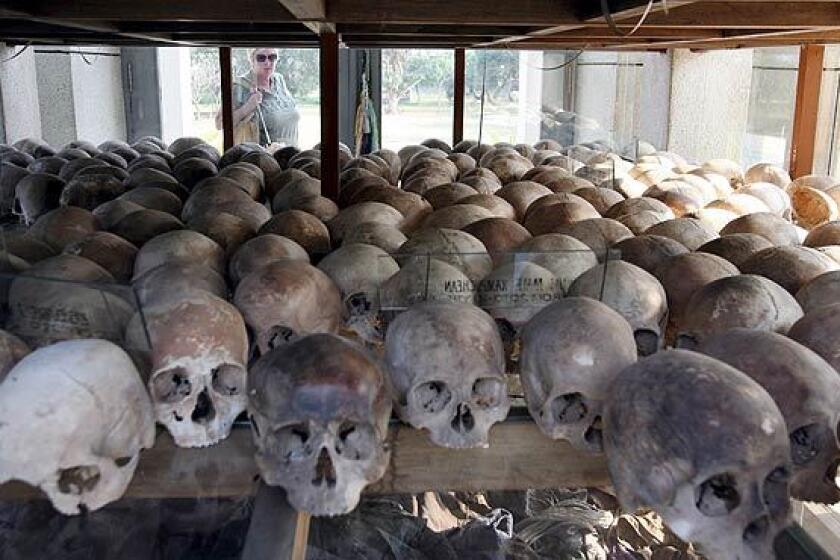

Cambodians are entangled in a microfinance system that was intended to alleviate poverty after decades of war, genocide and political turmoil; providing small loans to people without adequate access to formal banking services. But unlike other countries where microfinance lending is run by charities or subsidized by the government, Cambodia’s sprawling system is for-profit and privately run, charging interest rates as high as 18% and — with virtually no cap on how much a borrower can take out — many loans that aren’t “micro” at all, reaching into the tens of thousands of dollars.

Advocacy groups warn that predatory practices — including reports of intense pressure from lenders and coerced sales of homes and property — threaten to unleash a human rights crisis in a country where a $4,000 loan represents more than double the average annual income.

Borrowers were struggling even before the pandemic. And while the Southeast Asian nation has recorded fewer than 250 infections and no deaths due to the virus, the economic shutdown has erased hundreds of thousands of jobs in construction, tourism and export manufacturing, which includes the crucial garment and footwear sectors.

With the shutdown expected to last several more months, the World Bank estimates that at least 1.76 million jobs could be lost in a country of 15 million and that the poverty rate could rise from 13% to 24%.

The drop in foreign orders is devastating workers in the Southeast Asian country, which counts on the garment industry for 40% of its economic output. Those still employed now fear contracting COVID-19 inside cramped factories.

Three local advocacy groups said in a recent report that at the end of 2019, at least 2.6 million Cambodians owed more than $10 billion to domestic microfinance institutions. Many unemployed borrowers have stayed afloat by selling their homes or taking on more debt from usurious informal lenders.

In 2001, the average Cambodian microloan was $81, but the report found that the average has skyrocketed to $3,804 — more than twice the average annual income, and the highest level of microfinance debt in the world. Two-thirds of those surveyed had taken out at least one such loan.

The unpaid debt looms over Cambodians who face the prospect of many more months without salaries, health insurance or unemployment benefits, said Khun Tharo, program manager for the Center for Alliance of Labor and Human Rights, which co-wrote the report.

“It was easy to fall into poverty even before COVID — now the situation is much worse,” he said. “We’re seeing workers sleeping outside of factories. Many have no choice but to sell their homes or take on even more loans from informal lenders just to get by, not [to] mention any health or family emergency.”

Industry groups have objected to the report’s findings. The Cambodia Microfinance Assn., which represents more than 100 lenders, called the report biased, and the country’s biggest commercial bank, Acleda, accused the groups of defamation.

But the $10-billion figure might actually be an underestimate. Kaing Tongngy, a spokesman for the microfinance association, said that amount represents loans held by registered microfinance institutions and two major banks — not those provided by Cambodia’s roughly three dozen other banks or shadowy informal lenders.

Tongngy said that licensed microfinance institutions had restructured $1.3 billion in loans for nearly a quarter of a million borrowers as of mid-July. The association’s members do not seize land from insolvent borrowers, he said, calling the practice illegal and immoral.

What worries Tongngy are the informal lenders who charge monthly interest rates ranging from 10% to 50%. The loans don’t require income statements or credit checks, but come with no protections. Cambodian social media are rife with accounts of unscrupulous lenders putting pressure on families to sell property to repay loans.

“It’s a system that’s been here forever because in the past we had no access to formal lending,” he said. “Even now, the formal sector only reaches 80% of Cambodia.”

Disagreement between Cambodian and foreign judges appears to spell the end of a tribunal many hoped would be a landmark for international justice.

The pandemic has plunged more Cambodians, even those with access to banks, into a downward spiral of debt.

Sin Sotheary, a 39-year-old mother of two, used her family’s home as collateral to borrow $20,000 from a bank in December in order to buy a car and expand her clothing business. But her sales have dropped at least 80% and she hasn’t been able to make her $400 monthly payment.

“I’m scared, but doing my best,” she said. “My parents have to feed my children these days.”

A survey released last week by the Angkor Research consultancy and Future Forum, an independent think tank, found that nearly 25% of Cambodian families took out loans to pay off other loans in April, compared with 7.8% in January. The proportion of households that borrowed from informal lenders surged from 8.6% to 18%.

More stories from Asia

“We’ve never seen patterns of borrowing like this, with so many people taking on loans to pay other loans and buy food,” said Ian Ramage, director of Angkor Research, who added that in the past most people borrowed to start a business, build a house or throw a wedding.

“Cambodia has been on a good run and has some economic resilience,” Ramage said. “But if this trend continues, Cambodia is at risk of reversing 20 years of development and going back to being a country with a 40% poverty rate.”

Cambodia’s political leaders have shown little sympathy. After opposition leader Sam Rainsy, in self-exile in France, called on Cambodians to refuse to pay their debts to the banks, Prime Minister Hun Sen, the autocratic leader of 35 years, urged banks to seize the property of those who fail to pay.

In another speech, Hun Sen suggested that Cambodians who lost their jobs should return to farming in the provinces.

The government has promised subsidies to laid-off workers, and the central bank has encouraged all lenders to restructure loans until the pandemic passes. Jobless workers in the garment sector — the largest export industry, with $9 billion in revenues last year and some 750,000 employees — are eligible for a $70 monthly payment.

But many say they have not received any assistance. In July, thousands took to the streets of Phnom Penh, the capital, to demand salaries and benefits promised by factory owners who had closed their doors on short notice. Industry groups say that at least 400 factories have closed down, leaving more than 150,000 employees out of work.

Among those who haven’t received the payments is Sambath, who lives with her partner in a one-room apartment in a gritty industrial section of Phnom Penh. They worked in the same Chinese-owned factory until it closed. Now the couple worry about their parents and adopted son living in the provinces, who rely on them for money.

Sambath is running out of options. She has searched for cleaning, construction and security jobs, but no one is hiring. Days ago, she sold her $1,000 motorbike to the pawnshop where she had left it as collateral for a loan. The shop owner had threatened to seize the bike because she was so far behind on interest payments — so she accepted the only deal she could get.

She walked away with $20 and spent it on food.

“The only way out of this is to get a new job, whatever job I can find,” she said. “We can’t go on living like this.”

McDermid and Kea Pav are special correspondents.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.