Will the last of the Khmer Rouge ever face justice in Cambodian mass killings?

KAMPONG CHAM, Cambodia — He looks out from the picture, a slight man in a loose shirt, a pen in his pocket, the jungle stretching behind him. The photograph was taken after murders he was accused of committing when the Khmer Rouge swept through this nation decades ago in a reign of fevered killing and mass graves.

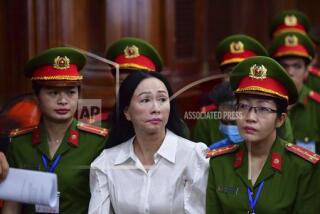

No one knows whether the man, Ao An, a former Buddhist monk now in his 80s, will ever face a reckoning on charges that he oversaw the genocide of the Cham ethnic minority during the 1970s. After nearly two decades, $300 million spent and only three convictions, a special United Nations-backed court established to try leaders of the murderous Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia appears to have ground to a halt.

The three remaining cases are stuck in limbo due to opposition from Cambodian court officials and the country’s authoritarian prime minister, Hun Sen, a former Khmer Rouge commander. The Cambodian officials on the hybrid tribunal — which includes judges and lawyers from both Cambodia and overseas — have stonewalled Ao An’s case.

In 2018, an international investigating judge ruled that the case against Ao An should proceed, while his Cambodian counterpart said it should be dismissed. Both sides appealed, landing the case in the pretrial chamber, where in December the five judges split: three Cambodian judges ruled for dismissal and two international judges said Ao An should be tried.

It was the first time there had been such an impasse, leaving the fate of that case and others in doubt, and rousing long-ago memories of pain, loss and bloodshed.

“There is no rule or mechanism to clarify what happens next,” Ao An’s defense team said in a statement.

John Ciorciari, director of the International Policy Center at the University of Michigan and a longtime tribunal observer, said it was “highly unlikely” that any remaining cases would go to trial. He blamed the breakdown on political pressure.

“When the prime minister publicly opposes [the remaining cases] and national officials fall uniformly into line, it is hard to reach any other conclusion,” Ciorciari said.

The tribunal was hailed as a step forward for domestic and international justice when it was established in 2003, after lengthy negotiations between Cambodia and the U.N., to try Khmer Rouge leaders. The ultra-Maoist organization took control of Cambodia in 1975, abolished money and religion, forced the population into rural communes and ruled by extreme force.

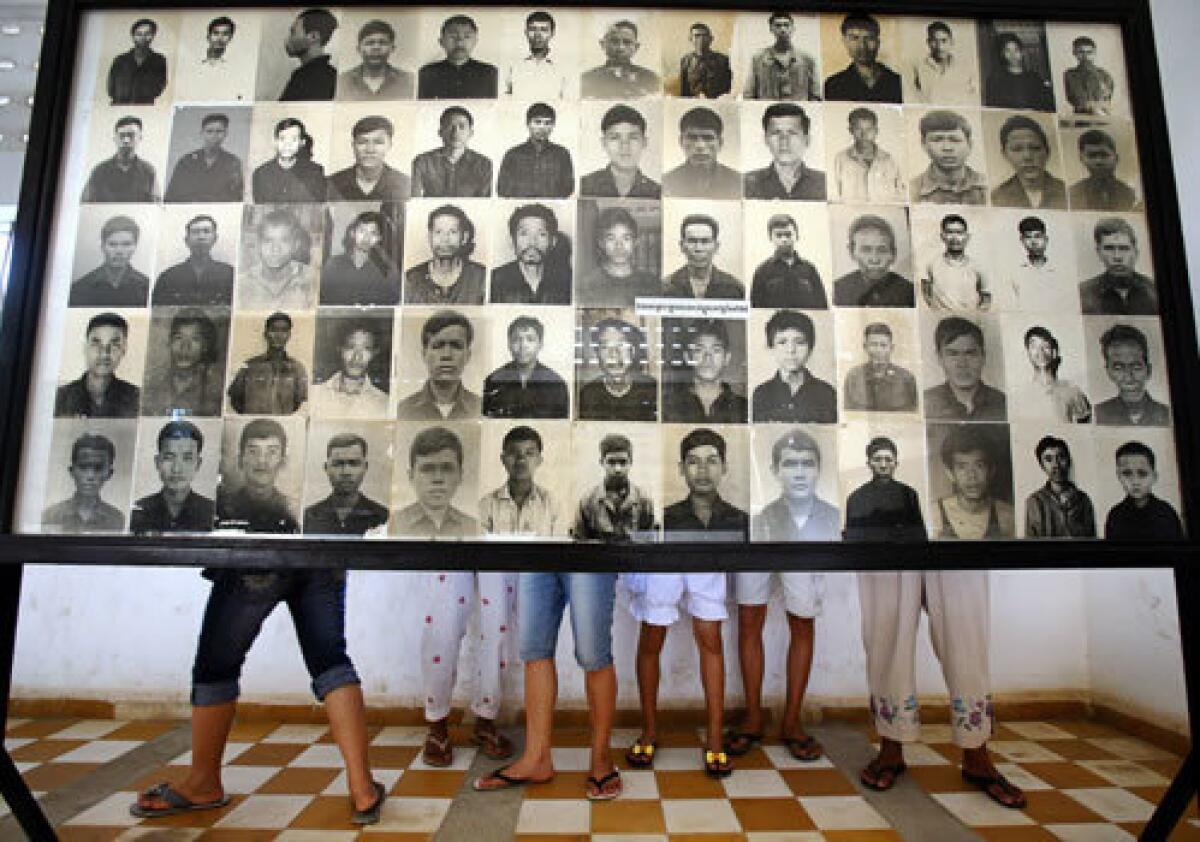

An estimated 2 million people died in less than four years from mass executions and starvation.

The Khmer Rouge fell in January 1979, overthrown by the Vietnamese army with assistance from defectors like Hun Sen.

Under the 2003 agreement with the U.N., Cambodia maintained significant control over the court, officially known as the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, which combines international and Cambodian laws. The court’s mandate was to try only senior leaders and those most responsible for atrocities, including allegations of genocide of ethnic Vietnamese and Muslim Cham minorities.

The head of the Khmer Rouge, French-educated Pol Pot, never faced a formal trial. His former followers placed him under house arrest in Along Veng, the regime’s last stronghold, in 1997. Once powerful enough to bend an entire nation to his will, Pol Pot’s body was burned on a pile of trash when he died of heart failure a year later.

The court convicted three of Pol Pot’s most notorious subordinates — Nuon Chea, Khieu Samphan and Kaing Guek Eav, also known as Duch. All were sentenced to life in prison for crimes against humanity, while Chea and Samphan were also found guilty of genocide. Chea died in August 2019.

One defendant was found unfit to stand trial in 2011 due to her deteriorating mental condition, and another died while on trial in 2013. Charges against one former Khmer Rouge official were dismissed.

While many Cambodians and international experts hoped the court would deliver justice, there was trepidation that Hun Sen might interfere. In power for 35 years, Hun Sen is one of the world’s longest serving leaders and has turned Cambodia into a de facto one-party state, banning opposition leaders and stifling the independent press.

Hun Sen has long opposed trials for Ao An and the two remaining defendants — Yim Tith and naval officer Meas Muth, who allegedly oversaw the executions of American sailors — warning they could lead to civil war. Investigating judges have issued conflicting orders in the two other cases as well.

Ao An, now living on a farm in rural Battambang, has long claimed his innocence.

Many current leaders in the Cambodian government were members of the Khmer Rouge, including Hun Sen and Heng Samrin, president of the lower house of parliament. Both operated in a region where Ao An was also allegedly active.

The Cambodian government has insisted no further investigations will be launched, but high-ranking officials could be implicated in witness testimony. Multiple attempts to call Heng Samrin to testify in previous trials were blocked by Cambodian court officials.

Further trials could “build momentum to a wider array of cases, eventually reaching people the government is resolved to protect,” Ciorciari said.

At the core of the deadlock in the court is that the co-investigating judges are meant to function as one office and were not supposed to issue conflicting orders. After the pretrial chamber split 3-2 in December, both the defense and prosecution claimed victory.

The international prosecutor, Brenda J. Hollis, claimed the case should proceed to trial because the judges hadn’t overturned the indictment. But Ao An’s lawyers said the case couldn’t proceed since a majority of judges ruled that he was not a senior leader, nor among those most responsible for Khmer Rouge crimes.

“There is no criminal justice system based on the rule of law which can continue with a case when a clear majority of judges have ruled in favor of dismissal,” said Göran Sluiter, a member of Ao An’s defense team.

“If one would nevertheless continue and take this to trial it will bring a permanent stain on the [court] and the system of international criminal justice in general.”

More than two months after the split decision, Sluiter said it was still uncertain whether the case would go forward.

Some aging former Khmer Rouge cadres believe Ao An should be spared, no matter how heinous the crimes under his watch.

So Saren, a 60-year-old former bodyguard for a high-ranking official who served under Ao An, recalled seeing two people executed at a Buddhist temple, their throats slit and stomachs cut open, in the district of Prey Chhor, part of what the Khmer Rouge called the Central Zone, where Ao An was second in command.

Ao An shouldn’t be tried, So Saren said, because he “got the order from the top level. If he did not follow [it], he would have been killed.”

Many experts believe dismissing the remaining cases would tarnish the court. Ciorciari said political interference and the court’s narrow scope “undermine its potential legacy as a model for an independent judicial process.”

But he credited the court for handing down “credible verdicts for some of modern history’s most heinous crimes. That important aspect of its legacy will remain.”

Survivors of Khmer Rouge massacres lamented the possibility that Ao An could escape trial.

Not far from the temple in Prey Chhor lies a rice field pockmarked with the remnants of mass graves. The graves were dug up after the Khmer Rouge fell, the bones placed in a long, open white tomb that serves as a memorial.

“If the law allows a trial it would be a good thing because he was a commander and is responsible for the bloodshed,” Ly Sary, a 55-year-old Cham Muslim who lives near the killing field, said of Ao An. “His hands are bloodstained.”

Nachemson is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.