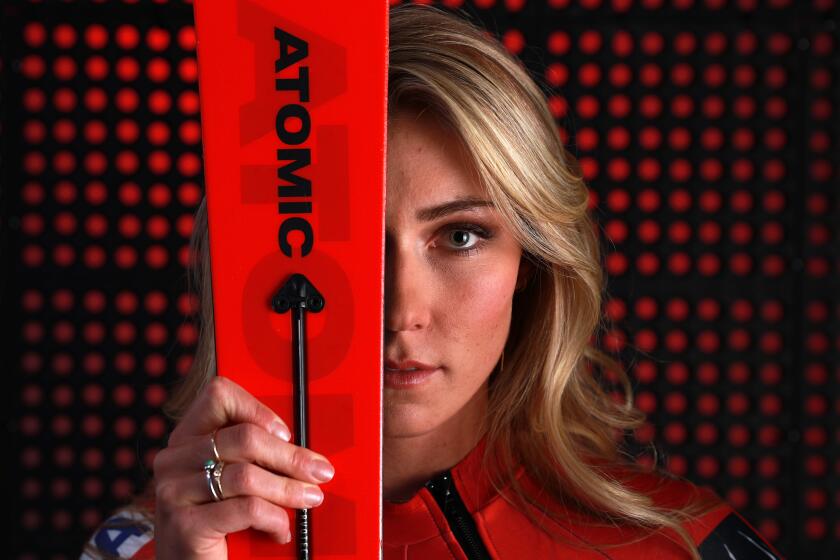

There was a time when Mikaela Shiffrin felt uneasy about athletes speaking out on social issues.

“I was of the mindset we should be more quiet,” she says. “Not just women. Everybody. Pipe down a little.”

Maybe she was projecting her natural shyness on others, but this attitude has evolved as Shiffrin enters her mid-20s and cements her place among the greatest ski racers — male or female — in history. In the last few years she has become more vocal about equal pay for women athletes.

“I guess I’m developing as a person,” she says. “I’m starting to have more opinions.”

If the 24-year-old Colorado native is testing the waters as an activist, she is approaching the role from an unusual angle.

Three Olympic medals and seven world championships have brought her a slew of endorsement deals with the likes of Adidas, Visa and Longines, reportedly paying millions each year.

Lilly King has been called brash, feisty and outspoken. But the reigning Olympic gold medalist in the 100-meter breaststroke sees it differently.

In addition, racing offers guaranteed equal minimum prize money for men and women. Because Shiffrin competes in a range of formats — from downhill to slalom — she has finished the past three seasons as the leading money earner on the international circuit.

Last year, that meant taking home about $900,000, well ahead of the now-retired Marcel Hirscher, who was No. 2 on the list. She says: “I’m proud to be part of a sport that has no gender pay gap.”

But female athletes in other sports aren’t as fortunate.

The U.S. women’s soccer team has filed a lawsuit demanding equal pay and treatment from their national federation. The women’s hockey team threatened to boycott the 2017 world championships, ultimately earning concessions from USA Hockey.

“A young girl watching her favorite male soccer player may think that’s great but there’s not a place for me in that scenario,” Shiffrin says. “We have to show young girls there is a future in women’s sport.”

Experts see this issue as key to the fight for equality in a traditionally male-dominated arena.

“The mentality for a long time has been that college sports are the end of the road for women,” said Cheryl Cooky, an associate professor at Purdue. “It would expand the competitive pool if girls and young women could see a viable career path.”

‘If your dream only includes you, it’s too small a dream,’ Clark says . ‘So I really embraced the idea of becoming a mentor.’

It took Shiffrin a while to ponder such matters, in part because of her early success. Bursting on the scene in 2011, she reached the podium and was named World Cup rookie of the year at 16.

“I started to make money,” she says. “It’s one of those things where ignorance is bliss.”

Her career since then has been a succession of superlatives. Youngest to win a slalom gold at the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. Youngest to reach 50 World Cup victories. First to win in all six World Cup disciplines. Seventeen World Cup victories set another mark last season and set the pace for a slew of wins this winter.

Through much of this record-breaking career, her attitude was don’t ask me anything controversial because I don’t want to say anything controversial.

Not that Shiffrin has all the answers now, but she wants to be part of the conversation. Seeing other female athletes speak out has helped her change. So has a modicum of age and maturity.

“Lately, as I’m watching these women stand up, it has been inspiring,” she says. “If you have a voice and people want to listen, it’s important.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.