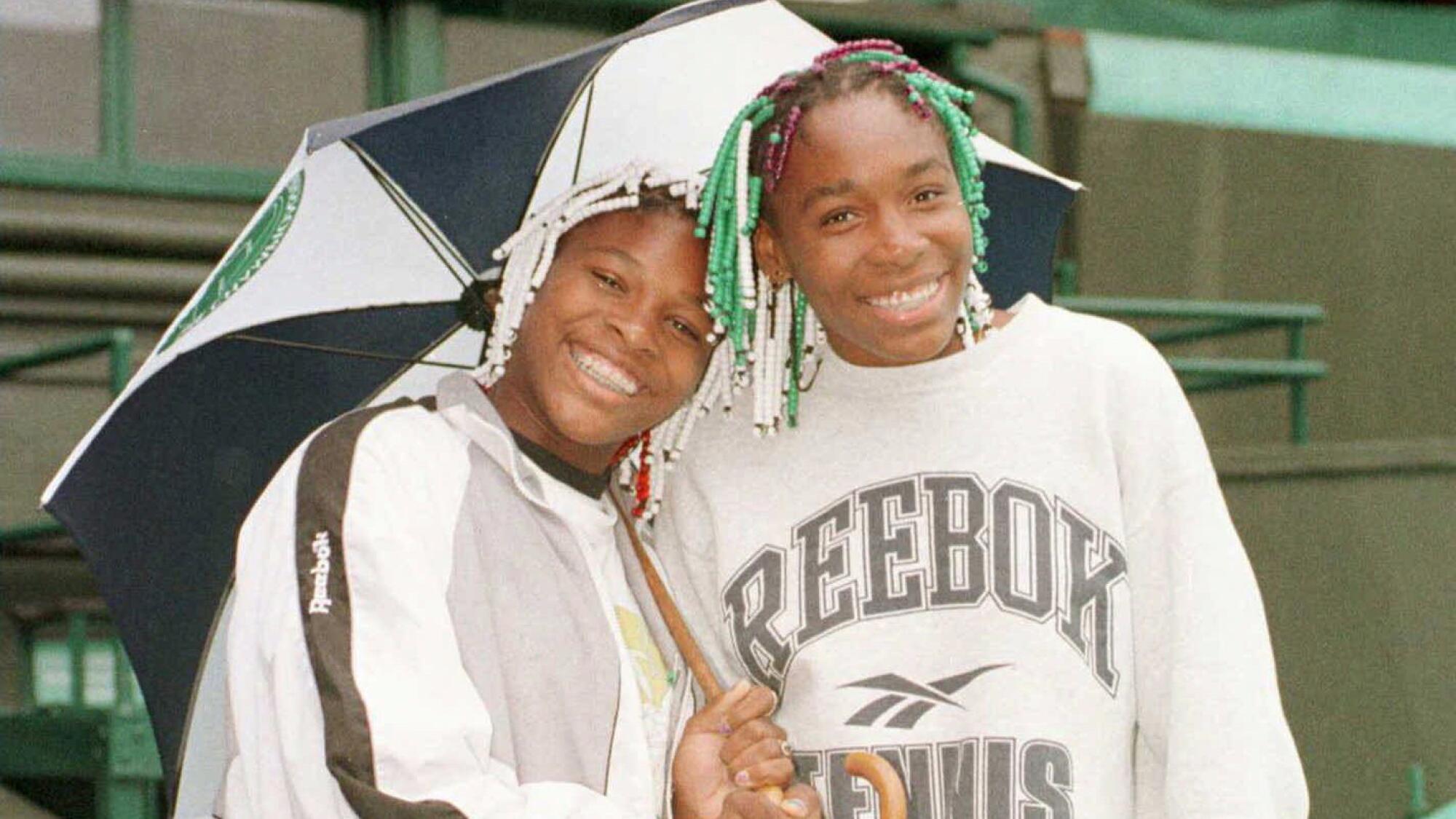

Serena Williams grew up in Compton, where she and her older sister Venus learned to play tennis on gritty public courts under the strict watch of their father, Richard. But both sisters now belong to the world, so dramatically have they changed their sport while making it better and more inclusive.

Serena has won more titles than her sister has, though she unfailingly credits Venus with leading the way along the unlikely path that two quiet but eager youngsters to become majestic Grand Slam champions.

They automatically defied the norm by being black in a largely white sport. Serena also flouted the norm with a muscular physique that puts thunder into her serve. She has used her power and presence to win 23 Grand Slam singles titles, one short of matching Margaret Court’s record. She won her last major at the 2017 Australian Open while she was in the early weeks of pregnancy with her daughter, Alexis Olympia Ohanian Jr.

Williams has attained that rare level of fame where she’s known by her first name alone. It’s whispered by worshipful young women who took up the sport because they saw a successful athlete who looked like them, and voiced respectfully by casual fans and rivals. “What she does and what she achieved, it’s something unbelievable,” Ukraine’s Elina Svitolina said after Williams routed her 6-3, 6-1 in a semifinal of the 2019 U.S. Open.

Because her career winnings exceed $92.7 million (more than double those of the runner-up, her sister Venus) and she fights for equitable pay for female tennis players, Williams has transcended the confines of the court, a truth she firmly rejects.

“I would be pontificating to a level I wouldn’t even know to say I’m a superstar,” she said during the 2019 U.S. Open. “Obviously, I’m just Serena. I don’t try to be anybody else. I don’t try to be famous. I don’t try to be anything.”

Nearly 50 years after Congress passed Title IX, female athletes are still scrambling for a fair shot in the male-dominated world of sport. In hockey, top Americans and Canadians train with their national teams part-time; the rest of the season, they have only a small pro league that offers twice-a-week practices, weekend games and thin salaries.

She has long been a role model for women of color such as Naomi Osaka, Sloane Stephens, Madison Keys and phenom Coco Gauff, but Williams takes no credit for inspiring them. “I can’t be presumptuous and say that’s because of me. I think it’s because of these young women, and their parents and coaches want them to do something amazing,” Williams says. “I think tennis is a great sport for females and it’s a great way to showcase your personality, be yourself, make a great living and still do something that you absolutely love.”

Williams was ranked No. 1 in the world when she took a maternity break in 2017. Olympia Ohanian was born Sept. 1 by Cesarean section, and Williams’ health was endangered when she developed blood clots. She needed several surgeries and was bed-ridden for six weeks. Tennis became secondary to recovery.

When she returned to competition at the 2018 BNP Paribas Open, she was ranked No. 549. She also wasn’t seeded at the French Open. In part because of the attention she brought to the issue, the Women’s Tennis Assn. decided to give protection to the rankings of women who return to the tour after giving birth or have been absent because of injury, allowing them to use their previous ranking to enter 12 tournaments over a three-year period after their comeback.

Williams, 38, has reached four Grand Slam finals since her return — at Wimbledon and the U.S. Open the last two years — but didn’t win a set in any of those matches. She lost in the third round at this year’s Australian Open and has acknowledged she’s still balancing the demands of her tennis career with the primal emotions of motherhood.

“You know, it’s hard. Sometimes my heart literally aches when I’m not around her,” she said of her daughter during last year’s U.S. Open. “But you know, it’s good for me, I guess, to keep working. And just to all the moms out there, it’s not easy. It’s really kind of painful sometimes. Sometimes you just have to do what you have to do.”

Williams’ legacy as a cultural icon and the greatest female player tennis has ever known is secure even if she doesn’t capture that record-tying 24th Grand Slam singles title. But don’t underestimate the fire that still drives her and fuels her confidence about winning another Slam singles title. “I definitely do believe or I wouldn’t be on tour,” she said after her loss in Australia in January. “I don’t play just to have fun. To lose is really not fun, to play to lose, personally.”

She never has played to lose, and never will.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.