The ‘science of reading’ swept reforms into classrooms nationwide. What about math?

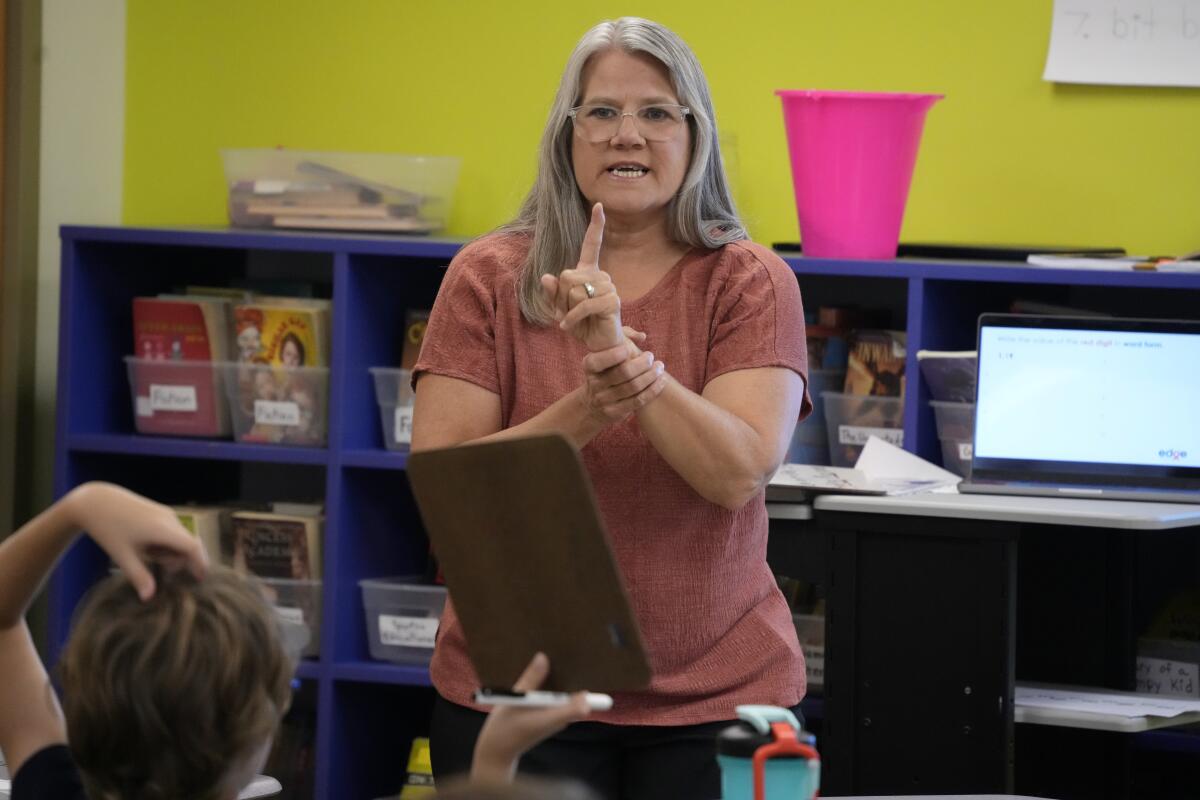

For much of her teaching career, Carrie Stark relied on math games to engage her students, assuming they would pick up concepts like multiplication by seeing them in action. The kids had fun, but the lessons never stuck.

A few years ago she shifted her approach, turning to more direct explanation after finding a website on a set of evidence-based practices known as the science of math.

“I could see how the game related to multiplication, but the kids weren’t making those connections,” said Stark, a math teacher in the suburbs of Kansas City. “You have to explicitly teach the content.”

As American schools work to turn around math scores that plunged during the pandemic, some researchers are pushing for more attention to a set of research-based practices for teaching math. The movement has passionate backers, but is still in its infancy, especially compared with the phonics-based “science of reading” that has inspired changes in how classrooms across the country approach literacy.

Experts say math research hasn’t gotten as much funding or attention, especially beyond the elementary level. But the math instruction schools are currently using doesn’t work all that well. The U.S. trails other high-income countries in math performance, and lately more students graduate high school with deficits in basic math skills.

Advocates say teaching practices supported by quantitative research could help, but they are still coming into focus.

“I don’t think the movement has caught on yet. I think it’s an idea,” said Matthew Burns, a professor of special education at the University of Missouri who was among researchers who helped create a Science of Math website as a resource for teachers.

Supporters say proposed state K-12 framework will make higher-level math accessible to more. Critics contend it will make poor math outcomes worse.

There’s a debate over which evidence-based practices belong under the banner of the science of math, but researchers agree on some core ideas.

The foremost principle: Math instruction must be systematic and explicit. Teachers need to give clear and precise instructions and introduce new concepts in small chunks while building on older concepts. Such approaches have been endorsed by dozens of studies highlighted by the Institute of Education Sciences, an arm of the U.S. Education Department that evaluates teaching practices.

That guidance contrasts with exploratory or inquiry-based models of education, where students explore and discover concepts on their own, with the teacher nudging them along. It’s unclear which approaches are used most widely in schools.

Just thinking about math can make your head hurt, study confirms

In some ways, the best practices for math parallel the science of reading, which emphasizes detailed, explicit instruction in phonics, instead of letting kids guess how to read a word based on pictures or context clues. After the science of reading gained prominence, 18 states in just three years have passed legislation mandating that classroom teachers use evidence-backed methods to teach reading.

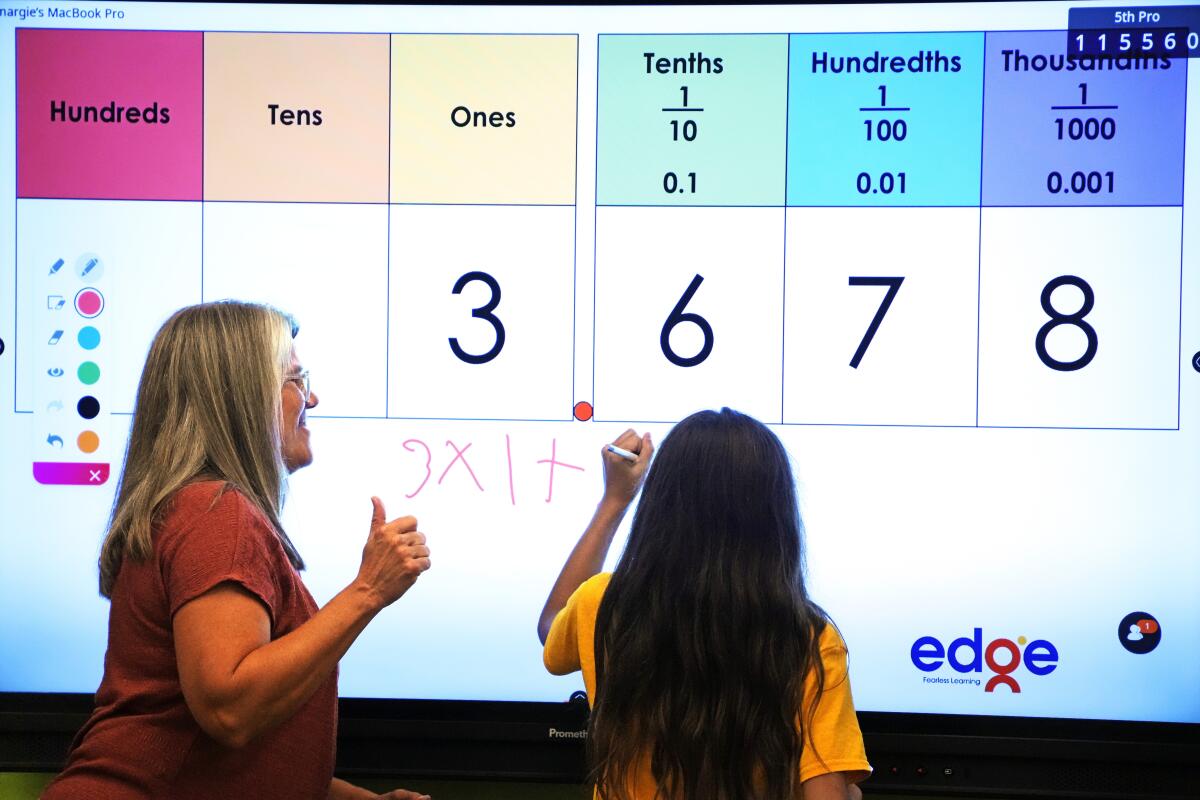

Margie Howells, an elementary math teacher in Wheeling, W.Va., first went researching best practices because there weren’t as many resources for dyscalculia, a math learning disability, as there were for dyslexia. After reading about the science of math movement, she became more explicit about things that she assumed students understood, like how the horizontal line in a fraction means the same thing as a division sign.

“I’m doing a lot more instruction in vocabulary and symbol explanations so that the students have that built-in understanding,” said Howells, who is working on developing a science-based tutoring program for students with dyscalculia and other learning differences.

Some elements of math instruction emphasize big-picture concepts. Others involve learning how to do calculations. Over the decades, clashes between schools of thought favoring one or another have been labeled the “math wars.”

A key principle of the science of math movement is that both are important, and teachers need to foster procedural as well as conceptual understanding.

“We need to be doing all those simultaneously,” Stark said.

When Stark demonstrates a long division problem, she writes out the steps for calculating the answer while students use a chart or blocks to understand the problem conceptually.

Stark helps coach fellow teachers at her school to support struggling students — something she used to feel unequipped to do, despite 20 years of teaching experience. Most of the resources she found online just suggested different math games. So she did research and signed up for special trainings, and started focusing more on fundamentals.

For one fifth-grader who was struggling with fractions, she explicitly re-taught equivalent fractions from third grade — why two-fourths are the same as one-half, for instance. He had been working with her for three years, but this was the first time she heard him say, “I totally get it now!”

“He was really feeling success. He was super proud of himself,” Stark said.

Our brains are not hard-wired for math, but mathematical concepts are often taught as if they are self-evident.

Still, skeptics of the science of math question the emphasis placed on learning algorithms, the step-by-step procedures for calculation. Proponents say they are necessary along with memorization of math facts (basic operations like 3x5 or 7+9) and regular timed practice — approaches often associated with mind-numbing drills and worksheets.

Math is “a creative, artistic, playful, reasoning-rich activity. And it’s very different than algorithms,” said Nick Wasserman, a professor of math education at Teachers College at Columbia University.

Supporters argue mastering math facts unlocks creative problem-solving by freeing up working memory — and that inquiry, creativity and collaboration are still all crucial to student success.

“When we have this dichotomy, it creates an unnecessary divide and it creates a dangerous divide,” said Elizabeth Hughes, a professor of special education at Penn State and a leader in the science of math movement. People feel the need to choose sides between “Team Algorithms” and “Team Exploratory,” but “we really need both.”

Best practices are one thing. But some disagree such a thing as a “science of math” exists in the way it does for reading. There just isn’t the same volume of research, said education researcher Tom Loveless.

“Reading is a topic where we have a much larger amount of good, solid, causal research that can link instruction to student achievement,” he said.

Female teachers may pass on math anxiety to girls, study finds

To some, the less advanced state of research on math reflects societal values, and how many teachers themselves feel more invested in reading. Many elementary school teachers doubt their own math ability and struggle with anxiety around teaching it.

“Many of us will readily admit that we weren’t good at math,” said Daniel Ansari, a professor of cognitive neuroscience at Western University in Canada. “If I was illiterate, I wouldn’t tell a soul.”

Still, Ansari said, there is enough research out there to make a difference in the classroom.

“We do understand some of the things that really work,” he said, “and we know some of the things that are not worth spending time on.”