Gavin Newsom describes struggling with dyslexia as he governs California through crisis

SACRAMENTO — California’s most powerful politician often begins his day around 6 a.m. alone in his office, struggling to read.

With his headphones on and the door closed, Gov. Gavin Newsom goes through his daily briefing binder once. Then a second time. Then a third.

His staff knows to give him space for at least two hours as he circles and underlines the reports. He distills pages of notes onto yellow cards and slides them into his pocket to study during the ride to news conferences or speaking engagements.

Newsom says the painstaking system helps him retain information and compensate for his dyslexia. It’s a bit of a security blanket for a governor who said he didn’t feel smart until age 35.

“The only way I’m going to be confident in my job and be able to do my job is I’ve got to be confident enough in what I’m trying to communicate and what I’m trying to say,” Newsom said. “Otherwise, I’ll be deeply anxious about my job, and I will not enjoy it. That’s like not getting sleep the night before. It’s not a day I want to experience.”

In front of the cameras, Newsom’s propensity for rattling off numbers and facts can feed into the public image of a self-assured and all-too-polished politician. But it’s also a byproduct of insecurities over learning issues that seeped into his consciousness at an early age.

“I’m in a sort of perpetual place of trying to overcompensate, trying to prove something to myself,” Newsom said.

Dyslexia affects 20% of the population and can be experienced differently from person to person, according to the Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity.

“It’s spelling, writing and just deep struggles reading — and the reading is comprehension, because I can read two chapters and literally be daydreaming, and I’ll have read every word and not remember one damn thing unless I’m underlining it,” Newsom said.

While growing up, Newsom said, other children viewed him as the “slow kid” and laughed at him. His sister, Hilary Newsom, said he was incredibly shy and sometimes bullied.

She remembers a lot of crying, arguments and frustration over homework between her brother, who is 14 months her senior, and their mother, who tried to help him.

“He couldn’t understand it, and you know, it just came so difficult,” she said of her brother’s learning issues. “It was just really emotional for both of them.”

Newsom learned about his dyslexia diagnosis by snooping through his mother’s papers when he was in fifth grade. She had kept it from him because she didn’t want him to be stigmatized or to give him an excuse not to work hard, he said.

In the 1970s, when Newsom entered school, more physicians and mental health experts had begun to recognize that the learning disorder was rooted in the ways children’s brains worked, but it was not widely understood, said Dr. Robert Hendren, co-director of the Dyslexia Center at UC San Francisco.

Hendren said the trauma and self-doubt people with dyslexia suffer during childhood never really goes away.

“There are people who are very smart, and they find ways to get around not being able to read,” Hendren said. “But there’s still that inner feeling of kind of faking out the world.”

In his 20s, Newsom said, his first business plan helped him recognize his visually creative side. Three or four businesses later, he started to appreciate his dyslexia.

“Then I became just fascinated by how many people that I admired ... had dyslexia in common, and so I started seeing it then as a strength,” Newsom said, citing as examples financier Charles Schwab and Richard Branson, founder of Virgin Group.

Newsom eventually launched a series of successful wine stores, wineries, bars, restaurants, event spaces, hotels and shops in the Bay Area, Napa Valley and Lake Tahoe.

But “it didn’t make me feel smarter,” he said. “It didn’t make me feel intellectually capable.”

As his businesses took off, so did his political career. He was appointed in 1996 to San Francisco’s Parking and Traffic Commission and the following year to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors.

Newsom said he didn’t begin to shake the feeling of being intellectually inferior until he ran for San Francisco mayor in 2003.

“This is an extraordinarily bright guy, the antithesis of me,” Newsom said of his opponent, Matt Gonzalez, who was president of the Board of Supervisors and a Green Party candidate.

On the debate stage, Newsom realized he could hold his own.

“I started developing a little more confidence, intellectual confidence, and the confidence just came from the grit and grind that is also the gift of dyslexia,” Newsom said. “I realized I’m just gonna outwork everybody. No one’s gonna outwork me, and I’m going to become an expert on the subject matter.”

Newsom became San Francisco’s youngest mayor in 2004, went on to serve as lieutenant governor and captured the governor’s office in 2018 with the largest margin of victory in more than a century.

But his sister said the road to power wasn’t paved as smoothly as it’s often described. Their parents’ divorce in 1971 set the stage for an unusual dual existence: They were largely raised by a young, single mother who at times worked three jobs, but Newsom also benefited from his father’s connections to the highest echelons of San Francisco’s Democratic establishment and the Gettys.

Their father, William Newsom, was a former state appellate court judge who managed the Getty family trust.

Hilary Newsom said their mother, Tessa, for a period slept in the dining room of their two-bedroom flat in San Francisco, giving the two kids a shared room and renting out the second to a woman and her three children, in order to bring in more income.

“She had our feet very firmly planted in reality,” she said of their mother, describing occasional interludes into their father’s world. “We came home to a really hardworking mom who grounded us and made us appreciate everything.”

In an interview about his new children’s book, “Ben & Emma’s Big Hit,” Newsom said he sees himself as the baseball-loving protagonist of his story, who is so embarrassed by his dyslexia that he sweats in class and runs out of the room overwhelmed by shame and frustration. He said he’s also Emma, Ben’s teammate who totes around books she can’t read as a way to cover up her reading issues, and he’s a reflection of his mother.

“I’m not the person that I see in those headlines, the Gavin-Getty articles that have been written 3,000 times,” Newsom said.

The support Newsom received from the Getty family to his businesses and campaigns has been well-chronicled throughout his career, and some of his friends and family believe it has had an outsize influence on the “silver spoon” narrative about his life.

“I just wish people really knew that just because you have this support doesn’t mean you don’t have to work really hard to make it successful,” Hilary Newsom said. “I think that was conditioned in him as a kid.”

Peter Ragone, a political consultant who served as press secretary while Newsom was mayor of San Francisco, said his preparation process is different from that of most politicians.

Newsom’s staff couldn’t just hand him a thick binder of briefing material. He would conduct exhaustive question-and-answer sessions with them in order to commit the information to memory.

“It was always a trump card for us, whether it was in meetings or in debates or public appearances,” Ragone said of Newsom’s preparation. “He just really did his work and understood the facts and the policies and the reasoning on a very deep level.”

Newsom described his level of preparation as “absurd.” His extensive files and notes, dating back to his time as a supervisor, filled more than an entire room when he moved offices earlier this month, he said.

“I have files and files,” Newsom said. “Everything is underlined, circled, and I put it on 8-by-10 white papers, and then there’s like thousands of these stacks ... every topic, subject matter. And then I take from that subject matter and break it down to two or three pages, and then I try to eventually get it on these yellow cards.”

Newsom said the yellow cards contain “the best of the best of” the points he has read on the topic. He often speaks at news conferences without a prepared speech by referring to his notecards and research.

“In the years I’ve been in politics, I’m just mesmerized by the politicians that are literally handed a script or talking points from an advisor at an annual event or you name it, and they’re able to go up there and just read off the script beautifully,” Newsom said. “Then I’m up there having done all this research, spending like six hours to give a five- or six-minute presentation.”

Speeches prove particularly daunting. He uses a teleprompter for major addresses, such as the State of the State, which requires him to memorize not only the speech but how the words look on the screen. Last-minute changes threaten to throw off his entire delivery, his aides say.

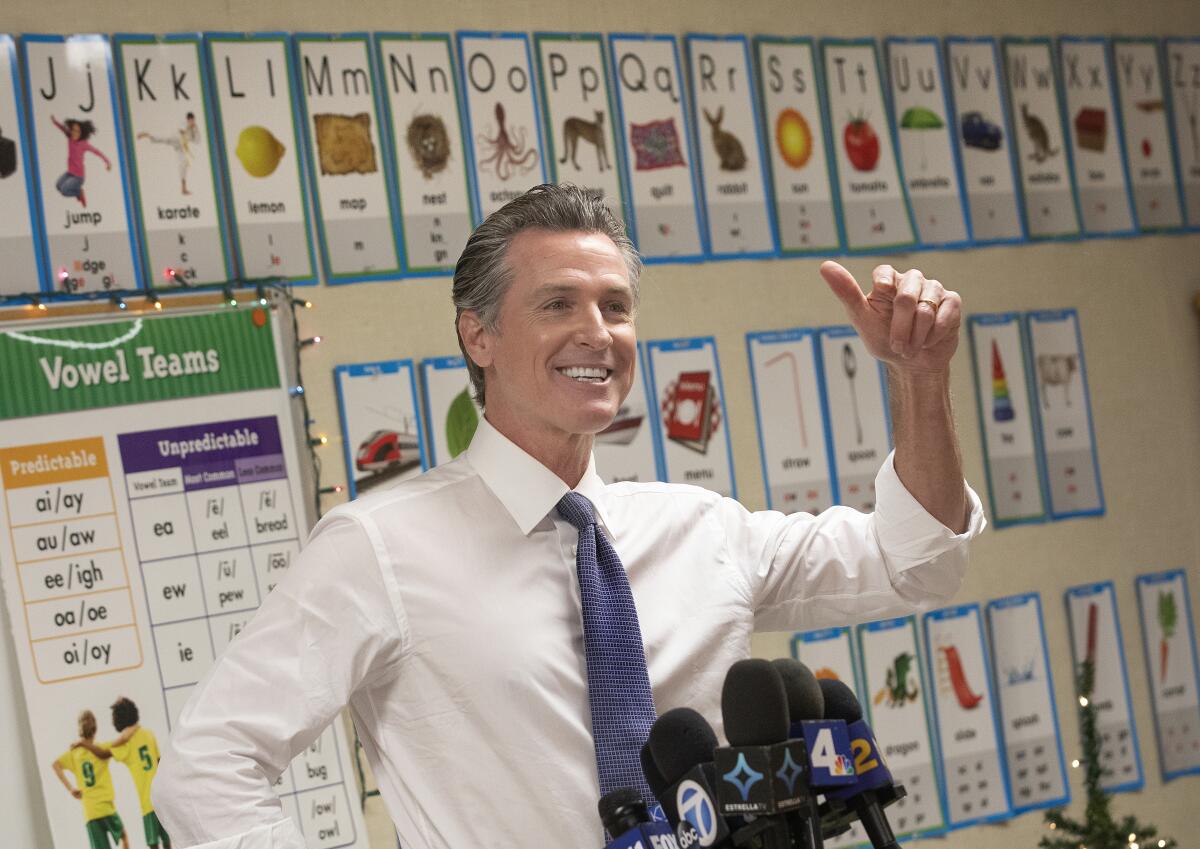

Newsom has been traveling up and down the state this month visiting classrooms to talk about his experiences growing up.

Last week, the governor sat perched on a stool in front of a class of kindergarteners at Arminta Elementary School in North Hollywood to share his story.

“It’s kind of a book that’s a little bit about me growing up,” Newsom told the students.

Now the 54-year-old governor often talks about what he sees as the silver lining of his struggles with dyslexia: his determination, work ethic, razor-sharp memory and the fact that he no longer feels afraid to fail.

Dyslexia, Newsom said, has also made him appreciate those who are different. It’s the reason for a line he repeats over and over: California doesn’t just tolerate diversity but celebrates it.

“It’s all inherent in the identity of who I am as someone that’s different,” he said. “I’m deeply emotional about people that are hurt, being bullied, struggling.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.