UC stirs furious debate over what high school math skills are needed to succeed in college

Briana Hampton, a San Gabriel High School junior, is determined to get into a four-year university to achieve her dream of becoming a social worker or psychiatrist. But she feared she would fail a third-year math course heavy on advanced algebra.

To meet her math requirement, she opted instead for an introductory data science course, approved a few years ago by the University of California as an alternative to advanced algebra. She loves the challenge of learning how to code, conduct surveys and analyze data on topics relevant to her life — sleep hours, stress levels, snacks consumed. She’s also boasting a B average in the class, compared to the Ds and Fs earned in her first-year math class.

“I’ve always struggled with math, but I heard that [data science] was like a really good class and something new and easier than algebra,” Briana said.

But the data science option is gone, at least for now. Last month UC notified California high schools that three of the most popular data science courses no longer count toward the advanced math requirement because the classes fail to teach the upper level algebra content all incoming students must know.

The decision has ratcheted up math anxiety and fomented confusion among high school students throughout California as they chart their high-stakes path for coveted UC admissions. California high schools offering data science classes — about 435 across the state — are also uncertain over how to revise curriculum and counsel their students.

UC first approved a data science course submitted in 2013 by Los Angeles Unified as a move to expand math options for students. At the time, the decision drew little notice. Over the years, efforts spread to increase data science in schools. After the subject was given a more prominent place in California’s new state framework for math instruction adopted last year, UC reviewed its years-old decision.

Faculty math experts concluded the course and two others were too weak on algebra and nixed them as an advanced math alternative. The decision also applies to the California State University system, which shares coursework admission requirements with UC.

The turnabout has unleashed furious debate over what high school math skills are needed to succeed in college — and how best to deliver them equitably to a diverse range of students. Currently, UC and CSU require for admission a three-year sequence of algebra, geometry and advanced algebra — or the equivalent integrated math courses. Both also recommend a fourth year of mathematics beyond those foundational skills.

Where data science fits in and what advanced math courses need to include to meet admission requirements is hotly contested. The UC Board of Regents will take up the issue at its meeting Wednesday and has the authority to overrule the faculty decision.

The debate

Opponents of UC’s reversal argue that data science courses give students essential skills to extract meaning from the modern world’s information deluge. They also offer an alternative path to college for those who may struggle with algebra and don’t plan to pursue calculus and STEM majors. About 44% of high school seniors fail to complete two semesters of advanced algebra, according to UC.

Denise Jaramillo, Alhambra Unified School District superintendent, said she was concerned by the UC decision because many of her students have taken the now-disallowed data science courses and have gone on to succeed in college. The district has used a course developed by UCLA since 2017.

University of California applications rose to 250,000 for fall, driven by a rebound in transfer applicants and gains in racial, ethnic and socioeconomic diversity.

“Limiting student options and choices has never been an equitable practice in schools or the classroom, and doing so has the potential of placing historically marginalized groups at a great disadvantage after high school,” Jaramillo said in a statement.

But supporters of the UC decision counter that all students should be equipped with advanced algebra skills and not tracked into set pathways at such young ages — especially Black, Latino, female and others who are underrepresented in the high-demand, high-paying fields of science, technology, engineering and math.

“Students from underrepresented groups are the most vulnerable to make misinformed pathway choices in high school that could lead them away from preparedness for quantitative majors,” said Jelani Nelson, a UC Berkeley professor of electrical engineering and computer sciences.

Nelson, who is Black, has been particularly outspoken in the debate because he said “misleading marketing” from some data science courses claim they prepare students for STEM coursework and data science majors. But, he said, hundreds of faculty members, along with Elon Musk and industry leaders from OpenAI, Apple, Microsoft, NVIDIA, Google Research and other firms, agree that advanced algebra is essential for those fields.

Jennifer Chayes, dean of UC Berkeley’s new College of Computing, Data Science and Society, said “thousands” of students change their minds about majors once they come to campus. Many intend to study such fields as environmental science, health or criminal justice — then discover an affinity and aptitude for data science and other STEM disciplines and need the math skills for them.

“People are pitting this as data science versus algebra, but that’s really not right,” Chayes said. “It’s data science using algebra 2 that we’re really going to want to do.”

Nelson added that efforts are underway to develop data science courses that include advanced algebra — including one by Bootstrap, an educational nonprofit — and he and other STEM professionals welcome such moves.

A new California legislative effort to ban state financial aid to colleges and universities that give admissions preferences to children of alumni and donors could hit USC, Stanford.

James Steintrager, chair of the UC Academic Senate, said the faculty organization is open to appropriate high school data science courses counting for admission in some way.

“There’s nothing wrong with data science, per se,” he said. “But if it’s not rigorous enough, you’re not preparing UC students, including diverse UC students, for the variety of careers, STEM careers in particular, that they could have. They’re not going to thrive. So you’re really doing those students a disservice.”

A letter to Board of Regents Chair Rich Leib signed by more than 230 school, district and county education leaders castigated UC for the flip-flop, saying they were shut out of the decision, yet have to manage the impact, including a “significantly” reduced ability to teach 21st century data and statistical skills. In another letter Monday to Leib, a University of Chicago data science advocate said the bitter California conflict has reverberated nationally.

The uncertainty over the future of data science courses may cause districts to pause or shut down programs — as San Diego Unified has done — cut resources for teacher professional development, and lead students to believe the field is different from math, said Zarek Drozda, executive director of Data Science 4 Everyone. His group concurred that the current data science courses don’t cover advanced algebra, but believed they can and should be allowed as a fourth-year math option.

Fewer than 400 of about 250,000 applicants to UC last year had taken data science or statistics instead of an algebra 2-type course. CSU data were not available. But as both public university systems collectively enroll the top one-third of California high school graduates, it is likely that the overwhelming majority of applicants take advanced algebra or its equivalent. About two-thirds of California high school students have taken algebra 2 by 11th grade, according to Michal Kurlaender, a UC Davis professor of education policy.

Hollywood High School, for instance, directs all students to complete the three-year math sequence ending in advanced algebra and take data science as a fourth year math option. Securing approval for data science and statistics courses to count for that fourth year of math recommended by UC and CSU is the lobbying focus by the Campaign for College Opportunity and other equity advocates.

But the ramifications of any UC action on the issue could be far-reaching even for students who don’t plan to apply to UC and CSU. Los Angeles Unified, for instance, requires all students to complete that college-prep coursework to graduate. In a districtwide memo issued last spring, L.A. Unified told schools that the data science course it had piloted could substitute for advanced algebra.

LAUSD initiated data science courses

In 2013, LAUSD became the first in California to seek and receive UC approval to offer a data science course.

L.A. schools Supt. Alberto Carvalho called the situation an “age-old dilemma in mathematics regarding the theory of mathematics versus the application.” The data science course includes “sufficient algebraic thinking and operations to satisfy the practicality of mathematics, but may, in fact, fall short of a true course in algebra that provides the A through Z of all algebraic concepts,” he said Tuesday.

School board member Nick Melvoin said the debate underscores the need for better early math instruction. Board members Jackie Goldberg and Tanya Ortiz Franklin support data science, but not at the expense of mathematical rigor.

The district has yet to provide information requested three weeks ago about how many schools currently offer the introductory data science course and how many students had taken it in lieu of advanced algebra.

Robert Gould, a UCLA teaching professor and undergraduate vice chair in the Department of Statistics and Data Science, led efforts to create coursework as part of a National Science Foundation-funded project to help students develop computational thinking and increase engagement in STEM studies. Initial four- to six-week programs that were developed using data in algebra and biology were too short for meaningful learning, Gould said.

But the move to establish new statewide learning standards, part of a national effort, offered an opportunity to create a year-long course because the new “common core” put more emphasis on statistics.

UC approved the data science course in the statistics category. The university listed statistics as an allowable substitute for algebra 2, according to a 2013 UC document.

Data science scrutinized

Gould said the 2020 release of the initial draft of the state guidance for math instruction, known as the California Math Framework, intensified scrutiny because of an emphasis on data science courses. He joined a UC committee that recommended data science courses should be allowed to count for third- and fourth-year math — and the UC faculty board overseeing admission approved the recommendation in October 2020. A year later, a faculty board statement on math included sample course sequences that showed data science and statistics following algebra and geometry instead of algebra 2.

But CSU faculty objected.

In March 2023, the CSU Academic Senate approved a resolution saying Gould’s course represented “inadequate preparation for college and career readiness” that could put 11th-graders at risk in state math testing and “in turn threatens to increase the number of students entering the CSU who are identified as needing extra support to succeed.”

Rick Ford, who headed a CSU faculty committee on academic preparation at the time, said concerns about racial and ethnic disparities in math were well-meaning but misplaced.

“A major issue that I share with many of my equity-minded mathematics education colleagues is that too often we are seeing folks wanting to change standards or curriculum to address the ethnic and racial differentials in success in foundational high school mathematics courses,” he said in an email. “Instead, we should be focusing our efforts on building the proper support necessary to improve those success rates.”

The issue came to a head in July 2023, as state education officials prepared to vote on the new math framework that included data science as an alternative pathway. Amid ferocious lobbying on all sides, the UC faculty board voted to reverse the earlier approval of data science courses.

A working group, appointed to delve into the issues, affirmed the turnabout last month and UC then notified high school counselors.

Gould said he disagrees with conclusions that his course fails to prepare students for college. Still, he said he would do “what it takes” to revise the course as needed to make sure students can continue to gain exposure to data and statistical skills. Today, 7,681 California students are taking his course in 89 schools, along with thousands more in other states and countries.

Inside a data science class

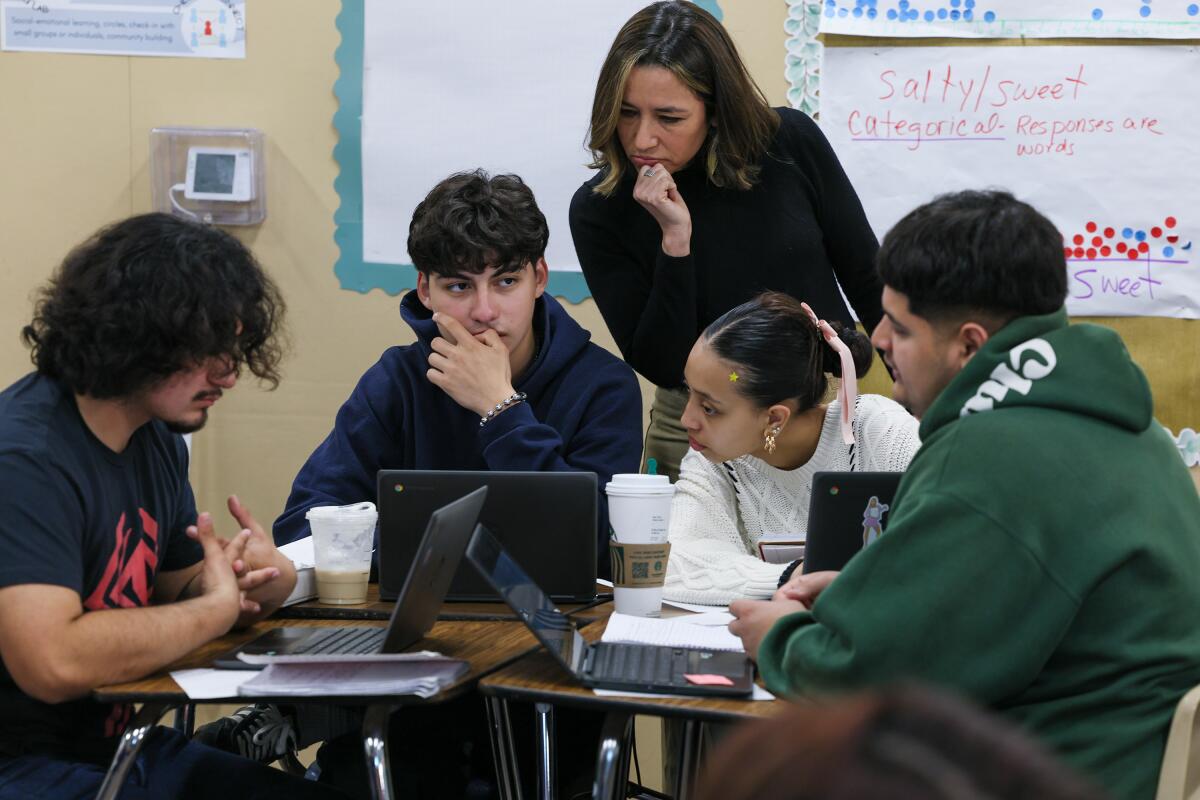

Nearly 100 of those students attend San Gabriel High — and judging by a recent visit, love the data science course.

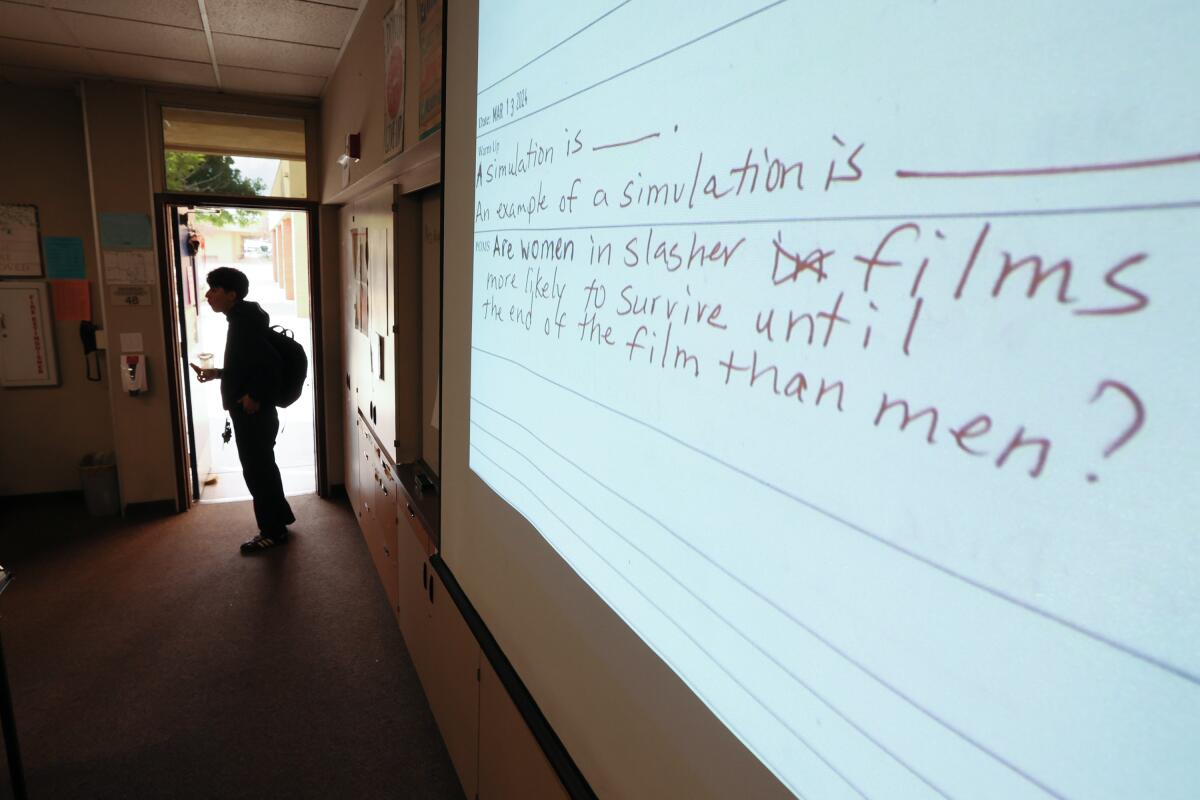

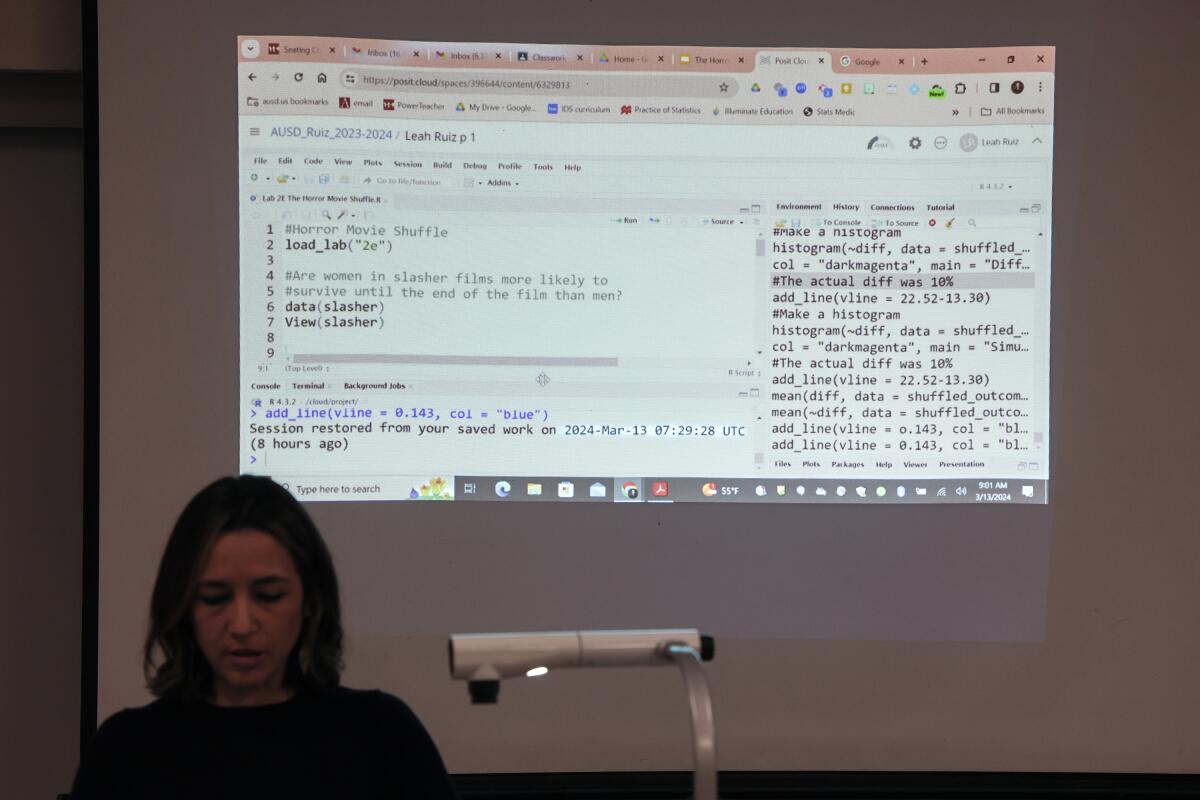

On this day, they are delving into data on whether females or males die more often in horror slasher films. Leah Ulloa Ruiz, the teacher, leads her class through data files of 485 characters in 50 films. She peppers them with questions and directs them to use coding to find answers.

Ruiz said many of her students say they hate math or don’t understand it. But data science lights them up, gives them confidence and teaches them the importance of data and statistical skills. The UC decision to not count data science as an advanced mathematics course for admission, she said, is wrong.

“I really think it’s a shame and a step backwards,” she said. “A student can be successful in life with a career, job and money without taking algebra 2 or integrated math 3.”

Two of her students, Noah Minchaca and Valentina He, both struggled with algebra-heavy integrated math courses. Valentina failed her second-year course and had to repeat it in the summer, while Noah managed to pass it but said he spent most of the time in class with his head on his desk, napping. He dropped out of his third-year course after two weeks.

“You can’t understand it,” Noah said of his integrated math course. “You keep seeing Ds on your tests and ask, ‘Am I dumb?’ Your self-esteem is blown. And it’s useless, just equations.”

“Yeah, polynomials — you can’t use it in the future,” Valentina said.

But the students said the data science course has taught them skills they expect to use in the future. Noah already has been accepted into an architecture program with Glendale Community College and San Diego State University, while Valentina is thinking about a trade school for training as a medical assistant.

Briana, meanwhile, won’t have to take the third-year integrated math course she skipped in favor of data science since the UC ruling won’t affect students until next year. That’s a relief since she’s planning to apply to both CSU and UC, although her first choice is a historically Black college. But she feels for students who follow her.

“That really sucks,” she said. “I know a lot of kids here are really bad at math and struggle with math. And they’re kind of being forced into a class that I’m not sure it’s gonna help them succeed.”

Staff writer Howard Blume contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.