Los Angeles Times

Jon Lomberg’s most far-flung work of art is currently more than 14.8 billion miles away, in the cold no-man’s land between the sun and its closest stars.

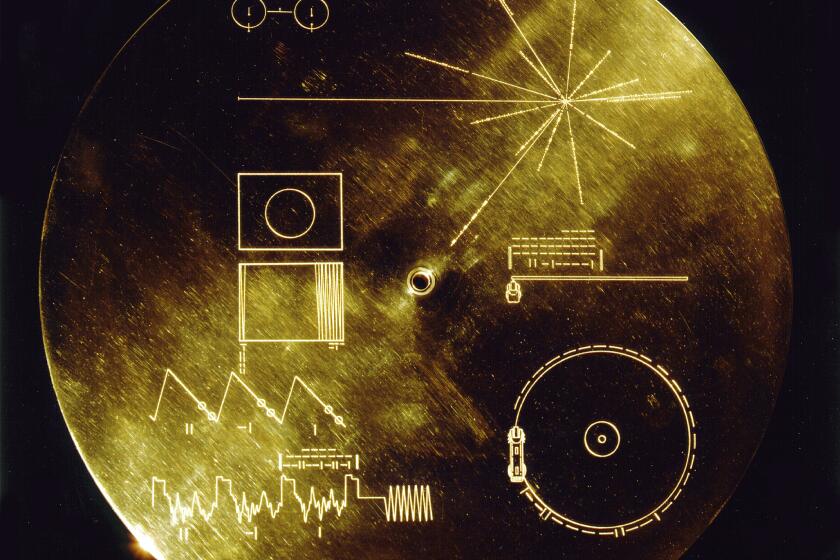

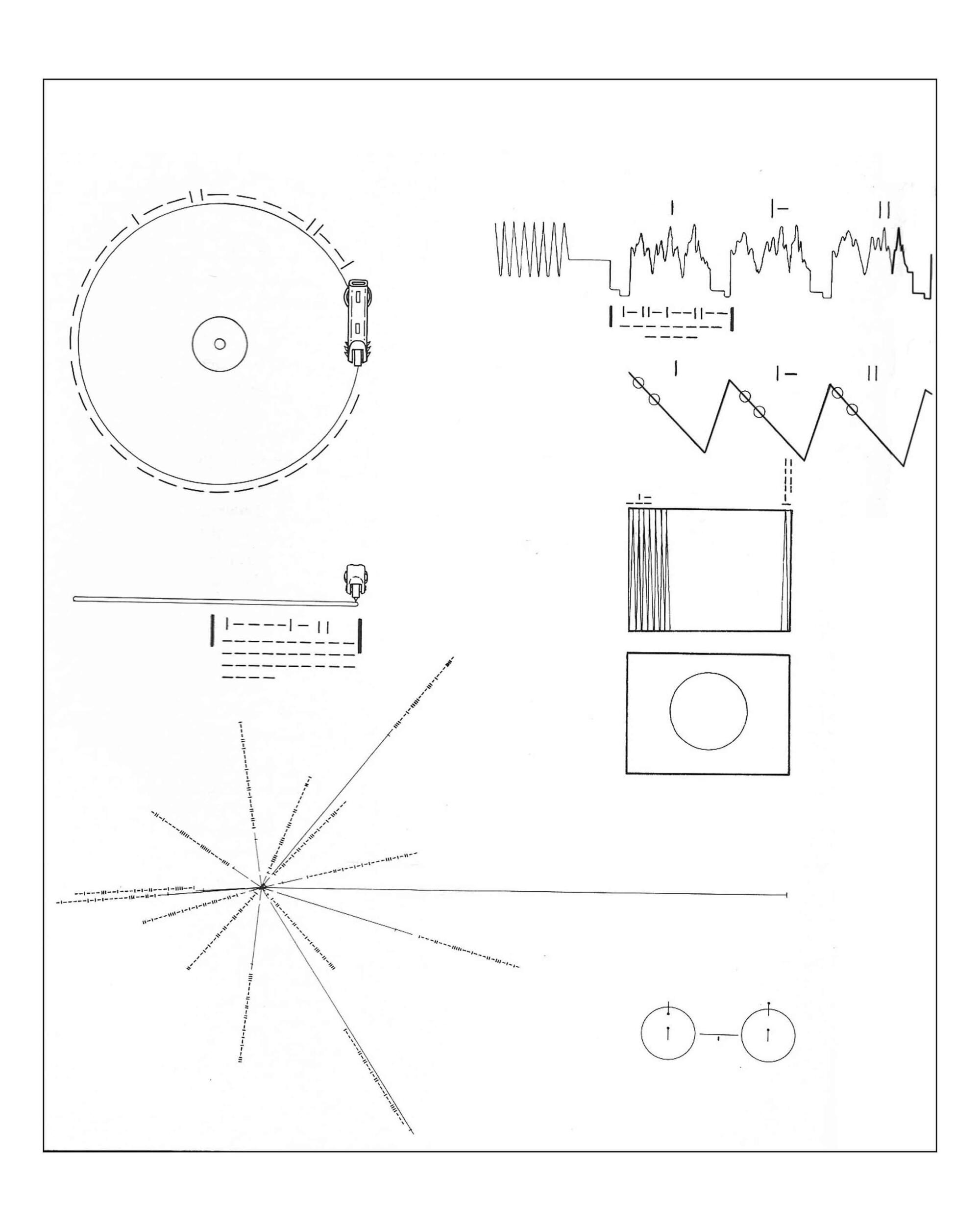

The piece is a metallic album cover affixed to the surface of the Voyager 1 spacecraft. Inside is the Golden Record, a calling card from humanity designed to introduce alien beings to the sounds and images of Earth. Lomberg’s pictorial instructions for playing the record are engraved on the cover, which travels another 912,000 miles away from us every day.

Erosion in space occurs slowly, so the pictures should be readable for at least the next billion years. Long after the last Homo sapiens has perished, Lomberg’s drawings may provide the universe’s most compelling clue that our colorful, complicated species was ever here.

For the last half-century, Lomberg has been at the center of efforts to help inhabitants of this humble planet understand their place in the universe. The process has taken him on a journey as well, one that can’t compare to Voyager in distance but that has revealed truths no less sublime than the images the craft has captured.

Let’s retrace Voyager 1’s path from Earth. Pass the orbit of Saturn, where its trajectory diverged from that of Voyager 2 and its identical copy of the Golden Record. Cross the orbit of 6446 Lomberg, the asteroid named in honor of his contributions to science, and sail by Mars, where the Spirit, Opportunity and Curiosity rovers bear sundials he helped design.

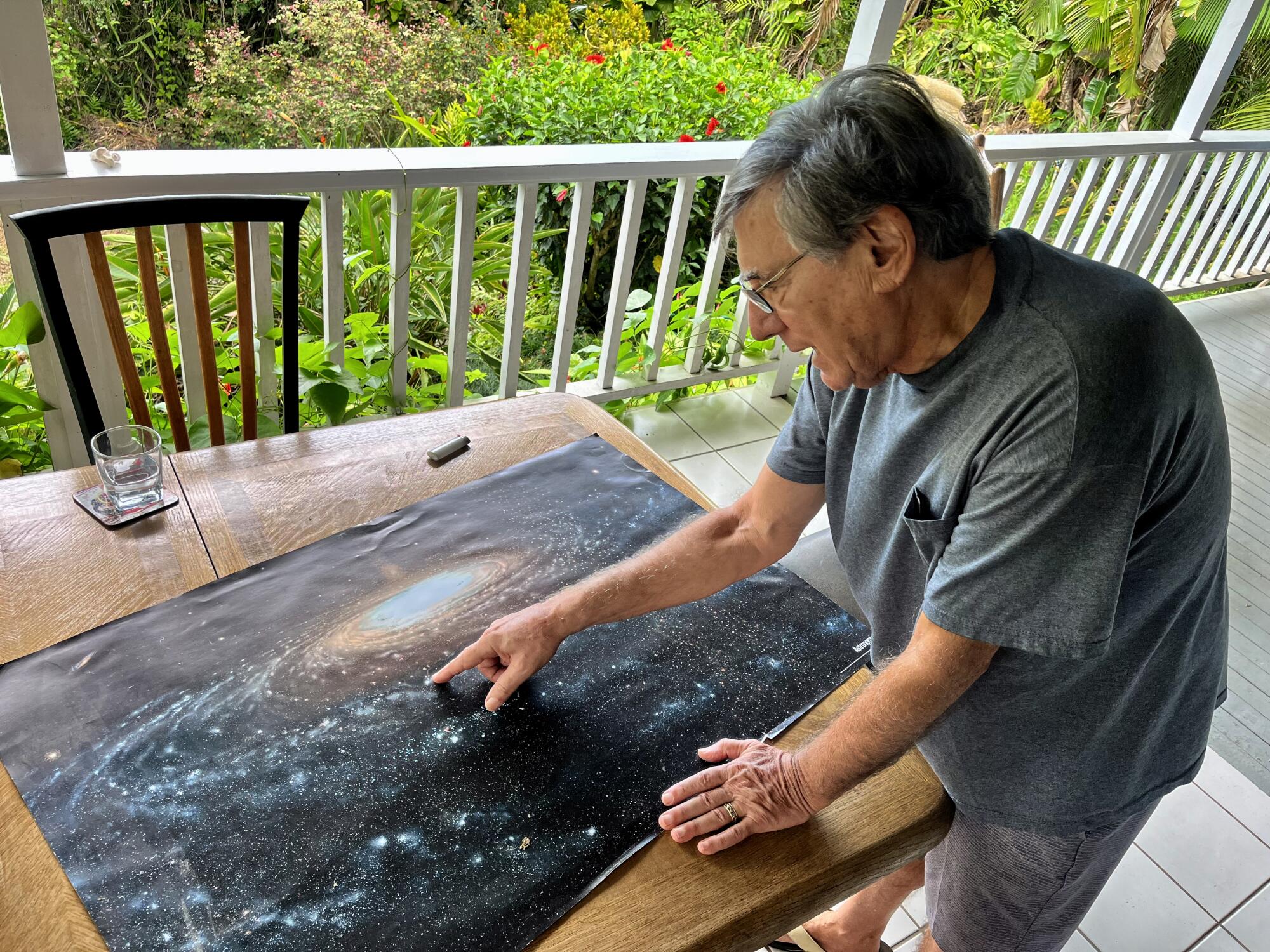

Over the familiar blue dot of our planet, zoom in on a tiny spot in the Pacific — the Big Island of Hawaii, where Lomberg, 74, is on the patio of his family home examining drafts of his latest project, an illustrated biography of the universe.

“The challenge of the Big Bang is that there’s no place standing outside it that you can look at it,” he said, pulling up an illustration on his laptop of bright white shoots of energy emerging from a shapeless shadow. “You sort of have to be in the middle of it.”

“Encyclopedia Cosmologica” is merely the latest in a lifetime of work that attempts to visualize what we can’t truly see, and to communicate with creatures we can’t yet imagine.

Each two-page spread covers 100 million years. Our solar system doesn’t show up until halfway through. Everything since T. rexes fits on the final page. To appreciate the book will require readers to accept themselves as a small part of a giant cosmic production, one in which every star and proton counts. It’s a point of view Lomberg has spent a lifetime realizing through art.

If you can imagine the swirling spiral of the Milky Way galaxy, you are almost certainly picturing a version of Lomberg’s vision of our celestial neighborhood.

From the sky, scientists are dropping devices with parachutes to peer into powerful atmospheric river storms, giving California advance warning.

No photograph exists of the Milky Way as a whole. Were it possible to bend the laws of physics to send a camera into space at the speed of light, that camera would take 26,000 years to reach the galaxy’s outer edges.

“The Milky Way galaxy is notoriously difficult to know what it looks like, because we’re stuck in it. It’s sort of like asking you to draw a detailed picture of your eyes, if mirrors and reflections didn’t exist,” said Ethan Siegel, a theoretical astrophysicist who is working with Lomberg on “Encyclopedia Cosmologica.”

In 1991, the Smithsonian Institution commissioned Lomberg to paint a portrait of the Milky Way for an exhibition at the National Air and Space Museum. He researched the subject for more than a year before picking up a brush. He built a digital map of all the known objects in the galaxy and experimented with different vantage points before settling on the most dramatic view. Using the computer model as a guide, he plotted the celestial objects onto his canvas and then spent another year painting.

Stardust is romantic, but moon dust is a potential hazard as NASA prepares to return to the lunar surface.

The 6-by-8-foot result was, at the time, the most scientifically accurate image of the galaxy. (He has since issued an updated version that includes discoveries made since the original, like exoplanets and the Sagittarius dwarf elliptical galaxy, which intersects the Milky Way.)

It’s not the only time Lomberg’s work has crossed into popular culture. He painted the cover illustration of Carl Sagan’s 1985 novel “Contact” and designed the opening sequence of its 1997 film adaptation.

Lomberg won an Emmy Award for his work on “Cosmos,” a 13-part documentary series hosted by Sagan on public television in 1980. The Emmy sits on a table in Lomberg’s home outside of the town of Captain Cook, so tarnished it looks as if it was fished from the sea. (“This is what the tropics does to a statuette,” he said with a chuckle.)

Lomberg’s art has inspired a generation of space enthusiasts. It was his illustrated version of the cosmos that came to mind when Siegel, his “Encyclopedia Cosmologica” collaborator, imagined the planets and stars as a child.

“He helped shape my views of how I pictured the universe, before we had Hubble images and James Webb Space Telescope images and all of these actual images of what the universe looked like,” Siegel said.

He helped shape my views of how I pictured the universe.

— theoretical astrophysicist Ethan Siegel

All visual art is a way of communicating across time. Lomberg has taken that to an extreme. He was tapped to lead the creation of a time capsule for future visitors to Mars (it’s there now on the husk of the Phoenix lander, near the planet’s north pole).

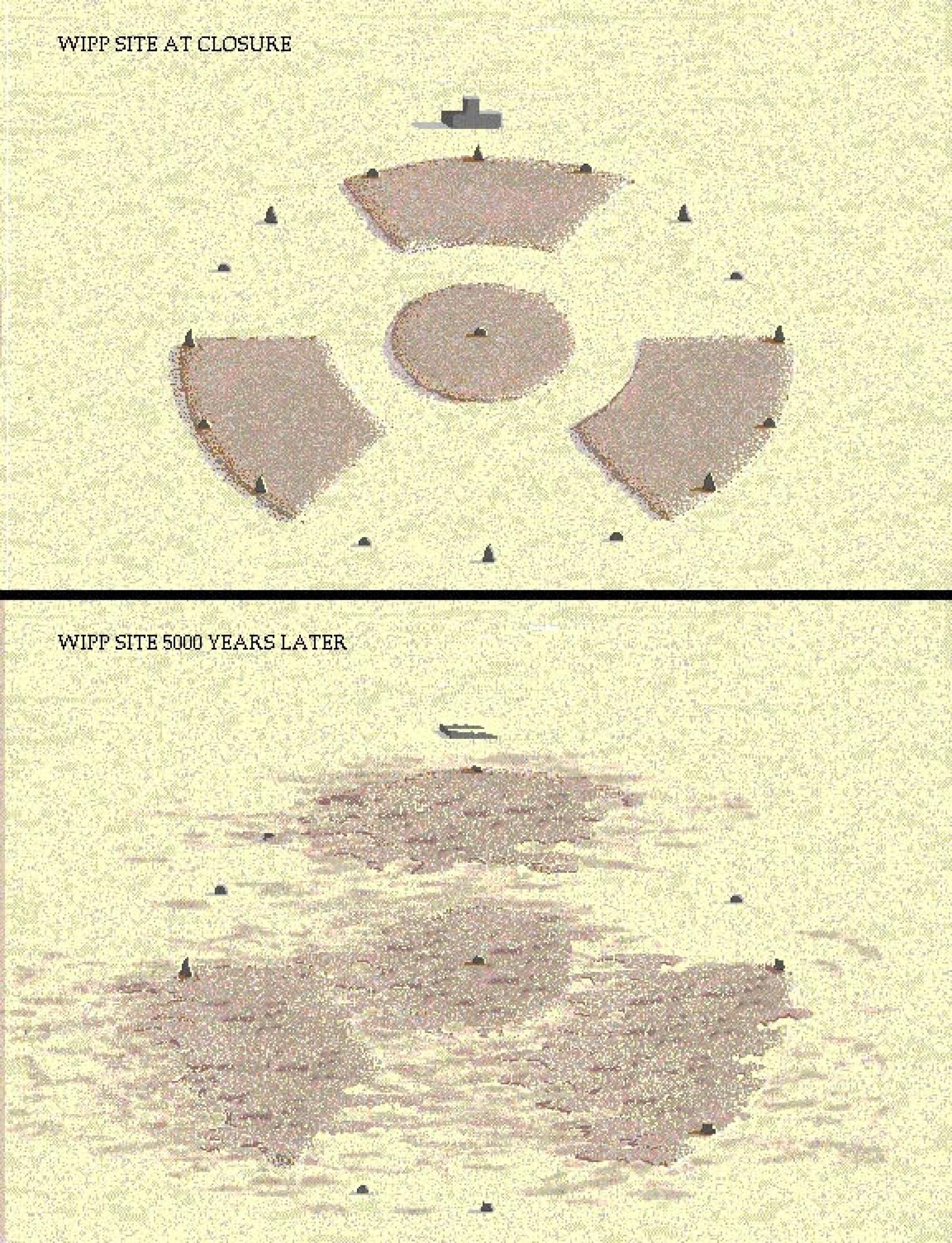

He was part of the team that drafted warning signs for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, a nuclear waste storage facility that will remain radioactive for at least 10,000 years — longer than any human language or symbol has ever endured.

And of course there is the Golden Record, the most famous offering humanity has yet sent into the cosmos purely in the hopes that something — or someone — will find it.

When designing for a different time or species, Lomberg structures the work around principles most likely to be universally shared. Scientists assume that mathematical relationships and the fundamental laws of physics apply everywhere in the universe, and Lomberg looks for the artistic equivalent of these universal truths.

For example, every culture on our planet creates music and language through endless variations of a few simple building blocks and rules. Lomberg believes this instinct to play with patterns could be common to all intelligent beings.

The Golden Record contains Earth’s greatest audio hits — laughter, birdsong, a kiss — as well as images encoded into staticky-sounding waveform data. Lomberg helped choose the selections, lobbying for works with discernible structures: the systole-diastole of a human heartbeat, the crystalline architecture of Bach’s “Third Partita for Unaccompanied Violin.”

Lomberg doesn’t expect aliens to identify the images or sounds, or to share his emotional reaction to Mozart’s “Queen of the Night” aria, his favorite track on the record. But he does believe they will recognize that these aren’t random shapes and sounds. He expects they will realize this is a message, consciously chosen for them by another form of intelligent life.

Lomberg grew up in Philadelphia, the only child of a single mother. He loved drawing and space, specifically the idea that other kinds of life lay somewhere in its immensity. Upon receiving a childhood gift of an encyclopedia, he flipped through the pages looking for the nonexistent section about life on other planets.

“I was always interested in it,” he said. “For me, the question was always: Why isn’t everybody else?”

Jonathan Scott’s “The Vinyl Frontier” tells the story behind the Golden Record on the Voyager.

He graduated from Trinity College with a degree in English in 1969, then performed alternative service at a psychiatric hospital in Boston as a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War. During the day he cleaned wards and tended to patients. After work he painted and read about the stars. He moved to Toronto once his commitment was up, having fallen for the city on his first visit. (Fifteen years later, he moved to Hawaii for the same reason.)

Meanwhile, NASA was preparing to launch its first missions to Jupiter and Saturn in 1972 and 1973. After Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 visited the gas giants, they would become some of the first human-made objects to leave the solar system.

With the Pioneer project, Sagan spotted an opportunity. The Cornell University professor spearheaded an effort to create plaques engraved with a simple map of Earth’s location within the galaxy and the figures of a man and a woman. The identical plaques on the sister spacecraft were the first things humans sent into space for the inhabitants of a different civilization.

The idea electrified Lomberg. He wrote Sagan a fan letter and enclosed some photographs of his paintings. To his surprise, Sagan replied that he would be passing through Toronto on an upcoming trip. Could they meet?

The two spent Sagan’s layover discussing science fiction, art and astronomy. By the time he left to catch his connecting flight, Sagan had offered Lomberg a job illustrating his forthcoming science book, which would eventually be published as “The Cosmic Connection.” Their creative partnership would last until Sagan’s death in 1996 from bone marrow disease.

The two men met at a time of great optimism about the world technology would build. “It’s very hard to recapture what the future seemed like in those days,” Lomberg said. “The universe seemed like a welcoming place.”

That optimism faded in the 21st century. Depictions of the future grew grim — all zombies and apocalypses in fiction, violence and climate catastrophe in the news.

We’re so wary of one another that even the stars seem suspect, he said.

“A lot of people say, ‘Well, aren’t you afraid that sending messages out there is going to invite somebody to come and destroy us?’ I think we’re just projecting our own fears about ourselves,” he said.

“People are just much more fearful of the cosmos than we were back then.”

Paleaku Gardens Peace Sanctuary is a botanic garden overlooking the sea in Captain Cook, not far from the home where Lomberg and his wife, Sharona, an Israeli-born artist, raised their son, Jonathan, and daughter, Merav. He chose it as the site for the first Galaxy Garden, a topiary re-creation of the Milky Way.

The garden measures 100 feet across, with each foot corresponding to 1,000 light-years (or nearly 5.9 trillion miles). His two-dimensional Smithsonian mural can’t convey scale. He wanted to make something that let people feel that vastness, without becoming intimidated by it.

The spiraling hedges are planted with gold dust croton, a leafy green plant dotted with yellow. Each yellow speckle represents 100,000 stars.

Peppering the hedges are plants that signify different astronomical phenomena. Hibiscus flowers are large nebulae, for instance, while white vincas flowers are small ones.

People are just much more fearful of the cosmos than we were back then.

— Jon Lomberg

At the garden’s heart sits a fountain of black volcanic rock: a stand-in for Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy.

UCLA astrophysicist Andrea Ghez, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics in 2020 for her role in the black hole’s discovery, visited the Galaxy Garden in 2009 while doing research at the Keck Observatory telescopes on Mauna Kea.

“There’s something very visceral about it. It brings it back to the human scale, and somehow that affects a different part of your brain, or your understanding of things,” she said. “Even as a scientist, it was really somehow very profound to see it depicted in that way.”

Lomberg has licensed the Galaxy Garden name and layout, and there are now versions in Delaware and Pamplona, Spain. More are on the way, he said.

On the Big Island, volcanic rock pebbles crunched underfoot as Lomberg wandered down a curving hedgerow marked “Orion arm” to a leaf adorned with a plastic jewel that represents our solar system.

Virtually everything we know about the universe can fit, metaphorically speaking, in that single dot on a leaf. There is so much more to explore.

An independent study team assembled by NASA has begun investigating Unidentified Aerial Phenomena (what used to be called UFOs).

That’s why looking to the stars still fills him with optimism, even on a planet that feels increasingly imperiled.

“If we got a signal from some civilization that was clearly much older than ours, that had had high technology and survived,” he said, “that kind of gives you hope that it can be done.”

Lomberg himself doesn’t believe the Golden Records will ever be found — space is simply too big, the Voyagers too small. He has described them as darts thrown randomly in the dark at Madison Square Garden, their chances of striking a target effectively nil.

But the way he sees it, that doesn’t diminish their importance.

This is where Lomberg’s own journey has led him: to a place he has always known instinctively, and that his late collaborator Sagan termed “the cosmic perspective.”

“It’s the idea that we exist on the galactic level and on the atomic level at the same time,” Lomberg explained. “That everything we do, every action we take, reverberates in both directions.”

Lomberg invoked this idea when in February he spoke to students at the San José campus of Avenues, an independent school where he is the first Global Artist in Residence. “We exist so briefly in time and we’re so small in space, and it’s really easy to feel that we don’t matter,” he said. “One of the messages that the cosmic perspective offers is that we do matter, because every scale is important.

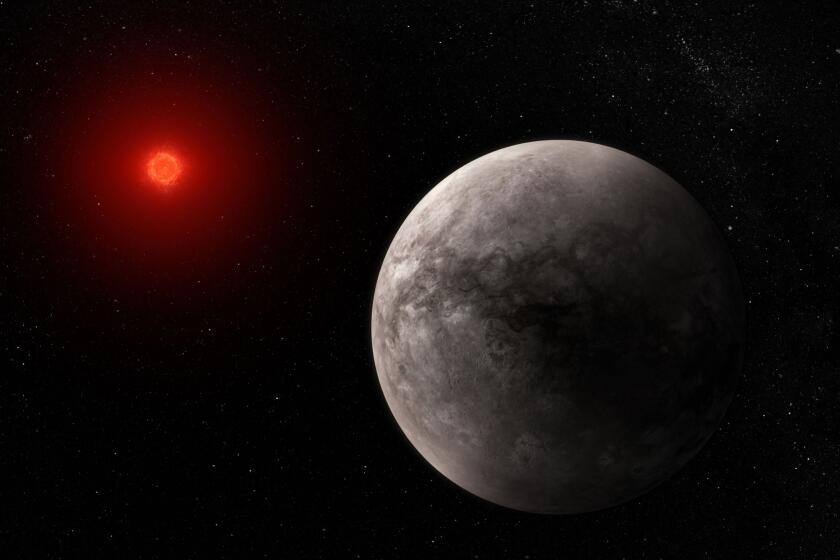

The Webb Space Telescope has found no evidence of an atmosphere at TRAPPIST-1 b, one of the seven rocky, Earth-sized planets orbiting a nearby star.

“You stay in your lane and you don’t worry about the colliding galaxies. You just be significant on your own scale,” he added. “In a funny kind of way, these messages have simultaneously made me feel very small, but also made me feel very big.”

Microscopic cells together form a human; minuscule atoms together form a universe.

All of it counts. It always has.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.