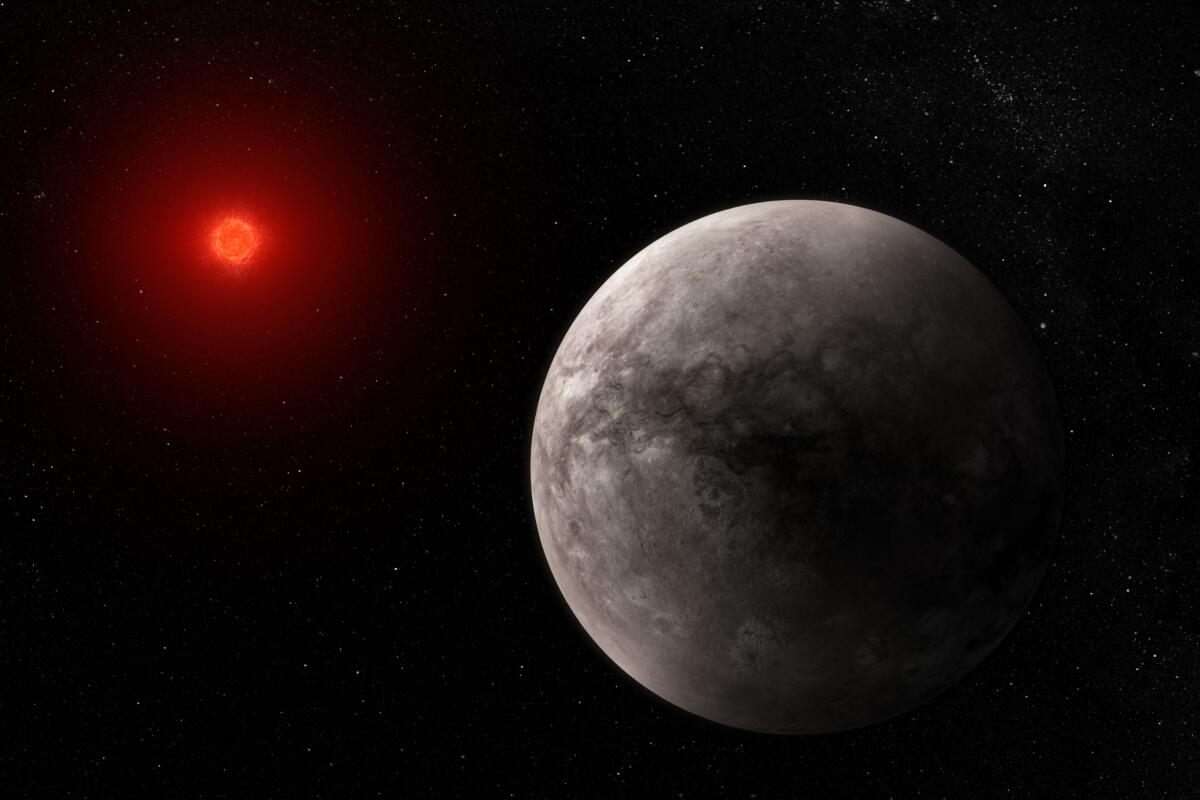

Webb Space Telescope finds no atmosphere at faraway Earth-sized world

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. — The James Webb Space Telescope has found no evidence of an atmosphere at one of the seven rocky, Earth-sized planets orbiting another star.

That doesn’t bode well for the rest of the planets in this solar system, some of which are in the sweet spot for harboring water and potentially life, scientists said.

“This is not necessarily a bust” for the other planets, said MIT astrophysicist Sara Seager, who wasn’t part of the study describing the findings. “But we will have to wait and see.”

The Trappist solar system — a rarity with seven planets about the size of our own — has enticed astronomers ever since they spotted it just 40 light-years away. That’s close by cosmic standards; a light-year is about 5.8 trillion miles. Three of the seven planets are in their star’s habitable zone, making this star system even more alluring.

The NASA-led team reported little if any atmosphere exists at the innermost planet. The results were published Monday in the journal Nature.

The lack of an atmosphere would mean no water and no protection from cosmic rays, said lead researcher Thomas Greene, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Ames Research Center.

As for the other planets orbiting the small, feeble Trappist star, “I would have been more optimistic about the others” having atmospheres if this one had, Greene said.

If rocky planets orbiting ultracool red dwarf stars like this one “do turn out to be a bust, we will have to wait for Earths around sun-like stars, which could be a long wait,” said MIT’s Seager.

Because the Trappist system’s innermost planet is bombarded by solar radiation — four times as much as Earth gets from our sun — it’s possible that extra energy is why there’s no atmosphere, Greene noted. His team found temperatures there hitting 450 degrees Fahrenheit on the side of the planet constantly facing its star.

Using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, an international team of scientists has tracked two planets crossing in front of the same star at the same time -- discovering that these worlds are both rocky and have comparatively thin atmospheres.

By using Webb — the largest and most powerful telescope ever sent into space — the U.S. and French scientists were able to measure the change in brightness as the innermost planet moved behind its star and estimate how much infrared light was emitted from the planet.

The change in brightness was minuscule since the Trappist star is more than 1,000 times brighter than this planet, so Webb’s detection of it “is itself a major milestone,” the European Space Agency said.

More observations are planned not only of this planet, but the others in the Trappist system. Looking at this particular planet in another wavelength could uncover an atmosphere much thinner than our own, although it seems unlikely it could survive, said Taylor Bell of the Bay Area Environmental Research Institute, who was part of the study.

Could the TRAPPIST-1 star system host a life-friendly planet?

Further research could still uncover an atmosphere of sorts, even if it’s not exactly like what’s seen on Earth, said Michael Gillon of the University of Liege in Belgium, who was part of the team that discovered the first three Trappist planets in 2016. He did not take part in the new study.

“With rocky exoplanets, we are in uncharted territory” since scientists’ understanding is based on the four rocky planets of our solar system, Gillon said.

Launched in late 2021 to an observation post 1 million miles away, Webb is considered the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, which has been orbiting Earth for more than three decades.

In the past, Hubble and the Spitzer Space Telescope scoured the Trappist system for atmospheres, but without definitive results.

“It is just the beginning, and what we can learn with the inner planets is going to be different from what we can learn from the other ones,” said MIT’s Julien de Wit, who was not involved in the study.