Coronavirus Today: Prioritizing equity after the pandemic

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, March 7. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

Nobody wants to live in a state of emergency forever. But when the clock runs out on the federal government’s COVID-19 emergency declarations about two months from now, some things are likely to get worse.

Unfortunately, these kinds of problems won’t affect all Americans equally. While the majority of us celebrate a more complete return to normal life, people in vulnerable communities will bear most of the risk inherent in having fewer precautions.

Perhaps that should seem obvious by now. It’s no secret that pandemics exacerbate health disparities. Those who had only a general sense of this before the coronavirus arrived have seen it firsthand over the last three years.

During most of that time, people of color (except for Asian Americans) have caught COVID-19 at higher rates than their white peers, according to nationwide data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The picture was largely the same for COVID-19 deaths until vaccines became available and helped level the playing field. In California, Latino and Black residents account for a disproportionately high share of COVID-19 deaths.

A report last summer from the Kaiser Family Foundation found that compared with white Americans, the risk of catching the coronavirus was about 1.5 times higher for Latino Americans, Native Americans and Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders. Worse, the risk of dying of COVID-19 was twice as high for members of those groups and for Black Americans than it was for their white counterparts. Those calculations controlled for age, which is important since health risks vary by age, and white Americans skew older than members of other racial and ethnic groups.

The federal government helped reduce some of these disparities by making it easier for all Americans to access COVID-19 vaccines, tests and treatment at little to no cost. It also expanded access to healthcare in general by offering states more money to fund their Medicaid programs for disabled and low-income Americans. In exchange, the states that took the money were largely prevented from knocking anyone off their rolls, a policy that extended health coverage to about 20 million additional Americans, according to KFF.

But those protections will end on March 31. In April, states will once again be able to disenroll Medicaid patients. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services projects that about 15 million people — including 5.3 million children — will lose their health insurance as a result.

Among them are 6.8 million people who actually will be eligible for Medicaid but will lose coverage anyway because they’ll have trouble filling out the necessary paperwork in time or face other administrative hurdles. Latino Americans will account for 35% of these “churning” victims, and Black Americans will make up another 15%, HHS says.

People who lose their health coverage are less likely to get preventive care and more likely to seek treatment in overburdened hospital emergency rooms, if they go anywhere at all. Those with diabetes, heart disease or other chronic conditions will find it more difficult to manage them — and if they do go to a doctor, they may wind up saddled with a bill they can’t pay.

They’ll also have to start paying for COVID-19 care. Medicines, vaccines and tests may remain free for a while, but once the government’s stockpile runs out, they’ll be on their own. These problems will have an outsize impact on undocumented immigrants, since 46% of them are uninsured, according to KFF.

Free COVID tests may no longer be available to people without insurance after the federal declaration of emergency ends in May.

”This is a tragedy in its own right and is likely to expand racial health inequalities connected to COVID,” Wendy Netter Epstein, a professor at DePaul University College of Law, and Daniel Goldberg, a public health ethicist at the Center for Bioethics and Humanities at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, argue in our opinion pages. “It will also have broader impacts on the community and the economy as COVID will spread, workforce shortages will continue and burdens of long COVID will increase.”

But there are things states can do to counteract these inequities, Netter Epstein and Goldberg write.

For starters, states can make it easier for residents to maintain their Medicaid coverage if they are eligible for it. California, for instance, has launched an effort to let the state’s 15.4 million Medi-Cal recipients know that they’ll need to renew their enrollment and encourage them to do so. The campaign will reach out to people in 19 languages. (If you’re on Medi-Cal, you can sign up to receive updates about the reenrollment process at www.KeepMediCalCoverage.org.)

Arkansas, on the other hand, is aiming to speed through the exercise in half the available time. That’s not exactly conducive to keeping people from falling through the cracks, health policy experts say. For Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders, that seems to be the point. Her goal is to “move people from government dependency to a lifetime of prosperity,” her spokesperson told Politico.

States can also help residents who lose their Medicaid coverage find low-cost (or no-cost) policies on the Affordable Care Act marketplace, Netter Epstein and Goldberg write. If Rhode Island residents lose their Medicaid eligibility, the state will sign them up for a new plan. In Maryland, navigators are available to help residents find private insurance they can afford.

A state committed to reducing health disparities will need to look beyond issues of access, Netter Epstein and Goldberg add. Ensuring paid sick leave, offering food assistance and implementing universal basic income requirements would help counteract the inequities worsened by the pandemic.

“Moving out of the declared emergency doesn’t mean we should forget that the burden of COVID is borne disproportionately by vulnerable communities,” the pair write. “Policies to prevent worsening COVID-driven inequities can — and should — be enacted now.”

By the numbers

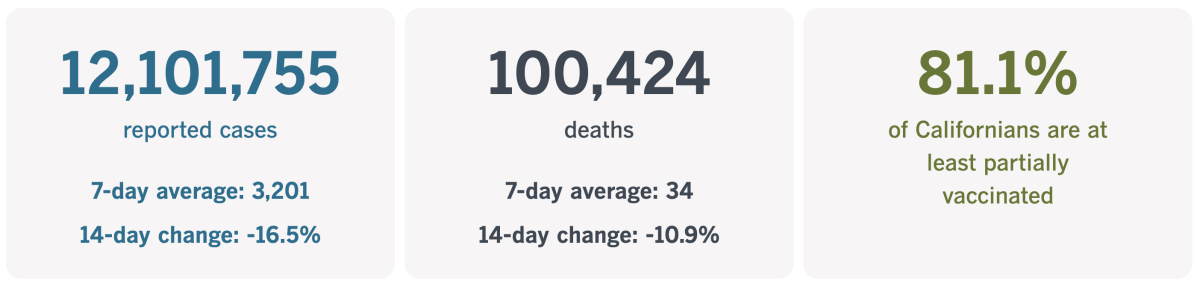

California cases and deaths as of 5 p.m. on Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Taking a closer look at food insecurity

While we’re on the topic of ways to prevent backsliding on health disparities, let’s look at what’s already happening with a program designed to reduce food insecurity.

This month, nearly 5 million low-income Californians will see a dramatic decrease in the amount of government assistance they receive to buy food. Those losses will average about $82 per person per month, and the households they’re part of will see their grocery budgets fall by about $200 per month.

Delia Priscilla Ortega Darden is one of those people. The 64-year-old has multiple sclerosis and other health problems that prevent her from working. So she lives in her car and relies on programs like CalFresh, the state’s version of the federal program that used to be known as food stamps.

Ortega Darden credits CalFresh for maintaining her access to fresh fruits and vegetables. The healthy produce has helped her deal with the muscle cramps that develop in her legs. “My whole health has been better because of it,” she told my colleague Mackenzie Mays.

But soon, she’ll receive $95 less each month to spend on groceries. To stretch her budget, she said she’ll have to allocate more of her money to inexpensive items like bologna and count on food banks to make up the nutrition gap.

This is another downside of ending the various pandemic states of emergency. Congress began pumping more money into the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, in March 2020 to help Americans cope with the economic upheaval wrought by the pandemic. Now that the country seems to have returned to “normal,” Congress decided its budget for SNAP benefits could return to normal too.

The timing could hardly be worse. The cost of living is on the rise, forcing people to spend more on gasoline, housing and energy bills as well as food. But California officials are anticipating a $22.5-billion budget deficit for the upcoming fiscal year, and Gov. Gavin Newsom has shied away from committing to any new ongoing spending.

Some state legislators have other ideas. Sen Caroline Menjivar (D-Panorama City) introduced a bill that would increase the minimum monthly CalFresh benefit from $23 to $50. That would cost the state more than half a billion dollars a month, but Menjivar said the bill would pay for itself by staving off more expensive problems, such as homelessness.

Alleviating food insecurity “can prevent so many different things. It’s about ensuring that our most vulnerable families don’t fall further down into poverty,” she said.

Officials with California’s Department of Social Services saw this crisis coming and has been warning about it for months. Without extra funds to chip in, however, they’ve held out hope that food banks would be able to pick up the slack.

Not likely, said Stacia Hill Levenfeld, chief executive of the California Assn. of Food Banks. The rollback in CalFresh benefits is only part of the problem. At some point, the electronic benefit transfer cards that help secure food for low-income children will expire too. Combined, they amount to a 30% loss to the food safety net here, Hill Levenfeld said.

“There’s no way that food banks alone can fill the gap,” she told Mays.

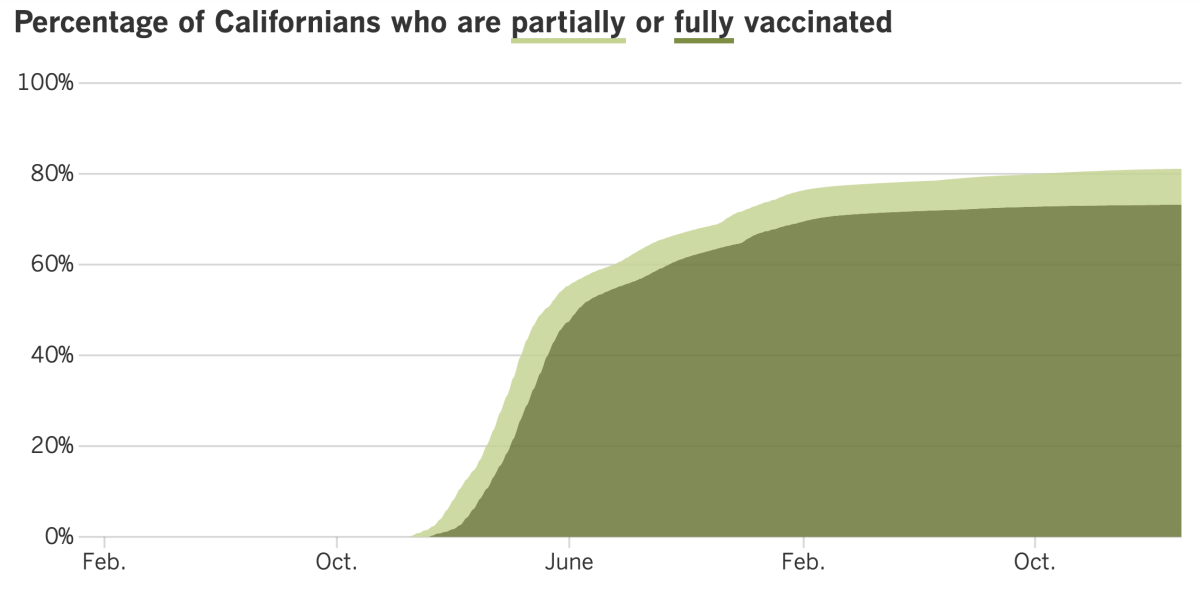

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

Now that California’s state of emergency is over, health officials have taken a fresh look at their COVID-19 prevention policies and decided that some changes are in order.

For starters, they’ve relaxed their guidance on how soon people with coronavirus infections can end their isolation periods. Currently, the state advises people to let five days pass after their first COVID-19 symptoms appeared or they first tested positive for an infection, then test themselves again. If the result is negative, they can exit isolation as long as they wear a mask in public places until they reach Day 10. If the test results are still positive, they should keep trying until Day 10, at which point they can rejoin society so long as they’ve been fever-free for at least a day and their other symptoms have improved.

Starting Monday, that regimen will be greatly simplified. As long as a person has gone a full day without a fever and their other symptoms are tapering off, they can end their isolation on Day 5 without needing to test first, the state says. However, if a person wants to stop wearing masks in public prior to Day 10, they’ll need to produce negative tests on two consecutive days.

That’s just one of several changes. On April 3, the California Department of Public Health will drop its COVID-19 vaccination requirement for healthcare workers. That applies to people in hospitals, clinics, long-term care facilities and other traditional medical settings, as well as to those who work in detention centers and correctional facilities. Even so, the state noted that “most health care workers” would still be vaccinated thanks to federal vaccination rules.

In addition, indoor masking will become optional in healthcare settings, correctional facilities, emergency shelters and other high-risk settings.

Dr. Tomás Aragón, California’s public health director, thanked Californians for the sacrifices they’ve made and said it was time to reap the benefits of their patience, persistence and hard work.

“We have now reached a point where we can update some of the COVID-19 guidance to continue to balance prevention and adapting to living with COVID-19,” he said in a statement.

Californians have been doing a pretty good job of maintaining their coronavirus progress. The CDC reports that most of California has a low COVID-19 community level. The only counties in the “medium” category are the cluster of Merced, Mariposa, Tuolumne and Stanislaus in the central part of the state and seven contiguous ones further north (Lake, Napa, Yolo, Solano, Sacramento, Placer and El Dorado).

In Washington, D.C., the Biden administration is seeking more than $1.6 billion to help prosecute alleged fraudsters who took advantage of the federal government’s massive COVID-19 pandemic relief programs.

Biden and his predecessor, Donald Trump, signed nearly $6 trillion worth of relief measures for individuals, businesses, and state and local governments. Scammers took advantage, often using fake identities to claim unemployment and other benefits. The U.S. Department of Labor said as much as $164 billion was paid out inappropriately.

Biden’s request includes $600 million to increase the number of Justice Department anti-fraud “strike forces” from three to at least 13. At least $300 million more would allow inspector generals’ offices to hire more investigators. Other funds would upgrade government systems to prevent identity theft and to bolster IdentityTheft.gov, a site maintained by the Federal Trade Commission that’s geared toward assisting victims.

Administration officials acknowledged that Congress has been reluctant to approve pandemic-related spending in recent months, but they hope these funds will be viewed as an investment. Last year, the U.S. Secret Service recovered $286 million from fraudsters who received improper loans from the Small Business Administration.

“A dollar smartly spent here will return to the taxpayers, or save, at least $10,” said Gene Sperling, the White House American Rescue Plan coordinator.

Speaking of huge amounts of money, a recent survey found that the already huge pay gap between CEOs and their workers widened further during the pandemic.

The Institute for Policy Studies, a progressive think tank, examined pay at 300 companies that had the lowest median wages in 2020. The gulf between those wages and the money earned by top executives grew in 2021. On average, the ratio of executive pay to worker pay rose from 604 to 1 in 2020 to 670 to 1 in 2021. In 49 companies, CEOs made 1,000 times more money than their typical worker.

IPS also determined that the average pay of median workers increased from $20,412 in 2020 to $23,968 in 2021. During the same period, the average pay of CEOs rose from $8.1 million to $10.6 million.

My colleague Michael Hiltzik explained that some of this inequity was made possible by corporate boards that opted to let leaders off the hook for the horrendous financial performance of the pandemic’s worst days. The board of Chipotle, for instance, ignored the eatery’s record in the last three months of 2020, allowing CEO Brian Niccol to earn $38 million. Had all 12 months counted, he would have made $14.8 million, less than half as much.

“If a company has a good year, it’s all about the management team and the CEO driving it,” Rosanna Landis Weaver, lead author of a new report on the most overpaid corporate executives, told Hiltzik. “When they don’t do well, it’s all about ‘external factors.’”

And finally, Pfizer and BioNTech have asked the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to authorize a booster dose of its updated COVID-19 vaccine for the youngest Americans. Currently, children ages 6 months to 4 years can get the Omicron-targeting vaccine as the final shot in the three-shot primary series. If the FDA agrees, a fourth shot would be made available to those who completed the initial series, some of whom did so before the new formulation was available.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Will people in L.A. County still have to wear masks in healthcare settings once the county’s health emergency ends?

Yes, but only for a few days. And not for the reason you might think.

The mask mandate for healthcare facilities comes from the California Department of Public Health, not from L.A. County. So it’s up to state officials to decide when it’s safe to loosen that rule. And the answer they’ve come up with is April 3.

As mentioned earlier, CDPH announced Friday that it would amend its public health officer order related to indoor masking in hospitals, urgent care clinics, medical offices, nursing homes and other long-term care facilities so that masks would no longer be required there. The changes will take effect three days after L.A. County’s COVID-19 emergency declaration ends on March 31.

There’s no connection between the two dates. Nor is there a connection between April 3 and Feb. 28, the last day of California’s state of emergency. That’s because CDPH can make changes to its public health orders whenever it wants, and the state’s emergency (or non-emergency) status has nothing to do with it.

That said, giving the public a month’s notice about the upcoming change in mask rules will give public health departments and medical facilities time to come up with new policies for a mandate-less future, state officials said.

The health department added that its advice on mask use for individuals hasn’t changed. In L.A. County and other counties with low COVID-19 community levels, people who could become seriously ill if they catch the coronavirus should “consider wearing a mask in crowded indoor public places,” CDPH says. All others “can wear a mask based on personal preference, informed by their own personal level of risk.”

State health officials also recommend wearing a mask in public if you have symptoms of a respiratory disease or if you’ve been exposed to someone who tested positive for a coronavirus infection in the last 10 days. If you’re on an airplane, bus or other indoor forms of public transportation, mask use should also be considered.

CDPH adds that if you do wear a mask, “surgical masks or higher-level respirators (e.g., N95s, KN95s, KF94s) with good fit are highly recommended.”

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

A milestone is approaching that, in some ways, feels more significant than the winding down of so many state and local emergency declarations.

On Friday, Johns Hopkins University’s lauded COVID-19 Dashboard will issue its final update of coronavirus data from around the world.

It’s hard to overstate the dashboard’s importance, especially in the earliest days of the outbreak when reliable information was hard to come by. Indeed, it was that data vacuum that prompted infectious disease modeler Lauren Gardner to suggest that her graduate student Ensheng Dong create a map to track the virus’ spread. Dong, who was worried about his relatives in China’s Shanxi province, built the initial website in a day.

The JHU dashboard was up and running long before agencies like the CDC and the World Health Organization built trackers of their own. Gardner has said she figured the data her team collected and shared would be valuable, “but I guess I didn’t expect to be the sole source of it.”

The COVID-19 Dashboard has been viewed more than 2.5 billion times since it went live in January 2020, according to Johns Hopkins. But now government health departments are sharing their data less frequently, and the available data are less reliable since people increasingly diagnose their own infections with at-home tests. Those trends — along with the fact that the CDC built out its own comprehensive COVID Data Tracker — persuaded Johns Hopkins that it was time to retire its dashboard.

All of the raw data collected between Jan. 22, 2020, and March 10, 2023, will remain available to the public.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in various ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, as well as resources for people experiencing domestic abuse.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.