Column: While workers struggled during the pandemic, CEO pay went up, up, up

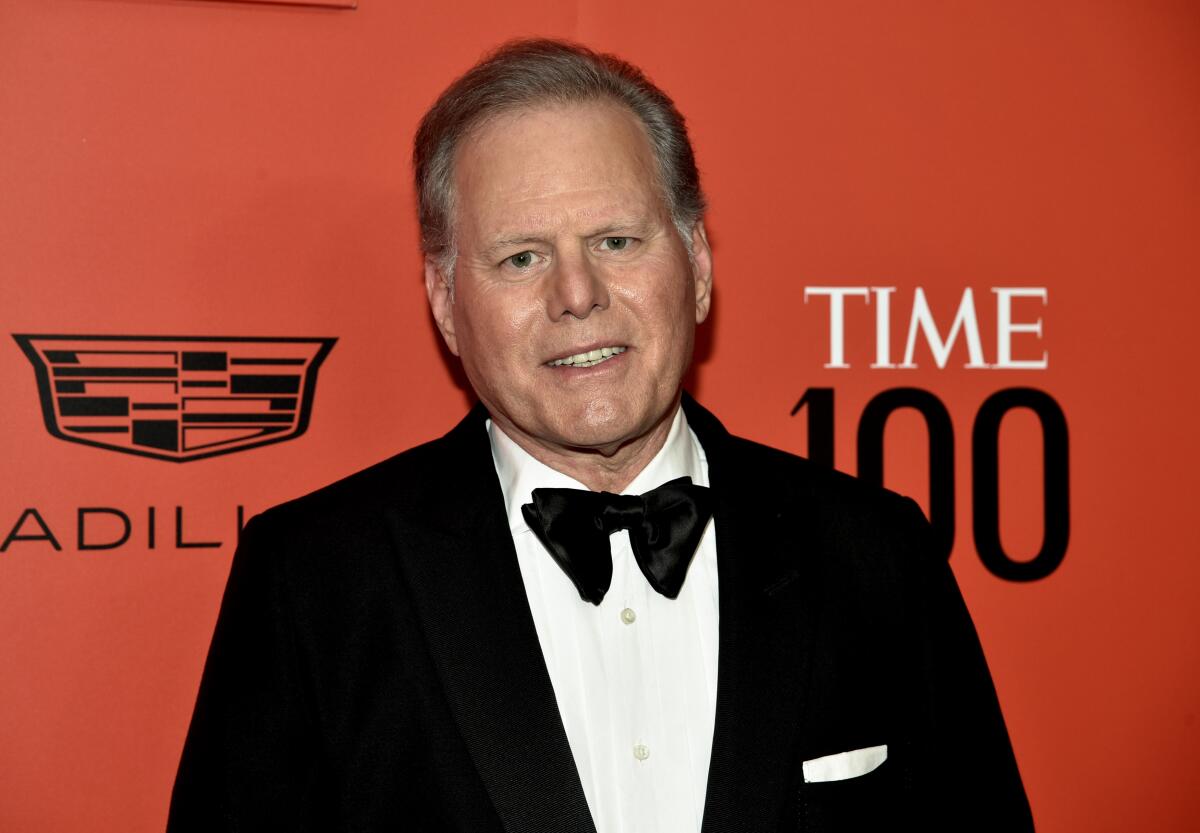

If the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and the lyricists Gus Kahn and Raymond B. Egan could come back from the grave, they might seek out and thank Warner Bros. Discovery CEO David Zaslav for validating their line about how “the rich get rich and the poor get poorer.”

That’s because Zaslav just scurried to the top of the list of America’s most overpaid chief executives published annually by the consumer advocacy group As You Sow.

In 2021, when the total shareholder return of Zaslav’s company (then known as Discovery) declined by 22%, Zaslav’s compensation rocketed up to $246.6 million from $37.7 million the year before, a gain of 554%.

If a company has a good year, it’s all about the management team and the CEO driving it. If they don’t do well, it’s all about ‘external factors.’

— Rosanna Landis Weaver, As You Sow

The ratio of Zaslav’s pay to that of the median Discovery employee was 2,972 to 1; the average among the Standard & Poor’s 500 companies was 324 to 1 — still excessive, but not a patch on Zaslav’s achievement.

Total shareholder return mostly encompasses share price changes and dividends.

(By the way, Shelley observed that “the rich have become richer and the poor have become poorer” in his 1821 essay “A Defence of Poetry”; Kahn and Egan instilled it in American culture by writing “the rich get rich and the poor get poorer” into their 1921 song “Ain’t We Got Fun?”)

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Zaslav is the champion among American CEOs in their race to the top. Unfortunately, the process by which he acquired his astounding pay package is emblematic of a serious pathology in American business.

Corporate boards have found ways to circumvent efforts to rein in executive pay through tax rules, shareholder voting options, and moral suasion.

Even the unique economic head winds of the COVID pandemic failed to put a leash on the rise of CEO pay — boards simply used the pandemic as an excuse to rejigger executive pay packages so they wouldn’t be penalized for business conditions said to be beyond their control.

The CEO pay issue may come into sharp relief due to a pending court ruling on the lavish compensation deal that Tesla awarded CEO Elon Musk.

Plaintiffs in a shareholder lawsuit filed in Delaware Chancery Court estimate that the package, granted by a “supine board,” could be worth nearly $56 billion, making it the “largest compensation plan in history.” A ruling on the lawsuit could come any day now.

CEOs are the ultimate beneficiaries of a “heads I win, tails you lose” ethos in corporate management.

“If a company has a good year, it’s all about the management team and the CEO driving it,” says Rosanna Landis Weaver, lead author of As You Sow’s report. “When they don’t do well, it’s all about ‘external factors.’”

The rail strike is looming because the railroads are refusing to give their workers paid sick days, even though they are swimming in profits. Congress should let workers use their leverage.

The most flagrant example of this creed may have occurred at Chipotle Mexican Grill, which like other fast-food restaurants was seriously affected by pandemic-driven closures.

As I reported in 2021, Chipotle’s board gifted its three top executives, including CEO Brian Niccol, with pandemic bonuses totaling $64.4 million. It did this by removing the three months in 2020 in which the company was most severely affected from the calculation of corporate financial performance underlying the executives’ pay packages.

As a result, Niccol’s pay more than doubled to $38 million in 2020 from $16.1 million in 2019; without the recalibration, he would have suffered a pay cut to $14.8 million.

In general, the average pay of the 100 most overpaid CEOs in As You Sow’s most recent report rose by 30.6% to $38,192,249, up from the $29,233,020 average in the previous year’s report.

Huge pay packages for CEOs are routinely justified as rewards for the performance of their companies. The truth is that there appears to be no connection.

If anything, there’s an inverse connection. “The bottom fifth of companies by equity incentive award outperformed the top fifth by nearly 39% on average on a 10-year cumulative basis,” the consulting firm MSCI found in 2017 after a survey of its clients.

Directors on their boards’ compensation committees often seem to be blind to this reality. They’re often current or retired CEOs themselves, and therefore accustomed to normalizing outsized pay based on their own personal experience.

They often persuade themselves that performance standards imposed on CEOs to trigger big pay awards will align pay with shareholder interests, but may not notice that those standards are subjective, not objective.

The relentless bloat in CEO pay during good times and bad also points to how corporate America breeds economic inequality. During the pandemic year of 2021, which ended with a surge in inflation that persisted into 2022, the CEO-worker pay gap at low-wage companies widened.

That’s according to a survey by the Institute for Policy Studies, a progressive think tank, of the 300 companies paying the lowest median wages in 2020.

The average gap between CEO and median pay rose to 670 to 1, from 604 to 1 in 2020. Among the 106 companies in the sample where median worker pay in 2021 failed to keep pace with inflation, 67 instituted stock buybacks — which help to drive CEO pay higher — totaling $43.7 billion. The leaders in this club, IPS found, were retailers Lowe’s, Target and Best Buy.

Leon Cooperman is the latest American billionaire to complain about a wealth tax and “vilification of the rich.”

The spring proxy season, when public companies disclose their top executives’ pay for the previous year, is typically when the scale of CEO gluttony gets aired. That usually begins with the raw numbers, including changes from prior years. As You Sow adds context to this process by calculating “excess pay” — that is, excess over what they should have received according to consistent standards and ranking CEOs by that metric.

This year, Zaslav is joined on the roster of the 25 most overpaid CEOs by the leaders of Estee Lauder, Intel, Las Vegas Sands, Coca-Cola, JPMorgan Chase and Walt Disney (though the Disney CEO in 2021, Bob Chapek, was ousted last December).

The rankings are based on a three-pronged measure encompassing a calculation of five-year shareholder returns by HIP Investor, a consulting firm specializing in environmental, social and corporate governance issues; the magnitude of shareholder votes opposing the CEO’s pay; and the CEO-to-median worker pay ratio required to be disclosed in every company’s annual public filings. They’re then combined into a single ranking.

By that measure, Zaslav deserved to collect about $13.9 million in 2021, implying that he was overpaid by about 94%.

Of the three factors, the shareholder vote may be the most interesting. The 2010 Dodd-Frank Act gave shareholders a say on executive pay, albeit a relatively toothless one — the vote can only be advisory, not binding.

Still, there are clear indications that shareholders are increasingly discontented with the tens or hundreds of millions of dollars being siphoned off to the CEOs.

At first glance, the anti-CEO shareholder vote at some companies with bloated CEO pay may look modest, but that’s because many of those companies have heavy insider shareholdings or two-tier share voting rights that give insiders multiple votes per share.

As You Sow focuses on the say-on-pay votes by large institutional investors, which have to disclose their votes in public filings to the Securities and Exchange Commission.

That gives a more accurate picture of shareholder opinion, As You Sow says. The cosmetics firm Estee Lauder, whose CEO Fabrizio Freda ranks second to Zaslav in the excess pay rankings, reported that 91% of its shares were voted in support of Freda’s pay. That reflected the stock ownership of the Lauder family, whose shares carry 10 votes each. The vote of institutional investors, whose shares carry one vote each, went 70% against Freda.

A California judge got it right: Prop. 22, California’s gig economy law, outrageously trampled on employee rights.

Some big institutions have turned increasingly negative on executive pay packages, especially those with the red flags of excessiveness. CalPERS, the largest public pension fund in the country, voted against 79% of As You Sow’s 100 most overpaid CEOs in 2022, up from 76% the year before.

The University of California pension fund voted against the CEO pay of 83% of S&P 500 companies and 90% of the Overpaid 100. Among its targets was Tim Cook, the CEO of Apple, who received about $99 million in 2021 and again in 2022. UC’s objection was that the vast bulk of Cook’s pay was not related to the company’s performance but would be paid out over time no matter what.

Private institutional investors such as BlackRock and Vanguard tend to be more complaisant about CEO pay — except for European funds. “They vote against U.S. CEOs at a much higher rate,” Weaver told me. “They know that there are many CEOs in many countries working very hard without requiring excess pay.”

Excessive CEO pay is largely a U.S. phenomenon. Consider the global auto industry: In 2021, As You Sow documents, Volkwagen’s revenues were more than twice those of Ford and General Motors. The German company’s CEO collected $9.1 million in compensation; Ford’s CEO received $22.8 million (more than twice VW’s) and GM’s CEO received $29.1 million (three times VW’s).

For obvious reasons, corporate managements absolutely detest these sorts of analyses and generally respond to them with maximal defensiveness.

Warner Bros. Discovery, for example, defended Zaslav’s pay package to Reuters by asserting that the CEO would have to reach ambitious performance goals to collect the money awarded through equity grants. “The vast majority of the headline number is theoretical,” a spokesman said.

Yet it’s more likely that the equity grants, which tend to constitute the bulk of outsized compensation packages, understate the executives’ ultimate pay. More often than not, according to a study by Josh Bivens and Jori Kandra of the labor-affiliated Economic Policy Institute dating back to 1965, executives’ realized compensation — that is, the amount they received by exercising stock and option grants — has exceeded the reported value of those grants the year they were awarded.

Can anything rein in CEO pay? A prohibition on deductions for cash executive pay over $1 million, instituted in 1994, spurred the rise in performance-based equity awards because they were exempted from the cap. The Republicans’ 2017 tax cuts repealed the exemption, but companies have responded by simply increasing the cash component of pay packages.

Shareholder votes may have begun to yield fruit. Pay packages at Activision Blizzard, Chipotle and Hilton, among other corporations, were cut after strong shareholder votes against them; but it’s unclear how much the votes had to do with the pay cuts, since some of those companies also suffered business reversals that might have triggered the cuts anyway. At Apple, Cook recently got a 40% pay cut, to $49 million; the company said he asked for the cut after shareholder approval for his pay package dropped sharply.

Weaver takes heart from the ever-increasing public attention being paid to exorbitant CEO pay. “It’s a very popular issue and not particularly a partisan issue. I’m hopeful we’re going to end the ‘greed is good’ era, eventually.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.