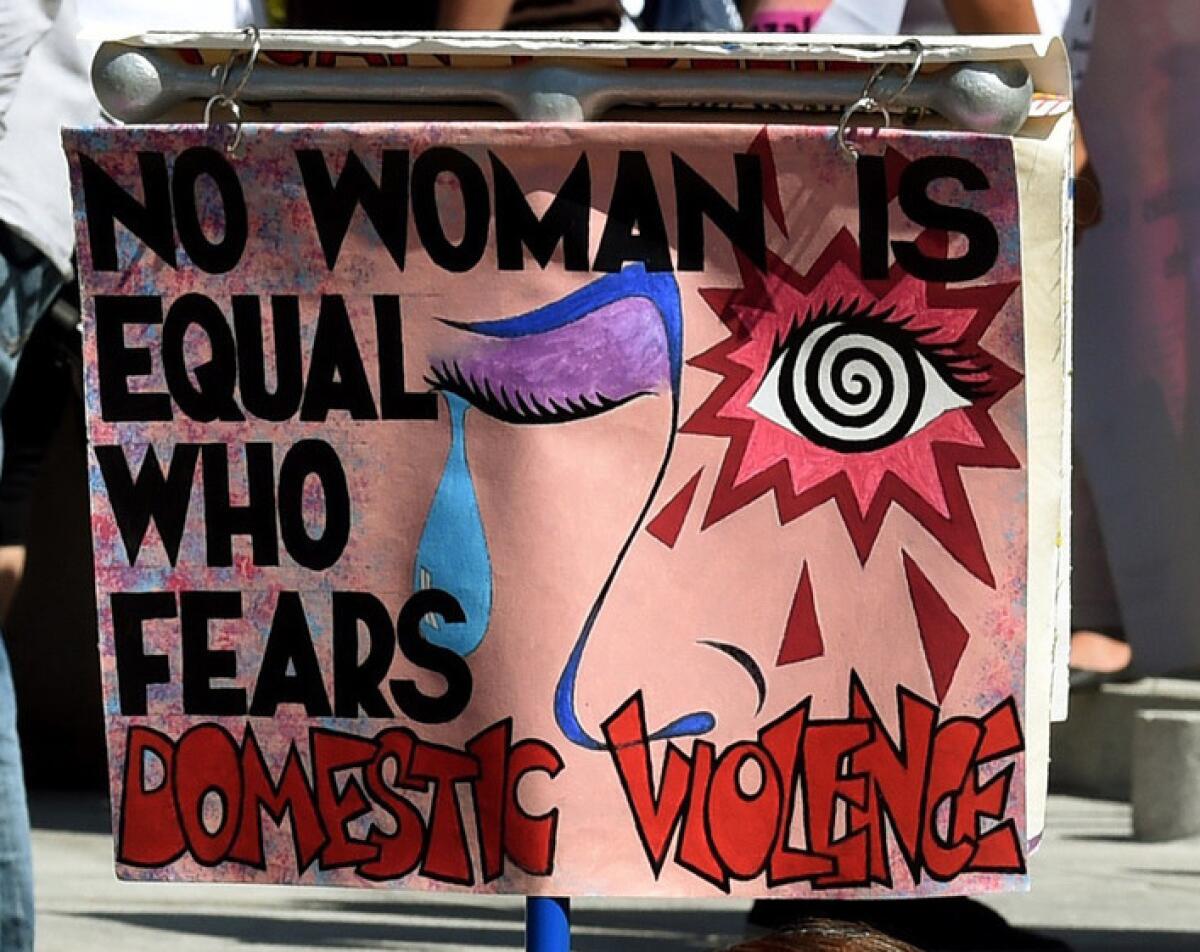

Domestic violence is rising during the pandemic. Here’s how to get help

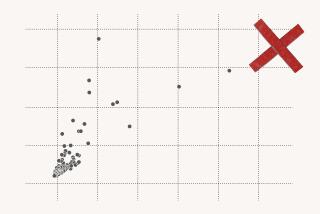

Calls to Los Angeles County’s domestic violence hotline have risen during the pandemic. And the Los Angeles Police Department has seen an increase in domestic violence calls for service.

As the pandemic continues, people should know that there are resources available for anyone experiencing abuse.

Organizations that help survivors are concerned that people who need help won’t seek it, either because they’re constantly at home with their abuser or they’re too scared to reach out.

“There are places to go,” City Atty. Mike Feuer told The Times. “There are resources on which you can draw.”

But what actually happens once you call a hotline or the police? To find out, I spoke with lawyers, city officials, service providers and police about the resources available to domestic violence survivors.

How do hotlines work?

The Los Angeles County Domestic Violence hotline is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. You can call if you need help or if you know someone who does. When you call the hotline, you will be prompted to enter your ZIP code and will be connected to a local service provider.

Resources

Phone numbers and websites for domestic violence survivors

L.A. County Domestic Violence Hotline: (800) 978-3600

Los Angeles LGBT Center:

(323) 993-7649 or (562) 433-8595 in Long Beach

L.A. County Superior Court self-help line for temporary restraining order: (213) 830-0845

Project Safe Haven:

corona-virus.la/DVResources

In an emergency, call 911.

The hotline is available in Arabic, Armenian, Cantonese, English, Farsi, Japanese, Khmer, Korean, Mandarin, Spanish, Tagalog, Thai and Vietnamese.

The providers can help you access counseling and legal services, formulate a safety plan, connect to a shelter or get a referral for medical services.

Eve Sheedy, the director of the L.A. County Domestic Violence Council, said the hotline can help you access services regardless of whether you plan to leave an abusive relationship.

“It doesn’t have to be a major decision just to reach out,” she said during a meeting with providers last month.

The hotline can also be a resource for friends and neighbors of survivors who want to figure out the best way to help their loved one.

The Los Angeles LGBT Center also offers domestic violence services for LGBTQ people.

What happens if I call 911?

Whether you make a phone call or send a text message to 911 (911 texting is available only in English), a specialized domestic violence police unit or a police patrol car — depending on availability — will come to your home.

“We get there, we make sure at the moment everyone is safe, separate parties and ask what happened,” said LAPD Det. Marie Sadanaga with the department’s domestic violence unit.

If a crime has occurred, police will make a report and will take temporary custody of any guns at the scene. If a crime has not occurred — for example, one person threw objects at a wall — police can document what happened and complete a domestic violence incident report. The report, mandated by the state, can be used in the future if the abuse continues, Sadanaga said.

If a specialized domestic violence unit comes to your home, an advocate will connect you to domestic violence resources or services such as shelter and safety planning. If a patrol officer responds, he or she should also be able to connect you with resources.

If you don’t want a patrol officer to come to your house, Sadanaga said that some LAPD stations allow people to make an appointment with an officer.

How do I get a protective order?

A protective order is a ruling by the court that will prohibit an assailant from having contact with you and your children.

The quickest type of restraining order — an emergency protective order — can be issued on the spot at the request of a police officer. An officer can call an on-duty judge at any time.

Before the pandemic, these orders lasted five business days or seven calendar days. Now an order can be given for up to 30 days to allow people more time to get to court to file for an order that will last longer.

It’s important to tell the officer about any specific limitations (child care or transportation issues) that would prohibit you from going to court in that timeframe.

The emergency order is a measure of protection until you can go to court to obtain a temporary restraining order, which is usually issued for 21 days but can be extended to 90 days.

To get a temporary restraining order, you can contact the L.A. County Superior Court self-help line, legal aid services or a private attorney.

The court allows people to file parts of these orders via email. Although the court clerk’s office reopened on June 15, you should make an appointment through the self-help line before actually going to court.

At the end of the order, there will be a hearing with a judge. The judge will either deny the restraining order, grant a permanent restraining order or move the hearing to a later date.

Separately, if criminal charges are brought against the assailant, a judge may issue what is called a criminal protective order. The detective investigating your case should be able to tell you about future hearings.

If an order is issued, keep a copy with you at all times.

Because of the pandemic, the Stanley Mosk Courthouse in downtown Los Angeles has been conducting remote hearings, said Michael Waldren, an attorney with Community Legal Aid of Southern California. That’s why Waldren recommends that clients try to file their cases there.

Julianna Lee, a supervising attorney at the Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles, said survivors should try to save any documentation of abuse such as text messages or photographs.

“Any documentation of the abuse is always helpful for a legal case,” she said.

What if I need shelter?

Because of the pandemic, the city and county have worked with local providers to nearly double the shelter capacity for domestic violence survivors and their families across Los Angeles County, an initiative called Project Safe Haven, according to the mayor’s office.

Through donors, the county can now accommodate an additional 900 families, up from 1,000 available beds.

City officials said that no one will ask about your immigration status. Transportation is also available.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.