Coronavirus Today: How L.A.’s sprawl fueled COVID deaths

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, Nov. 1. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

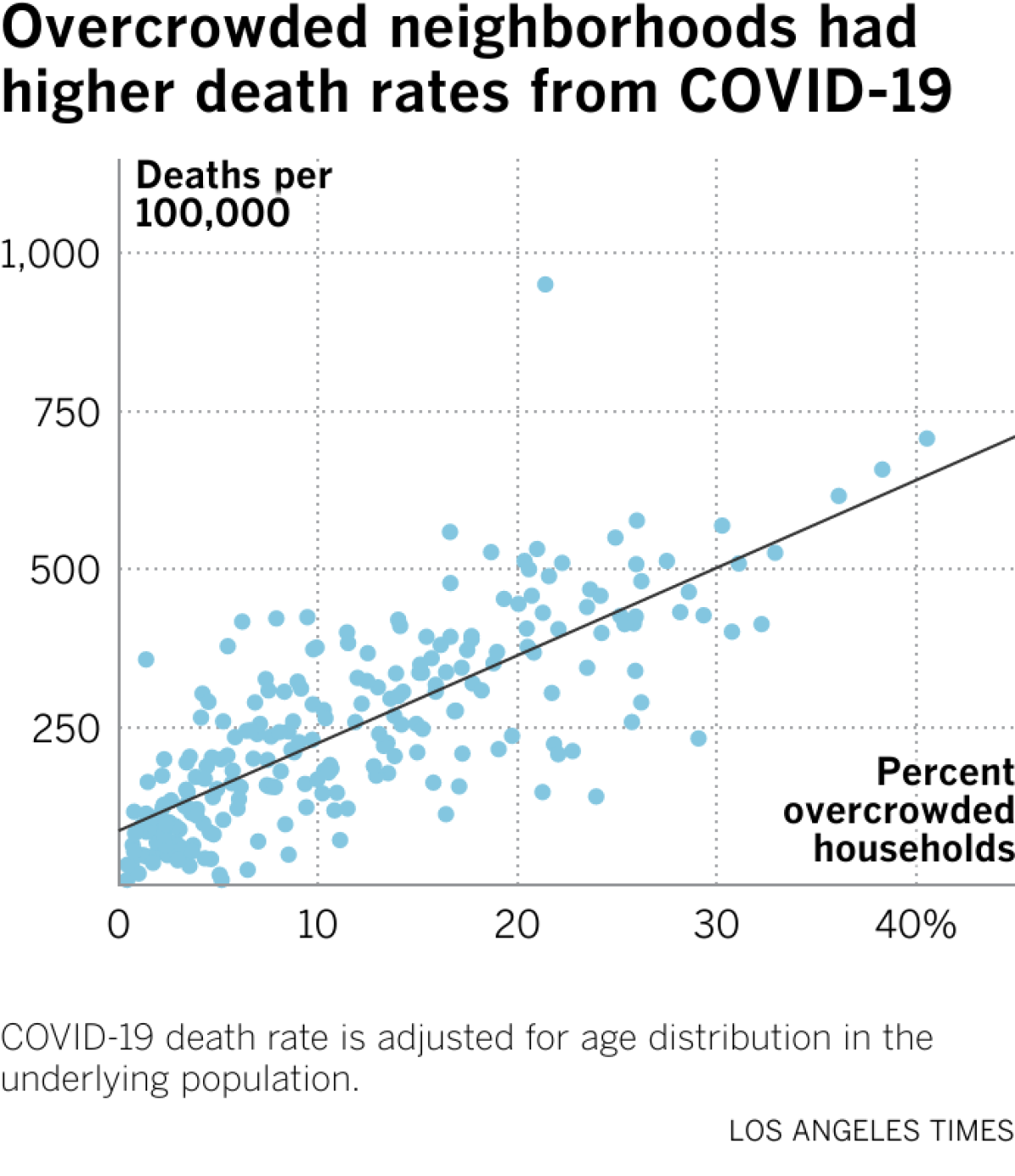

Take a close look at the graph below:

The X axis across the bottom indicates the percentage of households in a particular neighborhood that are overcrowded, meaning they house more than one person per room (excluding bathrooms). The Y axis along the left side measures the number of COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 residents.

Each blue dot on the graph represents a neighborhood in Los Angeles County. When you put them altogether like this, it’s pretty easy to see that neighborhoods with more overcrowding also tend to have the highest COVID-19 death rates.

That dot on the upper right is for Pico-Union, a neighborhood just across the 110 Freeway from downtown L.A. Its 1.33 square miles are home to about 40,000 residents, resulting in a population density that’s higher than New York City’s. The Big Apple manages to pack in millions of people by building upward. In skyscraper-free Pico-Union, they do it by cramming people into houses and apartments.

The result is that 40% of households in Pico-Union are overcrowded. For the sake of comparison, the national average is 3%.

Having so many people in such tight quarters has had deadly consequences for the people who live there. The neighborhood’s COVID-19 mortality rate — 825 per 100,000 residents — is the second highest in the county. (The top spot belongs to Little Armenia, where there have been 1,172 deaths per 100,000 residents.)

Social distancing sounds like something anyone can do for free. But in overcrowded places, it’s a luxury not everyone can afford.

Consider what happened in one Pico-Union residence: Leonardo Miranda, a 62-year-old construction worker, contracted the coronavirus in December 2020. He lived in a shed on the property but shared the bathroom, kitchen and dining room of the main house, where he spread the virus to a tenant who slept in the laundry room. From there it jumped to 67-year-old Yelman Oviedo and his 18-year-old grandson, who shared another room. Miranda and Oviedo died of COVID-19 15 days apart.

The story is tragic on its face, but there’s another layer that makes it worse: Los Angeles County’s overcrowding problem is the result of deliberate actions by civic leaders leaders going back more than a century, my colleagues Brittny Mejia, Liam Dillon, Gabrielle LaMarr LeMee and Sandhya Kambhampati report.

Creating a sprawling oasis of single-family homes meant not building apartments, high-rises or public housing complexes. Any of those would have improved living conditions for the region’s poorest residents. Instead, they had to squeeze themselves into the existing housing stock.

L.A.’s story begins after the Civil War, when it was billed as an alternative to the congested cities of the East. Those willing to venture west would be rewarded with single-family homes complete with lush lawns, gardens and fruit trees. But they would have to be white, according to real estate rules; the only option for people of Mexican heritage was to live in cramped shacks (where tuberculosis spread the way COVID-19 does now).

Fast-forward to the mid-1900s, when Mexican neighborhoods in Chavez Ravine were razed to make way for a public housing project that never got built, displacing thousands of residents. Other nonwhite neighborhoods were labeled slums and cleared away to build freeways and other projects. One such undertaking in Boyle Heights drove an estimated 10,000 people from their homes.

In the 1970s, the “slow growth” movement placed another hurdle in front of those who would have benefitted from high-density housing projects. “This change happened just as Mexican, Guatemalan and Salvadoran immigrants were pouring into the region to work, leaving them no choice but to pack into low-rise slums and hastily converted garages,” my colleagues write.

Since then, soaring housing costs have forced poor residents to double or triple up — or worse — to avoid the even worse fate of becoming homeless.

The story makes clear that unfair (to put it mildly) decisions made decades ago still have consequences today. Manhattan Beach is about the same size as Pico-Union, but in that wealthy (and mostly white) community, only 1% of households are overcrowded — and the risk of dying of COVID-19 is 11 times lower.

Please take the time to read the full story.

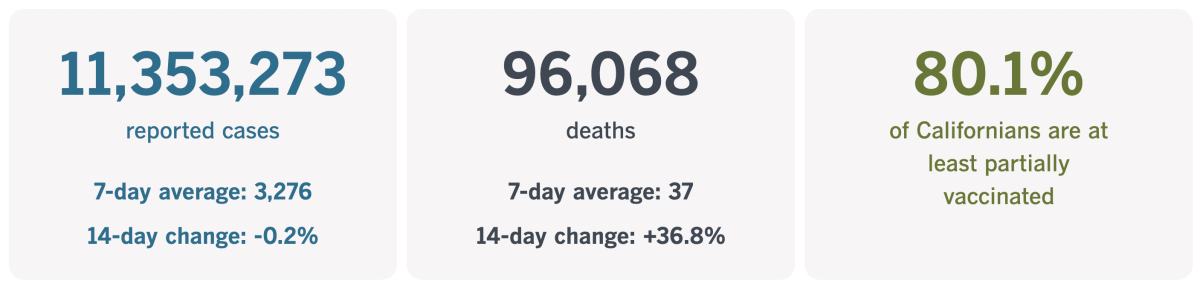

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 4:55 p.m. Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

COVID-19 vaccine house calls

The people who need COVID-19 vaccines the most are the people who face the greatest risk of becoming severely ill or dying if the coronavirus catches up to them. Chief among them are senior citizens and those with chronic health conditions.

Unfortunately, the factors that make them vulnerable may also complicate their ability to get to a doctor’s office, pharmacy or vaccination clinic to get the shots they need.

Luckily for them, there are people like Angela Tapia.

Tapia is a licensed vocational nurse, one of seven or eight the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health dispatches each day to vaccinate people in their homes. Altogether, the health department has about 28 people on its homebound vaccination team.

More than 7,400 county residents have gotten shots from Tapia and her colleagues, including more than 800 who’ve received an Omicron-targeting booster.

Among them was 88-year-old Maria Salazar, who is bedridden with Parkinson’s disease. My colleague Emily Alpert Reyes visited her home in Glassell Park when Tapia came to deliver a booster.

“I’m going to vaccinate you now, OK?” Tapia asked Salazar as her son, Louis, rubbed her foot.

Tapia also administered shots to Louis and his 90-year-old father while she was there.

“It’s a godsend,” Louis said, “especially for seniors that are homebound.”

In fact, the only bad thing anyone had to say to Alpert Reyes about the program was that it wasn’t reaching more people.

“Not one of my patients had ever heard of the in-home vaccination program from L.A. County. Not one,” said Dr. Gene Dorio, a house call physician in Santa Clarita who specializes in geriatrics. “If they had not heard it from me, they would never have known. My concern is, how many more people don’t know about the program?”

County officials estimate that more than half a million people here could be homebound. If so, the 7,400 who’ve been served so far would represent perhaps 1.5% of the folks who need vaccines brought to them.

Dr. Janina Lord Morrison, who serves as medical director of the mobile vaccine team, said the program was being promoted by doctors including Dorio, as well as through networks that serve seniors and on social media. But there’s still quite an awareness gap.

“The problem is that people just don’t know about this,” said Ernie Powell, president of Social Security Works California, an advocacy group.

The sooner that can change, the better. L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said the number of county residents who’d received one of the new COVID-19 booster shots needed to “increase pretty dramatically before we get into the holiday season.” If it doesn’t, she said, the consequences will be felt most by “older people, people with underlying health conditions. This will make a difference in their lives.”

For her part, Morrison said her team would keep on visiting county residents to deliver vaccines, be they bivalent boosters or a very first COVID-19 shot. (Flu shots are available as well.) People can request a visit from Tapia or one of her colleagues by calling (833) 540-0473 or filling out an online form.

“We’ll keep going as long as people are asking [for] us,” Morrison said.

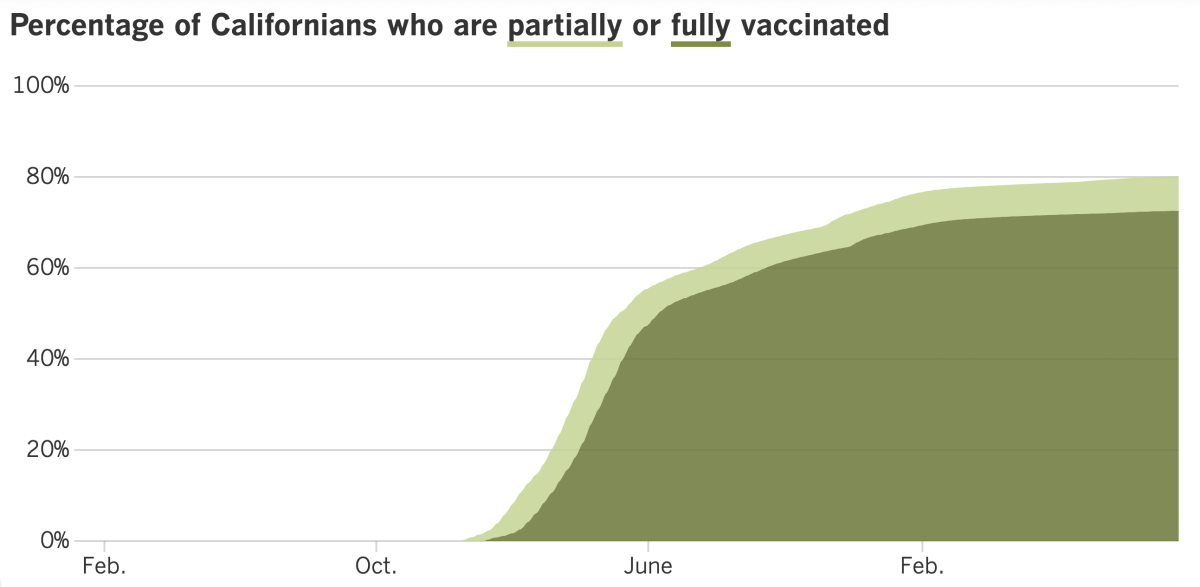

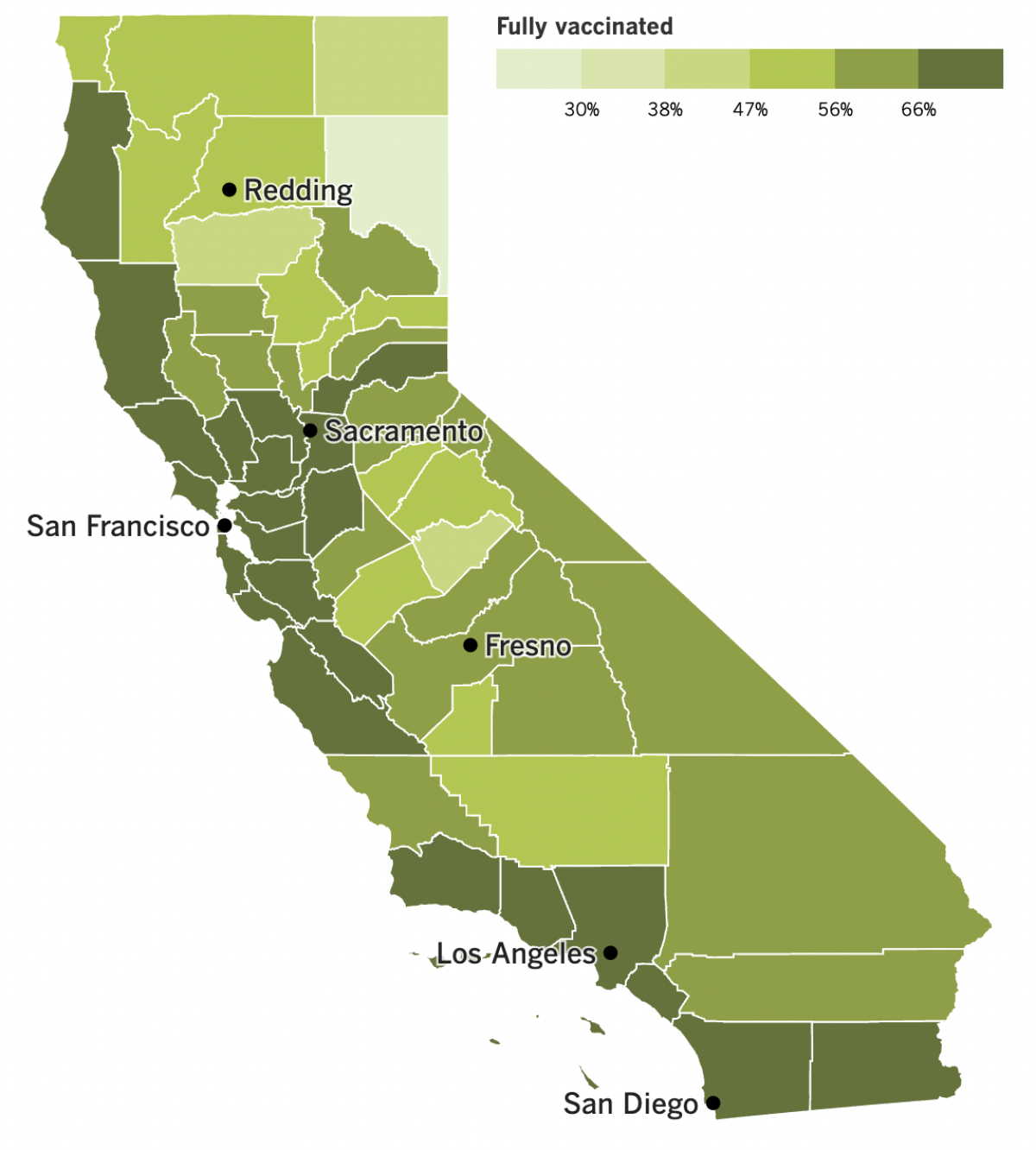

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

It looks like the era of BA.5 — the Omicron subvariant so menacing that the FDA ordered up fresh COVID-19 vaccines to thwart it — may be winding down.

For the first time in months, BA.5 accounted for fewer than half of the coronavirus specimens circulating in the U.S., according to estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. With a 49.6% share, however, it’s still more common than any other coronavirus strain.

But the strains in the No. 2 and No. 3 spots are steadily ascending. Over the last month, BQ.1’s presence has increased from 1.2% to 14% of U.S. specimens, and BQ.1.1’s rose from 0.5% to 13.1%. Both upstarts are subvariants of BA.5, and they may have acquired enough changes to overcome some of the immune protection provided by the new bivalent booster shots or by past infections with BA.5.

A statement issued last week by the World Health Organization’s Technical Advisory Group on SARS-CoV-2 Virus Evolution said that BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 have demonstrated “a significant growth advantage” over other subvariants, and not just in the U.S. In all likelihood, their success is due in part to “an immune escape advantage,” the group said. There’s no human data to confirm this — not yet, at least — but if that turns out to be the case, it would increase the odds of another COVID-19 surge.

It wouldn’t be the first time, Ferrer said. “Emerging variants and subvariants of the virus have played a large role in driving past surges,” she said, adding that “we ought to prepare for the possibility of another winter surge.”

The WHO technical group noted that there’s currently no sign either BQ.1 or BQ.1.1 increases the risk of severe illness, or that existing COVID-19 vaccines would be any less effective at preventing severe disease.

The threat of another surge isn’t exactly lighting a fire under Americans to get the new booster shots. At the CDC’s last count, fewer than 23 million Americans have received one. That’s only about 10% of those who are fully vaccinated (a number that’s stuck at 68.4% of the U.S. population).

Demand for the shots increases with age. The CDC says 7.3% of Americans 5 and older have had a bivalent booster. Among adults, that figure rises slightly to 8.6%. Even among senior citizens — who are most likely to become severely ill if infected — just 20.1% have rolled up their sleeves.

President Biden joined their ranks last week, getting his updated booster in front of cameras as members of his administration’s COVID-19 response team looked on. Biden didn’t get his shot when it first came out because he came down with COVID-19 this summer and opted to wait a few months to boost his immunity, as the CDC recommends.

He called on “all Americans to get their shot, just as soon as they can” and said most people live within five miles of a place where they can get the booster for free.

Speaking of vaccines, authorities in Shanghai have started offering one that can be inhaled as a mist rather than injected by a syringe. It’s believed to be the first such COVID-19 vaccine available to members of the general public.

In a video from a Chinese state media outlet, a man inhaled the vaccine and held his breath for five seconds. The entire procedure lasted no more than 20 seconds.

“It was like drinking a cup of milk tea,” a recipient said in the video. “When I breathed it in, it tasted a bit sweet.”

Elsewhere in China, workers walked out of a Foxconn plant where iPhones are assembled because they feared the company wasn’t keeping them safe from COVID-19. Up to half of the factory’s 200,000 employees have left the plant in the city of Zhengzhou, according to social media reports.

One employee told reporters that workers who fell ill did not receive medical treatment. A new mask mandate was implemented, but aside from that, work at the plant continues pretty much as before.

“There are still people getting infected at the assembly lines, and they are still worried about going to work,” said a worker who left the factory and planned to return to his hometown.

Lockdowns are back in place in Shanghai, where 1.3 million residents of a downtown district were ordered to get fresh coronavirus tests and remain in their homes until the results came back. The order came down on Friday, a day when Shanghai — a city of 25 million people — reported 11 new infections, none of them symptomatic.

To some, it was reminiscent of the beginning of the two-month lockdown that spread to the entire city earlier this year. Authorities initially said that episode would last just a few days, but it wound up dragging on so long that residents had to contend with food shortages.

The anti-COVID measures extended to Shanghai Disneyland, which temporary closed Monday night — with visitors still inside — so both staffers and guests could be given expedited coronavirus tests, according to the city government. No details about a possible outbreak at the theme park were released.

Reports on social media said some of the rides and other amusements remained open to entertain visitors until it was their turn to be tested.

“Please return and take a tour in the park,” a masked employee told guests in a video posted on the Sina Weibo platform. “The park’s gates are all closed temporarily, and you cannot leave now.”

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Have the main symptoms of COVID-19 changed?

You may be wondering this if you heard about a report from the Zoe Health Study, which uses an app to collect health information from legions of volunteers. In October, the researchers who run the study — a group from Harvard, Stanford and King’s College in London — shared an update that revealed two interesting things about COVID-19.

First, the most frequently reported symptoms have indeed shifted. Compared with earlier periods of the pandemic, people who get sick now are more likely to experience symptoms that are normally associated with colds, the flu and allergies.

Sneezing, for instance, has become a very common symptom. That tracks with the fact that Omicron infections tend to cause upper-respiratory symptoms, while earlier strains were more likely to produce lower-respiratory illnesses, such as pneumonia.

Also gone from the top of the list are symptoms like muscle pain, chills and loss of taste or smell.

The second interesting thing is that the top five symptoms varied a bit according to vaccination status. With that in mind, here are three separate lists of the new most-common COVID-19 symptoms, starting with people who are fully vaccinated:

1. Sore throat

2. Runny nose

3. Blocked nose

4. Persistent cough

5. Headache

For those who are unvaccinated, the symptoms are:

1. Headache

2. Sore throat

3. Runny nose

4. Fever

5. Persistent cough

And for those who’ve had just one initial dose of vaccine, they are:

1. Headache

2. Runny nose

3. Sore throat

4. Sneezing

5. Persistent cough

These particular lists are based on reports from COVID-19 sufferers in the United Kingdom, where new cases have been rising.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

The device in the photo above is a pulse oximeter. These gadgets clip on to a person’s finger and measure the amount of oxygen in their blood. They used to be found mainly in hospitals, but the pandemic brought them into homes as well.

A pulse oximeter works by sending two wavelengths of light into the skin, then measuring how much of that light is absorbed. Those measurements make it possible to gauge how much oxygen the blood contains. But there’s a problem: The devices don’t account for light-absorbing properties of melanin, the pigment responsible for skin tone.

As a result, pulse oximeter readings for people with darker skin may not be reliable. One study found that hospitalized Black patients were nearly three times more likely than their white counterparts to have normal readings on pulse oximeters even when their actual oxygen levels were dangerously low.

Recent studies have documented the negative consequences for patients of color, and now the Food and Drug Administration is taking a closer look. The agency gathered a panel of experts Tuesday to discuss what could be done to alleviate this racial disparity and make sure the devices are safe for everyone.

“The fact that such a commonly used device could have any discrepancy at all was shocking to me,” said Dr. Michael Sjoding, a University of Michigan pulmonologist who led the study of hospitalized patients. “I make a lot of medical decisions based on this device.”

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in various ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, as well as resources for people experiencing domestic abuse.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.