Coronavirus Today: Who’s dying of COVID-19 now?

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, Sept. 20. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

“People aren’t dying of COVID anymore.”

It may seem that way, especially when President Biden disses masks on “60 Minutes” and tells a national TV audience that “the pandemic is over.”

But when a friend made that observation to Erick Morales recently, he begged to differ.

Morales’ own mother, Alejandra Gutiérrez, died of COVID-19 in June at the age of 59.

Gutiérrez was vaccinated and boosted. She was careful, and so were her adult children, who wore masks when they were with her and avoided social situations that might result in a coronavirus exposure.

But Gutiérrez was unlucky. She came down with ovarian cancer during the first pandemic winter, and despite multiple treatments, it spread to her brain in January.

The cancer weakened her, but it wasn’t what killed her. She caught COVID-19 in late May and struggled to breathe. In her final days, she lost the ability to speak.

Gutiérrez was one of the more than 400 people who died of COVID-19 each day in the U.S. during June, July and August, according to data from the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Even now, with the second Omicron wave ebbing, COVID-19 is still killing an average of 425 Americans per day, the center reports.

In January 2021, when the first COVID-19 vaccines were being rolled out, the country’s daily death toll exceeded 3,300. A number like 425 is a definite improvement. But it’s a lot higher than the handful of cases many of us presume it to be.

For the record:

10:41 p.m. Sept. 21, 2022A previous version of this newsletter said that in January 2021, the country’s daily COVID-19 death toll exceeded 23,000. That was the weekly death toll, which averaged out to more than 3,300 deaths per day.

In fact, COVID-19 is still one of the country’s leading causes of death. As of Tuesday, it would rank fifth, between strokes (439 deaths per day) and chronic lower respiratory diseases (418 deaths per day).

If that seems hard to believe, how about this: In Los Angeles County alone, nearly 800 people died of COVID-19 between May and July. That’s roughly 60% higher than during the same three months last year, when the county recorded nearly 500 deaths.

At a time when vaccines, boosters, medications and antibody treatments are plentiful, when hospitals have the bandwidth to care for patients who are seriously ill, and when, as White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator Dr. Ashish Jha said, “most COVID-19 deaths are preventable,” you’ve got to wonder: Who is dying of COVID-19 now?

My colleagues Emily Alpert Reyes and Aida Ylanan have the answer.

It turns out that Gutiérrez was a something of an anomaly. Recent COVID-19 deaths have been heavily concentrated among senior citizens.

In California, about half of those who died this summer were at least 80 years old. Another third were people between the ages of 65 and 79.

Throughout California, Black residents had the highest COVID-19 death rate, pretty much regardless of age. And in L.A. County, men have been more likely to die than women.

Gutiérrez was a typical COVID-19 victim in one respect: She already had a health problem that made her vulnerable to a serious case of COVID-19. For people like her, an encounter with the coronavirus can be like dry brush encountering a lit match, said Michael T. Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota.

“It doesn’t cause the high temperatures, or the winds, or the low humidity,” he said. “But nothing happens until you throw that SARS-CoV-2 virus into the mix.”

Here in L.A. County, nearly half of the people who died of COVID-19 between May and July were contending with at least three health conditions before the coronavirus came along, and almost all had at least one. Those conditions weren’t necessarily as serious as ovarian cancer; typical examples include obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease.

In addition, residents of poorer neighborhoods were more likely to die of COVID-19 than residents of wealthier ones.

But COVID-19 can kill anyone. In recent months, hundreds of young and middle-aged adults have died of the disease, as have four minors. And so have 412 Californians over the age of 12 who were vaccinated (including 260 who were also boosted), although they represent less than 0.01% of state residents who’ve gotten the shots.

The Omicron variant — especially the BA.5 subvariant — has been infecting so many people that you’ve surely encountered tons of people who’ve recently recovered from a bout with COVID-19. More than in years past, it probably feels like COVID-19 survivors are everywhere. And they are.

But the number of infections is so high that even with a low mortality rate, the death count is still substantial. It’s just that in a country eager to move on from the pandemic and stop thinking about things such as masks and booster shots, these deaths aren’t getting the attention they deserve.

“The elderly, the immunocompromised, and the unvaccinated or under-vaccinated — they are the ones that account for the vast majority of deaths due to COVID-19,” said Dr. Thomas Yadegar, medical director of the intensive care unit at Providence Cedars-Sinai Tarzana Medical Center.

“We’ve sacrificed the lives of our most vulnerable for our own convenience,” he said.

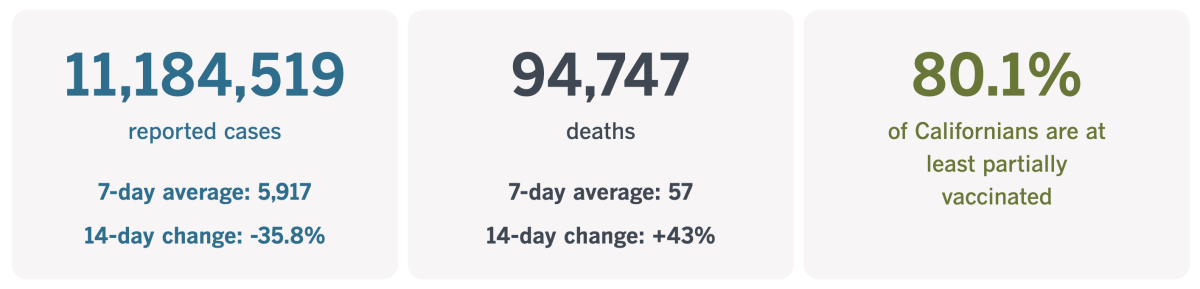

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 4:55 p.m. on Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

How to prevent the next pandemic

It’s no secret that the United States had a less-than-textbook response to the COVID-19 pandemic. It turns out we had plenty of company, even among wealthy nations that were expected to be more prepared.

So says a group of experts convened by the medical journal Lancet. In a report released last week, they made it abundantly clear that they were not impressed with the world’s efforts to rise to the occasion.

The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation estimates the pandemic’s global death toll at around 17.2 million, a “staggering” figure that is “both a profound tragedy and a massive global failure at multiple levels,” the members of the Lancet COVID-19 Commission wrote.

And there’s plenty of blame to go around, they added: “Too many governments have failed to adhere to basic norms of institutional rationality and transparency, too many people — often influenced by misinformation — have disrespected and protested against basic public health precautions, and the world’s major powers have failed to collaborate to control the pandemic.”

That failure to collaborate came in many forms, the commission members wrote. It started with China’s delay in notifying the world about the patients in Wuhan who had come down with a mysterious type of pneumonia that wasn’t caused by any known virus. It continued with multiple countries’ failure to coordinate their efforts to contain and suppress the novel virus, or to figure out what those efforts ought to entail.

Wealthy countries didn’t do enough to ensure that low- and middle-income countries had the money they needed to procure personal protective equipment, ventilators, test kits and other necessary supplies. And when there were limited supplies of medicines and vaccines, rich nations did not share equally with poor ones, the report says.

Countries did not gather “timely, accurate, and systematic data on infections, deaths, viral variants” and other factors that would be important to know if you wanted to get a pandemic under control, the experts wrote.

The World Health Organization didn’t want to get ahead of the science — with good reason — but it took too long to acknowledge that people with asymptomatic infections could spread the coronavirus without realizing it, and that the virus spreads mainly through the air. As a result, the WHO was “slow to advocate policy responses commensurate with the actual dangers of the virus,” the report says.

And no one at any level has had much success combating the “extensive misinformation and disinformation campaigns on social media,” the report adds.

That’s not even a complete list of the problems the Lancet commission identified.

The commission was established in July 2020 with the aim of finding ways to help countries work together more effectively. Its 28 members are experts in disciplines such as epidemiology, vaccinology, economics and public policy.

Right off the bat, the report explains that you can’t suppress an infectious disease without “prosociality,” which means prioritizing the good of society as a whole over the interests of individuals. Unfortunately, the growing gap between the “haves” and “have-nots” in many countries has undermined any sense of collective purpose.

In the United States and elsewhere, false claims about COVID-19 vaccines and debunked treatments such as ivermectin, among other things, were spread by politicians and cable television personalities for the sake of partisanship, not public health. In the U.S. alone, unfounded anti-vaccine sentiment has led to as many as 200,000 preventable deaths, and “this anti-science movement has globalised with tragic consequences,” the commission wrote.

We can’t go back in time and do everything over. But the commission offered advice on where to go from here.

For starters, it said it’s not too late for countries to get serious about the basics, including mass vaccination, accessible testing, and treatment. They should be accompanied by policies that support people who need to isolate, as well as common-sense preventive measures such as mask mandates in certain settings. Most importantly, the commission wrote, these efforts “should be implemented on a sustainable basis, rather than as a reactive policy that is abruptly turned on and off.”

To make sure the pandemic ends as quickly as possible, countries should work together to track new coronavirus variants and quickly assess the risks they pose.

To be better prepared for the next pandemic threat, the commission advised countries to strengthen their own health systems and make sure everyone has access to medical care. In addition, they should shore up their disease surveillance and reporting systems, emphasize the importance of preventive health and emergency preparedness, improve their public health communication strategies, and more aggressively fight health disinformation, according to the report.

Countries should invest a lot more in the World Health Organization and come up with better ways to cooperate and coordinate — and they should do it now so they’ll be ready when the next infectious disease threat inevitably arises.

That said, countries need to work harder to prevent that next outbreak from happening, the commission said. That means they should come up with more uniform rules about the trade of both domestic and wild animals, and make sure they’re enforced. They should also give the WHO more authority to keep tabs on research programs involving dangerous pathogens to make sure that biosafety rules are followed.

Whether anyone will follow this advice remains to be seen. The commission didn’t exactly strike an optimistic tone as it wrapped up its report:

“The lack of ambition in the global response to COVID-19 is like that of other pressing global challenges, such as the climate emergency; the loss of global biodiversity; the pollution of air, land, and water; the persistence of extreme poverty in the midst of plenty; and the large-scale displacement of people as a result of conflicts, poverty, and environmental stress.”

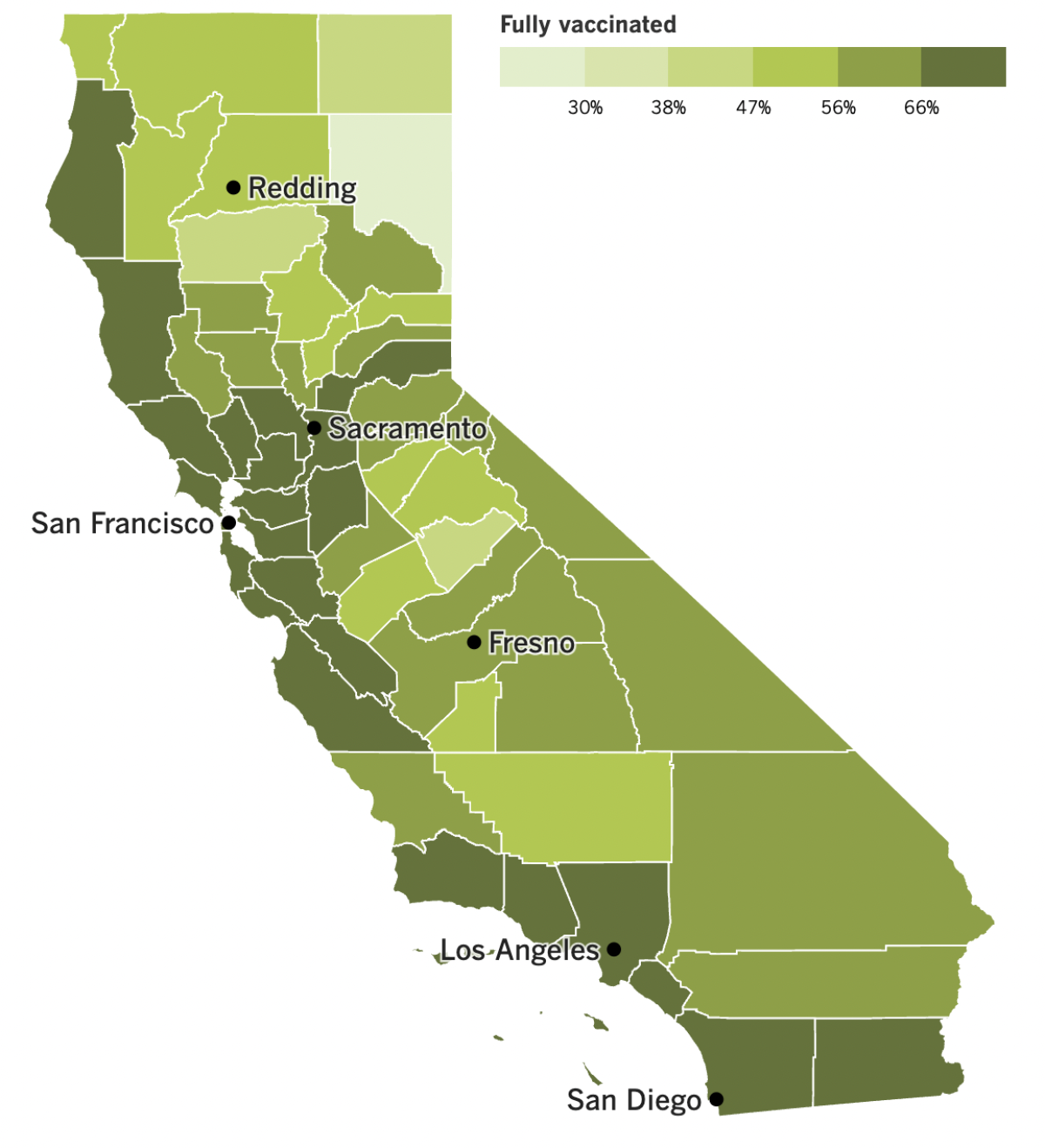

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

Another pandemic precaution has bit the dust: As of Saturday, California no longer requires unvaccinated workers at healthcare facilities, schools and other congregate settings to get tested for coronavirus infections once a week.

Those weekly surveillance tests used to be an important part of the state’s pandemic response. But considering where we are in the outbreak, the tests aren’t nearly as useful as they once were.

Most state residents now have some immunity through vaccination or a past infection — or both — so they face less risk of becoming seriously ill. Plus, the Omicron subvariants spread so quickly that weekly testing isn’t enough to slow it down, said Dr. Tomás Aragón, director of the California Department of Public Health.

Los Angeles County may drop one of its rules by the end of the month if coronavirus case rates continue to decline. If the county sees fewer than 100 cases a week per 100,000 residents — roughly 1,400 cases per day — masks will no longer be required on public transportation or in hubs such as airports and train stations.

As of Tuesday, the county was averaging 1,735 cases per day over the last week, according to The Times’ tracker. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said we could hit the lower threshold by the end of the month.

Should that happen, the county would also stop recommending that everyone wear a mask indoors in public settings such as grocery stores and offices. Face coverings would still be strongly recommended in high-risk settings for people who are older, unvaccinated, live in high-poverty areas or have health conditions that make them more susceptible to a severe case of COVID-19. Otherwise, the decision about covering up would be a matter of personal preference.

Masks will continue to be required in healthcare settings, correctional facilities, cooling centers and a handful of other places.

California isn’t the only place seeing pandemic improvements. The World Health Organization says the number of new infections is dropping in every part of the globe.

The WHO’s latest weekly report counted 3.1 million new cases, a 28% drop from the previous week. Deaths also fell by 22%, to just over 11,000 — the lowest worldwide death toll since March 2020.

“We are not there yet, but the end is in sight,” WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said Wednesday.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the top infectious disease expert in the U.S., agreed Monday that “we’re heading in that direction.” But unlike Biden, he walked back Biden’s assessment that the pandemic phase of the outbreak was already behind us.

“It is likely that we will see another variant emerge” in the late fall or winter, Fauci said Monday during a talk at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

Dr. Eric Topol, a professor of molecular medicine at Scripps Research in La Jolla, schooled the president as well.

“We all wish that were true,” Topol wrote in an an op-ed. “But unfortunately, that is a fantasy right now. All the data tell us the virus is not contained. Far too many people are dying and suffering. And new, worrisome variants are on the horizon.”

An experimental vaccine may help us stay ahead of those new variants. Instead of focusing solely on the spike protein, which has proved adept at mutating in ways that reduce vaccine effectiveness, the new shots also target a far more stable nucleocapsid protein.

Although the vaccine’s design was based on an early coronavirus strain first seen in Wuhan, it was effective against both the Delta and Omicron variants and when tested in mice and hamsters. It’s still several steps away from being tested in humans, but scientists are optimistic that it could lead the way to a one-size-fits-all vaccine that provides lasting protection without needing to be tweaked on a regular basis like the flu shot.

“It’s a great idea,” said Dr. Paul Offit, a virologist and immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania who wasn’t involved in the research. “You could have argued that we should have done this at the beginning.”

And finally, the Chinese government is facing more complaints about its zero-COVID strategy. Earlier this month it was a magnitude 6.8 earthquake in Sichuan province that triggered protests because millions of residents in lockdown were prevented from fleeing their seriously damaged homes.

This week it was a fatal bus crash in the middle of the night in Guizhou province. Forty-seven passengers were being transported to a quarantine facility outside the capital city, Guiyang; 27 of them died.

Critics went online and accused the government of moving the passengers for political purposes, not public health ones. They speculated that residents were being taken outside the city limits so Guiyang wouldn’t have to report any new illnesses.

“Will this ever end?” one commenter asked. “Is there scientific validity to hauling people to quarantine, one car after another?”

In addition, residents in some neighborhoods complained of hunger after food deliveries were missed, a mistake local officials attributed to their “lack of experience and inappropriate methods.” The local zoo worried it would run out of food for its animals and appealed to the public for donations of pork, chicken, apples, watermelons, carrots and other produce.

Food shortages are also a problem in Ghulja, a city in China’s far western Xinjiang region where the Uyghur population is used to harsh treatment from the government.

After more than 40 days of lockdown, hungry and frustrated residents went online to share videos of empty refrigerators and feverish children. In some cases, people who have ingredients to make bread haven’t been able to bake their dough because authorities won’t let them go outside to use their backyard ovens.

Nyrola Elima, Uyghur from Ghulja who no longer lives there, told the Associated Press that her father was sharing one tomato each day with his 93-year-old mother, and that her aunt was desperate for milk for her toddler grandson. Her account could not be independently verified, but her descriptions were in line with videos posted by others.

Chinese censors worked to remove those posts from social media, though some reappeared. Six people were arrested for “spreading rumors” about the lockdown.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: What’s the difference between being “fully vaccinated” and being “up to date”?

The CDC considers someone to be “fully vaccinated” if they’ve finished their primary series of COVID-19 shots. For Comirnaty (the vaccine from Pfizer and BioNTech), Spikevax (the one from Moderna) and the (relatively) new offering from Novavax, that means two shots given between three and eight weeks apart. Only a single dose is required for the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

But immunity wanes and new variants spark fresh COVID-19 surges. That means being “fully vaccinated” is just the beginning.

The immune system needs a refresher course from time to time, and a booster shot provides one. But rather than change the definition of “fully vaccinated,” the CDC instead said people who got the boosters recommended for them were “up to date” with their vaccinations.

If you’re at least 12 years old, that means getting a new bivalent booster shot to (hopefully) bolster your protection against BA.4 and BA.5. To be eligible, you must be fully vaccinated and not have had a COVID-19 vaccine in at least two months or a coronavirus infection in at least three months. Once you get a bivalent booster, you’ll be considered “up to date” regardless of how many booster shots you’ve had (or missed) in the past.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

The woman at Hermosa Beach in the picture above is Sandhya Kambhampati, a colleague of mine on the Data Desk. She caught COVID-19 very early in the pandemic, then became one of the first long COVID patients her doctors had encountered. Last year, she wrote a first-person account of what it took to convince them her symptoms were real.

They finally came around, but Kambhampati still struggled. Eventually, at her doctors’ insistence, she took a leave from work so she could focus on healing. Painting became an integral part of that process.

“At first, it offered an escape on my worst days, but over the last few months, it has developed into much more,” she writes in a new essay. Painting sunsets at the beach is simultaneously calming and energizing, allowing her to recharge her batteries and help others who are just starting their journeys with long COVID.

“Painting gives me a place to release the medical trauma that people share with me and keep going,” she writes.

You may not be dealing with long COVID, but you can follow Kambhampati’s lead and shift your mind-set for the better.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in various ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, as well as resources for people experiencing domestic abuse.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.