Coronavirus Today: The COVID lies we all tell

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, Oct. 11. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

Tonight, the Los Angeles Dodgers kick off their postseason by hosting the San Diego Padres at Chavez Ravine. It’s their third World Series run since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

If you’re one of the roughly 56,000 lucky fans who scored a ticket to the game, would a runny nose keep you away from Dodger Stadium? What about a hacking cough? If you were feeling achy and a tad feverish, would you take a coronavirus test before setting out for Elysian Park, or would you rather not know you had a medical reason to stay home?

You don’t have to be a baseball fanatic to understand why it would be tempting to ignore official public health advice. Perhaps you let your conscience guide you nine times out of 10. But there are bound to be occasions — a wedding, a music festival, a long-awaited vacation — when you decide to proceed with your plans and hope for the best.

A new study says you’ve got lots of company.

Researchers surveyed 1,733 adults from around the country about their COVID-19 honesty and adherence to pandemic health guidelines and found widespread lapses on both counts. Altogether, 41.6% of the survey-takers admitted they’d taken at least one kind of deceitful action on at least one occasion, according to a report published Monday in the medical journal JAMA Network Open.

The most common lies involved telling people they were with, or were about to meet up with, that they’d taken more COVID-19 precautions than they actually had. Just under 1 in 4 of those surveyed copped to that.

Coming in a close second was failure to follow quarantine and isolation rules — 22.5% acknowledged doing that.

In addition, 21% of study participants said they decided not to take a coronavirus test when they thought they might have COVID-19, and 20.4% said they’d lied about their likelihood of being infected when answering screening questions to visit a medical office.

Other kinds of “misrepresentations” included when someone knew or strongly suspected they had COVID-19 but didn’t share that information with a companion; not answering truthfully when being screened to enter a public place; saying they didn’t need to quarantine or isolate when they actually did; and being dishonest about their vaccination status.

The survey didn’t ask people how often they’d veered from the straight and narrow when it came to pandemic precautions. But the fact that more than 4 in 10 were willing to say they’d done so at least once wasn’t completely surprising.

In nonpandemic times, people are known to withhold information they find embarrassing, would cause them to be judged, or would deprive them of some kind of advantage, the study authors noted. Folks are also reluctant to follow rules that ask them to do something difficult, such as spending less money to shore up their savings or skipping dessert for the sake of their health.

The researchers acknowledged that doing the right thing isn’t always easy. It’s not simply a matter of FOMO — sometimes, staying home while sick means putting your job at risk, or delaying time-sensitive medical care.

Indeed, 39.2% of those who lied about their need to isolate themselves from others said they did so because they couldn’t afford to miss work. Likewise, 32.3% of those who claimed to be vaccinated but weren’t said they misrepresented their status because they needed to work.

But there were also plenty of instances of people behaving badly, such as the 35.5% of people who failed to share that they probably or definitely had an active case of COVID-19 because they didn’t want the people they were with “to be angry at me for exposing them,” according to the study. In addition, 36.3% of people who concealed their COVID-19 status said they did so because they “didn’t want to miss an event or fun activity.”

Often, people substituted their own judgment for the advice of experts. That includes the 48.9% of people who broke isolation and quarantine rules because they “didn’t feel very sick.” It also includes the 32.3% who falsely claimed to be vaccinated because they “didn’t think it mattered.”

And some people said they set the truth aside out of principle, like the 50% of people who lied about being vaccinated because they “wanted to exercise my freedom to do what I want.” It also includes the 59.3% of people who broke isolation and quarantine rules because what they do is “no one else’s business.”

The most common excuse for lying was that people wanted their lives to feel “normal,” as if the pandemic had never happened. That was the reason offered by 57.7% of those who said they fibbed about their COVID-19 status in order to enter a public place, as well as 50% of those who misrepresented their vaccination status.

The younger survey-takers were, the more likely they were to be shady. Compared with adults 60 and older, those in their 50s were twice as likely to report at least one instance of fudging the facts or breaking the rules. The odds were three times higher for people in their 30s and five times higher for those ages 18 to 29.

The study authors, led by psychology professor Andrea Gurmankin Levy of Middlesex Community College in Middletown, Conn., said some COVID-19 liars may have lied when answering the survey questions. If so, the actual amount of dishonesty around COVID-19 would be higher than the figures reported here.

Either way, it doesn’t bode well for our collective ability to put this pandemic behind us in a timely manner.

“Public health measures have the potential to dramatically reduce the spread and impact of the disease,” Levy and her colleagues wrote, “but their success depends on the public’s willingness to be honest about and adherent to these measures.”

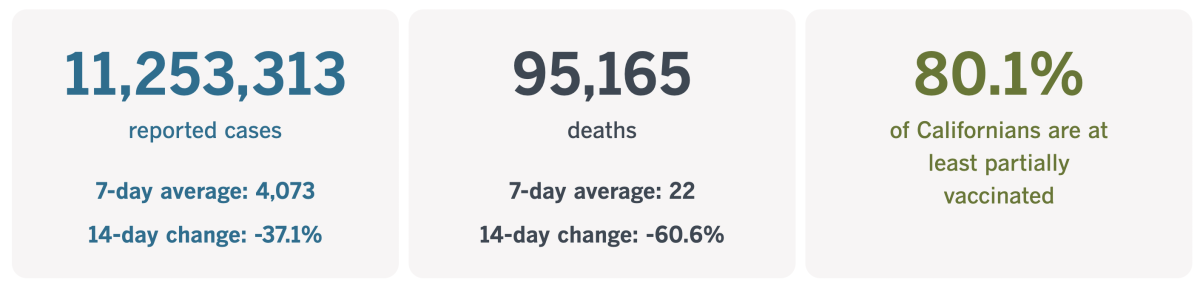

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 5:28 p.m. Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

What it’s like to live without a sense of smell

Nicole Kagan is a junior at Duke University, and she has no idea what her campus in Durham, N.C., smells like. She has never appreciated the sweet scent of the school’s magnolia trees or wrinkled her nose at the sweaty odor of Cameron Indoor Stadium.

Most important, when there was a gas leak in her dorm, it failed to register. Luckily, a resident

assistant came to her room and told her to evacuate.

Kagan’s life wasn’t always this way. She grew up with a fully functioning olfactory system, taking in the distinctive scents of bread baked in Subway sandwich shops, wet dogs, fresh soil and strawberry Jell-O, among others.

That all changed after she got COVID-19.

“I caught the virus early in the pandemic and had terrible symptoms, but after a week of bed rest, I was ready to resume my life,” Kagan, a recent summer intern, writes in The Times. “My nose wasn’t.”

Kagan tells us what it’s like to have anosmia, the medical term for losing one’s sense of smell. It used to be an obscure problem, but the coronavirus is making it almost commonplace.

Among those who lose their olfactory abilities during the acute phase of COVID-19, an estimated 5% remain unable to smell long after the rest of their body has recovered. There is no cure to get it back.

Not that Kagan hasn’t tried. She’s had a nasal endoscopy and tried a daily nasal steroid. She’s also tested various remedies touted on social media, including aromatherapy, eating a burned orange and a flick to the back of the head. None of them worked.

Of the five senses, you may not consider smell to be as crucial as sight or hearing. But it’s doing a lot of important work that we all take for granted — until it’s gone.

Without it, Kagan has no way to judge whether the food in her fridge is spoiled, or whether her body odor is scaring people away.

She has developed several hacks for getting by without the information her nose would normally feed her.

For instance, if she steps into new restaurant, she’ll ask, “What’s that smell?” If there is one, someone can describe it to her and she won’t have to feel left out.

“My close friends understand the need to say that bakeries we pass smell like caramelized sugar, and that college parties we attend smell like sweaty boys and old beer,” she writes. “Those are smells I know.”

Kagan spoke with Chrissi Kelly, who lost her sense of smell for eight years after suffering a sinus infection. At the time, anosmia was so uncommon that she created an organization called AbScent to assist those who have it and raise awareness among those who don’t. She has yet to find an easy way to describe what it’s like.

“You just don’t even know where to begin,” Kelly told Kagan. “I think it’s because smell is so elemental to all organisms. And therefore, imagining life without that is just unthinkable. It’s like saying, ‘OK, I’d like you to imagine a life without gravity. Or how about you imagine a life without time?’”

AbScent is a lot busier than it used to be. Since COVID-19 came along, the group’s membership has ballooned from 1,500 to more than 85,000.

Kagan would rather not count herself among the world’s anosmiacs. Sometimes she catches a whiff of dog food or cigarette smoke and thinks her sense of smell might be returning. Then she wonders whether they’re “phantom scents,” conjured by her brain as she fed her pet or passed a smoker on the street.

As long as she’s living in an essentially scent-free world, she’s trying to appreciate the limited upsides. Among them, she writes: “I can cook broccoli in my studio apartment and use public bathrooms without gagging.”

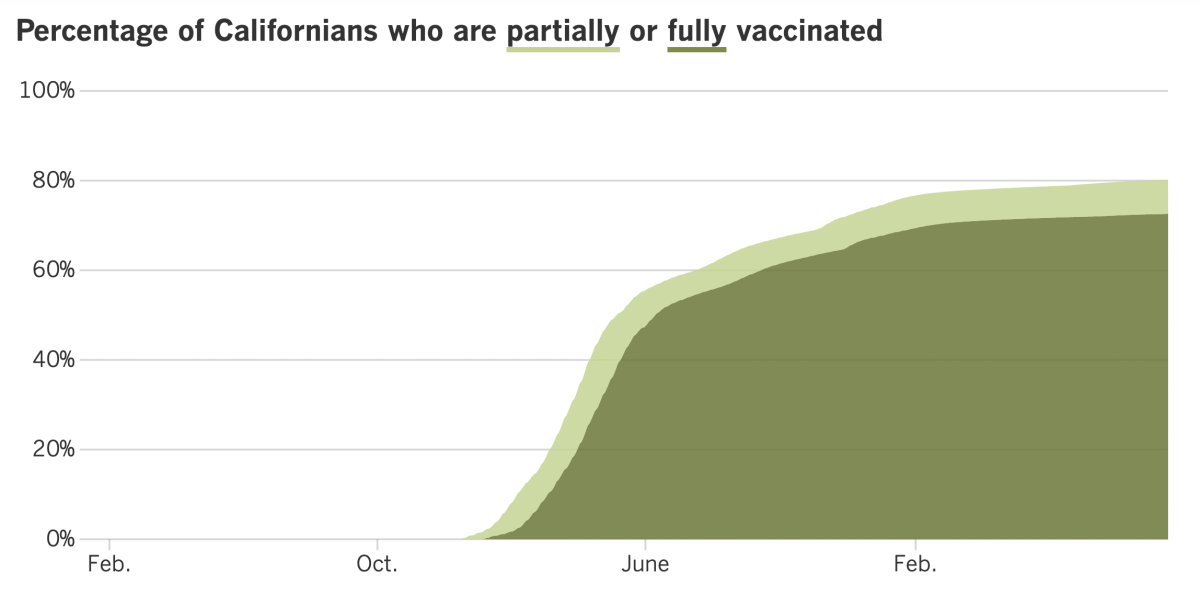

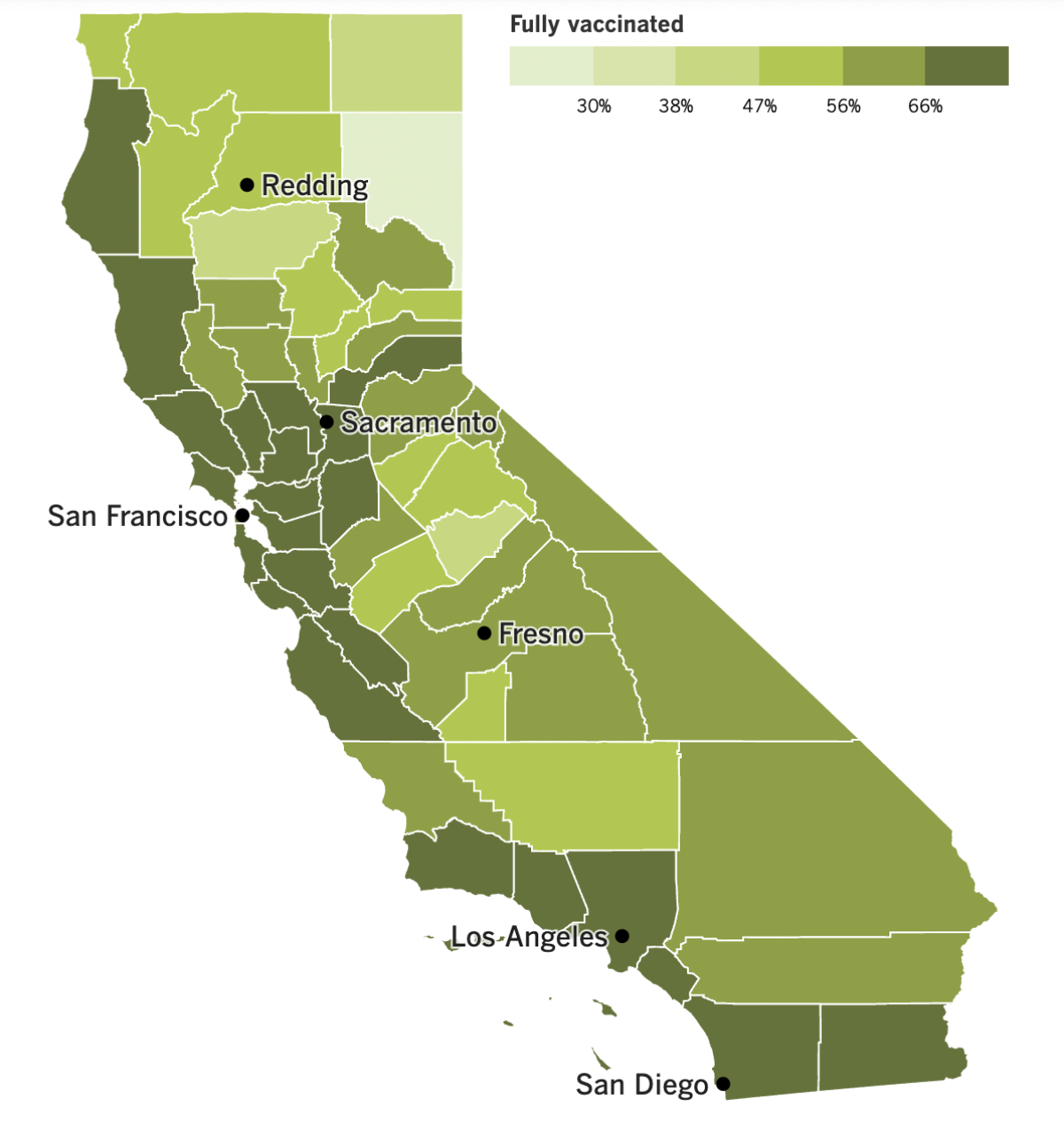

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

The Omicron subvariant known as BA.5 is still the big dog, accounting for an estimated 79.2% of coronavirus specimens circulating across the country. But scientists have their eyes on the upstart known as BA.2.75.2, and they’ve now spotted it in Los Angeles County.

Three BA.2.75.2 specimens were identified here last week, according to L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer. That has the potential to spell trouble down the line.

“It’s highly mutated, it looks very different and therefore is evading some of the protections we’ve put in place, both with vaccines and natural immunity,” she said. As if that weren’t enough, it also looks like it does “not respond to some of our currently available treatments.”

BA.2.75.2 has been spreading in Europe and Asia, but it’s not prominent enough here to rate a mention on the COVID-19 Data Tracker maintained by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. For now, it presents more of a “theoretical worry” and might never cause actual problems, Ferrer said.

Higher on her list of immediate concerns is the risk that California might be in for a “twindemic” this winter.

Health officials first raised the possibility of a twindemic in the summer of 2020, as they geared up for a double whammy of COVID-19 and seasonal flu. Thankfully, COVID-19 precautions helped keep the flu at bay in the first two pandemic winters.

This may be the year our luck runs out. Mask mandates are no longer in place, social distancing has pretty much fallen by the wayside, and capacity limits for events and public spaces are long gone. If the influenza virus shows up, it will have an easier time finding people to infect.

That’s been the case in Australia, where winter turned to spring last month. The peak number of laboratory-confirmed flu cases there reached levels not seen since at least 2017.

“They experienced a relatively severe flu season dominated by H3N2, which is what’s circulating here,” Ferrer said, referring to a strain of influenza. An updated version of H3N2 is included in the flu shots now available here.

Another ominous fact about Australia’s flu season: It started earlier than usual — in the middle of fall — and took off fast, Ferrer said. Normally, our flu season begins at the end of fall, in late November or December.

(As a reminder, it’s 100% OK to get a COVID-19 booster and a flu shot at the same time.)

California is getting a new law designed to fight back against doctors who give patients bad information about COVID-19. Starting Jan. 1, physicians will be subject to disciplinary action if they say things they know to be false or misleading.

The law was endorsed by the California Medical Assn., which represents nearly 50,000 doctors throughout the state. But critics — including many mainstream doctors who are strong proponents of vaccines and masks — are concerned the law could have unintended consequences.

As a new disease, our understanding of COVID-19 is still evolving. As a result, what was considered the standard of care last year or the year before is now out of date.

That leads to this corollary, as expressed by Dr. Eric Widera of UC San Francisco: “What was misinformation one day is the current scientific thinking another day.”

The law does not apply to doctors who say questionable things in a public forum like a political rally or on social media. A legislative analysis determined that a restriction like that probably would be overturned in court on 1st Amendment grounds.

Looking beyond California, housing advocates are expecting to see a big increase in the number of homeless people across the country when the federal government releases a report in the coming months. About 580,000 Americans were unhoused before the pandemic, and though it’s too soon to say how much that number will rise, early reports suggest cities of all sizes will help run up the tally.

Anti-eviction protections, emergency rental assistance programs and a child tax credit are all ending, shrinking the safety net that has kept many people off the street over the last 2½ years. On top of that, rising rents, a nationwide housing shortage and an unsteady economy are driving people out of their homes.

Sacramento, Portland, Ore., and Asheville, N.C., have experienced significant increases in homelessness. So have Prince George’s County in Maryland and the state of South Dakota. But numbers are falling in Houston, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. And in Boston, a concerted effort to move people from the streets and temporary shelters into permanent housing has resulted in a 25% decline in homelessness.

Speaking of Boston, health officials there said the concentration of coronavirus in the city’s wastewater had nearly doubled in the last two weeks. That could be an early sign that the uptick in COVID-19 cases seen in Europe is spreading to the East Coast.

Dr. Bisola Ojikutu, the public health commissioner there, called the trend “very concerning” because it could portend a season of “major strain” on Boston’s healthcare system. The city’s official coronavirus case count is actually down week-to-week, but that statistic is unreliable since it doesn’t include the results of home tests.

On to China, where the Communist Party is preparing for a major meeting in Beijing next week by locking down cities in the northern Shanxi province and in Inner Mongolia. Officials discouraged people from traveling during the “Golden Week” National Day holiday that began Oct. 1, but cases tripled anyway, from 600 to about 1,800. (For the sake of comparison, the U.S. is averaging more than twice as many new cases per day, even though China has more than four times as many people.) Many frustrated residents are hoping the country’s strict “zero-COVID” policy will be relaxed after the party meeting ends.

And finally, Japan welcomed droves of international tourists Tuesday after finally ending its pandemic border restrictions. People from 60 countries can once again make short-term visits, with no cap on the number of people who can arrive each day.

Tourists must be vaccinated and boosted, and they must present a negative PCR test within 72 hours of boarding a flight to the land of the rising sun. Once on Japanese soil, they’ll have to wear masks and sanitize their hands in many stores and restaurants.

Those rules aren’t deterring the Japanophiles who’ve been waiting nearly three years to eat sushi, ride bullet trains and visit the hot springs known as onsen. All Nippon Airways, or ANA, said the number of people booking flights to Japan jumped by a factor of five in the last week. The influx of visitors is expected to inject $35 billion into the Japanese economy.

David Beall of Los Angeles bought a ticket for his 13th trip to Japan, which will include stops in Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka. “Just being back in Japan after all this time is what I am most looking forward to,” he said.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: How long should I wait to get the new booster if I’ve recently had COVID-19?

Technically, you only have to wait long enough to stop isolating and be able to leave the house.

The current guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention say to isolate for at least five full days. At that point, if you’ve been fever-free for at least 24 hours without the help of medication and your symptoms have improved or resolved, you can rejoin the world as long as you wear a mask around other people for another five days. If you’re still sick on the sixth day, continue to stay home until your fever goes away for 24 hours, then wear a mask around others until the 10th day comes to an end. (You can keep wearing a mask beyond Day 10 if you like.)

Although you can get the bivalent booster right after you recover from COVID-19, that doesn’t mean you should.

If you’ve just fought off a coronavirus infection, your antibody levels are already high. The goal of the booster has already been accomplished, so a shot would be superfluous.

That’s why the CDC suggests you wait until three months have passed since your first COVID-19 symptoms appeared or you first tested positive for a coronavirus infection (whichever came first). A delay results in a stronger immune system response to the booster, according to studies cited by the agency.

But there’s a little wiggle room. For instance, if you’re in a place with a high COVID-19 community level, you might not want to wait as long as someone in a place with a low community level. Or, if you know your infection was not caused by BA.4 or BA.5 — the two Omicron subvariants targeted by the new booster — you might get the shot sooner rather than later.

Talk to your doctor if you’re not sure about the best booster timing for you.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

The concrete and glass structure in the photo above is the Robert B. Docking State Office Building, which sits across the street from the Kansas State Capitol in Topeka. Most of its 14 stories are empty, which is why state officials plan to raze it and put a three-story building there instead.

The project won’t be cheap, but $60 million of the cost will be paid for with federal funds intended to be used for pandemic relief as part of the American Rescue Plan.

Kansas says the construction counts as a “public health service,” and Troy Waymaster, who chairs the Kansas House Appropriations Committee, said it would be easier to practice social distancing in the new building than in one built in the 1950s. But the main reason to use pandemic relief funds for the project is that the state’s $1.6-billion allotment is burning a hole in its figurative pocket.

“We didn’t need it, to be quite honest,” Waymaster said.

The American Rescue Plan takes an expansive view of how the money can be spent. About $36 billion has been earmarked for infrastructure projects, according to an analysis by the Associated Press. That includes work on water and sewer systems, spending for roads and bridges, and projects to expand broadband access.

By contrast, less than $12 billion is going toward things that fit under the broad umbrella of public health.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in various ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, as well as resources for people experiencing domestic abuse.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.