Coronavirus Today: How COVID lies spread on Facebook

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, Oct. 4. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

They say a lie gets halfway around the world before the truth has a chance to get its pants on. That’s especially true if the lies are about COVID-19 and they’re being spread via Facebook.

This feels like the kind of platitude that’s easy to believe yet impossible to prove. But three researchers from the Dynamic Online Networks Lab at George Washington University have done so, and they explained how in a paper published last week in the journal Science Advances.

It turns out a multitude of factors contributed to the triumph of bad COVID information over good. Key among them was the fact that anti-science forces didn’t hesitate to share their opinions online, while those guided by evidence sat on the sidelines. By the time the latter group joined the fray, it was too late to make much difference.

The trio figured this out by examining Facebook community pages. These are places where members seek advice about topics of common interest, such as health and parenting.

The researchers began with pages that hosted discussions about vaccine safety in November 2019, just before the coronavirus became news. From there, they traced the pages’ outward links, then the links of those pages and so on until they had mapped an entire network of 1,356 interlinked communities that collectively claimed 86.7 million members.

Once the network was defined, the content of each page was assessed for its scientific validity. Pages were classified as “pro” if they endorsed and actively promoted positions in line with public health guidance; “anti” if they did the opposite; or “neutral” if they were focused on issues not directly related to health, such as organic cooking or pets.

By the time the researchers were done, they had identified 211 pro communities and 501 that were anti. In terms of users, however, the pro communities had the clear advantage, collectively claiming 13 million members while the anti communities had 7.5 million. Both camps were outnumbered by the 644 neutral communities, which had 66.2 million members among them.

After the network was built, the team — physics graduate student Lucia Illari, senior research assistant Nicholas J. Restrepo and physics professor Neil Johnson — could see how information flowed through it. Perhaps the most striking feature was that the anti communities were the first to broach the topic of COVID-19, and they did so in January, well before the World Health Organization declared a pandemic on March 11, 2020.

The antis were quick to influence the larger network by spreading their messages to neutral communities. After absorbing the information for several weeks, the neutrals felt comfortable sharing their own opinions about COVID-19. They were likely unaware that very little of the information they’d seen on Facebook was backed by the science available at the time.

The pro communities began discussing COVID-19 in earnest in February, and they mostly wound up talking among themselves — that is, not influencing anyone who actually needed to hear what they had to say.

Throughout 2020 — a “period of maximal societal uncertainty,” as the researchers put it — the neutral communities continued to move closer to the anti communities.

That mattered, because by the time the first COVID-19 vaccines came along, fewer people were willing to trust the public health officials who were asking them to roll up their sleeves. Among these formerly neutral vaccine skeptics were parents who made decisions not only for themselves but for their children, and often for their elderly relatives as well.

Facebook itself attempted to encourage the spread of science-based information about COVID-19 by including links to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention at the top of some community pages. But most of those links appeared on pages for anti communities (where they did little good), and few were seen by members of neutral communities (who might have benefited).

The team also determined that 1.3 million people had been exposed only to pro information about COVID-19, while 7.2 million had seen only anti information and 5.4 million had seen some of both. Among members of parenting communities, the imbalance was even more stark, with 503 people influenced solely by the pros and 1.1 million influenced solely by the antis.

“Unfortunately, many people were exposed to guidance that was not best science from their online communities of likely well-meaning but non-expert friends,” the study authors wrote. In some cases, those who followed that bad advice opted not to wear protective masks or decided to skip the COVID-19 vaccine. Those decisions could well have had deadly consequences, the researchers noted.

The map they created of the Facebook network showed that simply cutting off access to communities with extreme anti-science views wouldn’t increase users’ exposure to credible information about COVID-19. In fact, if anti pages were shut down, some neutral communities might leave Facebook too, putting them beyond the influence of pro communities.

A better solution would be for pro communities to create more ties to neutral ones, the researchers concluded. It would also be helpful to prevent anti communities from networking with neutral ones, they added.

It may be too late to change many minds about COVID-19, but the insights the researchers gained “can be used to tackle the question of online misinformation more generally,” they noted.

Let’s hope so.

By the numbers

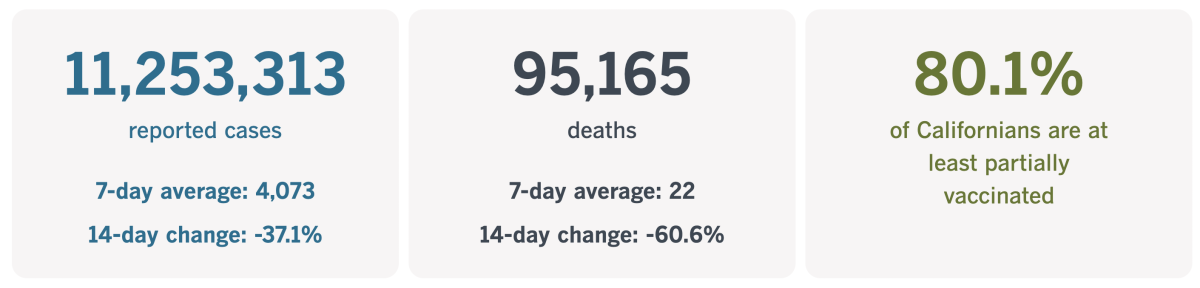

California cases and deaths as of 3:50 p.m. on Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

An unsung hero of the pandemic

In January 2020, when few Americans were aware of the mysterious cases of pneumonia spreading in China, Johns Hopkins University graduate student Ensheng Dong was paying close attention. His family lived about 600 miles from Wuhan, a distance that could easily become trivial in a fast-spreading outbreak.

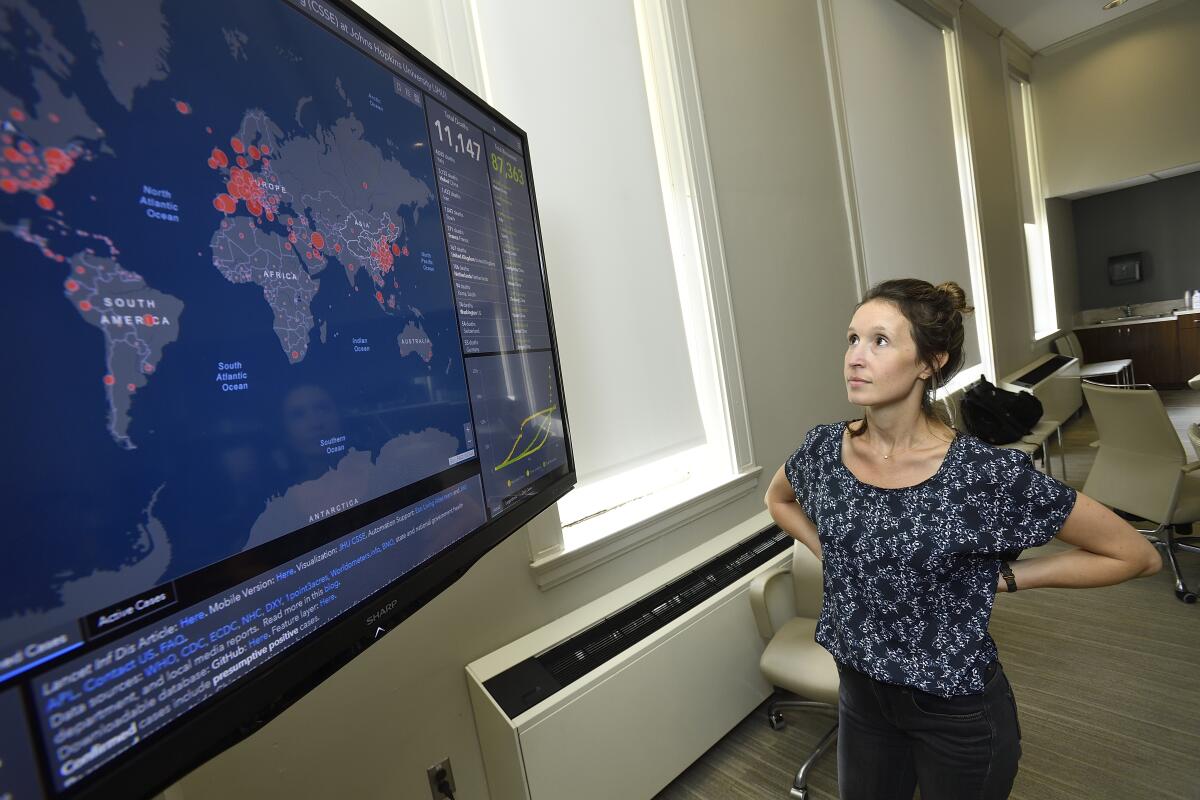

Dong shared his concerns with his PhD advisor, Lauren Gardner, an infectious disease modeler in the university’s engineering school. She suggested a productive way for Dong to channel some of his anxiety: Why not create a digital map to track the movement of the novel coronavirus?

He did it in a day. A few days later, the COVID-19 Dashboard made its public debut.

Gardner and Dong figured the map would be useful to a relatively small number of scientists and public health officials who were keeping tabs on the outbreak. They never imagined that by the end of March, it would attract close to 1 billion visitors.

Nor did Gardner anticipate that their dashboard would be the primary source of reliable information on infections and deaths when stay-at-home orders brought the U.S. economy to a sudden standstill.

“We knew it was important. I knew that the data had a lot of value, because I always did work where we needed that kind of data and didn’t have it,” Gardner told my colleague Corinne Purtill. “But I guess I didn’t expect to be the sole source of it.”

At the time, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was overwhelmed by rapidly spreading cases on U.S. soil. Officials were struggling to identify new infections and trace their contacts in hopes of containing the outbreak. The World Health Organization seemed to be in over its head as well, waiting more than a month to upgrade the situation from an international public health emergency to a full-blown pandemic. Launching a tracker wasn’t a priority for either the CDC or the WHO.

So when healthcare providers, government officials, journalists and anxious citizens wanted to know what was going on, the Hopkins COVID-19 Dashboard became the go-to place for dependable information.

Initially, Gardner and members of the growing tracker team were able to import data by hand. But the more the virus spread, the more unworkable that became.

As the number of countries reporting cases grew, the engineers worked to verify and standardize the data that populated the dashboard. Before long, they deployed web-scraping tools to gather the numbers they needed from official health databases. (Those numbers later included data on coronavirus testing and COVID-19 vaccinations.)

“It was really just a continually adaptable system that we were having to develop,” Gardner said. “We were just working around the clock for that year.”

Gardner decided early on that the tracker would only include information that was available to the public. That way, anyone who doubted the numbers they reported would have a clear way to verify them. At times, that meant rejecting offers from state and regional agencies to share case counts that they weren’t ready to make official.

“Make it public, and then we’ll put it on our data file,” Gardner said she told them.

That embrace of open data has been key to the tracker’s success, said Dr. Leana Wen, a professor of health policy and management at George Washington University and longtime Gardner fangirl. The transparency baked into the dashboard made it a reliable resource for decision-makers at all levels, she said.

As the dashboard’s dominance grew, so did its negotiating clout. That helped the engineers get some of the sensitive demographic data they sought, allowing them to see the degree to which the pandemic wasn’t affecting people of all races and ethnicities equally.

“That power, just because we had so many eyeballs, was something that was really helpful,” Gardner said. “But it didn’t last.”

It wasn’t the fault of her team. The problem was that quality data was getting harder to come by as people embraced rapid home tests. Even if the results were reported to authorities, they weren’t as reliable as tests processed in certified labs. Plus, as the pandemic dragged on, budgets for public health agencies were reduced and information was shared less frequently. Those trends prompted Johns Hopkins to announce last month that the dashboard would be scaled back.

Gardner told Purtill she’s frustrated that even a crisis like COVID-19 wasn’t enough to get government officials on board with standardizing the exchange of information that could help squelch a future outbreak. She called the situation “disheartening.”

Still, the tracker will go down in history for setting “a new standard for disseminating authoritative public health data in real time,” according to the Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation. The folks there should know: They bestow the prestigious Lasker Awards for achievements in medical science, which are sometimes referred to as “America’s Nobels.”

The foundation awarded Gardner the 2022 Lasker-Bloomberg Public Service Award last week.

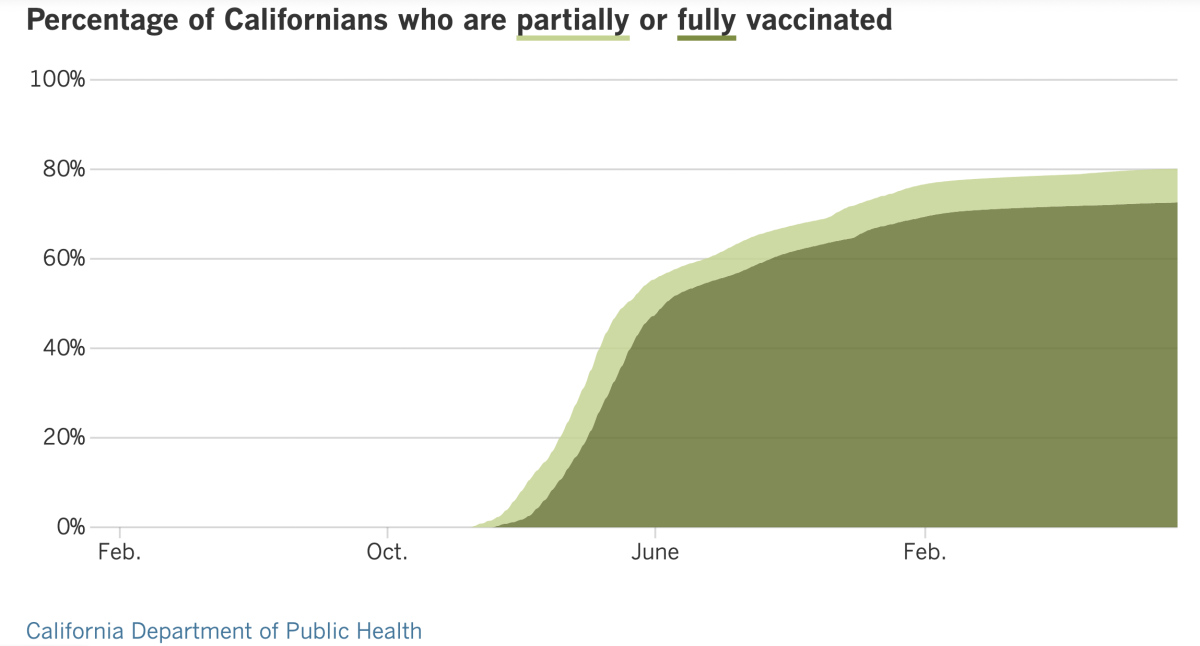

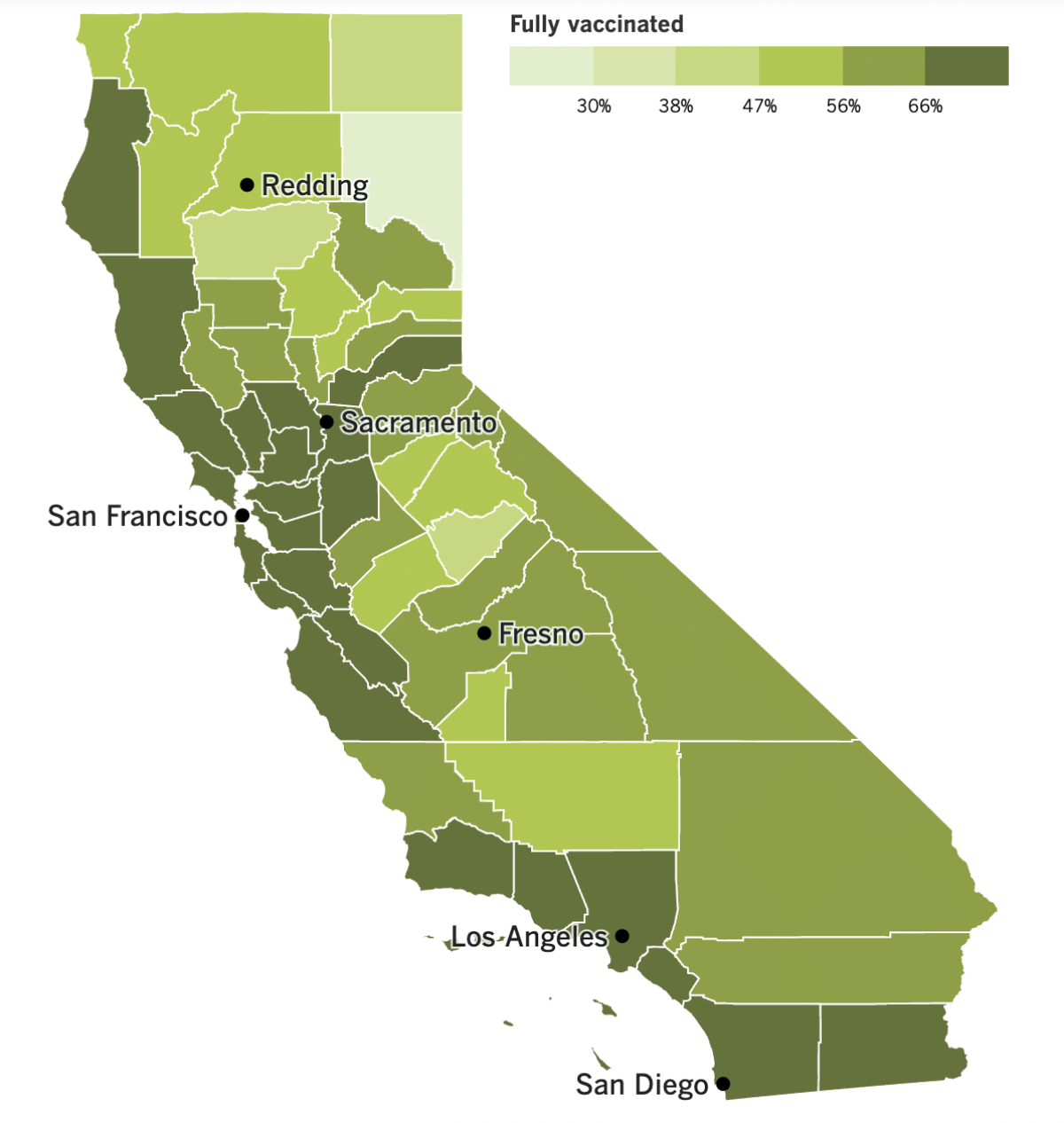

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

Coronavirus cases and deaths are continuing to fall, but the pandemic still isn’t over.

You might hear otherwise from politicians or TV pundits. But take their pronouncements with a huge grain of salt, because the official call will come from the World Health Organization — and it will be based on actual data, not public opinion.

“The definition of a pandemic is an outbreak of disease that has then spread beyond any one or two countries to a global spread,” said UCLA epidemiologist Dr. Robert Kim-Farley.

That certainly applies to the current situation.

At some point, experts will have to determine a level of cases and deaths that can serve as a baseline going forward. The U.S. averaged 322 COVID-19 deaths per day over the week ending Tuesday. That’s the lowest number since before the surge of the Omicron subvariant BA.5. But if you multiply it by 365 you get 117,530 COVID-19 deaths per year — more than triple the typical number of flu deaths.

Whatever the acceptable number of COVID-19 deaths turns out to be, we’ll need to maintain it for several months before scientists will say we’re out of the pandemic woods. My colleagues Luke Money and Rong-Gong Lin II put it in terms Californians can understand: “Declaring the end too soon could be like sounding an all-clear announcement after a major earthquake when there’s still the potential for significant aftershocks.”

Some of those aftershocks could come from new coronavirus variants or subvariants. We don’t know which one may become the new BA.5 (which accounts for an estimated 81.3% of coronavirus specimens now circulating in the U.S.), but Dr. Anthony Fauci said it’s a good bet that some new strain will make a run in the late fall or winter.

Fauci has his eye on a subvariant called BA.2.75.2, which he called “suspicious.” Dr. Benjamin Pinsky, director of Stanford’s Clinical Virology Laboratory, also flagged BA.2.75.2 as “the one that we’ve been most concerned about recently.”

It’s not big enough for the CDC to track it separately from BA.2.75, which was responsible for nearly a quarter of U.S. cases in early July and is still causing an estimated 1.4% of the nation’s infections. Only one case involving BA.2.75.2 has been identified at the Stanford lab.

But a preliminary study published last month found that the subvariant was particularly good at evading the the antibodies produced by vaccines and past infections. It was also less susceptible to Evusheld, a monoclonal antibody offered to people with compromised immune systems.

BA.2.75.2 isn’t the only potential troublemaker on the horizon. Other experts nominated Omicron subvariants called BQ.1.1, BA.2.3.20 and BF.7 (also known as BA.5.2.1.7). BF.7 is currently the most prevalent of these subvariants, accounting for an estimated 3.4% of coronavirus specimens active last week in the U.S., according to the CDC.

Here’s one sign that the pandemic is winding down: The Los Angeles City Council voted Tuesday to end eviction protections for tenants who fall behind on their rent due to COVID-19. Evictions will be allowed to resume on Feb. 1.

The city implemented the protections in March 2020 out of fear that the economic disruption caused by stay-at-home orders would deprive people of the income they needed to pay rent. Allowing people stay in their apartments helped prevent a surge in homelessness and averted some coronavirus spread.

In addition to permitting evictions, the council’s vote will allow owners of rent-controlled apartments to increase the rent they charge for the first time in nearly three years. However, some other renter protections may be made permanent.

The L.A. County Board of Supervisors voted 3 to 2 last month to allow the county eviction moratorium to sunset at the end of the year. Supervisor Sheila Kuehl, who wanted to keep the protections in place, noted that the county’s homeless population rose just 4.1% between 2020 and 2022 after increasing by 25% between 2018 and 2020.

“I think the headline will be: ‘This board must love homeless people.’ They are going to make so many more of them,” Kuehl said.

Meanwhile, the CDC has relaxed its mask recommendations for hospitals and other healthcare facilities. In counties with high community COVID-19 levels, universal masking is still recommended in settings where patients are present. But in places like employee break rooms or staff meeting rooms, healthy workers can remove their face coverings, the agency said.

When COVID-19 community levels are medium or low, healthcare facilities have the CDC’s blessing to drop their universal mask rules. Face coverings are still recommended for people with a suspected or confirmed coronavirus infection, or any other kind of respiratory infection. They’re also advised for people who were in close contact with an infected person in the previous 10 days, and for those who live or work in a place that’s experiencing an active coronavirus outbreak.

The CDC’s new stance doesn’t affect California, since the state Department of Public Health requires universal masking in all healthcare settings and long-term care facilities.

President Biden’s controversial COVID-19 vaccine mandate for federal contractors was back in court this week. A lawyer for the administration sought to persuade appellate judges in New Orleans to vacate a ruling that prevented the vaccine mandate from being enforced in Indiana, Louisiana and Mississippi.

A federal judge in western Louisiana had blocked the mandate on the grounds that Biden didn’t have the authority to order it in the first place. That position was reiterated Monday by a lawyer from the Louisiana attorney general’s office. The Biden administration lawyer countered that federal law gives the president authority to implement rules to streamline the way its contracts are managed.

And finally, the State Appeals Board in Iowa has rejected claims from 52 prison inmates who asked for $1 million apiece as compensation for being given super-doses of COVID-19 vaccine last year.

Each of the inmates received six times the proper amount of vaccine after the prison switched from Moderna to Pfizer-BioNTech shots and the nurses administering them didn’t realize the Pfizer product needed to be diluted with saline. Two nurses were fired after the mistake came to light, but the appeals board turned down the request for payouts on the grounds that the federal Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act gives states immunity from claims related to vaccine administration.

A spokesman for the prison said the over-vaccinated inmates experienced normal side effects, including body aches, fatigue and sore arms.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Can I get a COVID-19 booster and flu shot at the same time?

Absolutely. Not only is it perfectly safe, it’s recommended.

In fact, the CDC encourages healthcare providers to offer patients all of the vaccines and boosters for which they are eligible. Each vaccine will work equally well whether it’s given alone or in tandem with others. Side effects will be the same as well.

It’s OK to combine your COVID-19 booster with any version of the flu vaccine, including a standard quadrivalent shot, an adjuvanted shot or a high-dose shot. If you decide to double up, avoid getting both shots in the same limb, if possible.

“I really believe this is why God gave us two arms — one for the flu shot and the other one for the COVID shot,” Dr. Ashish Jha, the White House COVID-19 response coordinator, said in a recent briefing.

Los Angeles County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said that with fewer people wearing masks, the upcoming flu season is likely to be more active than the last two. That makes it all the more imperative to get both shots.

“We do encourage everyone to take advantage of the many vaccination sites where you’re going to be able to get your flu vaccine and your COVID fall booster at the same time,” she said.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

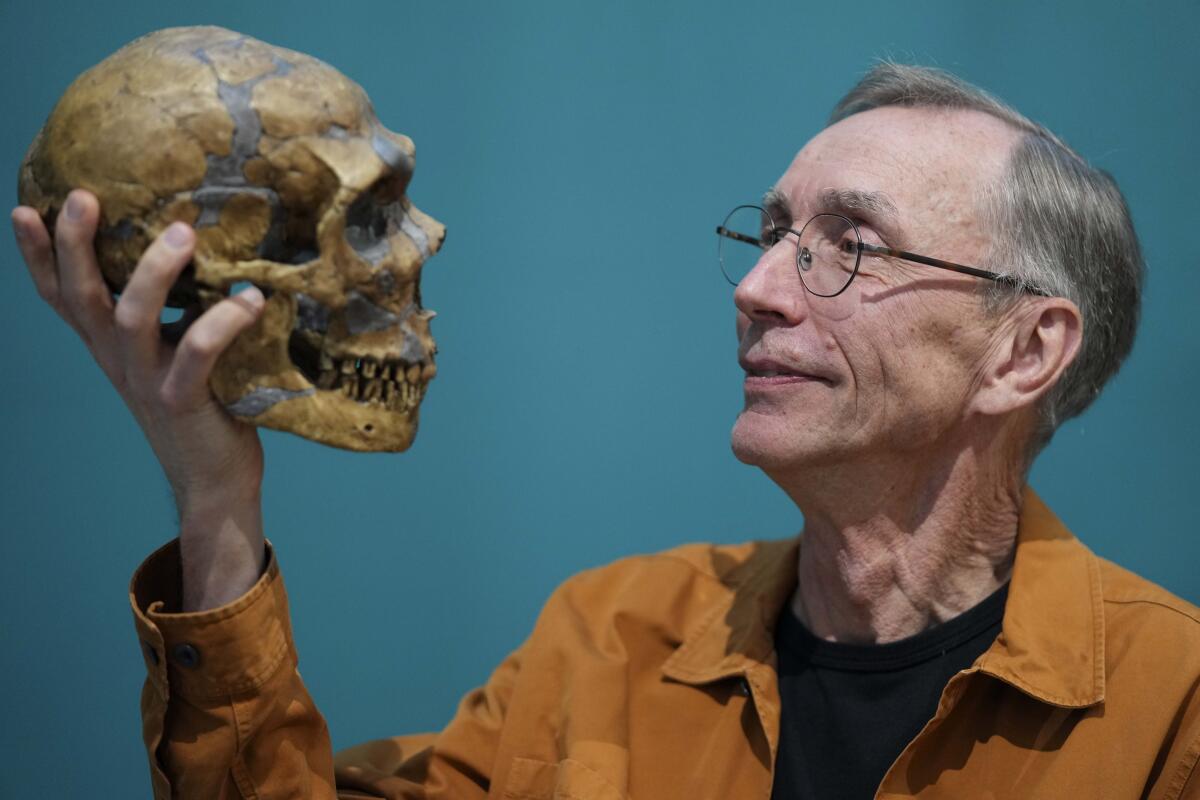

The man in the photo above is Svante Paabo, recipient of this year’s Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. He’s holding a replica of a Neanderthal skull because his work made it possible to decode the genome of our now-extinct cousins (along with that of another related species, the Denisovans).

What does that have to do with the coronavirus? Paabo and his colleagues figured out that as a result of interbreeding, most modern humans got between 1.8% and 2.6% of their DNA from Neanderthals. Some of those genes affect the workings of our immune systems — including our risk of becoming severely ill with COVID-19.

In 2020, Paabo co-wrote a study published in the journal Nature that identified a cluster of genes inherited from Neanderthals that were linked to an increased risk of hospitalization and respiratory failure when battling a coronavirus infection. That particular group of genes (known as a haplotype) is shared by about half of the people in South Asia, 16% of people in Europe and 9% of Americans. It is not seen in people in East Asia and Africa.

When the study was published, Paabo called it “striking that the genetic heritage from the Neanderthals has such tragic consequences during the current pandemic.”

But other scientists said those Neanderthal genes must be doing something useful if they’ve managed to hang onto their place in the human genome for so many years.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in various ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, as well as resources for people experiencing domestic abuse.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.