Coronavirus Today: What’s wrong with the CDC?

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, Aug. 23. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

Perhaps there have been points during the pandemic when you’ve felt let down by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Maybe it was back in the early days of the outbreak when the CDC used a faulty reagent in its initial batch of coronavirus test kits, leaving the country in the dark about how widely the virus had spread.

Maybe it was when the agency did a 180 on face masks, suddenly recommending them after insisting for weeks they were only necessary in healthcare settings.

Maybe it was when the CDC finally acknowledged that the coronavirus spreads mainly through the air but declined to pair that update with any new guidance on how to stay safe.

Or maybe it was when you learned that being “fully vaccinated” against COVID-19 didn’t necessarily mean you were “up to date” with your shots.

Sadly, there are many options to choose from. And they’re not limited to COVID-19 — the early response to the monkeypox outbreak hasn’t exactly vindicated the agency.

You might have some harsh words for the CDC. So does its director, Dr. Rochelle Walensky.

“To be frank, we are responsible for some pretty dramatic, pretty public mistakes,” Walensky said in a video circulated last week to the CDC’s 11,000 employees.

Those mistakes can’t be written off as reasonable reactions to a never-before-seen threat, she added. Nor can they be blamed on political interference from either the Trump or Biden White House.

Walensky’s sobering assessment followed a fact-finding mission that included interviews with more than 100 public health experts from both inside and outside the CDC, my colleague Melissa Healy reports.

“An honest and unbiased read of our recent history will yield the same conclusion,” Walensky said. “It is time for CDC to change.”

At the top of her list is improving its ability to explain a health threat to the public — and doing so early, often and authoritatively.

To succeed, CDC researchers will need to streamline the way they gather data from state and county public health agencies and large healthcare organizations. Then they’ll need to digest that data in short order so they can explain it to the public and use it to justify any guidance they have to offer.

The faster the CDC’s public health pronouncements are issued and the easier they are to understand, the more compliance it can expect, Walensky said. The agency will also do a better job of communicating with other government agencies so they don’t contradict one another and call everyone’s credibility into question.

All this hinges on better cooperation with local health agencies, which aren’t required to share data with the CDC if they don’t want to. At times during the pandemic, Florida, Texas and a variety of other states have declined to let the CDC know how many of their residents were getting vaccinated, how many were infected, and how many had died of COVID-19. Their omissions forced the agency to make assumptions about the missing data and proceed with potentially significant blind spots.

A bill introduced in Congress last month — the Improving DATA in Public Health Act — could help the CDC overcome those obstacles. Congress could also help by giving the CDC more authority to shift its budgets around during a health emergency, and by making up for years of reduced funding that left public health agencies ill-equipped to respond to COVID-19.

Health departments could have gotten an earlier jump on monitoring the coronavirus’ shenanigans if they had already established strong wastewater surveillance systems and set up labs to conduct routine genetic sequencing of viral specimens. Now they’re in place, but the CDC needs extra money to maintain and improve them.

An agency-wide reboot of its capabilities and culture sure sounds like a tall order. But the CDC has done difficult things in the past. In its first decade alone it eliminated three major threats to Americans’ health: smallpox, malaria and polio.

“Sure they can reform themselves,” said Lorien Abroms, who teaches public health communications strategy at George Washington University. “They came from a place of greatness. We used to lead the world on epidemiological intelligence. I definitely think we can go back to that.”

By the numbers

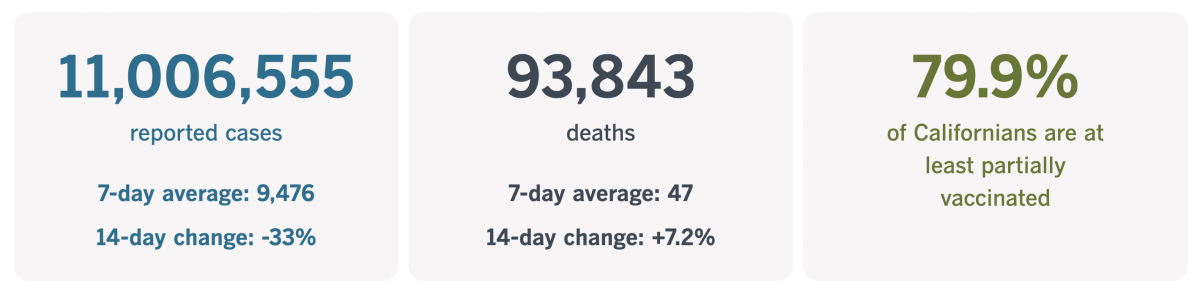

California cases and deaths as of 3:28 p.m. on Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Is there still a need for contact tracing?

After the initial Omicron surge this winter pushed the number of coronavirus infections to record heights, the CDC made a practical decision about contact tracing: It was no longer a feasible way to keep case numbers in check.

“Universal case investigation and contact tracing are not recommended for COVID-19,” the agency said on its website. Instead, it advised local health departments to prioritize high-risk settings, such as nursing homes and prisons.

The track record of contact tracers in Los Angeles County shows why this advice came about. In January, there were weeks when fewer than 10% of the people who were supposed to be interviewed actually were.

They’ve done a little better during the second Omicron wave this spring and summer, reaching close to 30% of the people assigned to them. But even when they got through, their interviews rarely led to follow-up calls to notify others that they might have been exposed, my colleague Emily Alpert Reyes reports.

The contact tracers’ low success rate wasn’t necessarily their fault. In July, there were only about 100 staffers available to reach the thousands of residents who became newly infected each day. Earlier in the pandemic, that work was spread among roughly 2,800 people.

Low staffing wasn’t the only hindrance. Omicron and its subvariants have shorter incubation times than their predecessors, so the window for reaching exposed people before they become spreaders is smaller.

Thanks to general pandemic burnout, many residents aren’t inclined to respond to the calls, emails and text messages they get from contact tracers. (The L.A. County Department of Public Health is trying to overcome this apathy by offering gift cards to those who get in touch.)

And let’s not forget that a large proportion of infections are never reported to the county in the first place.

When you put it all together, it becomes clear that the odds of making a significant dent in the spread of COVID-19 are stacked against contact tracers.

That’s certainly the view of Adriane Casalotti, chief of government and public affairs with the National Assn. of County and City Health Officials.

Contact tracing “is not really making the impact that it did at one point,” Casalotti told Alpert Reyes. “With communities broadly reopened, it’s very difficult to say how many contacts you had, and even if you can say that, you may have 20 or 30 or 40 contacts. ... The logistics of actually contacting those people is very difficult. There’s not enough time in the day.”

Things were different in March 2020, when the number of infections due to the “novel coronavirus” was still small enough for epidemiologists to aim for containment. After the outbreak became too big to control, contact tracers were still able to slow things down and “buy people time” until COVID-19 vaccines became available, said Andrew Noymer, an epidemiologist and demographer at UC Irvine who studies infectious diseases.

But at this stage of the pandemic, when so many people are taking so few precautions to avoid the coronavirus, “I just don’t see that we’re going to contact trace our way out of this,” he said.

Other localities — including New York City and Washington, D.C. — have recognized this and wound down their contact-tracing efforts. The CDC reiterated its stance that contact tracing is only worthwhile in high-risk settings when it streamlined its COVID-19 guidance this month.

The L.A. County Department of Public Health has a team dedicated to contact tracing in nursing homes and correctional facilities. But it’s not ready to end contact tracing for the general public, especially when it comes to cases involving elderly residents and people in neighborhoods where transmission levels are particularly high.

That decision makes sense to some experts.

“Dismantling the infrastructure for being able to effectively do contact tracing does not serve public health at all,” said Dr. George Rutherford, an epidemiologist at UC San Francisco.

Preventing infections is only one benefit of contact tracing, he noted. Learning that you’ve been exposed could result in earlier testing and — if warranted — quicker treatment with Paxlovid, a drug that works best when started early.

Dr. John Swartzberg, a clinical professor emeritus at UC Berkeley School of Public Health, is also a fan.

“Any contact tracing is good contact tracing — as long as the resources are not being taken from other things that are more effective,” he said.

Its value will rise when case numbers fall and contact tracers won’t be so overwhelmed, he added. The easiest way to make sure they’ll be in place at that point is to not get rid of them in the first place.

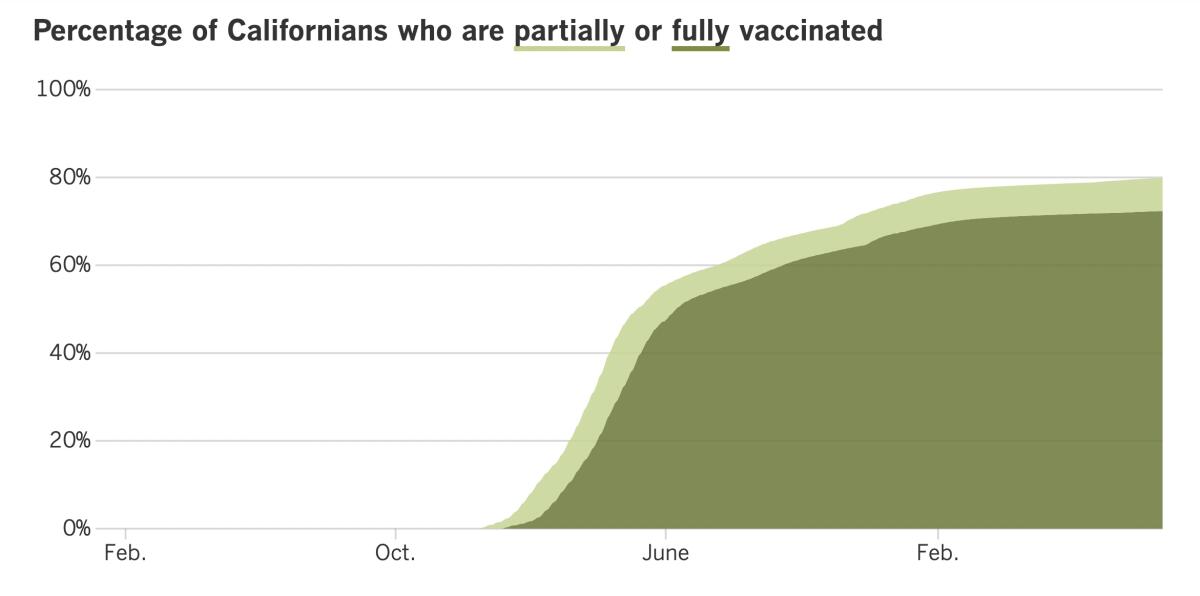

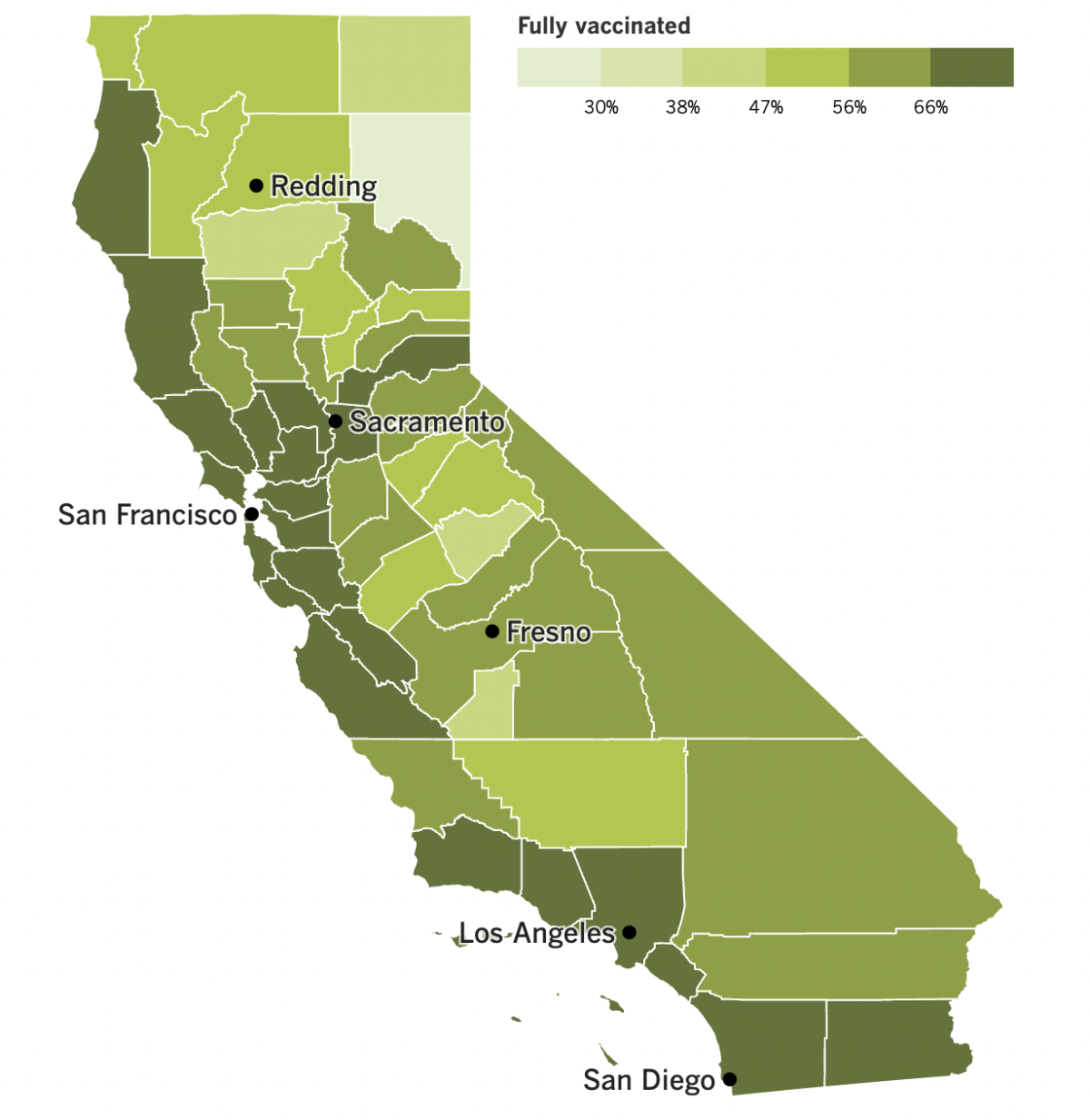

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

America, I’d like to introduce you to the Omicron subvariant called BA.4.6. It’s not causing much mischief in the U.S. — at least not yet — but scientists are watching it closely to see if it stays that way.

The CDC estimates that BA.4.6 accounts for 6.3% of the coronavirus specimens now in circulation in the U.S. That’s up slightly from 5.6% last week and 5% the week before. (BA.5 still dominates, with 89% of the coronavirus market share.)

BA.4.6 is less prevalent in California and other Western states, making up just 2.4% of samples sequenced in the two federal regions that encompass the Pacific coast. It’s even less common in Los Angeles County, accounting for about 1.5% of cases here.

But it has a much bigger footprint in the region that includes Iowa, Kansas, Missouri and Nebraska, making up nearly 16% of cases in those states last week. That suggests BA.4.6 may have the potential to overtake BA.5 and perhaps spark a new wave of infections, experts said.

Past outbreaks in California have hit public transit employees harder than other workers, a new study shows. From the start of the pandemic up through May of this year, there were 24.7 coronavirus outbreaks for every 1,000 workplaces throughout the state. But the odds of an outbreak were much higher for public transportation industries — 3.5 times higher for workers in air transportation and five times higher for workers in bus service and other forms of urban transit.

The study, which was conducted by researchers at the California Department of Public Health, identified 340 outbreaks in public transportation industries that resulted in 5,641 coronavirus infections and 537 COVID-19 deaths. The risk of death due to COVID-19 was twice as high for bus and rail service workers as it was for California workers as a whole.

The findings offer some justification for L.A. County’s mask mandate in public transportation settings. The study authors noted that essential workers in these industries should get priority access to COVID-19 vaccines and other prevention tools.

In other California news, a church in San Jose that faced a huge fine for disregarding state and county rules about indoor gatherings will not have to pay up, a state appeals court ruled.

Calvary Chapel San Jose, along with its pastors, were held in contempt of court for holding large religious services in defiance of health orders aimed at preventing coronavirus spread. The Supreme Court ruled in 2020 that those restrictions were justified. A year later, after the composition of the court changed, the high court said limits on indoor worship infringed on the constitutional right to exercise one’s religion freely.

That ruling prompted the California appellate court to toss the roughly $200,000 fine last week. But Santa Clara County officials said they would still go after the church for $2.3 million worth of penalties it racked up for violating other public health rules, including ones requiring face masks.

There’s been some action on the COVID-19 vaccine front. Pfizer said Tuesday that the vaccine it developed with BioNTech for children under 5 was 73% effective. The data behind that figure was gathered between March and June as part of a trial that tested three shots of the low-dose vaccine against three shots of a placebo.

The company said there were 13 cases of COVID-19 among the 794 children — all between the ages of 6 months and 4 years — who were randomly selected to get the vaccine. Another 351 children got the placebo, and 21 of them came down with COVID-19.

A similar vaccine from Moderna is also available for infants, toddlers and preschool-age kids. However, only about 6% of children between the ages of 6 months and 4 years have received a COVID-19 vaccine since they became available in June, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Teens now have a new option for their primary COVID-19 vaccination series. The Food and Drug Administration authorized Novavax’s COVID-19 vaccine for emergency use in adolescents ages 12 to 17 on Friday, and the CDC recommended it on Monday. The two-shot series uses harmless coronavirus proteins to prime a recipient’s immune system, an old-school technology meant to appeal to those who aren’t comfortable with the new-fangled mRNA vaccines.

Pfizer and BioNTech have asked the FDA to authorize their new COVID-19 shots that have been tweaked to target the BA.4 and BA.5 strains as well as the original version of the virus. If the FDA gives its blessing, and then the CDC follows suit, the new shots could be available for a fall booster campaign in a matter of weeks.

The federal government has already struck a deal to buy 105 million doses of the targeted booster shot. It also has a contract to buy 66 million doses of a targeted vaccine from Moderna, which is expected to go before the FDA soon.

Dr. Ashish Jha, the White House COVID-19 response coordinator, is eager to see the updated vaccines go into Americans’ arms.

“It’s going to be really important that people this fall and winter get the new shots,” he said. “It’s designed for the virus that’s out there.”

And finally, Dr. Anthony Fauci has set a date for his retirement — December 2022.

The nation’s top infectious diseases expert had already said he would leave the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases before the end of President Biden’s current term. Now, after 54 years at NIAID, there are only a few months left.

During his tenure, the country has weathered outbreaks of HIV/AIDS, SARS, H1N1 flu and Ebola. But it was the COVID-19 pandemic that made him a household name. His institute was instrumental in the speedy development of COVID-19 vaccines, and his straight-talking style endeared him to many Americans — though not all of them.

“If ever there was a situation where you wanted a unified approach and everybody pulling together for the common good, it would be when you’re in the middle of a public health crisis,” Fauci said.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Is there any reason to keep my cloth masks?

This question comes from a reader who came upon her little-used cloth masks while doing some back-to-school cleaning and wondered whether they served any purpose in a world where disposable surgical masks and higher-quality N95, KN94 and KN95s are readily available.

It’s true that some masks are better than others, but it’s also true that any mask is better than no mask at all, said Dr. Bruce Y. Lee, a professor at the City University of New York Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy who has studied the value of masks.

“Anything in front of your mouth will be able to block — at least to some degree — the respiratory droplets that come out of your mouth, and maybe it will block droplets in the air that come into your nose or mouth,” he said.

A cloth mask might not prevent all viral particles from entering your airways, but reducing the amount of virus that makes it through may mean the difference between a mild and a severe case of COVID-19, he added: “It’s not just about breathing in the virus, it’s how much virus you breathe in.”

Lee offered one more use for a cloth mask: It can extend the life of an N95 respirator. Although N95s were designed to be single-use face coverings, research during the pandemic has shown that they remain effective through several wearings, and a cloth mask can help protect it from being damaged.

“If you have a choice of wearing an N95, you should go for the N95,” Lee said.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

The photo above shows students in the Philippines as they lined up Monday for the first day of school.

It’s more than the first day of a new academic year — it’s their first time heading back into classrooms since pandemic lockdowns sent millions of pupils home back in 2020.

In the U.S., some schools shut down for just a few months. Even those that remained closed for most of the 2020-2021 school year welcomed students back to campus last fall, and they kept their doors open even as Delta and Omicron swept through their communities.

Not so in the Philippines. Former President Rodrigo Duterte was afraid that having millions of children gather in person would spark new outbreaks. He stuck with that stance until his term ended on June 30.

The extended school closures didn’t help the Asian nation improve its alarmingly low literacy rates. A study last year by the World Bank reported that about 90% of Filipino children under 10 couldn’t read and understand a simply story, a condition it called “learning poverty.”

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in various ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, as well as resources for people experiencing domestic abuse.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.