Column: Raking in profits, Moderna denies government scientists credit for the COVID vaccine

While much of the world was sent into a panic by the sudden emergence of the Omicron variant of the coronavirus, Moderna Inc. weathered the shock pretty well.

Indeed, its shares have gained more than 25% in value since the World Health Organization labeled the microbe a “variant of concern” and gave it a Greek-letter designation Friday.

That includes a 12% gain Monday, the first full trading day since Thanksgiving, and a retrenchment of about 7% during Tuesday’s trading.

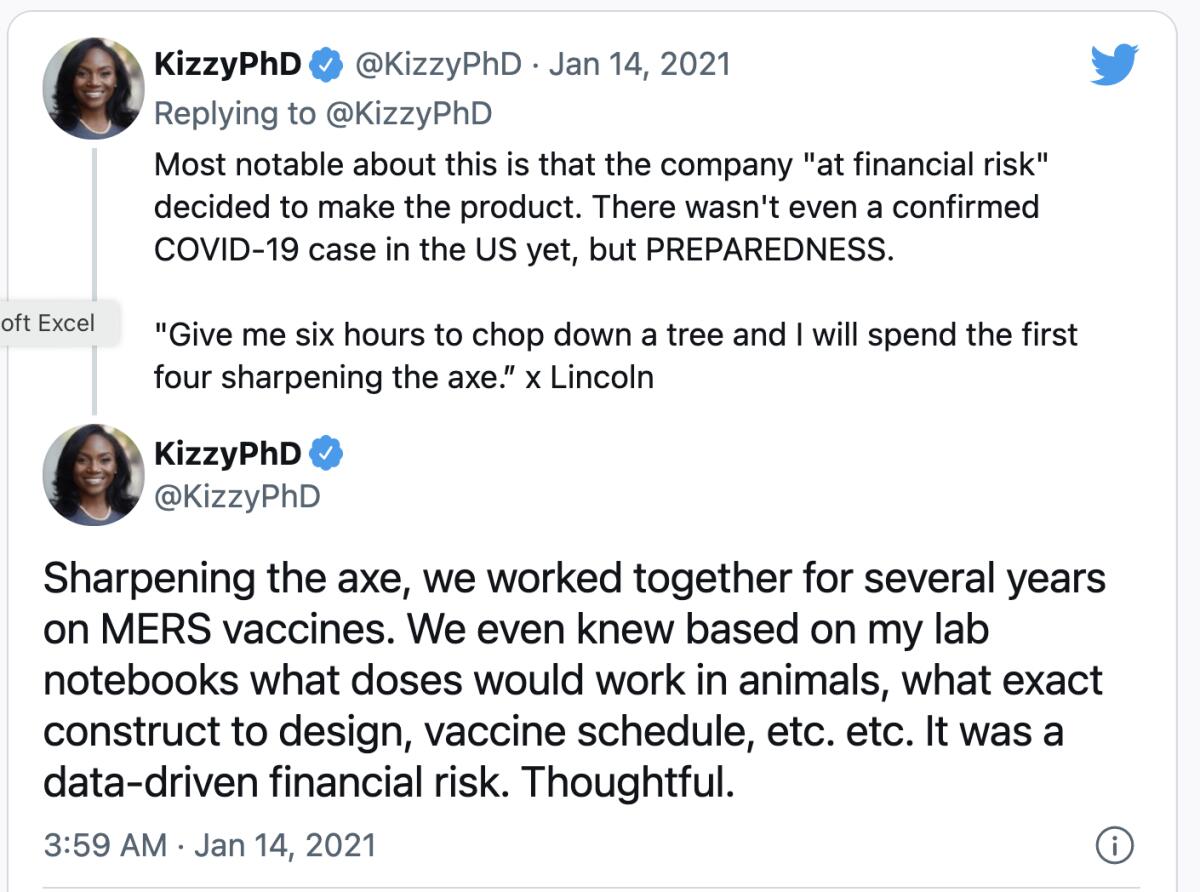

We even knew based on my lab notebooks what doses would work in animals, what exact construct to design, vaccine schedule, etc., etc.

— Former government scientist Kizzmekia Corbett

The obvious reason for the gain is that as a manufacturer of one of the two leading COVID-19 vaccines, Moderna stands to make a tidy profit from the resurgent crisis.

The company recorded about $10.7 billion in revenue and more than $7.3 billion in profit from its vaccine in the first nine months of this year, and expects $17 billion to $22 billion in sales from the product next year.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Moderna’s chief executive, Stéphane Bancel, said Monday that he expected that existing vaccines won’t work as well against the new variant as they have against the old ones but that Moderna is already preparing anti-Omicron booster formulas.

Moderna’s fortunes are closely tied to the COVID-19 vaccine, its only commercial product.

(Pfizer, the maker of a similar, competing vaccine, has a broad product line and is nearly six times as large as Moderna as measured by revenue and recorded more than twice Moderna’s profits, or $18.6 billion, in the nine months that ended Sept. 30; its shares have risen by only about 6% since the WHO announcement.)

But all is not bright for Moderna. Thanks in part to the astounding success of its vaccine, the company is also locked in a fierce battle with the U.S. government over credit for developing the vaccine.

That comes as the appearance of Omicron has intensified calls for an international waiver of intellectual property rights to the vaccines for the duration of the pandemic emergency.

The patent dispute centers on the work of three scientists associated with the National Institutes of Health — John Mascola, Barney Graham and Kizzmekia Corbett. (Corbett is now at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.)

They were collaborating at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, or NIAID, with Moderna scientists before COVID-19 appeared.

Moderna’s founders are making a mint from COVID vaccines. But the company is failing its commitment to provide shots to the less wealthy nations.

The NIH maintains that their contributions were significant enough to rank them as co-inventors of the Moderna vaccine. That would make the government a co-owner, with the right to license the vaccine to manufacturers around the world without Moderna’s permission.

Moderna does acknowledge in its patent filing that the government seeks to have Mascola, Graham and Corbett listed as co-inventors. But it says it has made a “good-faith determination” that they did not co-invent the vaccine.

“For those who would seek to twist Moderna’s good faith application of U.S. patent law into something else, nothing could be further from the truth,” the company said in a Nov. 11 statement.

Moderna also says that it offered to make the government co-owner of the vaccine, “including the right as co-owners to license the patents as they see fit.” But that plainly has not been enough to resolve the dispute, since NIH Director Francis Collins said at a Reuters healthcare industry conference in November that the dispute will probably land in court.

“The key question is why the government said no to this offer,” observes Zain Rizvi, a research director on vaccines at the advocacy group Public Citizen. “Did Moderna want something in exchange that the USG did not want to give up?”

NIH and Moderna haven’t responded to questions about why the Moderna offer may have been unsatisfactory.

Pfizer and Moderna will rake in the big bucks from their COVID vaccines. That’s a sign of a broken system.

It’s possible, however, that NIH believes that co-inventorship credit is more important than acquiring merely the right to license the vaccine.

“I think Moderna has made a serious mistake here in not providing the kind of co-inventorship credit to people who played a major role in the development of the vaccine that they’re now making a fair amount of money off of,” Collins said.

At stake in the dispute are not only profits measured in the billions of dollars but also the rollout of the vaccine to other countries, especially less-developed countries where the shots’ availability has lagged well behind. Critics of the pharmaceutical industry contend that the slow rollout in the less-developed countries stems from drugmakers’ profit-seeking.

The anti-poverty organization Oxfam has calculated that the three leading makers of the mRNA vaccines — Moderna, Pfizer and Pfizer’s partner BioNTech — will collect pretax profits of about $34 billion this year, or “over a thousand dollars a second.... The monopolies these companies hold have produced five new billionaires during the pandemic, with a combined net wealth of $35.1 billion.”

Meanwhile, the vaccination rate in poorer countries is mired in single digits.

There’s even more to the story. It concerns the government’s role in funding corporate research, which is massive, and its reluctance to demand the rights to successful research and development that taxpayers are entitled to by law.

The federal government has poured billions into COVID-19 vaccine research, but will Americans reap the profits?

The federal government provided Moderna with about $1.4 billion in direct funding to develop the vaccine, and as much as $8 billion to $9 billion more in support for basic research and clinical testing, by the estimate of David Kessler, chief science officer of the Biden administration’s COVID-19 response team.

The National Institutes of Health maintains that its scientists co-invented the vaccine in collaboration with Moderna scientists. Moderna’s patent application for the vaccine doesn’t name the NIH collaborators as co-inventors — an indication that the company is intent on “airbrushing” the government scientists out of the picture, as Sam Pizzigati of the Institute for Policy Studies put it.

Placing the government scientists’ names on the key patents as co-inventors would give the federal government a powerful right to license the vaccine to manufacturers without Moderna’s permission, posing a significant threat to Moderna’s current stranglehold on manufacturing. That would be a boon not only to Americans but also to residents of countries around the world who are exposed to COVID-19 because of a scarcity of vaccines.

Federal law already gives the government “march-in rights” over the vaccine, allowing it to require that Moderna license the manufacturing rights to others, for a price, if it determines that the company isn’t doing enough to make the vaccine available.

The march-in rights stem from the government’s financial contribution to the vaccine’s development. Yet the government has never accessed those rights, even though they were granted for products based partially on government funding by the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980.

Moderna’s decision not to credit the government team is something of a gamble for the company itself, however. That’s because failing to give proper credit to co-inventors could pose a legal problem for Moderna.

“Someone Moderna sues for patent infringement could defend on the ground that Moderna deliberately misrepresented who the inventors are,” Mark Lemley, a patent expert at Stanford Law School, observed in a recent blog post.

The anti-vaccine movement has a new conspiracy theory about Pfizer’s COVID-19 shot. Don’t believe them.

The role of government science and funding in medical advances has consistently been underplayed, as Public Citizen says, depriving taxpayers of some of the benefits of their contribution. “We urge you to publicly reclaim the foundational role of the NIH,” the advocacy group said in a Nov. 2 letter to Collins.

The dispute underscores the complexity of scientific collaboration. That’s especially true of drug and vaccine development, in which years of promising laboratory research can be confounded by obstacles that emerge when a product is actually subjected to human trials.

“This whole dispute is about what exactly the NIH scientists contributed,” says Michael Carrier, a patent law expert at Rutgers University.

Inside NIH, there is no question that its scientists’ contributions were indispensable to the vaccine’s development. In early January, according to an account published in an internal NIH blog, Graham and Corbett built on their long-existing research into mRNA technologies and “quickly mapped out a plan to begin experiments, assigned roles to team members, and went to work designing an antigen — in this case, a copy of the spike protein found on the surface of the COVID-19 virus, which it uses to infect cells.”

For years, the NIH says, they had worked with “their partners at Moderna [to] perfect a method to coax the body to manufacture antigens via messenger RNA.” Among the crucial breakthroughs at NIH was a way of designing the vaccine to make it effective at blocking infections by coronaviruses such as the microbe that causes COVID-19.

“We even knew based on my lab notebooks what doses would work in animals, what exact construct to design, vaccine schedule, etc., etc.,” Corbett tweeted in mid-January.

Moderna acknowledges that NIH scientists contributed to the underlying mRNA technology, but not to the crucial step that applied it to COVID-19.

“The mRNA sequence was selected exclusively by Moderna scientists using Moderna’s technology and without input of NIAID scientists, who were not even aware of the mRNA sequence until after the patent application had already been filed,” Moderna says. “Therefore, only our scientists can be listed as the inventors on these claims.”

The question is whether the government can reclaim its stature as a fount of scientific innovation, as Public Citizen advocates. Co-inventor credit would help to “significantly bolster the public’s understanding of the critical role played by federal scientists in the invention and development of the NIH-Moderna vaccine.”

Moderna may be correct in asserting that NIH scientists didn’t participate in the last few steps that made the vaccine a reality. But it’s certainly true that without the government’s participation, Moderna would not have achieved a marketable product.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.