Coronavirus Today: All about Omicron

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, Nov. 30. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

Thanksgiving weekend was supposed to be a joyful time for hanging out with family and friends, watching football, getting serious about holiday shopping and perhaps baking cookies. But some of that joy got sucked away by the emergence of the Omicron variant.

While Americans were carving turkeys Thursday, scientists in South Africa announced that they had detected a new coronavirus variant with dozens of mutations in its genome. More than 30 of those mutations affect the all-important spike protein, upon which the virus relies to latch to the cells it seeks to infect. As if that weren’t daunting enough, several of Omicron’s mutations have been found in other variants that have worrisome properties, such as the ability to evade coronavirus antibodies produced by the immune system.

The discovery of Omicron coincided with a dramatic surge of coronavirus infections in South Africa. In the week before the announcement, the country logged just over 200 new confirmed infections each day. By Wednesday, the figure had vaulted past 1,200; by Thursday it had doubled again, to 2,465.

Health Minister Joe Phaahla said it appeared that the new variant was responsible for the exponential rise in new cases, though other scientists said it was possible that conditions were ripe for a surge, and Omicron just happened to be the version of the virus that got passed around.

Either way, the prospect of a new coronavirus that makes the Delta variant look tame was enough to prompt many countries — including the United Kingdom, Canada, Israel, Russia and members of the European Union — to restrict incoming travel from places known to have Omicron cases. In the U.S., President Biden issued a declaration to bar most visitors from South Africa, Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia and Zimbabwe for a two-week period that began Monday.

People infected with the Omicron variant have been identified in the U.K., Belgium, Hong Kong, Japan, Israel and Canada. The Netherlands revealed Tuesday that it had confirmed the presence of the variant in test samples taken as early as Nov. 19, nearly a week before the announcement in South Africa.

So far, Omicron has not been detected in the U.S., but Biden doesn’t expect that to last.

“Sooner or later, we’re going to see cases of this new variant here,” the president said Monday. “We’ll have to face this new threat just like we’ve faced those that have come before it.”

Some public health experts — and even the World Health Organization — have criticized travel bans for having very little upside while serving to punish countries that did the right thing by alerting the public about their Omicron cases. But Biden said the U.S. ban would give America’s 47 million unvaccinated adults more time to get their first COVID-19 shot. Additionally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention strengthened its endorsement of booster shots, saying that all adults should get an extra dose as soon as they are eligible to do so.

Omicron is forcing Biden and his top health officials to walk a fine line. On one hand, they want the American public to have confidence that they’re prepared to meet a serious threat; on the other, they don’t want people to panic. They’re also keenly aware that however necessary it may be to keep up with coronavirus prevention measures (such as wearing face masks), they’re likely to face resistance from a fed-up public.

Unfortunately, it will take weeks to months for scientists to understand just how dangerous Omicron truly is. In the worst-case scenario, the variant would spread more readily than Delta, blow past the protections offered by medicines and vaccines and cause more severe disease that leads to a higher death rate. In the best-case scenario, Omicron would turn out to be fast-spreading yet relatively benign, leaving millions of recovered victims with some valuable immunity.

Only time will tell where on that spectrum we’ll land. The first clues may come from labs where microbiologists, immunologists and genetic scientists are subjecting Omicron specimens to a battery of tests designed to measure its resistance to vaccines and medicines, along with its ability to replicate and spread. That work will take a few weeks at least.

It will take a little longer for contact-tracing teams and epidemiologists to gather and examine real-world data, to see how quickly Omicron spreads outside of South Africa and how its victims fare. Then mathematical modelers will put it all together to make forecasts of likely outcomes.

There are plenty of wild cards that will make this a lot less straightforward than it might seem — chief among them the fact that members of the public have a wide range of immunity, depending on their vaccination status, whether they’ve weathered a past infection and how recently their immune system was tuned up.

Tulio de Oliveira, the South African geneticist who led the team that identified the Omicron variant, said scientists have rolled up their sleeves and are hard at work.

“The next weeks are so crucial,” he said.

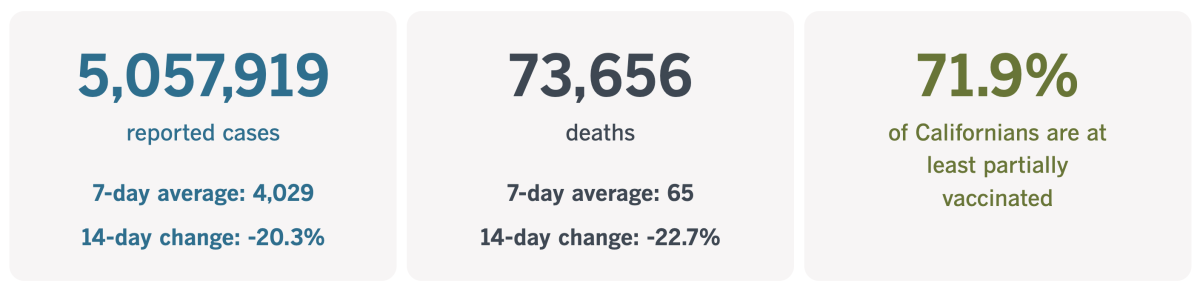

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 4:00 p.m. on Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Are vaccine hoarders to blame for Omicron?

Two years into the global outbreak, no one is happy to see Omicron come along and threaten to drag us back to square one. But there must be some folks who saw the news and were tempted to say, “I told you so.”

The people I’m talking about are the ones who’ve been calling attention for months to the vast inequities in the way COVID-19 vaccines are distributed around the globe. Overall, 54.4% of the world’s population has received at least one dose of a vaccine, and more than 31 million doses are being administered each day, according to Our World in Data. But in low-income countries, only 5.9% of people are at least partially vaccinated.

While 69.2% of U.S. residents have received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, only 24% of those in South Africa have. In the United Kingdom, 74.7% of people are partially or fully vaccinated, compared with 19.5% in Mozambique. South Korea has at least partially vaccinated 82.9% of its people; in Malawi, the figure is 5.8%.

With so many people lacking any vaccine protection, the wily coronavirus has plenty of opportunity to keep spreading — and each time it does so, it has the potential to develop new mutations. If those mutations give the virus a competitive advantage, they’re bound to spread. And once they’re on the loose, they could wind up anywhere.

“With this level of vaccine inequality, variants like Omicron are completely predictable,” Matthew Kavanagh, director of the Global Health Policy and Politics Initiative at Georgetown’s O’Neill Institute, told my colleague Emily Baumgaertner. “Boosters and travel bans will not protect Americans. We will continue to live in fear until we fix the vaccine inequalities.”

As Baumgaertner points out, in Nigeria and Ethiopia, the two most populous countries on the African continent, less than 2% of the population is fully vaccinated. Until things change, the continued emergence of new variants is all but inevitable.

Is greed to blame? In part, yes.

South Africa, India and dozens of other developing countries have called for vaccine patents to be suspended temporarily so that more countries can produce their own vaccine instead of remaining dependent on limited — and expensive — supplies from abroad. Biden has offered support for this idea, though the U.S. hasn’t done much to promote it.

The European Union opposes such a waiver, citing a fear that it would discourage pharmaceutical companies from investing in new vaccines and other medicines. The drug companies themselves agree.

Rich nations have also been somewhat stingy with their investments in COVAX, the World Health Organization initiative to get vaccines to low-income countries.

But COVAX has faced other kinds of setbacks. India is a prime manufacturer of vaccines for COVAX, but the rise of the Delta variant there prompted the country to keep doses for itself. All in all, COVAX is on track to deliver only about one-third of the nearly 500 million doses it had expected to distribute by the end of the year.

Omicron’s emergence may look like a clear sign of what can go wrong when wealthy countries hoard vaccines, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll have a change of heart. Indeed, some health experts fear the opposite — that because of Omicron, rich countries will cling more tightly to their supply (and use some of it for booster shots).

Some experts challenged the idea that stockpiling vaccines to use as boosters had much to do with Omicron’s arrival. Michael Osterholm, a University of Minnesota epidemiologist and former member of Biden’s COVID-19 advisory board, says there are many obstacles to carrying out a vaccination campaign in a developing country.

Even if supply weren’t an issue, it’s extremely difficult to get shots to remote areas. Some vaccines require refrigerated transport, which has been tricky even in the U.S. They also depend on having a network of health workers, which isn’t available everywhere. And as Americans have learned, it’s hard to persuade vaccine skeptics that the shots are good for them, Osterholm said.

Regardless of the degree of difficulty, one thing is clear: The more unvaccinated people there are, the higher the odds that new variants will emerge.

“What you see here is that, while so many people around the world are done with this pandemic, the virus isn’t done with us,” Osterholm said.

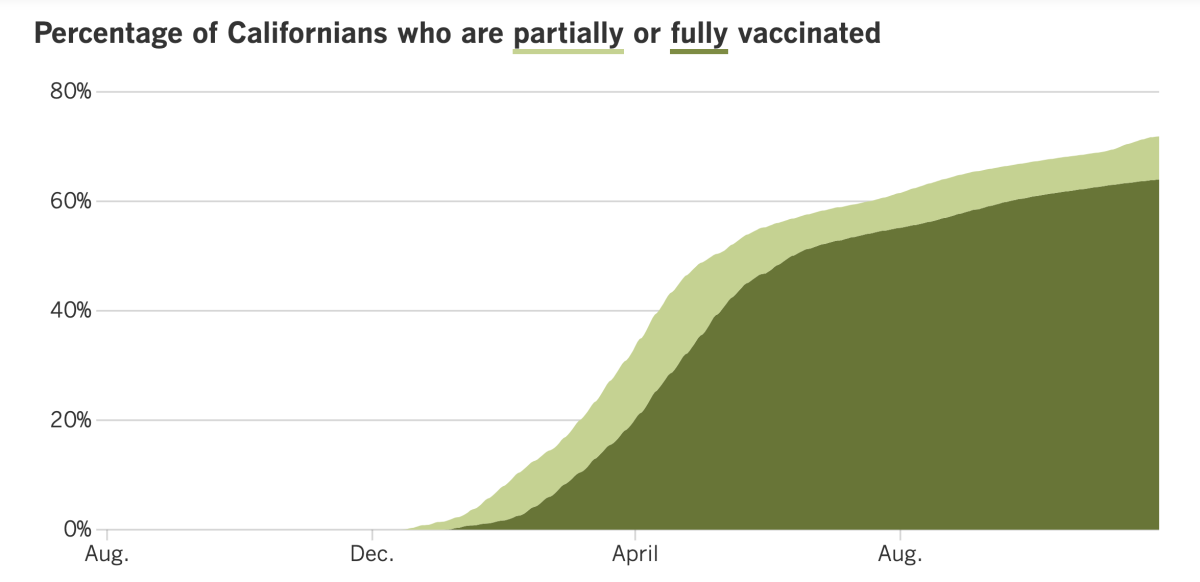

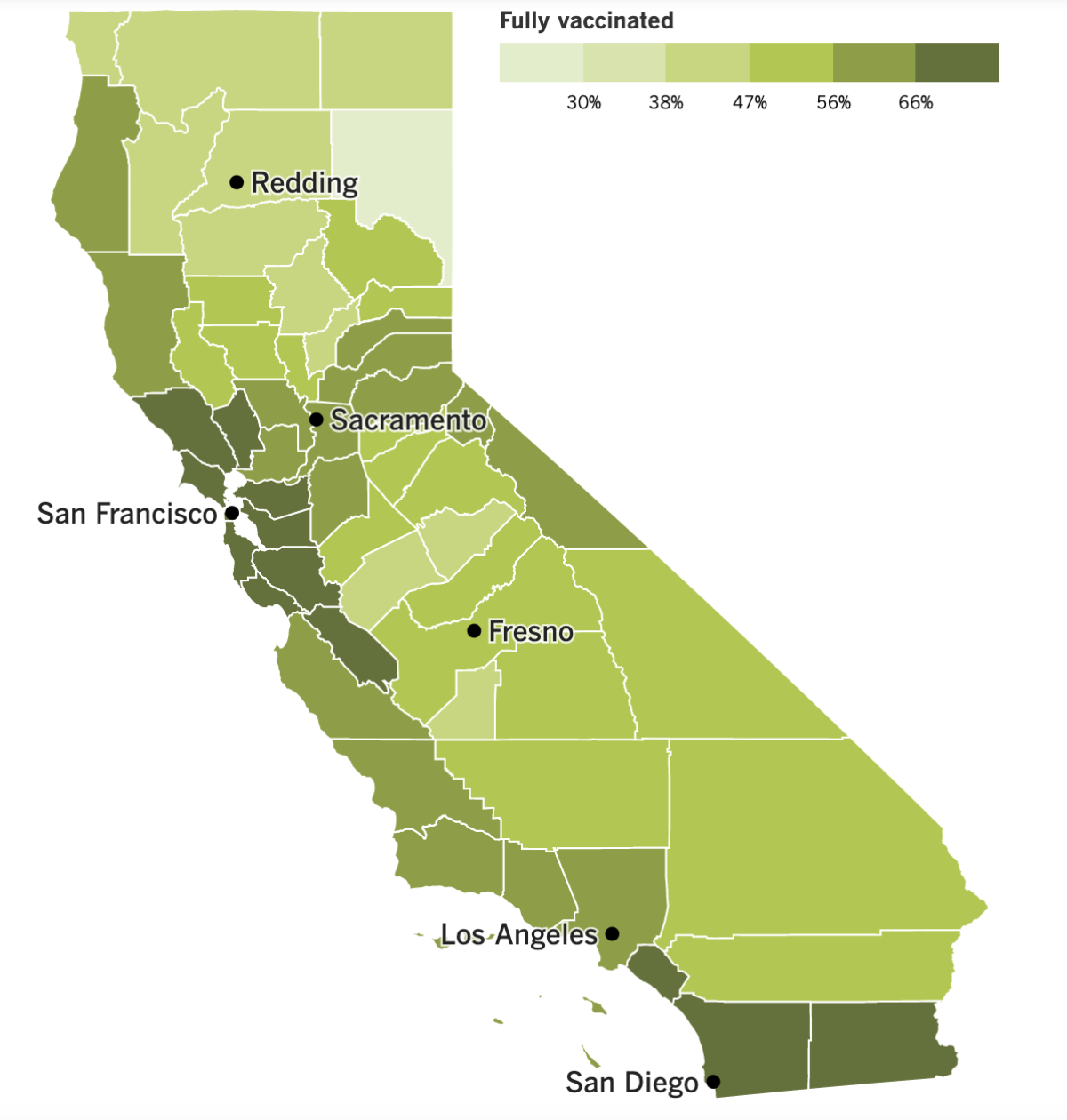

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

Remember when Merck & Co. announced it had developed a pill for COVID-19 that people could take at home, and that — when taken by newly diagnosed patients at high risk of becoming seriously ill — it cut the risk of severe disease and death in half? Those results were based on preliminary results from its clinical trial, and they were revised downward on Friday. Now Merck says the drug, called molnupiravir, reduced the risk of hospitalization and death by 30%.

That update took some of the shine off the pill. On Tuesday, it went before a panel of independent advisors to the Food and Drug Administration and was narrowly endorsed for emergency-use authorization.

After a day of presentations, 13 of the panel members decided that the drug’s modest benefits outweighed its risks, while 10 concluded it didn’t. Among those risks: Molnupiravir may cause birth defects if used by pregnant women. Also, the drug thwarts the coronavirus by inserting tiny errors into its genome that prevent it from reproducing; this raised concerns that it could spur the development of new variants.

On the other side of the ledger, the FDA advisors grappled with the fact that the drug’s upsides were less than they initially appeared. All of the people in the clinical trial were unvaccinated, and data from study participants who had immunity from a past infection suggest the pill would offer little benefit to people who are vaccinated.

Some advisors who endorsed the pill said its availability should be limited to certain populations of patients. A few suggested that if the pill wins emergency-use authorization, it could be revoked later if a better alternative comes along. The FDA is already reviewing a similar COVID-19 pill made by Pfizer.

The agency is not required to follow the advisory panel’s advice. A decision is expected before the end of the year.

Meanwhile, a small study that measured the protective value of booster shots found that people who got two doses of an mRNA vaccine and followed up with a booster about eight months later saw their levels of neutralizing antibodies skyrocket.

In 33 people, the median level of these antibodies was found to be 23 times higher a week after getting a booster shot than it had been right before that third dose. It was also three times higher than the median level measured in another group of people who were tested shortly after they became fully vaccinated.

Compared to unvaccinated people, those who received a booster had 53 times as many neutralizing antibodies. And even compared to those who had weathered a coronavirus infection and were fully vaccinated, the boosted group’s antibody level was 68% higher.

Scientists said they suspect those high levels of neutralizing antibodies will translate into longer-lasting immunity.

Speaking of booster shots, data from the L.A. County Department of Public Health show that residents of poor neighborhoods are significantly less likely than people who live in other areas to have received a booster shot. It’s yet another COVID-19 disparity, and officials say it could make already hard-hit communities more vulnerable if another surge materializes this winter.

In South L.A., the eastern San Fernando Valley, El Monte and other areas of the county rated by the California Healthy Places Index as high need, only 6.9% of people who were eligible for a booster shot had received one as of Nov. 11. Contrast that with the 12.6% of residents in wealthier areas.

In addition to erasing that gap, L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said it was important to increase booster uptake for all residents, considering the “mounting data showing that vaccine efficacy is waning over time and that boosters reduce the risk of COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths among adults of all ages.”

In other local news, it’s been three weeks since Los Angeles implemented its ordinance requiring business to check the vaccination status of patrons before serving them indoors. As of Monday, the city is enforcing its requirement.

That means restaurants, coffee houses, gyms, museums, movie theaters, salons and other indoor venues can receive a warning if they’re caught letting customers inside without asking to see proof of vaccination and checking it against a photo ID. If they get caught again, they’ll be hit with a $1,000 fine. Subsequent violations can set businesses back as much as $5,000.

Customers who aren’t vaccinated — or say they are but can’t prove it — are allowed to enter a business briefly to use the restroom or pick up a takeout order, as long as they’re wearing a mask.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: What should I do to protect myself against Omicron?

The answer is easy: The same thing you should do to protect yourself against Delta or any other coronavirus variant.

That means getting a COVID-19 vaccine if you haven’t already. If you’re eligible for a booster shot, you should get that, too. Indeed, the threat posed by Omicron — which has yet to be detected on U.S. soil — prompted CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky to renew and strengthen the agency’s recommendation for all fully vaccinated adults to get a booster as long as the appropriate amount of time has passed (six months since the second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna vaccine, or two months since the single dose of Johnson & Johnson).

Beyond needles, the CDC recommends wearing a face mask in indoor public spaces if the level of viral transmission in your area is “substantial” or “high.” That currently describes most of Southern California; the only exceptions are Orange and Ventura counties, where transmission is “moderate.”

In Los Angeles County, masks that cover the nose and mouth are required for everyone in indoor public spaces as well as on public transport. The mask mandate also extends to large outdoor events. Physical distancing is encouraged, as is frequent hand-washing.

The California Department of Public Health encourages people to get tested for a coronavirus infection right away if they experience COVID-19 symptoms. Testing is free; you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255 or 211.

If you feel sick, stay home, state and county health officials agree. L.A. County also reminds you to quarantine if you’re unvaccinated and have been exposed to someone with a confirmed case of COVID-19, even if you have no symptoms yourself. Those who are vaccinated need to quarantine after exposure only if they develop symptoms of COVID-19.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to find info: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.