Europe, already beset by Delta surges, now confronts Omicron

PARIS — Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic nearly two years ago, Europe has notched up plenty of unhappy distinctions.

The continent saw the world’s first massive wave of COVID-19 fatalities in the early months of the outbreak. The European Union, although made up of some of the world’s most advanced democracies, got off to a slow start on vaccine rollouts earlier this year.

And a hard core of vaccine resistance, often tied to far-right populism, helped set the stage for a virulent fourth wave of infections now raging across Europe, triggering stringent lockdowns whose like hadn’t been seen for months.

Now comes Omicron, and Europe once again finds itself in the coronavirus crosshairs.

Greece is making vaccines mandatory for over-60s. A woman who fled a Dutch quarantine hotel was arrested as she and her partner tried to hop a flight to Spain. A man pinpointed as having Italy’s first known case of Omicron had infected five family members by the time his illness was detected.

As the variant hopscotches the globe, disproportionate numbers of European countries — more than a dozen in all, from Sweden and Denmark in the north to Spain and Italy in the south — have acknowledged finding Omicron within their borders. Those countries with reported cases include Europe’s biggest economies: Germany, Britain and France.

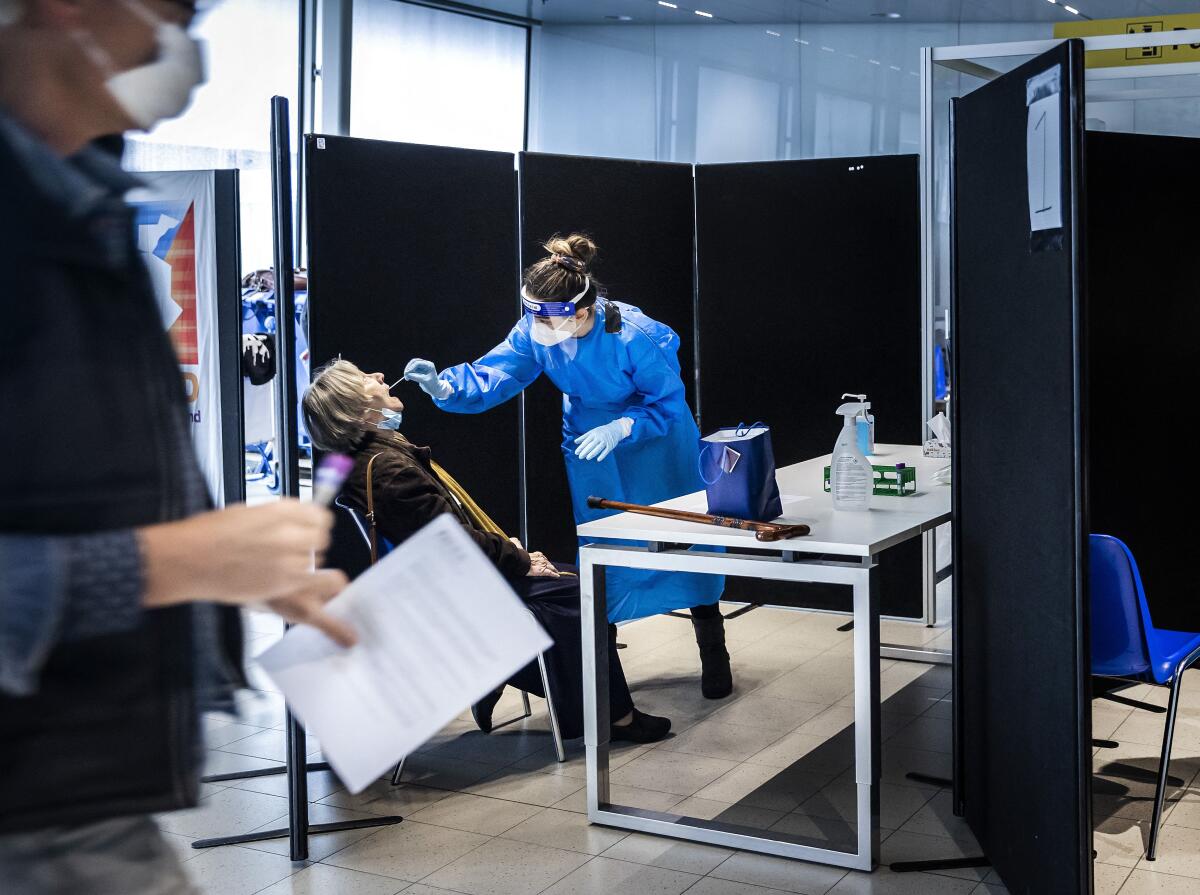

And it turns out Omicron isn’t exactly a newcomer. The Netherlands said Tuesday that it had confirmed the presence of the variant in Dutch test samples taken as early as Nov. 19 — well before South Africa first announced its detection last week. Experts believe it is already in wide circulation internationally.

All this has contributed to an enveloping sense of gloom and frustration across the continent as financial markets shudder, politicians ponder unpopular restrictive measures, and hopes for a robust return of festive year-end holiday celebrations are dashed.

In a babel of tongues, ordinary Europeans vented their pandemic fatigue.

“We seem to have gone back two years,” said Benoit Dalenne, a 45-year-old Frenchman who lives near the northern city of Lille. “We are feeling blue — as though everything we have done was not of much use.”

“People are in a bad mood,” said furloughed flight attendant Ana Maria Brito, who has been volunteering at a Berlin vaccination center. She said security personnel at the center routinely intercede in shouting matches and belligerent outbursts, usually sparked by vaccine-hesitant individuals angry over feeling pressured to get inoculated.

Near Rome’s Baroque Trevi Fountain, newsstand proprietor Maria Adele Chenet, 75, wasn’t sure she could withstand more setbacks.

“Another lockdown means I’d close down for good,” she said.

A few sought to find some semblance of levity amid the general despondency. In France, internet wags noted the resemblance between the variant’s name and that of President Emmanuel Macron, with some reporting that autocorrect functions resulted in virus-related developments being rendered as “Oh Macron.”

Even before Omicron’s unwelcome arrival, countries across Europe had been reviving former pandemic-fighting measures, pages torn from a tattered playbook.

England reimposed mandatory face masking in stores and on public transit, and a rule took effect Tuesday requiring travelers arriving in Britain to be tested for the virus and self-isolate until they have a negative result.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson said the new measures were intended to buy time to ramp up efforts against the variant, including an expansion of its booster program.

Some governments have put an emphasis on trying to fence out the variant — a strategy many experts believe will have only limited effectiveness in the face of Omicron’s already existing footholds.

Switzerland announced that beginning Wednesday, travelers arriving from Canada, Japan, Portugal and Niger — all venues where Omricon cases have popped up — will need to quarantine for 10 days, even after presenting a negative COVID-19 test. Swiss authorities, like many governments across Europe, had already banned flights from seven countries in southern Africa.

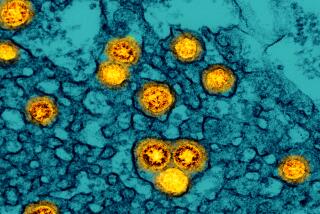

Part of the dread over Omicron is that so little is known about it — its ability to evade vaccine defenses, its degree of transmissibility, and how severe is the illness it causes.

“It’s going to take another two or three weeks to see how it develops, and understand it,” Christian Drosten, a leading German virologist and government adviser, told ZDF television. “We can’t say at all how it will impact us.”

In much of Europe, ongoing havoc from the Delta variant — which is highly contagious, and especially dangerous for the unvaccinated — is still very much at the forefront, stressing healthcare systems and generating caseloads comparable to the pandemic’s dark early days.

“We must not mistake the enemy — for the moment it is the Delta variant,” Arnaud Fontanet, a French epidemiologist and member of an advisory board to the government, said on France Inter radio. “Let’s focus on our first fight; we’ll keep Omicron for later.”

Olivier Veran, France’s health minister, told parliamentarians on Tuesday that new infections over the past 24 hours had hit 47,000 — the highest one-day tally since April, when the pandemic was raging.

Meanwhile, Germany’s coronavirus toll this week passed a bleak threshold of 100,000. A success story early in the outbreak, the country is in the midst of a frightening surge in new infections and hospitalizations, even before Omicron has had a chance to take hold.

Germany’s worsening coronavirus picture has prompted stricter public health measures, with even tighter ones being contemplated. People now need to have proof of vaccination or recovery from the virus, or a negative test, to access public transport, shops, restaurants, bars and clubs. Even traditional Christmas markets are curtailed for the second winter in a row.

“We’ve got to pull the emergency brake now,” Helge Braun, the chief of staff to outgoing Chancellor Angela Merkel, said in a newspaper interview. “We’ve reached a situation in Germany that we were always trying to prevent — our healthcare system has become overwhelmed in some regions.”

Record infection rates are also plaguing the Netherlands, and health authorities are struggling to find enough room in intensive-care wards for COVID patients. The country is less than a week into an emergency regimen that has included stores, bars and restaurants closing down for the night at 5 p.m. and people being told to work from home.

Italy, among the hardest hit countries when the pandemic began, has fared a little better. The country’s vaccine “passport” — the so-called Green Pass, introduced over the summer for restaurants, cinemas, museums and sporting events, and extended to the workplace in October — is credited with helping stem infections recent months, although contagion is again rising.

In Britain, where Johnson’s government rolled out a booster expansion program with some fanfare this week — everyone over 18 is now eligible — health authorities acknowledged that Omicron’s emergence echoed a familiar pandemic pattern: much-touted progress can be swiftly undercut by events.

“Just as the vaccination program has shifted the odds in our favor, a worrying new variant has always had the opportunity to shift them back,” Health Secretary Sajid Javid told the House of Commons on Monday. “In this race between the vaccines and the virus, the new variant may have given the virus extra legs.”

Special correspondent El-Faizy reported from Paris and Times staff writer King from Washington. Special correspondents Erik Kirschbaum in Berlin, Christina Boyle in London and Tom Kington in Rome contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.