Coronavirus Today: The pandemic one year in

Good evening. I’m Thuc Nhi Nguyen, and it’s Thursday, March 11. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

What were you doing one year ago today, dear reader?

I went to a college basketball practice in the morning. I stood within arm’s length of a coach after the team’s workout and brought up this new virus people were talking about. The coach, focused on the upcoming NCAA tournament, didn’t want to worry.

The World Health Organization declared it a pandemic today, I said. Neither of us truly knew what that meant.

That day seems like it was from another life now.

We have not all suffered equally since March 11, 2020, but we have all suffered, my colleagues Deborah Netburn and Soumya Karlamangla remind us.

More than 55,000 Californians have died of COVID-19 in the last year. Their families have struggled to memorialize them as funerals and other gatherings were restricted. The sheer weight of so many lives lost moved Los Angeles County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer to tears multiple times during news briefings.

Even those of us lucky enough to keep our jobs and our health have paid a price. We saved lives by complying with California’s strict stay-at-home orders and mask mandates. But we lost a sense of community and felt isolated and alone.

The trade-off almost became too much for Leslie Grossman, 49, an actress and third-generation Angeleno.

“I’m well aware that L.A. is not a perfect city, but this was the first time I felt like I don’t know if I can live here anymore,” she said. “There is this aspect of feeling like the city is on fire and there’s nothing we can do except don’t leave your home.”

The suffering wasn’t limited to a once-in-a-century pandemic. Protesters filled streets after George Floyd died under a police officer’s knee. Some of the largest wildfires in California’s recorded history made it difficult to go outside, taking away one of the few things the pandemic allowed us to have. An insurrectionist mob stormed the U.S. Capitol. Anti-Asian hate crimes rose. Meanwhile, the virus itself was changing, threatening to extend its reign for years to come with different variants.

Experts like Roxane Cohen Silver, a professor at UC Irvine who studies how people respond to collective crises, have a name for this type of continuous cluster of emotions: cascading collective trauma. “This event has been continued, it’s been chronic, it’s been escalating, and it has morphed from one traumatic event to another to another,” Silver said.

After getting knocked down so many times, we’re starting to find our feet again. Vaccines bolster our hopes for a life after the pandemic when hugs return, friends can gather at a bar for drinks and whole tables are full for family dinners. There won’t be a mask in sight. You’ll be able to see people smile again.

By the numbers

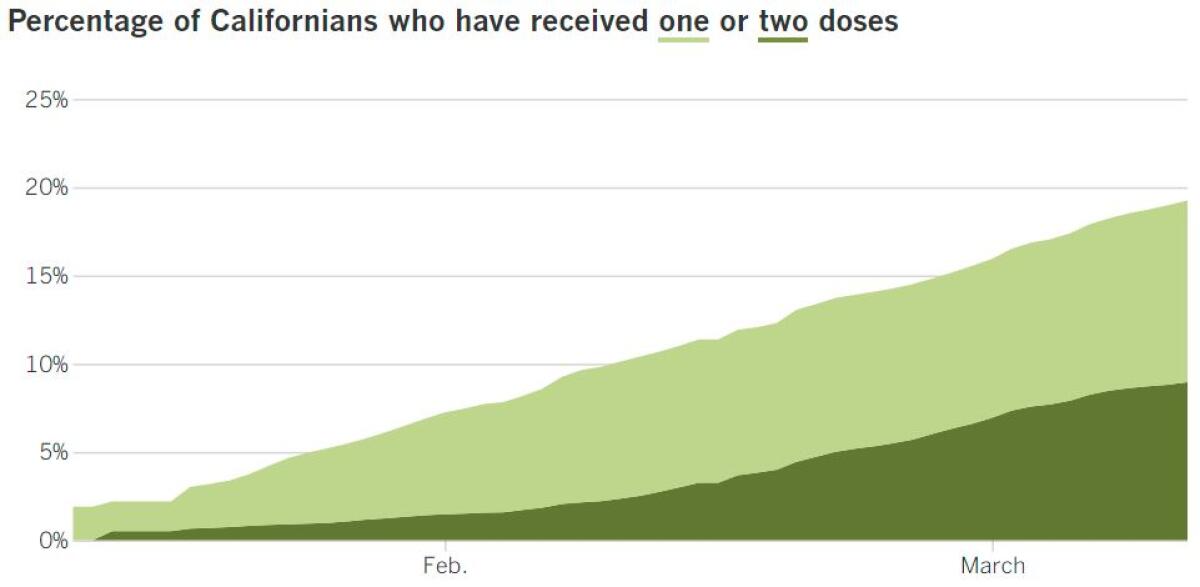

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 6:07 p.m. Thursday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Across California

Being a teenager is hard enough. Then the pandemic canceled proms, graduations and almost every other rite of passage high schoolers usually enjoy.

The lost year was especially difficult for high school athletes, reports my colleague Eric Sondheimer. (As an aside, if you’re a fan of high school sports, please subscribe to Sondheimer’s Prep Rally newsletter, which launches this month.) Unlike for college athletes who can apply for extra eligibility, there are no waivers for fifth or sixth years in high school. These student athletes lost cherished opportunities to compete alongside their friends, and some may have missed out on ways to earn college scholarships.

Without sports as an outlet, concern for the mental health of athletes grew. Some parents worried their kids were becoming depressed. Coaches reported difficulties motivating players to focus on their studies.

Athletes like Jennifer Soto, a Downey High lacrosse player, and Mekhi Evans-Bey, a football player from Culver City, saw the pandemic’s wrath up close. Evans-Bey became the caregiver for his mother after she fell ill. It changed him, he said, but she recovered. Soto’s foster father did not; he died of COVID-19 in March.

Indeed, COVID-19 has become the leading cause of death in L.A. County, claiming more than twice as many victims as the disease that previously held the top spot.

Before the pandemic, coronary heart disease was the county’s leading cause of death. Now the 11,000 victims of heart disease during the last year pale in comparison to the more than 22,000 deaths caused by COVID-19.

With case rates dropping since the holiday surge that accounted for most of L.A.’s COVID-19 deaths, the county is preparing for restaurants, gyms, museums and movie theaters to open possibly as early as Monday, my colleagues report.

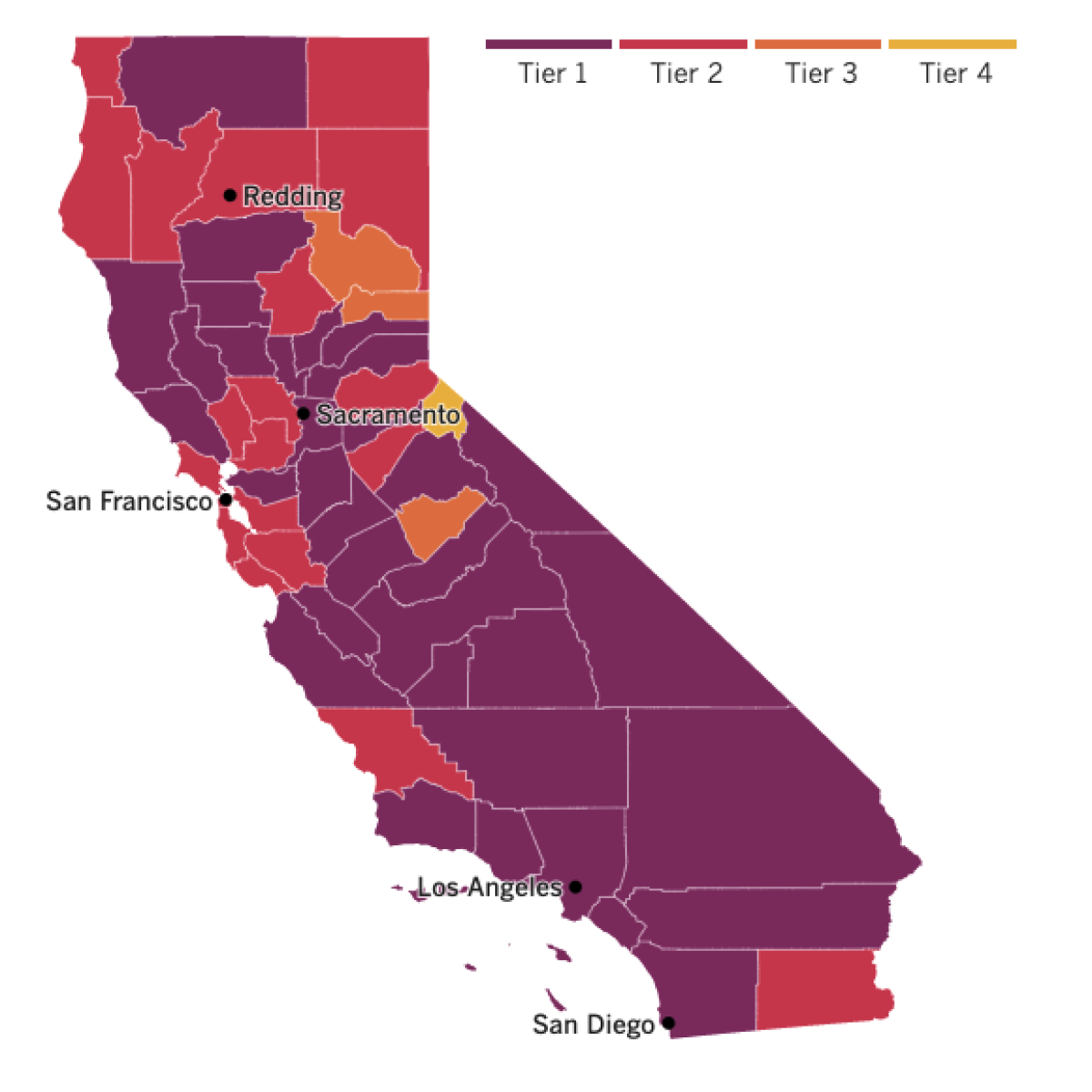

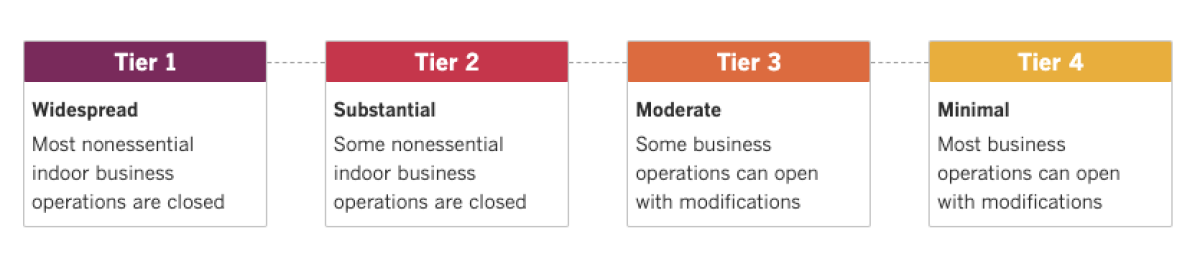

County officials are still waiting for the state to administer 2 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine to its most disadvantaged communities, but that could happen by Friday. If it does, then the state would immediately relax the requirements to move out of the most restrictive tier, purple, and into the red tier. L.A. County’s new public health order could go into effect as early as Monday morning.

Among other things, the new order would allow indoor restaurant dining at 25% capacity, marking the first time in more than eight months that restaurants could serve customers indoors. No table can seat more than six people, and they all have to be from the same household. In addition, tables have to be at least eight feet apart.

Private gatherings will be allowed for people from up to three separate households as long as masks are worn and distancing is maintained. People who are fully vaccinated will have the option of gathering in small numbers indoors with others who are fully vaccinated without being subject to masking and distancing requirements.

Several other counties, including Orange and San Bernardino, are also in position to move into the red tier as soon as the state meets its vaccine threshold, but final decisions on how and when to open indoor businesses rests with local health departments.

Next week could be a big one not only for businesses trying to reopen but also for Californians waiting to become eligible for a COVID-19 vaccine. People with disabilities and certain underlying medical conditions can join the line starting Monday, along with people who live or work in a congregate residential setting (such as a detention center, homeless shelter or behavioral health facility) and public transit workers (including employees of commercial airlines).

The state is not requiring that eligible people present documentation of their condition. Instead, all will be required to self-attest that they meet the criteria, according to guidance the state released Thursday on the verification process. It also offered specific examples of people who would qualify for eligibility but are not explicitly listed. You can find details of who is eligible in the state’s bulletin here.

Just because a person is eligible doesn’t mean a dose will be readily available for them, however. Vaccine supplies will still be limited.

See the latest on California’s coronavirus closures and reopenings, and the metrics that inform them, with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Around the nation and the world

Masks have been lifesavers during the pandemic, but their ability to slow the virus’ transmission has come with many drawbacks. Some are minor, like temporarily fogged-up glasses. Others present bigger problems, like coming between doctors and their patients.

A new study highlighted that unfortunate side effect of universal mask-wearing and one possible way to overcome it, my colleague Amina Khan reports.

Researchers randomly assigned surgeons into one of two groups: one that wore traditional surgical masks that concealed their faces from the nose down, and another that wore equally safe masks made of transparent plastic. The surgeons wore their assigned masks while speaking to new patients, who were interviewed afterward by researchers.

When patients interacted with surgeons who wore clear masks, they were more likely to understand what the doctor was telling them and to come away from their appointment feeling that the doctor empathized with them. Ultimately, these patients were more likely to trust the physician’s decisions than were patients who spoke to surgeons wearing traditional, face-obscuring masks.

Dr. Muneera Kapadia, a colorectal surgeon at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, said the results suggest that patients who are hard of hearing rely on lip-reading more than she had realized and that silent facial cues are an important aspect of communication.

“I think we miss those things when half of the face is covered,” Kapadia said.

Health officials continue to recommend the use of face coverings even as vaccinations help bring case rates down. Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, says mask-wearing, social distancing and limits on gatherings “give us a fighting chance to get vaccine to as many people as possible” before more dangerous viral variants emerge.

Two new studies in the journal Science support her reason for concern about those variants, my colleague Melissa Healy reports.

In one of them, researchers at Oxford University studied how the virus changed as it moved from person to person. They found that when a mutation arises that makes the virus more transmissible or more virulent, it will have the potential to spread rapidly if conditions are ripe for another surge — that is, if people resume their pre-pandemic activities without taking proper precautions.

A second study examined the effects of delaying the second dose of a two-dose vaccine regimen and showed that the period between doses can be a vulnerable time. If the protection offered by the first dose is enough to affect the virus but not enough to suppress it altogether, it will put pressure on the virus to evolve a workaround. The result would be a more vaccine-resistant variant, which, ironically, could undermine efforts to end the pandemic through mass vaccination. The risk is particularly high “in places where vaccine deployment is delayed and vaccination rates are low,” the study authors wrote.

Europe, which has struggled to fuel its vaccine rollout, signed on some help Thursday when the European Medicines Agency authorized Johnson & Johnson’s one-dose COVID-19 shot. The European Union will have four vaccines available, including two-dose options from Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna and AstraZeneca.

J&J is also trying to earn emergency authorization of its vaccine in Britain and by the WHO. The company’s easier-to-administer vaccine is expected to speed up vaccination efforts, but production delays have tempered early excitement. J&J is partnering with rival pharmaceutical companies to ramp up production and deliver on promises to supply 200 million doses to the United States.

In Cambodia, the pandemic’s anniversary came with a somber milestone: the country’s first COVID-19 death.

A 50-year-old man who was infected last month while working as a driver died Thursday. Cambodia (population about 16.7 million) has confirmed only 1,163 coronavirus infections since the pandemic began, almost all in the last month. The outbreak was traced to a foreign resident who broke quarantine in a hotel and went to a nightclub in early February. The government responded by announcing a two-week closure of all public schools, movie theaters, bars and entertainment areas in the capital city. The restrictions were extended as the outbreak grew.

A luxury hotel in the capital is now being converted into a 500-room COVID-19 hospital, and authorities are enforcing a new law imposing criminal punishments for violating health rules.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: How will the COVID-19 relief package affect me?

At more than 500 pages long with a $1.9-trillion price tag, it has something for almost everyone.

Let’s start with how it could affect your bank account.

For individuals who make up to $75,000 a year and those who file as a head of household and earn less than $112,500, there is a $1,400 direct payment. People who file jointly and make less than $150,000 a year will receive $2,800. After President Biden signed the bill into law Thursday, the funds could land in your bank account as early as this weekend, according to White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki.

But the size of the direct payments drops off quickly after that. Individuals who make more than $80,000 a year, joint filers with annual incomes of $160,000 or more and heads of households earning $120,000 or more don’t qualify for a stimulus check.

Parents who meet the income limits above get an additional $1,400 for each child on their tax returns, including adult children and those with permanent disabilities who are claimed as dependents.

There is also a $300 weekly federal unemployment benefit that will last through September and supplement any state unemployment benefit.

The package also includes significant perks from a tax perspective. Instead of unemployment money counting as taxable income, the first $10,200 of unemployment compensation is tax-free this year. And the legislation boosted the existing federal child tax credit to $3,000 per child from 6 to 17 years old — $3,600 for younger children — and made it fully refundable. (That means that if credit is worth more than you owe, you’ll get a refund for the difference.)

The Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit got bumped up to $4,000 for the child-care expenses of one child, and up to $8,000 for two or more children.

For those looking for help with health insurance, the package featured the first major expansion of the Affordable Care Act since its passage 11 years ago. Now, subsidies will be calculated differently, consumers will be expected to pay less and more people will be eligible. Roughly 29 million people stand to benefit from the Obamacare changes, which will apply retroactively to Jan. 1, 2021, and last through 2022.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Keep in mind that supplies are limited, and getting one can be a challenge. Sign up for email updates, check your eligibility and, if you’re eligible, make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.