Coronavirus Today: Homelessness, hotels and public health

Good evening. I’m Thuc Nhi Nguyen, and it’s Wednesday, March 3. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

When the coronavirus began spreading in earnest last March, states issued stay-at-home orders and asked residents to stay inside, avoid large crowds and regularly wash their hands. If they were exposed to or infected with the coronavirus, they needed to quarantine or isolate in their homes immediately.

For more than half a million people in the U.S., that wasn’t an option. They were homeless, living without independent or reliable shelter.

Researchers in San Francisco found a solution, and a year later, they’ve shown the public health benefits of providing stable housing and services to those who need them most, my colleague Amina Khan reports.

In San Francisco, where more than 8,000 people experience homelessness every night and 18,000 more live in single-room occupancy hotels with shared kitchens and bathrooms, researchers welcomed homeless people with confirmed or suspected coronavirus infections into isolation and quarantine hotels. When COVID-19 symptoms were present, they were in the mild to moderate range.

At the hotels, healthcare workers provided free, around-the-clock support to guests, who were monitored through twice-a-day wellness check calls. Those with alcohol or other substance use problems were offered consultations with addiction medicine specialists via telemedicine.

Guests received hygiene kits and meals that accommodated their dietary restrictions. Those with young children were offered diapers and formula, and pets were allowed to stay on-site. The researchers also stored guests’ belongings, provided laundry services and offered $20 gift cards at the end of the stay.

About 81% of the total 1,009 guests completed the program. Those who made it through stayed an average of 13.1 days.

In sticking to the program, the hotel guests likely helped reduce the virus’ spread in San Francisco. They also helped free up limited hospital resources — including the personnel needed to attend to more seriously ill patients.

“That really helped to decompress the hospital, particularly during the early days of the pandemic, when that was really important,” said the study’s lead author Dr. Jonathan Fuchs, a physician-epidemiologist with the San Francisco Department of Public Health and UC San Francisco.

In Los Angeles, the city’s effort to shelter homeless people in hotel rooms during the pandemic didn’t deliver on its lofty goal of housing one-quarter of the nearly 60,000 people who live without permanent shelter in the county. My colleagues on the Data Desk who are tracking Project Roomkey show that 1,879 people were housed through the program as of Tuesday. The hope was to rent rooms for 15,000 people who had been identified as especially vulnerable because of their age or medical conditions.

The program was set to close by the end of March, but more federal funding from the Biden administration allowed it to continue in a scaled-down version, with three hotels staying open until at least the end of September. (Read on for more news about Project Roomkey.)

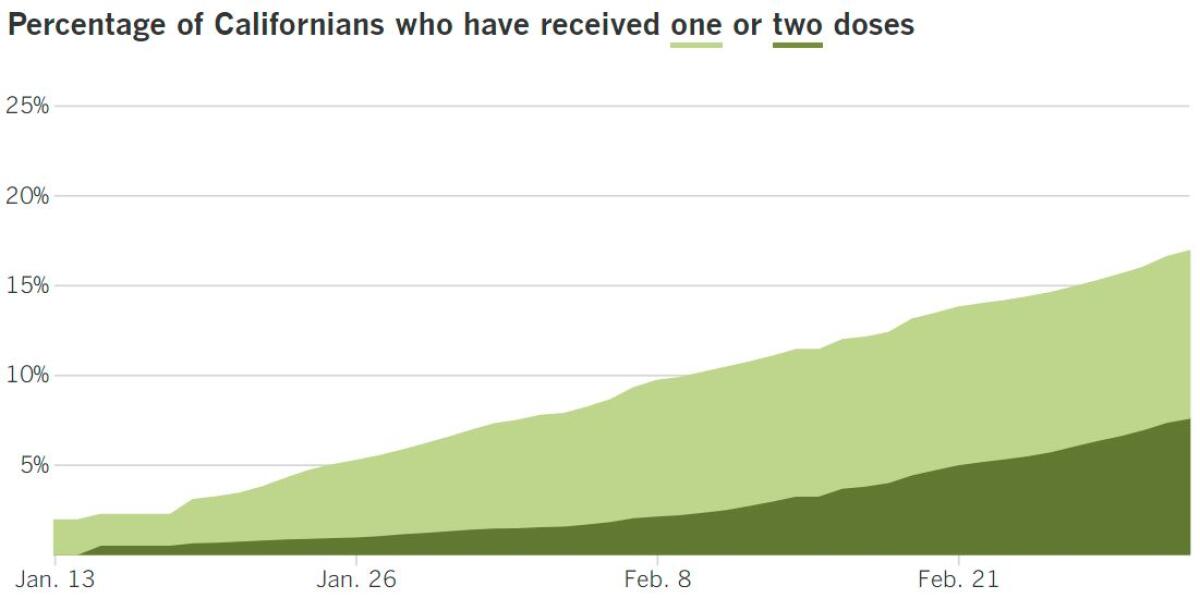

By the numbers

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 5:55 p.m. Wednesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Across California

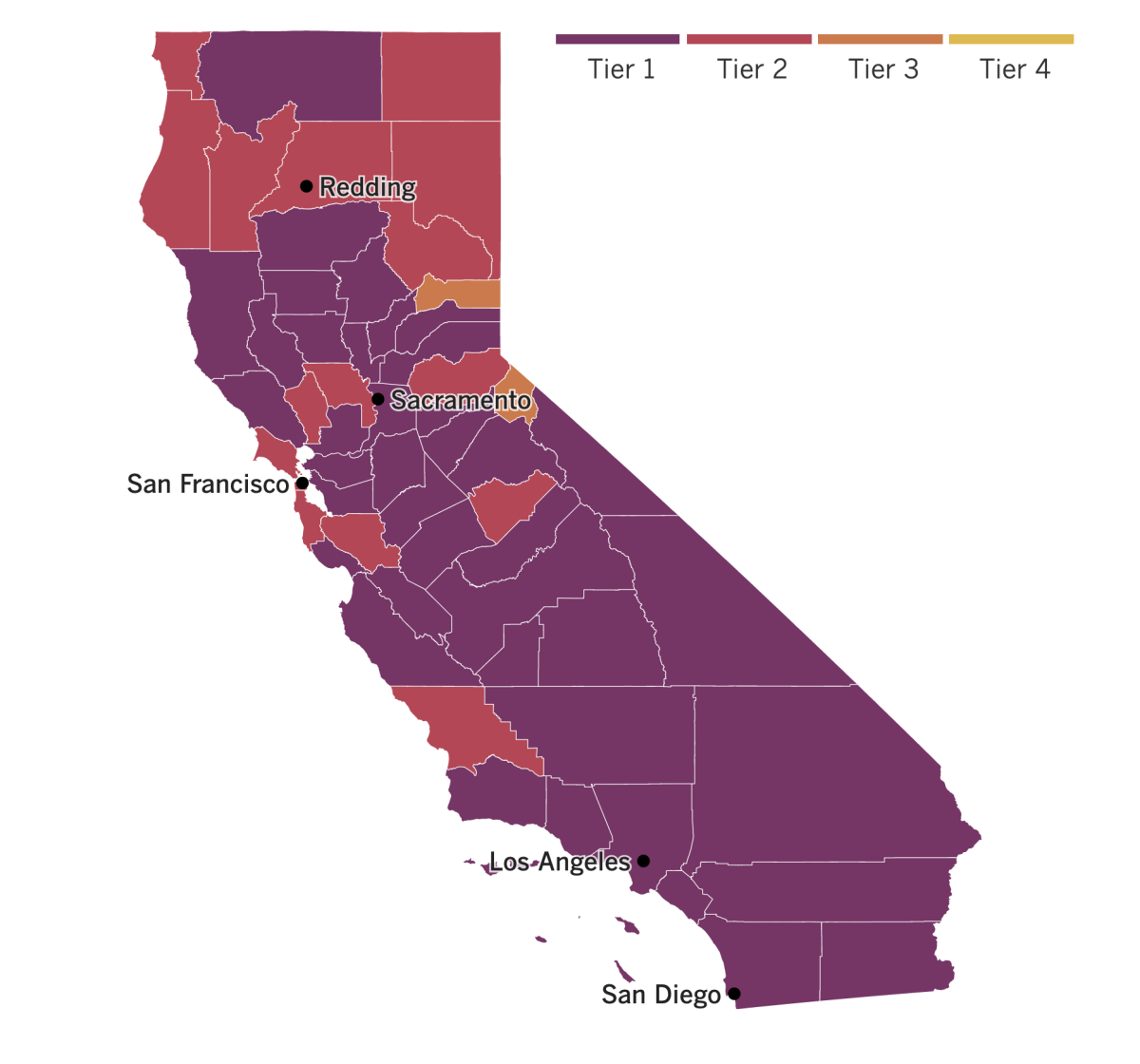

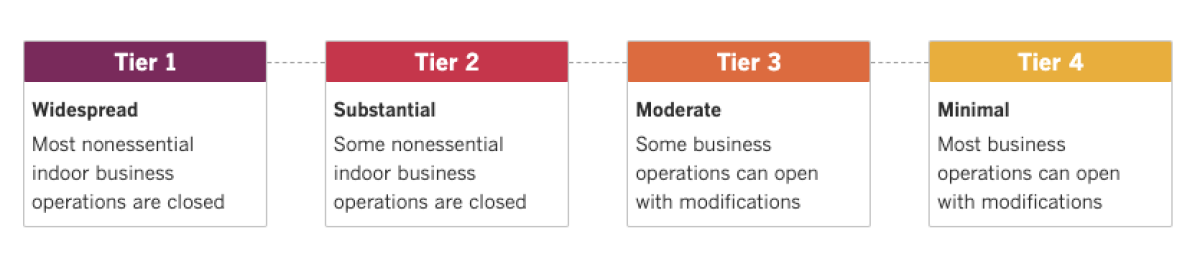

With a little less coronavirus transmission and a little more patience, L.A. and Orange counties could soon be moving into redder, freer pastures. Getting out of the purple tier, the most restrictive level of the state’s reopening plan, could happen in as soon as two weeks.

Enjoying a socially distant meal inside a restaurant or ditching your at-home workouts in favor of going to a gym may seem like small rewards for enduring months of closures that frustrated business owners and customers. But experts stress that we haven’t reached the finish line yet, my colleagues report.

“Yes, we are opening up — but that in no way means we can become complacent and start letting our guard down,” said Rita Burke, an epidemiologist at USC’s Keck School of Medicine.

The coming months remain uncertain for a variety of reasons, including the emergence of new coronavirus strains that appear to be more transmissible and show signs of being less susceptible to COVID-19 vaccines.

As long as those variants spread faster than shots can be stuck into arms, they’ll keep getting chances to mutate in ways that could make them more dangerous. That’s why experts encourage people to continue doing what finally got us to the brink of exiting the purple tier: keep wearing masks, maintain distance and limiting gatherings with people from other households.

Some states, like Texas, have lifted their mask mandates and allowed businesses to resume all indoor operations now that infections and hospitalizations are falling. But that kind of all-or-nothing approach could easily backfire.

“If we could learn from these things and practice moderation — not go straight from ‘no’ to ‘yes’ on all fronts — then maybe we can mitigate transmission,” said Dr. Shruti Gohil, associate medical director of epidemiology and infection prevention at UC Irvine. “But it’s hard. How do we message that nuance?”

In California, part of the answer is reopening indoor businesses with limits on their capacity. Counties in the red tier can let restaurants and movie theaters open indoors at 25% capacity or with up to 100 people, whichever is fewer. Gyms and dance and yoga studios can open indoors at 10% capacity, while museums, zoos and aquariums can go up to 25% capacity. Nonessential stores and libraries, which are already operating indoors at 25% capacity, can go up to 50% capacity.

Resuming indoor dining, even with strict limits, could provide a much-needed boost to struggling restaurants. Take-out and delivery orders were supposed to help keep them afloat, but some of the fees associated with these options only added insult to injury, my colleague Jenn Harris reports.

Caitlin and Daniel Cutler, owners of Ronan, an Italian restaurant on Melrose Avenue, paid $35,000 in delivery service fees in 2020. That’s one-third of a year’s rent for them. The fees ranged from 20% per order on Postmates and Uber Eats to 3% on Tock. The independent delivery companies provide restaurants with a service they wouldn’t have the resources to offer on their own, yet for many already strapped small businesses, they hurt almost as much as help.

Businesses were able to apply for help through the Paycheck Protection Program, but researchers at UCLA found disparities in how the loans were applied, my colleague Alejandra Reyes-Velarde reports. PPP money more often went to the majority-white areas of California than to majority-Latino areas, according to the study. That disparity may have been due to the fact that the loans were awarded on a first-come, first-served basis.

Larger businesses that had existing relationships with big banks were better equipped to get the loans than smaller Latino businesses with fewer ties and less knowledge about how to apply for assistance, said Rodrigo Dominguez-Villegas, director of research for the UCLA Latino Policy and Politics Initiative.

The UCLA researchers analyzed PPP funding in California by congressional district and found that of the districts that made the top 20% in terms of PPP loan dollars, none were majority-Latino.

Betty Jo Toccoli, president of the California Small Business Assn., said gaps in communication and support were the main drivers of the disparities, not race. It’s important for the association to educate legislators on the needs of small-business owners, she said, especially because many who were eligible for loans may not have applied because they didn’t think they qualified. “This was disappointing,” Toccoli said. “I think there were not simple, clear instructions.”

And speaking of federal funds to address the pandemic, my colleagues Benjamin Oreskes and Dakota Smith report that Los Angeles is owed an estimated $59 million for its Project Roomkey expenses — and that the reason the city hasn’t received any money nearly a year into the crisis is that Mayor Eric Garcetti’s administration hasn’t asked for it.

When a Project Roomkey client is put up in a hotel, the city pays the tab and then seeks reimbursement from Washington, D.C. Under former President Trump, L.A. expected to receive 75% of the money it spent. In January, President Biden signed an executive order that upped that percentage to 100% until the end of September.

Despite pressure from advocates to expand the program, Garcetti has often cited a cash flow problem as an obstacle. City Hall is facing a financial crisis and needs money to spend before it can get federal reimbursements. It can take years to get those payments, the mayor said.

The reasoning is not cutting it for advocates. “There is federal money on the table — the literal FEMA response the mayor has been begging for, and yet the city has found excuse after excuse not to take advantage of it,” said Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles attorney Shayla Myers.

See the latest on California’s coronavirus closures and reopenings, and the metrics that inform them, with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Around the nation and the world

Seeing L.A.’s freeways completely empty at 4 p.m. on a Friday last spring was like seeing a unicorn. In addition to the breezy commutes for essential workers, the rare sight of a wide-open 405 was a major sign of 2020’s impact on global greenhouse gas emissions.

With people staying home and industrial activity reduced during the pandemic, global carbon dioxide emissions fell by 2.6 billion metric tons in 2020, to 34 billion metric tons. It was a 7% drop from 2019 levels, carbon-tracking research shows.

Now experts are hoping to find ways to keep that momentum going as economies reopen and people return to their regular rhythms of life. But it won’t be easy, according to another story by Amina Khan.

She reports on a team of international researchers who determined that countries will have to continue cutting emissions by pandemic-level amounts — that is, by about 1 billion to 2 billion metric tons per year — for every year throughout the 2020s if they want to meet the climate target set by the Paris agreement in 2015. The hope was to limit global warming to less than 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels (and preferably to 1.5 degrees, if possible).

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Of course, no one wants to repeat the economic interruption brought on by the pandemic to reach those climate goals. The key, according to the researchers, is ensuring that the post-pandemic world is rebuilt with a greener economy. Among other things, that means encouraging infrastructure built upon renewable resources as opposed to investing in fossil fuels to get us moving again.

It may sound daunting, but it’s doable, said Emily Grubert, a civil and environmental engineer at Georgia Tech who was not involved in the study.

We can return to a life that feels “normal” after the pandemic — visiting with friends and family, going to our offices and dining out in restaurants, she said. However, we’ll need to make an effort to use fewer services so we use less energy — and when we do, we’ll want to make sure it comes from cleaner sources.

In Britain, health officials are reporting that their high-stakes gamble on stretching COVID-19 vaccines appears to have paid off, my colleague Melissa Healy reports.

Confronted with a new, more transmissible coronavirus strain and surging infection rates, British officials opted to spread out their limited vaccine supply by giving first doses to as many people as possible and delaying second doses until more shots were available. The hope was to provide at least some protection to more people, but the choice was met with skepticism from experts in the United States since the vaccines weren’t meant to be used that way and the unconventional protocol wasn’t tested in clinical trials.

Now, a preliminary report released by Public Health England showed that just one dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine was 60% to 70% effective at preventing symptomatic disease in people 70 and older. The protection kicked in 10 to 13 days after receiving the shot and lasted for more than six weeks.

The study authors found that a month after Brits ages 80 and over got a first dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, they were 43% less likely to be admitted to the hospital with COVID-19 than their unvaccinated peers. Even when stretching the recommended three-week timeframe between first and second doses, people ages 70 and older saw the risk of developing any type of COVID-19 symptoms reduced by 85% to 90% — a level of protection in line with that seen in clinical trials.

Another positive sign: The vaccine’s effects were undiminished by the widespread presence of the more transmissible U.K. strain, known as B.1.1.7. A report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention predicted that B.1.1.7 will become dominant in the U.S. sometime this month.

Vaccines continue to roll out around the world as more African countries received their first doses through the global Covax initiative this week.

Along with Ghana, the first country on the continent to get supplies through the program aimed at providing vaccines to low- and middle-income countries, Ivory Coast, Nigeria, Angola, Congo, Kenya and Rwanda now have the vaccine and can start inoculating their residents. Mali, Senegal, Malawi and Uganda are expected to receive doses in the coming days.

The continent has a goal to vaccinate 60% of its population to reach herd immunity, but Covax’s help alone will not provide enough doses to achieve the mark. Some countries like South Africa, the hardest-hit African nation, are pursuing additional deals or working through the African Union’s bulk-purchasing program.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: If I’ve had a bad reaction to a vaccine before, how do I know the COVID-19 vaccine is safe for me?

First, it’s important to know that any personal history with vaccines should be discussed with your doctor. They will be able to offer the most specific advice.

What doctors may ask during those conversations is whether you’ve had a severe allergic reaction to a previous dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, said Dr. Robert Kim-Farley, a professor of epidemiology and community health sciences at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health. If that is the case, the CDC does not recommend getting the second dose.

By “severe allergic reaction,” doctors aren’t referring to something like a sore arm or even a fever. They are talking about anaphylaxis, a potentially life-threatening condition whose symptoms can include a skin rash or hives, nausea, vomiting and difficulty breathing.

Anaphylactic reactions have been very rare for the COVID-19 shots. In the first 10 days of the Pfizer-BioNTech’s vaccine rollout in the United States, there were 11.1 cases per 1 million doses ,and none of them were fatal. The Moderna vaccine was associated with just 2.5 cases for every 1 million doses, according to data collected in the first three weeks of its rollout, and no one died.

For safety reasons, vaccination sites are advised to monitor people for up to 30 minutes after they receive their injections. That way, if there’s a severe allergic reaction, medical personnel can respond quickly by treating them with epinephrine.

Another topic your doctor might discuss is whether you’re allergic to any of the components used in the vaccine. Two specifically mentioned by the CDC are polyethylene glycol (PEG), a compound that makes the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines more stable, and an emulsifier called polysorbate. If you have had known reactions to any vaccine ingredient, your doctor will refer you to an allergist-immunologist, who will then determine whether its safe for you to receive the vaccine, possibly in a controlled setting.

Both PEG and polysorbate are used in other medical circumstances. For example, polysorbate appears in some Hepatitis A and DTaP (Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis) vaccines, which are common in the United States.

“Vaccines are safe and effective,” Kim-Farley said. “No vaccine is 100% safe or 100% effective. But [people] should feel confident in taking these vaccines because the benefits are going to far outweigh the risk except in unusual circumstances and most people will have experience in the past know if they had a severe reaction to one of these components.”

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Keep in mind that supplies are limited, and getting one can be a challenge. Sign up for email updates, check your eligibility and, if you’re eligible, make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.