Global carbon emissions dropped a record 7% due to COVID-19. Don’t count on it to last

The COVID-19 pandemic reduced global greenhouse gas emissions by a record 7% this year, according to new estimates released Thursday by an international group of scientists.

“We have never registered such a large change,” said Corinne Le Quéré, a professor of climate change science at the University of East Anglia in England who is part of the research team behind the Global Carbon Project.

But the reductions are probably a short-lived effect of stay-at-home orders and the resulting economic downturn, and are bound to vanish once a COVID vaccine becomes widely available and transportation and industry returns to pre-pandemic levels. For that reason, the dip in emissions is not expected to significantly slow the warming of the planet.

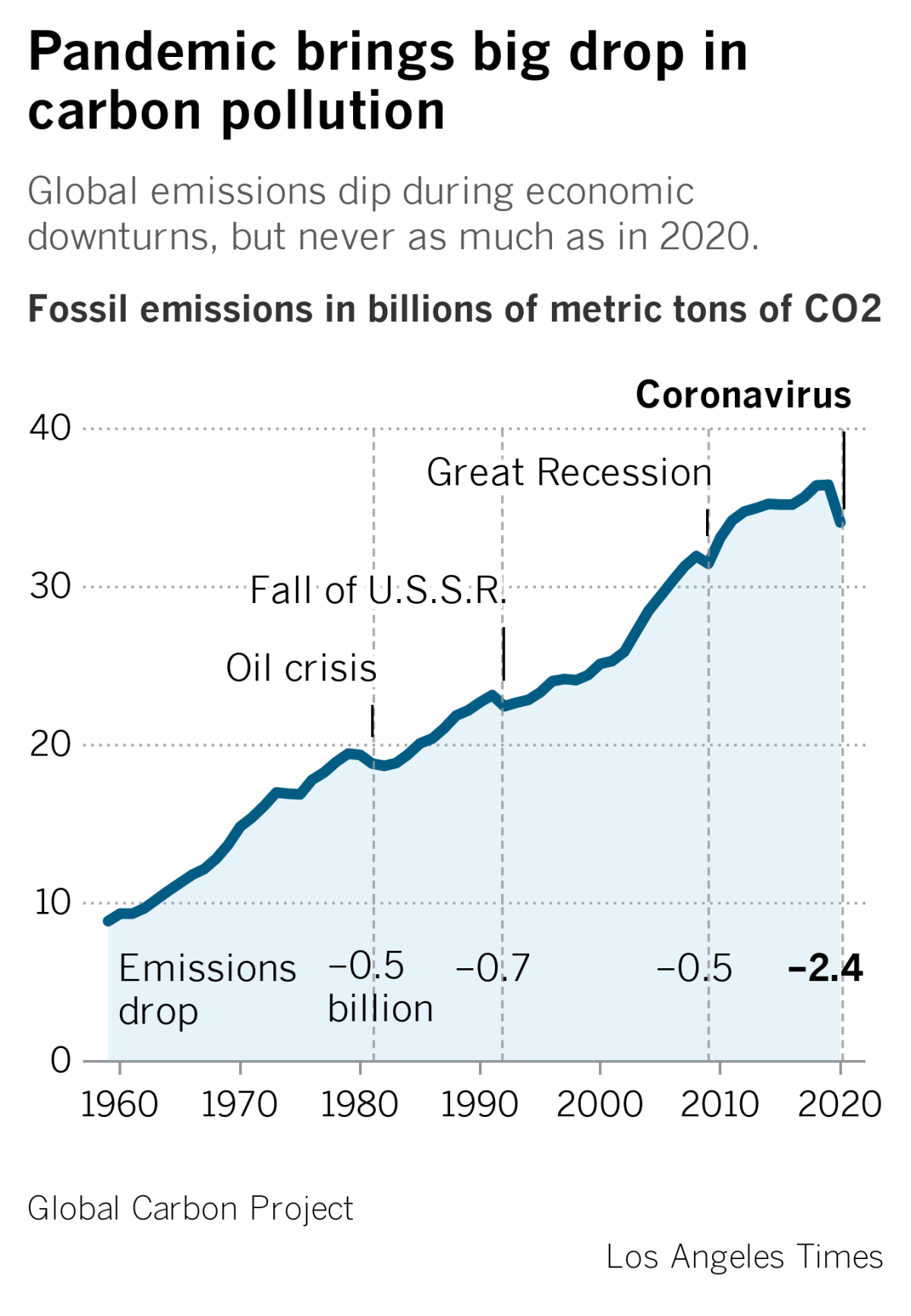

Emissions are projected to drop by 2.6 billion tons of carbon dioxide in 2020, compared with 2019, according to the analysis. That’s the greatest percentage decline in planet-warming pollution since World War II, and considerably larger than the nearly 1 billion tons reduced in 1945, according to the analysis by more than 80 researchers.

The projections were released a day after a United Nations report warned that the pandemic-caused dip in emissions will have a “negligible long-term impact on climate change” and does not alter the world’s path toward a catastrophic rise in temperatures. Warming is on track to exceed 3 degrees Celsius by the end of this century unless pollution is cut swiftly and dramatically, the U.N. found.

What this year’s emissions reductions clearly demonstrate is the scale of change needed to tackle global warming.

Adopted five years ago, the Paris climate agreement aims to limit the rise of global temperature to below the 2-degree Celsius, or 3.6-degree Fahrenheit, threshold tolerable to humanity. Meeting that target will require cutting global emissions in half in the next decade and reaching carbon neutrality, or net zero, by mid-century. That translates to a reduction of about 1.1. to 2.2 billion tons per year.

Le Quéré said the emissions drop from the pandemic could be fleeting because it resulted from “forced behavior change” as opposed to policy shifts to expand renewable energy, vehicle electrification, reforestation and other carbon-cutting investments.

“So now is the time where governments have to follow their commitments with large-scale actions, with plans, detailed plans, to move out of fossil fuels in all the sectors of the economy,” she said.

She and other researchers who conducted the analysis noted that greenhouse gas emissions are already creeping back up to pre-pandemic levels. If history is a guide, they can be expected to bounce back in 2021 as the world begins to emerge from the pandemic and economic activity rebounds.

Their analysis found that emissions cuts from the coronavirus peaked globally in the first half of April when pandemic restrictions were most stringent, especially in Europe and the United States. The biggest factor was a reduction in driving and other forms of transportation, which fell by about half during that early surge in the pandemic.

The decline was more pronounced in the United States and Europe, where the coronavirus accentuated a decrease in emissions that was already underway because of the shift from coal power. Pollution dropped by 12% in the United States and 11% in the European Union.

The reductions were smaller in other countries where coronavirus restrictions came on top of greenhouse gas emissions that are still rising. In China, emissions fell by about 1.7%, which researchers said was partly because that country’s lockdowns occurred earlier in the year and were shorter, giving its economy more time to recover.

During past economic downturns, including the 2008 global financial crisis and the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, temporary dips in greenhouse gas emissions were followed by economic recovery and a resurgence in pollution that offset any short-lived gains for the climate. Scientists said there is still an opportunity to avoid that fate if nations focus their economic stimulus and recovery plans on investments in renewable energy.

“A 7% global emissions decrease in 2020 doesn’t matter unless we sustain and accelerate those reductions after the world opens up again and the economy recovers,” said Joel Jaeger, a research associate with the World Resources Institute’s climate program who was not involved in the analysis. “Governments around the world need to agree on COVID-19 recovery packages that not only reboot the economy but transform it.”

“We know from past experience that investing big in low-carbon infrastructure can effectively stimulate the economy, create jobs and build up new sustainable industries,” Jaeger said, adding that countries must, at the same time, set strong emissions standards and policies phasing out fossil fuels.

Le Quéré said that at the moment, the stimulus plans being put in place “are really not very green, I have to say — they’re actually very dominated by investment in the sort of conventional economy. And if this continues, if there is no change, then I completely expect that the path of the emissions will come back.”

Still, there is some reason for optimism, compared with past slowdowns.

For one, greenhouse gas emissions had already been rising more slowly over the last 10 years than in the decade before, at least in part because of climate policies to shift to renewable energy.

European leaders have earmarked about 30% of their stimulus money for low-carbon projects that support emissions reduction targets. And an increasing number of nations, and states including California, have made pledges to achieve net zero emissions by mid-century or sooner. Net zero means that so few emissions are produced that they are offset by carbon-absorbing projects such as restoring forests and soils or by capturing them directly from the air.

The U.N.’s annual Emissions Gap Report said the pandemic-triggered emissions cuts could be lasting only if countries pursue a green recovery from the pandemic that prioritizes low-carbon investments. Doing so could reduce emissions by up to 25% compared with what is expected through implementation of the Paris agreement and bring the world closer to limiting global warming to 2 degrees.

The U.N. singled out the wealthy as bearing the greatest responsibility because the combined emissions of the richest 1% is more than twice that of the poorest 50%.

“This elite will need to reduce their footprint by a factor of 30 to stay in line with the Paris Agreement targets,” U.N. Environment Program Executive Director Inger Andersen wrote in the report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.