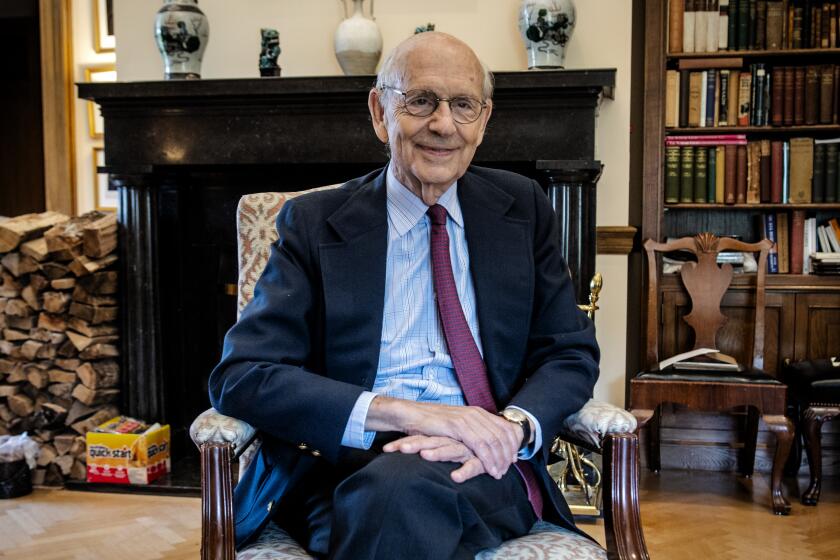

Who are Biden’s leading contenders to replace Stephen Breyer on the Supreme Court?

Justice Stephen G. Breyer’s retirement announcement gives President Biden the chance to fulfill his campaign promise to put the first Black woman on the U.S. Supreme Court.

If that happens, Biden’s pick would be the third Black justice and the sixth woman in the court’s history of more than 230 years. Biden could also heed calls from his liberal base to add professional diversity to a court without any former public defenders or civil rights lawyers.

Justice Stephen G. Breyer will retire, clearing the way for President Biden to make his first appointment to the Supreme Court.

Although the White House has been tight-lipped about its shortlist of candidates, U.S. Court of Appeals Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson and California Supreme Court Justice Leondra Kruger are the consensus front-runners among Biden’s progressive allies.

Here are possible contenders:

Ketanji Brown Jackson

Jackson, 51, is widely regarded as a leading candidate, alongside Kruger. A rising star in Washington legal circles, she is a former Breyer clerk and a federal appeals court judge who was in the middle of politically charged disputes during the Trump era. She would bring another dimension of diversity to the Supreme Court as a former public defender.

Jackson was nominated by President Obama to the federal district court in Washington, winning Senate confirmation in 2013. In her most prominent case, she ruled in 2019 that former White House Counsel Donald McGahn had to testify at a House impeachment hearing.

Jackson was nominated by Biden and confirmed by the Senate last year to the powerful D.C. Circuit to take the seat held by now-Atty. Gen. Merrick Garland. The D.C. Circuit has served as a springboard for several future justices, including the current court’s Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Associate Justices Clarence Thomas and Brett M. Kavanaugh.

Jackson, who grew up in Miami, graduated from Harvard College and Harvard Law School and clerked for two lower court judges before working for Breyer during the Supreme Court’s 1999-2000 term. During Jackson’s district court confirmation hearing, Breyer was quoted as having raved about her intellect and thoughtfulness.

In addition to working in the appeals unit of Washington, D.C.’s, federal public defender office, she served on the U.S. sentencing commission and has worked for multiple large law firms.

Leondra Kruger

Kruger, 45, offers a mix of strengths that make her one of the odds-on favorites. As a California Supreme Court justice since 2015, she has developed a reputation as a careful, incremental jurist — a trait that might disappoint some liberal advocates while potentially attracting Republican support.

She would be the youngest Supreme Court nominee since 43-year-old Thomas was selected in 1991. Her age — she is the youngest of Biden’s potential picks — means she could easily serve for three decades or more on the high court. Amy Coney Barrett, who turns 50 this week, is the youngest sitting justice.

The Southern California native has traditional bona fides, including 12 Supreme Court arguments. Kruger clerked for the late Justice John Paul Stevens and Judge David Tatel of the D.C. federal appeals court and worked in Obama’s Justice Department as a deputy assistant attorney general in the Office of Legal Counsel. Her Supreme Court cases came while she was in the solicitor general’s office, where she was named acting principal deputy solicitor general.

She would stand out as the first justice nominated in three decades with experience as a state supreme court justice. She was appointed by former California Gov. Jerry Brown and is the second Black woman to have served on the state’s Supreme Court. She is the daughter of a Jamaican immigrant mother and a Jewish father, both pediatricians.

Kruger has written a precedent-reversing decision that required a warrant for vehicle searches. Another opinion let CNN and other media organizations use a state free speech law to block lawsuits alleging workplace bias or retaliation.

In a 2018 interview, Kruger told the Los Angeles Times that her approach as a judge reflects “the fact that we operate in a system of precedent.”

Breyer’s reported plan to retire, and President Biden’s appointment of a successor, is unlikely to reduce the partisanship that has beset the court.

J. Michelle Childs

Childs, 55, may have been considered a longshot given that no federal district judge has been elevated directly to the Supreme Court since 1923. But in December she was nominated by Biden for the D.C. Circuit.

She also has an influential backer in Rep. Jim Clyburn, the South Carolina Democrat whose endorsement of Biden in the 2020 presidential primary helped rescue his flailing campaign. Clyburn told the New York Times in February Childs would be a “good addition to the Supreme Court.”

Childs would bring a different set of experiences to the Supreme Court as a non-Ivy League law graduate and a former South Carolina labor official.

Childs has been a federal judge in South Carolina since 2010, when she was appointed by Obama. Childs’ noteworthy decisions include a 2014 ruling in favor of a lesbian couple who sought to have South Carolina recognize an out-of-state marriage.

Before becoming a federal judge, Childs was a South Carolina state judge, a commissioner on the state workers’ compensation commission, and an official in the South Carolina labor department. She was also a law firm partner, focusing on labor and employment law.

Sherrilyn Ifill

Ifill, 59, would be a bold choice and send a strong statement about Biden’s prioritization of civil rights. As president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund — a position once held by the late Justice Thurgood Marshall before he was nominated — Ifill has been at the center of policy debates and pressure campaigns involving voting rights, police brutality and job discrimination.

“I have a pretty unrelenting view of justice,” she said in a 2013 interview with NYU Law Magazine. “You have to be willing to fight and lose the battle sometimes in order to win the war.”

She has also been involved in recent efforts to push Facebook Inc. and other social media platforms to do more to combat racism and voter suppression on their sites.

Biden in April selected Ifill to serve on a panel convened to study potential changes to the high court. She is a former professor who spent 20 years at the University of Maryland School of Law in Baltimore. She has written about the importance of diversity among judges in federal and state courts.

Ifill, who spent part of her career at the American Civil Liberties Union, has an undergraduate degree from Vassar College and a law degree from New York University School of Law.

Her age will almost certainly work against her given the push by both parties for younger justices who can serve longer. She would be the oldest new justice since Ruth Bader Ginsburg was appointed at age 60 in 1993.

Leslie Abrams Gardner

Gardner, 47, is another judge who would be making an unlikely leap from serving on a federal district court. A former prosecutor nominated to the bench by Obama in 2014, she became the first Black female federal judge in Georgia, winning confirmation 100-0.

She graduated from Brown University and Yale Law School and, as a private attorney, represented big corporations including Alphabet Inc.’s Google and Bank of America Corp.

Although her resume may not excite progressives seeking more professional diversity on the federal bench, Gardner has been immersed in the criminal justice system in a way few justices have.

Her husband was wrongly imprisoned for 26 years for a rape and robbery he didn’t commit before being exonerated. Jimmie and Leslie Gardner met and were married after his release. Her brother, Walter, has been incarcerated and experienced mental health and substance abuse problems.

Conservatives would likely focus on her ties to her sister, voting rights activist Stacey Abrams, who is running a second time for governor of Georgia and who was behind get-out-the-vote efforts that flipped the state blue in the presidential election of 2020.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.