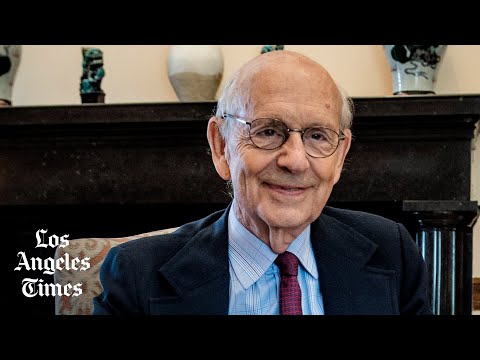

Supreme Court Justice Stephen G. Breyer to retire, giving Biden his first appointment

Justice Stephen G. Breyer, the Supreme Court’s 83-year-old liberal pragmatist, plans to retire this year, clearing the way for President Biden to make his first appointment to the high court.

WASHINGTON — Justice Stephen G. Breyer, the Supreme Court’s 83-year-old liberal pragmatist, plans to retire this year, clearing the way for President Biden to make his first appointment to the high court.

Breyer, a 1994 appointee of President Clinton, is the senior member of the three-justice liberal bloc, and his retirement is unlikely to change the court’s ideological balance.

But it should allow Democrats to replace him with a younger and possibly more assertive progressive. The confirmation process is likely to dominate Democrats’ agenda in 2022.

“President Biden’s nominee will receive a prompt hearing in the Senate Judiciary Committee, and will be considered and confirmed by the full United States Senate with all deliberate speed,” Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) said.

Breyer’s plans were first reported Wednesday by NBC News. Court and White House officials had no comment.

Biden has pledged to appoint the first Black woman to the court, and the leading candidates are Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson, 51, and California Supreme Court Justice Leondra Kruger, 45.

Jackson, who serves as a federal appeals court judge in Washington, was a Supreme Court clerk for Breyer in 1999 and 2000. In March last year, Biden nominated her to serve on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit to fill the seat vacated by Atty. Gen. Merrick Garland.

Last month, she joined a three-judge ruling of the court that rejected President Trump’s claim of executive privilege over the White House records that were sought by the House committee investigating the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol. And last week, the Supreme Court turned down Trump’s appeal of that decision with only one dissent.

Kruger served as a law clerk for the late Justice John Paul Stevens in 2003 and 2004. White House sources say Kruger was asked to serve as U.S. solicitor general for the Biden administration but declined to step down from the state high court and return to Washington. They said that might dim her chances of being nominated now to the high court.

Others who have been cited as potential nominees are J. Michelle Childs, a federal district judge in South Carolina who is a favorite of Rep. James E. Clyburn (D-S.C.), and Sherrilyn Ifill, the outgoing president of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

Asked Wednesday whether Biden might select Vice President Kamala Harris, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said the president has “every intention” of keeping Harris as his running mate in 2024.

In recent weeks, Breyer has sounded increasingly frustrated by the court’s turn to the right. When the justices heard arguments on Biden’s plan to require vaccinations or regular testing in most private companies, Breyer said it would be “unbelievable” for the court to overturn such a rule in the midst of a pandemic. But the court did just that a week later by a 6-3 vote.

The timing of his departure was probably affected by the Democrats’ narrow hold on control in the Senate. By leaving well before the 2022 midterm election, Breyer ensures Democrats will have plenty of time to replace him before the election, when Republicans hope to recapture control of the Senate.

The last time Republicans held the Senate under a Democratic president, Senate GOP leaders simply declined to act on the nominee. In 2016, then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) refused to hold hearings or a vote on Garland, President Obama’s nominee to fill the seat of Justice Antonin Scalia, who had died suddenly.

Breyer has been under heavy pressure to resign from liberals pointing to the example of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. She declined to step down when Democrats held the White House and Senate during the Obama administration, and died when President Trump and Republicans were in control, shifting the court’s ideological balance.

And even before the 2022 election, with a Senate split 50-50, some progressives worry that an unexpected shift of one seat due to death or resignation on the Democratic side could restore control to McConnell.

Breyer replaced Justice Harry Blackmun, the author of the Roe vs. Wade decision that legalized abortion. He reliably joined Ginsburg and the court’s liberals on the major issues that divided the justices. He supported abortion rights, college affirmative action and gay rights, and he dissented when the conservative majority struck down the limits on campaign spending and severely restricted the Voting Rights Act.

However, Breyer never achieved great prominence on a high court that was dominated by its conservatives and the right-leaning moderates who cast the deciding votes, including Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and Anthony M. Kennedy. Meanwhile, liberals cheered for Ginsburg and the more outspoken Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Obama’s first appointee.

Breyer is a California native, having grown up in San Francisco, and attended Stanford University as an undergraduate. But he spent most of his working life shuttling between Boston and Washington. He taught law at Harvard University and became a protege of Massachusetts Sen. Edward M. Kennedy and served for a time as one of Kennedy’s top aides in the Senate. Kennedy played a key role in winning him an appeals court seat in Boston in 1980 and a Supreme Court appointment in 1994.

Breyer brought to the high court his belief in government as a force for good, and he saw the court’s role as helping to make government work effectively. He has been the justice most likely to uphold the laws passed by Congress and regulations that were issued by federal agencies. He also focused more on the practical impact of a decision rather than on how it fit into an ideological approach to the law.

Despite his low public profile, Breyer had influence within the court because he could work with O’Connor and other moderate conservatives to shape middle-ground decisions or to limit the reach of a conservative ruling.

In 2019, for example, Breyer joined a court opinion that upheld as constitutional a 40-foot Latin cross that stood for nearly a century in a Maryland suburb as a memorial to local soldiers who died in World War I. As a condition for joining the opinion, Breyer had insisted the court not endorse erecting new religious symbols on public property, but instead accept long-standing monuments whose purpose was to honor soldiers, not to promote a religious viewpoint.

Breyer was particularly fond of O’Connor, a former state legislator, and like her, he brought a pragmatic approach to the law.

He spoke for the court in 2016 to strike down a Texas law that would have shut down most of the state’s abortion clinics because their physicians did not have admitting privileges at a local hospital and because their facilities did not have the wide hallways of an ambulatory surgical center.

Breyer’s opinion carefully explained that the evidence showed these restrictions would hurt, not help to protect, the health of the patients, some of whom would be forced to drive hundreds of miles in search of an open clinic. The approach was the kind of opinion that would appeal to swing-vote Justice Kennedy, who joined to form the majority.

Breyer’s openness to compromise did not always work. He was dejected by the 5-4 ruling in Bush vs. Gore, which halted the hand recount of punch-card ballots in Florida and preserved a narrow presidential win for then-Gov. George W. Bush.

“The court was wrong to take this case. It was wrong to grant a stay” that halted the recount, Breyer wrote in dissent. While he agreed that ballots should be recounted under a “uniform standard” for deciding whether it was a legal vote, he said it was a mistake for the court to end the recount. “We do risk a self-inflicted wound — a wound that may harm not just the court, but the nation,” he wrote on Dec. 12, 2000.

Breyer was the only justice to have worked for years in Congress, and he argued for interpreting the law in a way that carried out the intent of the legislators who wrote them. As an aide to Sen. Kennedy, he played a key role in the passage of the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978. He also helped shape the federal sentencing guidelines with the aim that prison terms should reflect the severity of the crime, not the judge who handed down the sentence.

At the court, he and Scalia were regular sparring partners, and the two carried on a long-running debate over how to decide cases that turned on the meaning of a federal law. Scalia, a conservative who was skeptical of Congress, said the court should rely strictly on the words of a statute.

Breyer, by contrast, insisted the court should be guided by the purpose of the law and interpret its provisions in line with what Congress intended. He was the justice most likely to uphold a law and the federal regulations that enforced it. Where conservatives complained of “unelected bureaucrats” and an all-powerful “administrative state,” Breyer spoke of agency officials as smart, serious-minded experts who were seeking to implement the law that came from Congress.

“The hardest problem in real cases is that the words ‘life,’ ‘liberty’ or ‘property’ do not explain themselves. Nor does the freedom of speech say specifically what counts as ‘the freedom of speech,’” he said in 2011. While Scalia thought money spent on political campaigns was fully protected as speech, Breyer disagreed and voted to uphold the limits on spending and contributions set by Congress.

Breyer voiced despair over the lingering challenge of capital punishment. Writing in dissent in the 2015 case of Glossip vs. Gross, Breyer argued that recent decades had revealed the death penalty system was broken beyond repair. He said DNA testing had shown that a significant number of defendants were wrongly convicted and some were sentenced to death for crimes they did not commit.

Breyer concluded that the death penalty had proved to be arbitrary, unreliable and unworkable, and he said the court should declare it is “cruel and unusual punishment.” Only Ginsburg signed on to his dissent.

Breyer’s usual tone was hopeful and optimistic. In a 2010 book called “Making Our Democracy Work,” Breyer said informed citizens, elected officials and judges must constantly work together with the aim of improving government. Yet from his Supreme Court chamber, he watched each year as Congress grew ever more divided, with members unwilling to work with or even speak with those on the other side of the aisle.

Over the years, several justices — but not Breyer — quit attending the annual State of the Union speech in which the president addresses the House and Senate in a joint session. His colleagues complained the speeches had turned into partisan pep rallies. Breyer believed that attending was a symbol of the different branches of government joining to work together in the year ahead.

Though he was often on the losing side when the justices were closely split, Breyer disputed the view that the outcomes turned on the political views of the justices. Asked in a 2020 interview about what most people get wrong about the court, he replied: “I think the most common perception, which is wrong, in my opinion, is they think that we’re just junior-league politicians and they think that all these cases are decided on political grounds. We won’t always get it right, but we’re trying to do our best to figure out how law applies in this situation. And that’s sometimes pretty tough. And the decisions people think are so obvious, they’re not so obvious.”

Stephen Gerald Breyer was born Aug. 15, 1938, in San Francisco, where his father, Irving, served as the legal counsel for the San Francisco Board of Education. He graduated from Lowell High School in 1955 and earned an undergraduate degree from Stanford. He was awarded a Marshall scholarship to study at Oxford and then returned to the U.S., where he earned a Harvard law degree.

He first came to Washington in 1964 to be a Supreme Court clerk for Justice Arthur Goldberg and then joined the Justice Department in the antitrust division. In 1967, he married Joanna Freda Hare, a child psychologist who was a member of the British aristocracy. They had three children: Chloe, Nell and Michael. Breyer’s younger brother Charles was a federal district judge in San Francisco.

Breyer missed his first shot at the Supreme Court. In 1993, shortly after Clinton moved into the White House, Justice Byron White announced his plan to retire. Democrats were eager to fill their first Supreme Court seat in 26 years. Clinton set out to select a prominent Democrat with experience in the political world, but New York Gov. Mario Cuomo and Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell, a former federal judge, declined the offer. He had initially declined to consider Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg because she had given speeches in which she criticized the Roe vs. Wade ruling.

Breyer had the support of top White House lawyers as well as Sen. Kennedy, and Clinton invited him to the White House. But Breyer had been badly injured in a bicycle accident and suffered broken ribs and punctured lung. Nonetheless, he traveled to Washington for what turned out to be a difficult and painful interview. Clinton and Breyer had differing views on antitrust law, and the president did not come away impressed. After more weeks of delay, Clinton invited Ginsburg for an interview and immediately decided to nominate her to the court.

A year later, however, Justice Harry Blackmun retired. And while Clinton again reached out to several prominent figures, he relented and nominated Breyer, who appeared to face no real challenge in the Senate. He won confirmation on an 87-9 vote.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.