Editorial: Justice Breyer’s retirement preserves Supreme Court status quo, for good and bad

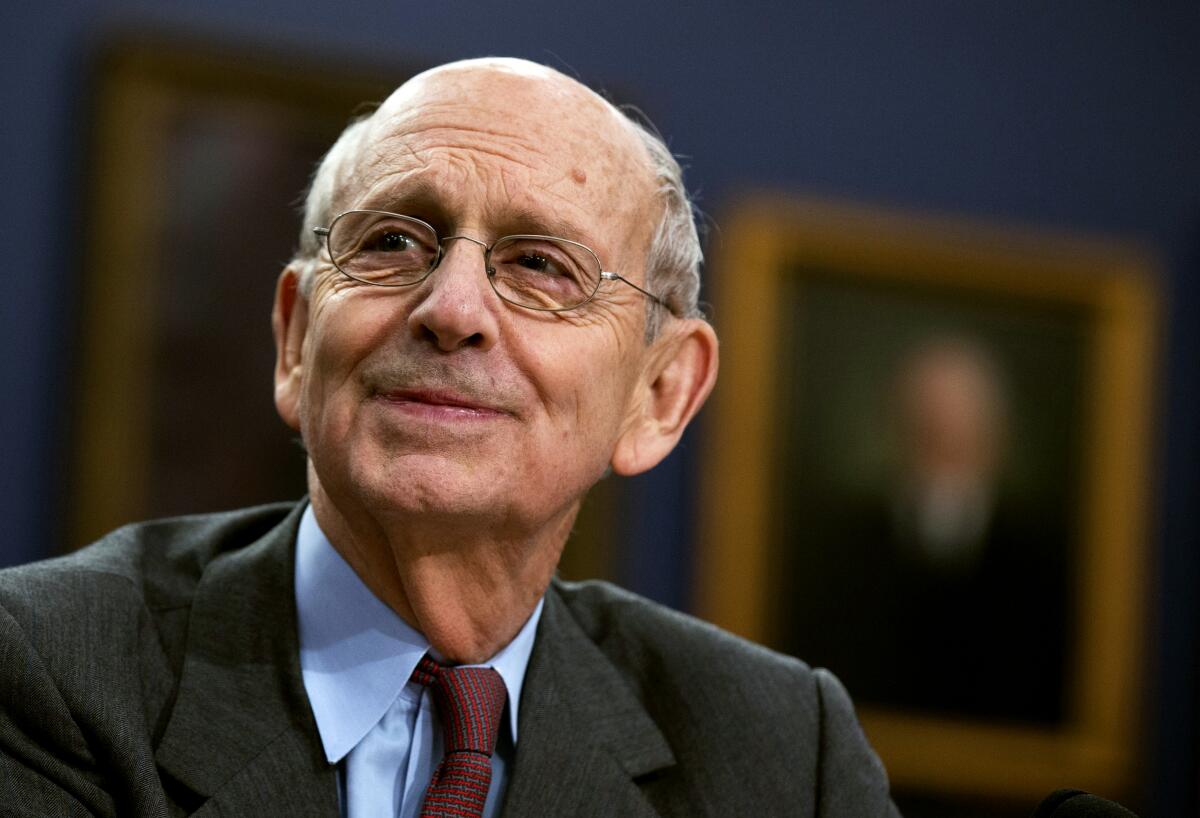

Justice Stephen G. Breyer has made many rulings during a long and distinguished career, but his most consequential may turn out to be the one reported Tuesday: He will retire from the U.S. Supreme Court at the end of its current term in June, allowing President Biden to nominate his replacement, and a Senate barely controlled by Democrats to confirm the appointment.

The issue of timing has hounded Breyer, a liberal justice and a native Californian, for more than year. At 83, he’s now the oldest justice by a decade and has served on the court for more than 27 years. The question many observers asked was whether he would step down before the looming midterm election, when Republicans could take control of the Senate.

Political partisanship ought to make little difference to the court’s composition, but the sorry fact is that it does. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) last year said that if Republicans took back the Senate, it would be “highly unlikely” that any Biden nominee would be confirmed.

Fixed terms would lower the political temperature of Supreme Court appointments

That approach continues the increasing politicization of the court, which has ramped up to extreme levels during McConnell’s tenure as Senate majority leader, first in 2016 when he refused to even consider President Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland on the specious argument that it was a presidential election year and any appointment should hold until there was a new president. Yet when Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died in September 2020, with Donald Trump in the White House and just weeks before a presidential election, McConnell moved quickly to confirm the nomination of Amy Coney Barrett, Trump’s third Supreme Court appointment.

Regard for the court as a nonpartisan institution that rules according to the law and the Constitution, and not partisan loyalties, has suffered. Calls for Breyer to retire while Democrats control the White House and Congress are unseemly, as they were for Ginsburg, but understandable.

This problem could be resolved in part by limiting the justices’ terms to 18 years. That would permit a predictable schedule of presidential appointments.

In the meantime, Republicans could fix some of the damage caused to the court and the confirmation process by supporting any qualified Biden nominee.

And Biden, for his part, should swiftly nominate Breyer’s successor, allowing the confirmation process to move forward well in advance of the midterm election.

Breyer’s retirement won’t reverse either the destructive partisanship that has undermined the court or the court’s increasingly conservative political orientation. He is a liberal, although by no means a leftist progressive, and Biden will likely choose someone with a similar outlook to replace him.

But the timing of his retirement means that, at least for now, the partisanship is unlikely to get much worse.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.