California’s immigrant crackdown propelled Latinos to Washington. After Trump, could it happen again?

WASHINGTON — Businessman Lou Correa abandoned plans to join the Republican Party. Raul Ruiz, a UCLA student on the cusp of medical school, discovered a passion for public policy. Juan Vargas, who had weighed the seminary, finally found his calling — getting more Latinos to vote and run for office.

The spark behind the seismic shift in each man’s life: California’s infamous Proposition 187, the initiative voters overwhelmingly approved in 1994 to deny services to those residing in the country illegally.

Ruiz, Correa and Vargas all would become members of Congress.

So would Jimmy Gomez, Pete Aguilar, Tony Cardenas, Norma Torres and Alex Padilla.

Long before a president called Mexicans crossing the southern border rapists, Proposition 187 galvanized a generation of California Latinos into joining civic life and Democratic politics in numbers never before seen, marginalizing the Republican Party for decades to come. It’s a familiar political tale.

Perhaps less well known is how many of those activists ended up as Democrats in Congress, and how memories of the fight over that divisive initiative continue to guide their actions to this day.

“Did it inspire me to get more engaged?” Rep. Ruiz, of Palm Desert, asked. “Hell yeah.”

Looking back, Ruiz and other lawmakers say the unsuccessful fight to stop Proposition 187 changed their trajectories — and they wonder whether former President Trump’s nativist rhetoric and immigration policies could spark a national political awakening among a new generation of Americans.

To many Latinos, Proposition 187 carried an implicit threat that they didn’t belong.

“I felt like they were kind of saying, OK, even if you were born here, you’re still not really an American, no matter what, even if your birth certificate says you’re a U.S. citizen,” Rep. Gomez, of Los Angeles, said.

In 1993, California faced its worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. Republican Gov. Pete Wilson faced a tough reelection campaign in an increasingly racially and ethnically diverse state that was already leaning blue. The solution Republicans arrived on was Proposition 187, which denied even children public healthcare and education, and which ordered state officials to report to the federal government those suspected of not having legal status.

A podcast from the Los Angeles Times and Futuro Studios looks at how Prop. 187 helped turn California into the progressive beacon it is today.

Rep. Aguilar, of Redlands, recalled how Wilson and the GOP pushed the initiative, demonizing immigrants as they did so. “Clearly,” he said, “this is what the Republican Party stood for.”

The proposition

When Proposition 187 made the ballot in 1994, activists and students like Ruiz scrambled to mobilize protests. More than 70,000 people marched on Los Angeles City Hall, the largest protest L.A. had seen since the Vietnam War. Tens of thousands of middle and high school students staged mass walkouts in defiance of school administrators and public officials who demanded they stay in class.

Ruiz was already involved in community organizing around health and Chicano issues but hadn’t planned on a career in politics. He had promised people in the Coachella trailer park he grew up in that if they would cobble together tuition for him, he would return one day as a doctor.

Proposition 187 showed him policy was integral to public health. Later, when he went to Harvard to complete his medical studies, he tacked on dual masters in public policy and public health.

The initiative also was a turning point for Correa. The Orange County businessman was volunteering for Democrat Loretta Sanchez’s Anaheim City Council campaign but quietly weighing whether to become a Republican.

He says he had a voter registration card filled out, ready to drop off. But he couldn’t, not after Republicans blamed immigration for the state’s woes. He joined the fight against Proposition 187.

“I was actively out there volunteering to say this is not American, this is not right,” Rep. Correa said. “All of us had essentially grown up with part of our family undocumented or our friends and our neighbors undocumented.”

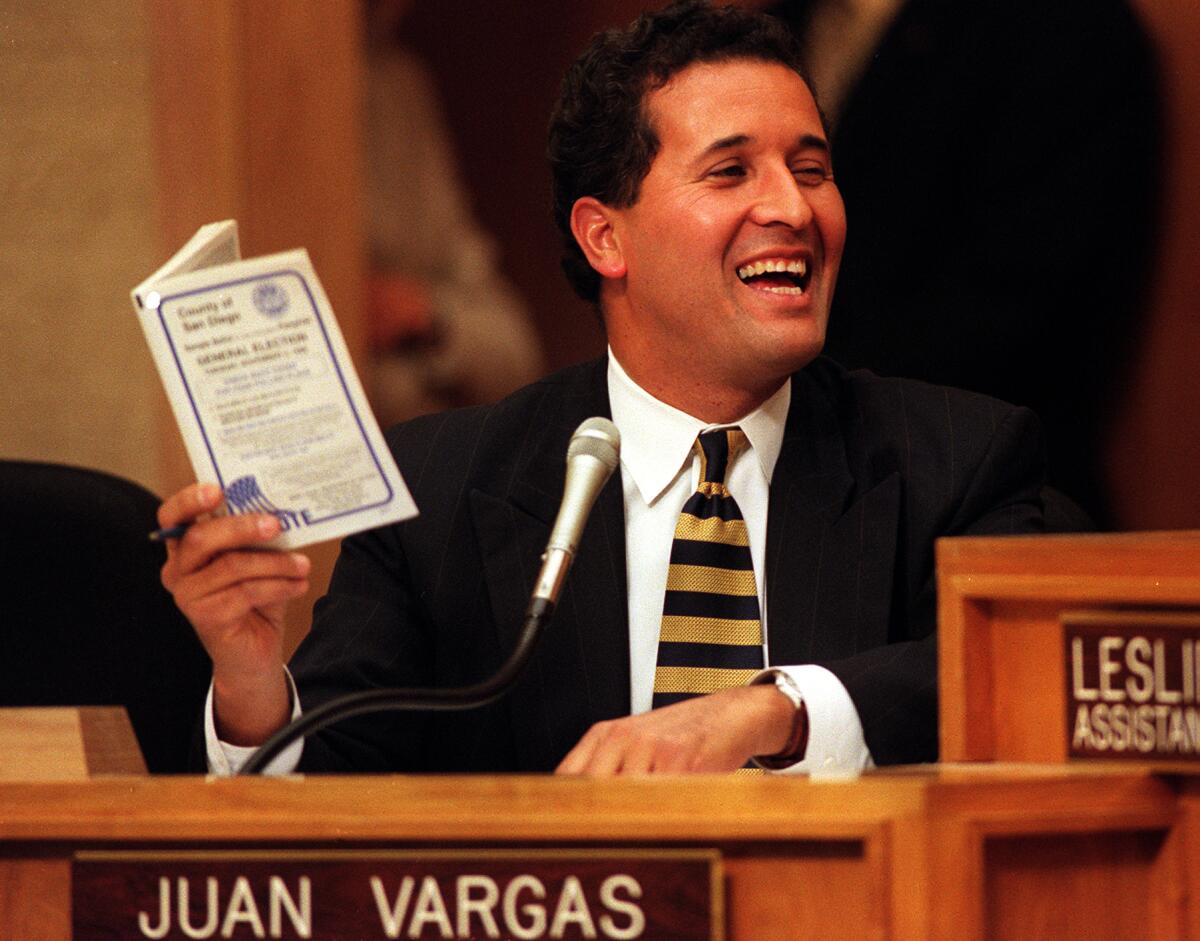

Vargas, of San Diego, had given up his dream of becoming a Catholic priest and was searching for another calling when he learned about Proposition 187. Though serving his first term on the San Diego City Council, he was debating whether he should return to a lucrative career as a lawyer.

Then voters passed the initiative 59% to 41% and propelled Wilson to another term.

“I couldn’t get up the next morning,” Rep. Vargas said. “I thought it was a disaster for California — turned out of course, to be the best thing. It really did wake up a sleeping giant.”

State and federal lawsuits kept Proposition 187 from ever going fully into effect. A judge ruled it unconstitutional in 1997; Wilson’s successor, Gray Davis, dropped the state’s appeal in 1999.

A look back at the events surrounding the 1994 proposition.

Still, appalled Latinos registered to vote, volunteered on campaigns and ran for local, state and federal office in unprecedented numbers.

Vargas estimates that he helped 10,000 people become voters. After seven years on the City Council and a dozen years in Sacramento, Vargas went to Congress in 2013, where the soft-spoken San Diegan became a well-known advocate for providing immigrants access to public and financial services.

“Proposition 187 really gave me a problem to work on, a big problem that was very meaningful,” Vargas said.

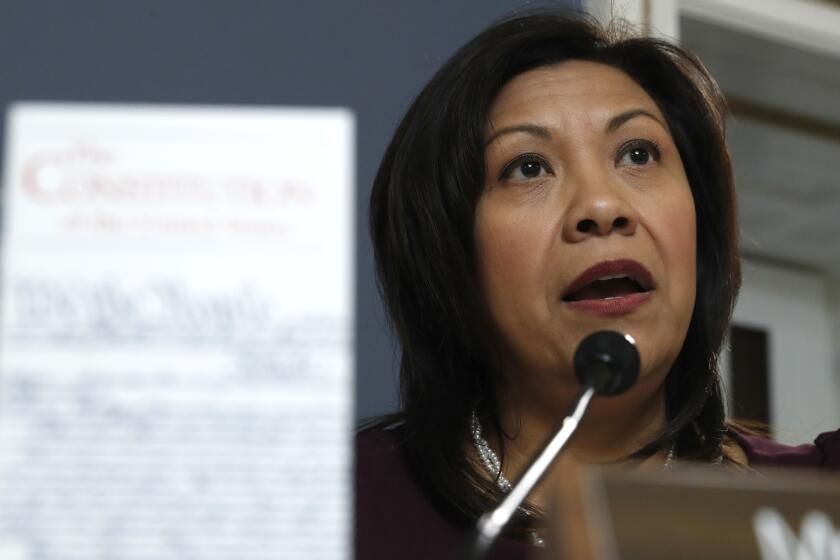

Many Latinos in California, like Torres, also became U.S. citizens after decades as legal permanent residents. Union organizing led Torres to the Pomona City Council, the statehouse and then Congress.

Correa had planned on an investment career but pivoted to politics because he saw history repeating itself in Proposition 187’s effect on the U.S.-born children of immigrants in the country illegally, reminding him of how his American citizen father went to live in Mexico during the 1930s economic downturn because his own parents, who weren’t citizens, were deported.

Correa lost his first bid for state Assembly in 1996 by 93 votes but easily beat the Republican incumbent two years later. Decades in state and local politics led him to Congress in 2016, to replace Sanchez.

Meanwhile when Cardenas, of Los Angeles, entered his first race for the Assembly, he asked Padilla, who had abandoned an engineering career to fight Proposition 187, to manage that 1996 campaign. Now, they are colleagues again on Capitol Hill. Padilla is the first Latino to represent California in the Senate.

California’s Norma Torres fled Guatemala at 5. Now the only Congress member from Central America says the immigration debate is ‘very, very personal.’

Rep. Cardenas became chairman of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus’ fundraising arm and helped double the number of Latinos in Congress. Within California’s 53-member House delegation, the number quadrupled to 16 from four since 1994.

The president and the future

Several lawmakers told The Times they had immediate flashbacks to Proposition 187 when Trump began his campaign for president with a jaw-dropping statement about people crossing the border from Mexico bringing drugs and crime.

The anger and dismay Proposition 187 had triggered came back, the Latino lawmakers said, as the Trump administration forcibly separated thousands of children and their parents at the U.S. border, and proposed disqualifying people from obtaining green cards if they had used public health, food and housing assistance, or might use such public assistance in the future.

That so many Americans supported Trump’s actions and words was a jolt that brought many anti-Trump voters to the polls in 2020, Cardenas said.

“A lot of us from California said that what Pete Wilson was to California, Donald Trump’s going to be that for the country. And I think that we’re seeing signs of that: people who got shaken up and realized it was the president of the United States who called you an ‘other’ and that’s a nice way of putting it,” Cardenas said.

Latino leaders in California working to mend the GOP’s relationship with their community were filled with dread, not joy, as Donald Trump clinched their party’s nomination for the presidency.

Early evidence from political and advocacy groups suggests Latino voters got more involved in national politics since Trump took office, with more Latino candidates running for office in 2018 and 2020. Naturalization applications have rebounded since President Biden rescinded many of Trump’s immigration policies.

Still, Gomez said, different factors are in action now, and a repeat of 187’s activism could play out differently at a national level. The country’s Latino electorate is far more diverse than the largely Mexican American population of California that poured into the streets to protest Proposition 187.

“We lack a common cohesiveness because we have different identities and different histories,” Gomez said.

Florida and New York are more likely to be home to those whose families originated in Cuba, Puerto Rico or the Dominican Republic. Many states have seen more recent Central American immigrants, while some parts of the Southwest have Latino populations dating to when the states were still part of Mexico.

Although Latinos were a crucial part of Democrats’ ability to win the White House and the Senate in 2020, they also turned out for Trump at greater than expected numbers, even in California and especially in Texas and Florida.

The Pew Research Center’s just released analysis of validated voters shows that Trump won 38% of Latino voters in 2020, up from 28% in 2016.

Trump made the 2016 election about immigration, said Stephanie Valencia, president of Equis Research, a Latino-focused Democratic polling and research firm. But the COVID-19 pandemic and the nationwide shutdowns made the presidential election about the economy, an issue that Latino voters, like most Americans, routinely list as their most pressing concern.

Latino lawmakers said it could be years before it is clear whether Trump’s rhetoric and policies will stir younger Latinos the way Proposition 187 mobilized them, but some already point to signs of a new kind of activism.

“In California, it was precise, it was the young Hispanics that walked out of high schools ... and organized the protests and the marches against Proposition 187,” said Ruiz, who now heads the Congressional Hispanic Caucus. “With Trump, it was a broad coalition, a multiethnic group that bonded together. Our young population is now more diverse than ever, and their memories are long.”

In California, such memories ensured that Latino voters would not forget Proposition 187 or that Wilson had championed it.

Gomez, who came to politics through a community-organizing class after Proposition 187, said that in 2006 labor unions still used Wilson “as the boogeyman to mobilize the Latino vote.” He expects the same for Trump.

When Ruiz first captured his congressional seat in 2012, ousting Republican incumbent Mary Bono Mack, he ran campaign ads with a photo of her posing with Wilson. The former governor had been out of office for 13 years but, as Ruiz said, memories are long.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.