Something was about to go down and no one wanted to make the first move.

My best friend Art and I stood in the quad at our usual lunch spot: near the fountain, under the big trees. Jocks and nerds, stoners and band geeks, cholos and artsy types milled about.

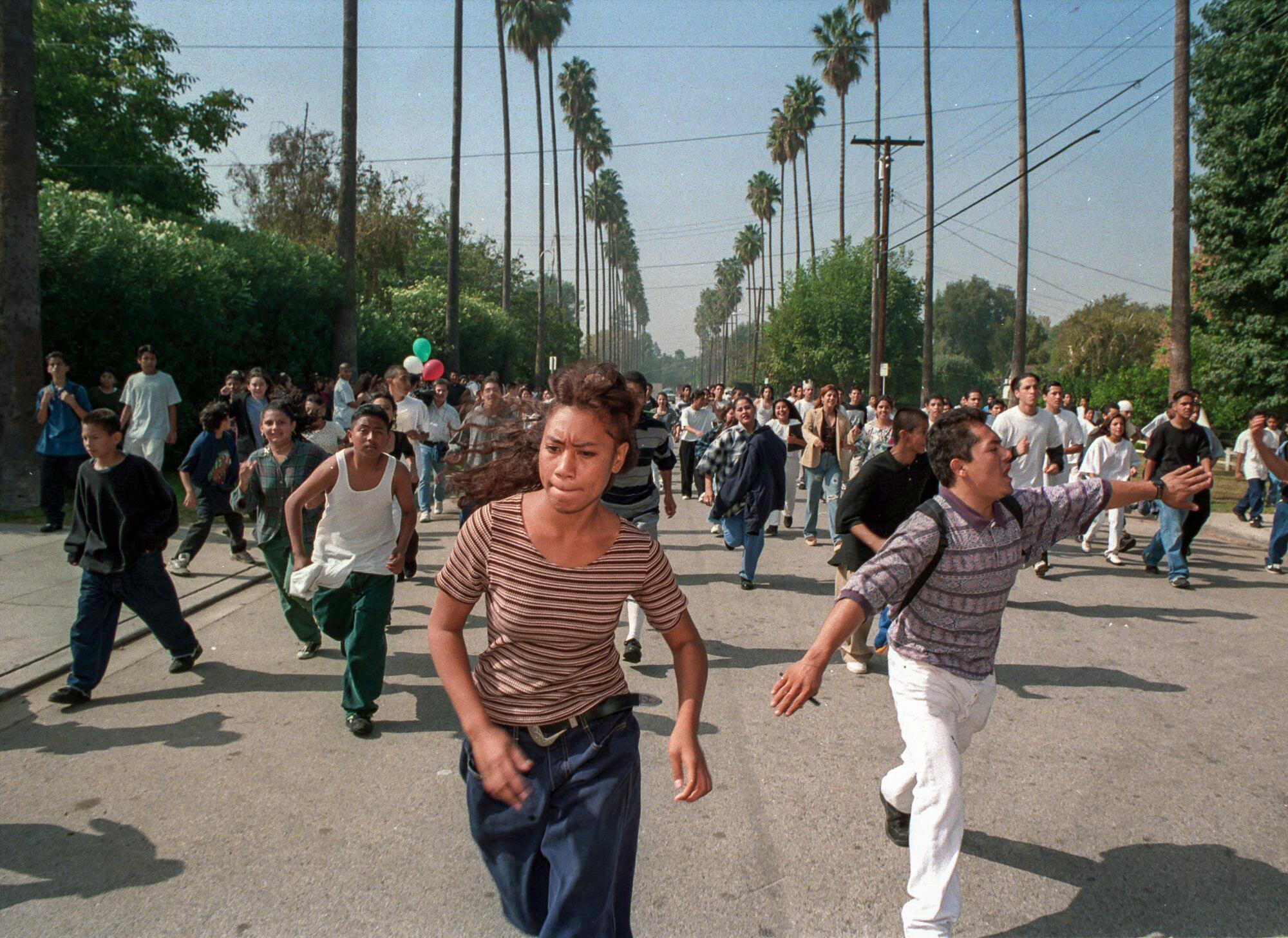

Finally, one kid walked to the chain-link fence that separated Anaheim High School from the street. He threw over his backpack and climbed. Then another. More. Dozens. So many the fence collapsed from the weight. A stream of students swelled into a flood that converged with a political tsunami.

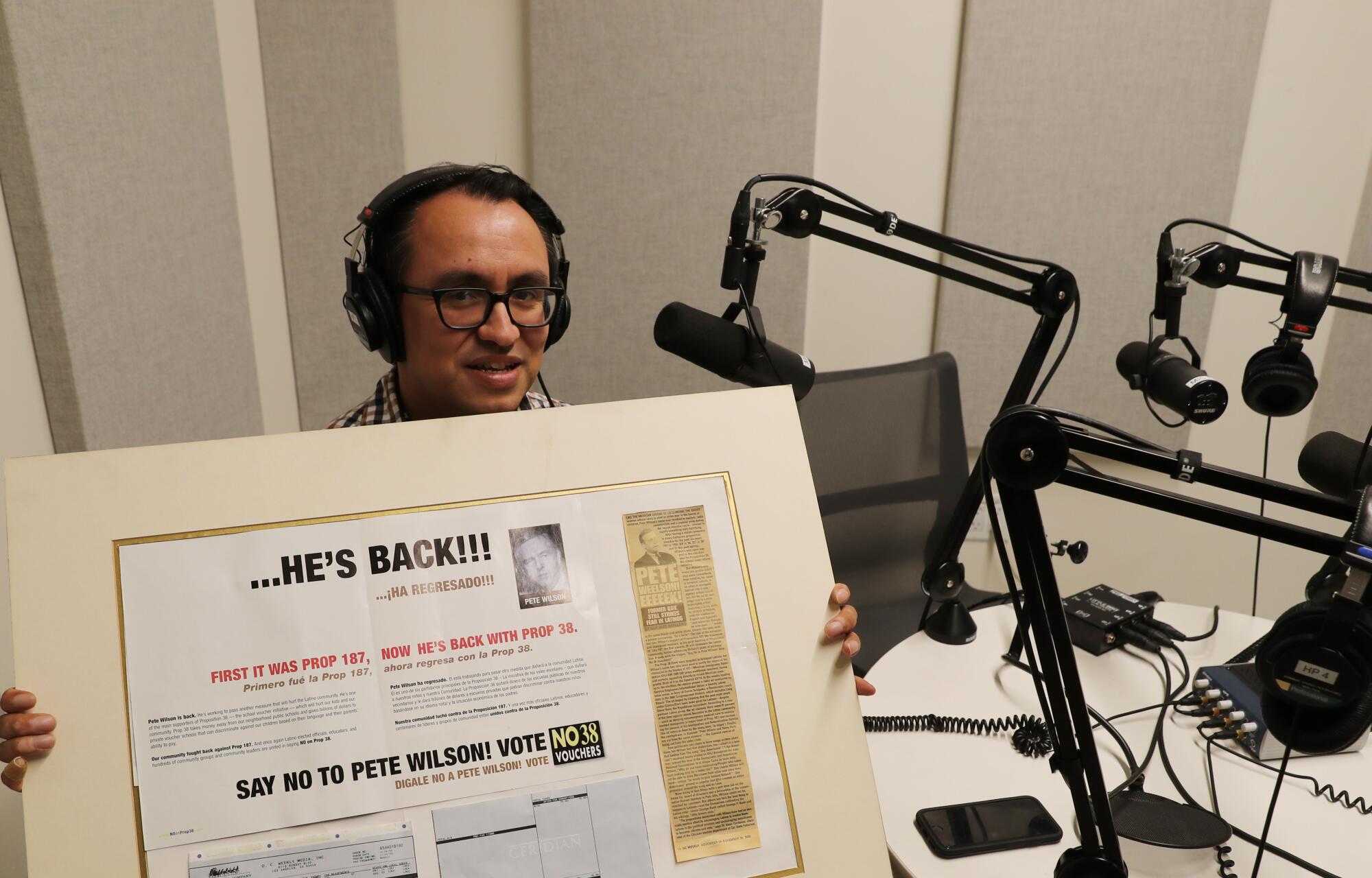

Host Gustavo Arellano looks at how Prop. 187 helped turn California into the progressive beacon it is today.

On Nov. 2, 1994, over 10,000 teenagers across California walked out to protest Proposition 187. The initiative sought to punish undocumented immigrants by denying them certain services, including access to public healthcare and education.

Proposition 187 split the psyche of the state like few things before or since.

Californians, confronted with a more diverse state and battered by the state’s worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, came to believe the problem was immigrants in the country illegally and their children.

Gov. Pete Wilson, facing an uphill reelection campaign, led the charge, releasing campaign ads that showed grainy footage of people swarming across the San Ysidro border crossing as an ominous voice intoned: “They keep coming.”

Many Latinos, legal or not, saw the proposition as an existential threat. Wilson’s “they” looked an awful lot like them.

The student marches were the culmination of a month of anti-Proposition 187 teach-ins, debates, letter-writing campaigns and some of the largest protests California had seen since the Vietnam War.

It didn’t work. The initiative easily won. Pundits declared Wilson a genius and predicted his victory, and the ballot measure he tied his fortunes to signified a major political realignment in California.

For a time, it seemed like it.

The true battle of Proposition 187, however, was just beginning.

By the time it was over, the state that gave America conservative icons Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan was on the road to becoming a progressive powerhouse. Within 20 years, California was officially a “sanctuary” state, one where undocumented immigrants could get everything from free healthcare to driver’s licenses to even serve on state commissions.

And many of the young Proposition 187 protesters were now leaders running the state.

“What 187 did is spawn a new generation of politicians,” said Kevin de León, the former president pro tem of the California Senate who was in his early 20s when he helped to organize a rally outside Los Angeles City Hall that drew more than 70,000 people. “There’s no question about it. There’s no ambiguity. There’s no vagueness. There’s no room for misinterpretation.”

But Proposition 187 did something else: It gave Republican politicians a template with which to win elections and nativist hearts across the United States.

The hard feelings against immigrants — most notably those in the country illegally, but if we’re honest, not always — was tapped all the way to the White House by one Donald Trump.

Trump the candidate said of Mexican immigrants: “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re not sending you.... They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.” As president, he speaks of invasions and criminals and “illegals” and “big, beautiful walls.” And yes, that feels like deja vu. But the vocal and angry rejection of Trump’s views across America also feel like an another byproduct of the Proposition 187 battle.

So many have found a voice.

“When I answer the question, ‘Why are you so passionate about civil rights or combating inequality,’ I tell them ‘Prop. 187,’” says Adrienna Wong, staff attorney at the ACLU of Southern California. She attended elementary school in the San Gabriel Valley during the campaign, and learned about it when “kids that I’ve been in the same class with for years started saying things like, ‘You and your family should go back to where you came from. You’re taking our jobs.’”

A look back at the events surrounding the 1994 proposition.

Back in the fall of 1994, my first brush with immigration politics came when I was walking home from Anaheim High School and a truckful of white teenage boys yelled at me “187! 187!”

I had no idea what they meant, until I got home and turned on the news. Those white boys who yelled at me were all the explanation I needed about the proposition.

I wanted to fight back, but had no idea how. Then, word soon spread around campus about an upcoming anti-Proposition 187 walkout.

No one imagined any of what would become the initiative’s legacy when my classmates left campus en masse one November day.

All we knew was that many adults had spent all of 1994 accusing our parents of destroying California.

And we weren’t going to stay quiet anymore. And so many of us climbed over that fence. But not me. Not that day.

I hung back. My friends ended up on the local news, while I was one of maybe six students in my fifth-period history class.

We didn’t say a word about what had just happened. We were ashamed for not being out there.

**

Proposition 187 started almost as a fluke.

Barbara and Bob Kiley, a husband-and-wife political consultant team from Yorba Linda, had a gadfly friend named Ron Prince who wanted to put a proposition on the California ballot. They said they had Prince stand outside a supermarket with a notepad to try to get signatures for his various causes.

None hit until one day in the fall of 1993, when Prince placed on top of his notepad the following prompt: “Do you believe illegal immigration is a problem in California?”

“He comes back with pages of signatures,” said Barbara, who was also Yorba Linda’s mayor at the time. Impressed, she said she told Prince: “You know, Ron? I think you got something here.”

(I could not reach Prince via phone, email or intermediaries.)

The Kileys, though longtime conservative activists, never felt illegal immigration was a problem. But they put together a dream team of anti-immigration hardliners — former immigration officials, politicians, attorneys, activists — to figure out what everyone could accomplish together.

The group christened their campaign Save Our State — “SOS,” for short. They came up with the name after four rounds of margaritas during a strategy session at an El Torito in Orange, Barbara said.

Proposition 187 officially qualified for the election in June 1994 and was coincidentally assigned the same number that California’s penal code designates for murder.

It arrived at the perfect time. Things had gotten tough in the Golden State, and Democratic and Republican voters and politicians alike believed illegal immigration threatened the California dream.

Early polling on Proposition 187 found a majority of Latino voters actually supported the measure.

Major Democrats such as Dianne Feinstein stayed largely silent. Chicano activists criticized mainstream groups such as Taxpayers Against 187 and Democratic politicians for being too meek.

They never expected something as blatantly xenophobic as Proposition 187 to ever qualify in California.

“Save our state from what? From me?” said Gerardo Correa, now an assistant principal at Saddleback High School. Born in Mexico and smuggled into the United States at age 2, Correa was about to become a sophomore at La Puente High School when he learned about Proposition 187 during a Chicano student conference in Sacramento.

He remembered thinking: “I’m a threat to you? Like, I’m a law-abiding citizen. I’m gonna try to go to school. I’m trying to better myself. Like, how am I the threat?”

Eventually, Correa and his friends joined hundreds of high school and college students at Fresno State University during the summer for a weekend strategy session. There, the seeds of the Nov. 2 walkouts were planted.

“People were working on, like, ‘OK, you’re going to get in contact with Roosevelt High. You’re going to get in contact with kids in Orange County,’” said Ulises Sanchez, a political consultant who was 14 at the time. “‘Then, we’re going to go to class. Then, when it’s time, you walk out.’”

**

I grew up in Anaheim, less than half an hour from the Kileys’ well-kept Yorba Linda home.

My father originally came to this country in the trunk of a Chevy in 1968, and sneaked across the border many times afterward. (He’s now a U.S. citizen.)

Every white family in my neighborhood except for one moved within five years of my family’s arrival. My world was one where no one distinguished between “legal” and “illegal” immigrants, and deportation was just a way of life that $1,000 and a smart coyote could solve.

And yet I agonized about whether to join the Proposition 187 opposition.

My friends and I debated whether we should walk out. We asked what ditching school would accomplish. If we walked out, how many other students would we actually be joining? Then there were the surprises, like finding out that a classmate whose parents were refugees from El Salvador supported Proposition 187 and railed against “illegals.”

Still, when the big day came, my Salvadoran friend walked out.

And I didn’t.

Proposition 187 disgusted me — but not enough, in that moment of my life, to spur me to action.

I was too scared, honestly: of police, of la migra, of detention, of anything remotely radical.

And I didn’t think we’d achieve anything by ditching class.

But my peers did.

They drew national attention, especially after many waved Mexican flags. That was red meat for critics, who seemed awfully forgiving when other groups, such as Irish and Italian Americans, waved the flags of their forebears.

To these critics, waving the Mexican flag was little less than sedition.

Democratic bosses were horrified by the Mexican flags. I winced when I saw the tricolor in newspapers and on television — though I got why people did it, I felt the gesture wasn’t going to do any favors with on-the-fence voters.

Proposition 187’s architects, meanwhile, were thrilled.

“That was just a godsend for them [to] start doing that,” Bob Kiley said. “It was a gift. ‘Thank you very much. I don’t have to do any more. It’s over.’”

He was right, at first: Voters overwhelmingly supported Proposition 187, by 59%-41% — a bigger margin of victory than even Wilson got.

But the day after it passed, eight federal and state lawsuits held up the full implementation of the proposition. A judge ruled it unconstitutional in 1997; Wilson’s successor, Gray Davis, dropped the state’s appeal in 1999.

That’s when Proposition 187 died.

In body, if maybe not in spirit.

**

It’s a question I ask almost everyone I’ve interviewed about all of this in recent months: Did Proposition 187, in some odd way, actually win?

Trump stirred millions of Americans to elect him with words that actually make Wilson’s rhetoric against illegal immigration a generation ago seem almost tame by comparison.

The answers I got were mixed.

“I don’t have to like Trump, but I like what he does” against illegal immigration, said Barbara Kiley. “We needed a junkyard dog. We needed somebody who could repo your car and not even think about it the next day.”

“You know, Nixon used to talk about the silent majority,” said Peter Nuñez, a former U.S. attorney who helped hammer out the language of Proposition 187. Today, he’s the chairman of the board of directors for the Center for Immigration Studies, a controversial group that favors strong restrictions both against illegal and legal immigration. “I think that silent majority still exists, and that’s why Trump got elected. And immigration was a big part of that.”

For the people forged in the fight against Proposition 187, there’s exasperation. This again? Yet it’s because of their memories that they remain confident that Trump too shall pass.

Correa said he thinks Trump will build some momentum by criticizing immigrants. But he believes that, in the end, the national Republican Party will find as Pyrrhic a victory in following him as the California GOP found with Proposition 187.

“[It] motivated us to do more, to take action,” he said. “To go to college to become professionals.”

Every year, Correa visits the state Capitol in Sacramento with the latest class of the Chicano Latino Youth Leadership Project, or CLYLP. It’s the group he belonged to when he first heard about Proposition 187. Correa’s now president of the nonprofit.

“When I went to the conference in ’94, I sat in the Assembly for it. And I remember seeing two, maybe three Spanish surnames. I remember Art Torres, maybe [Richard] Polanco and [Richard] Alarcon … maybe.”

“But now,” he continued, “I went back, and I counted 36 names. So you talk about impact. You talk about a change. I mean, I’m looking at this board of legislators, I’m like, ‘There it is. It’s right there.’”

At his office at Saddleback High, Correa keeps a letter that Wilson sent to CLYLP in 1994 offering his “best wishes” for all attendees. Sacramento, he promised, “will provide you with an opportunity to learn about the political process in California firsthand.”

“Little did he know,” Correa said with a laugh.

**

Save for the downed fence, it was as if nothing had happened at Anaheim High the day after the early November Proposition 187 walkout.

For nearly all of my classmates who participated, it would be their first and last demonstration. They went on to normal, working-class lives — teachers, construction workers, city jobs, the military. Indeed, when I reached out to some on social media and asked whether I could quote them about their memories, they declined.

They had done their job. Living fruitful lives was a direct repudiation against what Proposition 187 represented.

Life moved on for me after the walkouts too. Nothing changed for my family or even my undocumented friends, so I figured the battle was over.

I paid no attention to Proposition 187’s limbo in the courts, or the brewing Latino political revolution. If anything, I wanted to stay away from anything Mexican or political. I dreamed of moving to south Orange County and living in a gated community, far away from any problems.

“We [Latinos] became voters,” Gloria Molina said. As an L.A. County supervisor, she received hundreds of racist phone calls and hate mail for publicly opposing Proposition 187. “Everybody woke up and said, ‘It passed. It shouldn’t have passed,’ and then did something about it.”

“Pete Wilson transformed us all,” said Lisa Garcia Bedolla, vice provost for graduate studies at UC Berkeley. The Downey native has written multiple scholarly articles, studies and books about the proposition’s impact on Latinos who grew up in the era. “I don’t know if he knows that, and I don’t know if that’s what he wants to be his legacy, but that’s how it is.”

But in 1999, when Anaheim Union High School District trustees were going to vote on whether they should sue Mexico for $50 million for educating the children of immigrants in the country illegally, I was the first person to offer comments.

Hundreds of people had crammed into the district’s board room, including some of Proposition 187’s authors.

All I saw, on television and in front of me, was hate against people like me.

It was Proposition 187 all over again.

But now, I was ready to step up to that fence.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.