Bernie Sanders says he won the ideological battle for the Democratic Party. Is he right?

After two weeks of punishing losses, Bernie Sanders, stone-faced and somber, declared a triumph of sorts.

“Poll after poll, including exit polls, show that a strong majority of the American people support our progressive agenda,” the Vermont senator said. It was proof, he said, that “our campaign has won the ideological debate.”

Declaring moral victory is a familiar fallback for candidates whose chances for actual victory have greatly diminished.

Sanders, however, has had uncommon influence in Democratic policy debates over the course of his two presidential campaigns by redefining what could be considered politically realistic.

With his path to the nomination increasingly tenuous, Sanders has signaled he wants the Democratic debate on Sunday, his first one-on-one face-off with former Vice President Joe Biden, to be a battle of ideas. He hopes to recapture the momentum by winning on the merits of an agenda that includes his calls for free college tuition and raising the minimum wage.

Those have been embraced, to varying degrees, by state and local governments, corporations and rival politicians. His signature policy, Medicare for All, became the healthcare yardstick against which all his opponents were measured. Newly prominent activists on climate change cite his presidential bids as inspiration.

“He’s brought a bunch of ideas that have been marginal — at least within the American mainstream — fully into the conversation, and at least a majority of Democrats in exit polls say they support them,” said George Goehl, director of People’s Action, a progressive organizing group. “That’s a pretty damn big deal.”

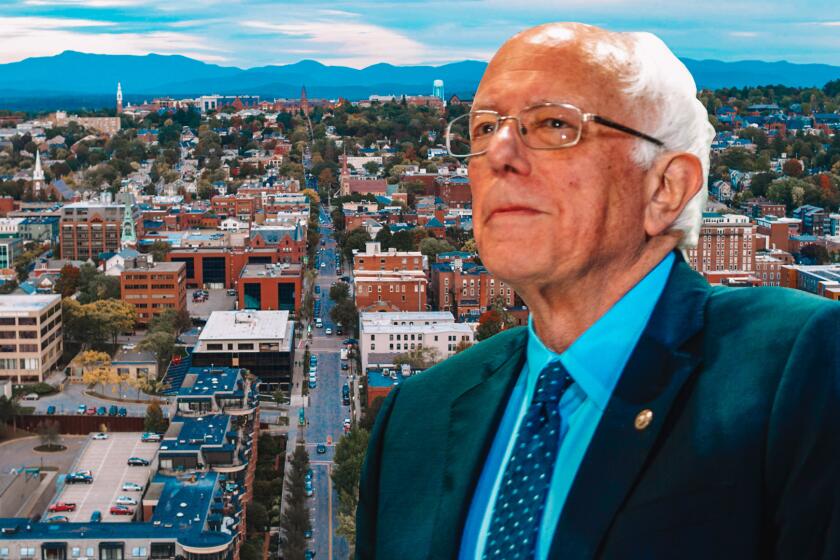

Burlington shaped Sanders as Sanders shaped Burlington, so much so that it’s hard to consider one without the other.

His challenge, which Sanders acknowledged last week, is that electability, not progressive purity, appears to be the prime motivator for Democratic voters desperate to beat President Trump in November.

“We’re at a point where people are like, we can fight those ideological battles once we’ve made sure the republic survives,” said Addisu Demissie, who ran New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker’s presidential campaign.

Will Marshall, president of the Progressive Policy Institute, a centrist Democratic think tank, pointed to one glaring reason to be skeptical of Sanders’ assertion of victory: He’s losing.

Sanders has been “rejected in fairly emphatic fashion thus far in the nomination race,” Marshall said. “Then you have to ask whether what Bernie Sanders is pushing has really appealed to the majority of voters.”

When Sanders asserted he was winning on ideology, Mark Longabaugh, a top advisor for Sanders’ 2016 run, countered with a slight tweak: Sanders was winning on the issues.

The difference was subtle, but telling.

“He’s best off when he focuses on the specifics of his policies and the policy agenda, rather than trying to make some left revolution,” said Longabaugh, who parted ways with the candidate early last year. “The American public is not looking for a democratic socialist revolution.”

Public opinion polling backs up Sanders’ claim that voters, particularly Democrats, look favorably on his call for broad policy change. In exit polls from four states in last Tuesday’s primaries, a majority of voters supported a government healthcare plan instead of private insurance.

Peter Hart, a Democratic pollster, said that in his surveys, well over half of respondents support canceling student loan debt and Medicare for All, and a narrow majority said they would want a candidate who proposes large-scale plans, even if they cost more and may be harder to enact into law.

“We always think that these ideas are extreme, and yet within the Democratic Party electorate, there’s quite a bit of support for it,” Hart said.

With his consistent — some would say unyielding — stances, Sanders became the candidate of the Overton window, a concept developed by a conservative think tank official in the mid-1990s to describe how the boundaries of what is politically feasible can be moved.

But the downside to Sanders pushing the outer bounds of the policy discussion is alienating voters who only meet him partway.

“You’ve got to win to get anything done. If your goal is getting something done, then you’re failing,” Demissie said. “If your goal is to move the debate so that for the next Democratic president, the Overton window has shifted, maybe he’s been a success.”

In some cases, the rallying cries of Sanders’ campaigns have moved from rhetoric to reality in a piecemeal fashion — falling short of his maximalist posture.

On college affordability, for example, nearly 20 states now offer programs to cover the cost of tuition at community colleges or public four-year universities; many of those states introduced their plans after Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign.

The policies largely don’t go nearly as far as Sanders’ own proposal, which includes canceling all student debt in addition to erasing tuition fees.

“You start a program at one level, a modest level, and over time, you can increase and expand it,” said Ben Tulchin, who has worked as Sanders’ campaign pollster in both runs. “Rarely in politics do you pass the whole legislation all at once.”

That view of incremental progress stands in stark contrast to Sanders denouncing incrementalism. But Tulchin reconciled that contradiction by describing Sanders as a standard-bearer.

“He put the vision out there. He led on that effort,” Tulchin said. “People picked up on it and tried to make it happen.”

Sanders also had success in pushing the debate on the minimum wage. He aligned himself early with labor groups seeking a $15 per hour minimum wage, differentiating himself from 2016 rival Hillary Clinton, who backed a $12 hourly minimum wage.

Minimum wage has not been discussed much on the campaign trail this time around because there was near unanimity among candidates for increasing it to $15.

House Democrats approved legislation last year to raise the federal minimum wage to that level, but the Republican-held Senate has not acted upon it. In the private sector, major companies such as Amazon and Disney, facing heat from Sanders over wages, hiked their minimums in response to reach $15 an hour.

Sanders was hardly the first to embrace liberal policy positions; the run-up to his 2016 race saw a burst of progressive activism on economic inequality through the Occupy Wall Street movement, on wages by the Fight for 15 advocates and on criminal justice by Black Lives Matter activists.

“There has been this cycle of social movements and outside organizations really pushing the conversation,” said Evan Weber, political director and co-founder of the Sunrise Movement, a youth-oriented group that seeks an aggressive Green New Deal to combat climate change. “What’s unique about Sanders and his campaign is his responsiveness to the movement.”

Weber described a kind of symbiotic relationship between Sanders and the progressive grass roots, with the former elevating the policy priorities of the latter and inspiring new activism in response. He said he couldn’t imagine his group existing in its current fashion absent Sanders’ run in 2016.

“One of the things that really helped us believe that there was appetite for what the Sunrise Movement ended up becoming was seeing millions of young people who have never been involved in politics or a social movement before coming out of the woodwork for the Sanders campaign,” he said.

Because of the coronavirus, Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, even President Trump, have stopped rallies. Louisiana postponed its presidential primary.

Among the many issues hashed out in this year’s race, healthcare is the one on which Sanders has proven most influential.

“No candidate could escape this campaign without addressing ‘Medicare for all,’ whether they agreed with it or not,” said Jesse Ferguson, a Democratic strategist and former spokesman for Clinton’s 2016 campaign.

When Sanders introduced his Medicare for All bill in 2013, he had no Senate co-sponsors. Four years and one presidential campaign later, he introduced a version of the bill with 16 Senate co-sponsors, including four of his fellow presidential contenders.

But while the Vermont senator points to recent exit polling showing a majority of Democratic voters backing the proposal, even in conservative states like Mississippi, competing surveys show that support can drop significantly when concerns about cost or access to care are raised.

“Believe me, if you ask second, third and fourth follow-up questions, you begin to get a much more complicated picture,” Marshall said.

Ultimately, Sanders’ battle of ideas may have been eclipsed by Democrats’ views that a more pressing fight may be against Trump. Even though electability was seen as a dominant issue for voters throughout the campaign, Hart said that as recently as January, a healthy majority of voters also wanted a candidate proposing large-scale changes on healthcare, climate change and economic opportunity.

“There were competing ideas — do we want big change or do we want to defeat Donald Trump?” Hart said. “Obviously what we’ve seen over the course of the past three weeks is a huge movement to what’s most important is to defeat Donald Trump.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.